Employment, unemployment: India

(→Unemployment: among the various religious groups: 2009-10) |

(→‘Poor investment in agriculture behind rural job dip’) |

||

| Line 307: | Line 307: | ||

“Three decades ago, in 1983, about 34% of women in rural areas were working. This has steadily declined and now stands at just short of 25%. But the decline in the past two years is shocking – it is the most drastic decline we have ever seen,” she says. | “Three decades ago, in 1983, about 34% of women in rural areas were working. This has steadily declined and now stands at just short of 25%. But the decline in the past two years is shocking – it is the most drastic decline we have ever seen,” she says. | ||

| − | ===‘Poor investment in agriculture behind rural job dip’ | + | ===Low investment in agriculture === |

| + | ‘Poor investment in agriculture behind rural job dip’ | ||

Many argue that decline in women’s work is taking place because more women are now either studying or just staying home because the men of the family are earning enough. However,this is not supported by the data, according to Neetha. “Urban areas have more girls’ enrolment in schools and colleges, and better household incomes than rural areas. Yet women’s employment is increasing in urban areas and declining in rural areas,” she points out. | Many argue that decline in women’s work is taking place because more women are now either studying or just staying home because the men of the family are earning enough. However,this is not supported by the data, according to Neetha. “Urban areas have more girls’ enrolment in schools and colleges, and better household incomes than rural areas. Yet women’s employment is increasing in urban areas and declining in rural areas,” she points out. | ||

Revision as of 21:25, 6 August 2014

This is a collection of newspaper articles selected for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

2001-11: urban employment exceeds rural

For 1st time, urban areas pip villages in job creation

Subodh Varma TIMES INSIGHT GROUP

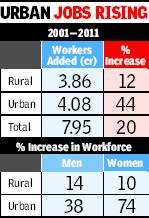

A fascinating, but worrying, picture of the way common Indians are earning their living emerges from recently released Census 2011 data. Urban areas have emerged as huge magnets for jobs, for the first time beating the rural hinterland in job creation in the past decade. Simultaneously, there is a rising dependence on short-term jobs, both in rural and urban areas, as regular full-term jobs fade away. The data also reveals huge differences in the kind of jobs men and women are getting. Clearly, India is going through a churning process, which will have far reaching effects on living standards, job related migration and gender relations.

More than half of the total 8 crore jobs created between 2001 and 2011 were located in urban areas, although the population staying in cities and towns is just a third of the total. This is a direct result of migration of people from unproductive farming in search of better prospects, supplemented by more areas getting defined as urban.

In the urban areas, women’s employment has seen a massive jump of over 74% since 2001, compared to just 38% for men. Women’s employment increased by over 1.2 crore in urban areas.

But the most significant feature is the creeping marginalization of jobs. Over 3 crore of the new jobs created in the past decade – 40% of the total – have been designated as ‘marginal’. This means that people work in these jobs for less than six months. A quarter of India’s 40-crore workforce is now subsisting on such marginal work.

While cultivation as the main occupation has declined by about 8% over the past decade, among marginal workers the picture is totally different. It has increased by 35% among male marginal workers, but declined by 20% among women. Seen in the context of the huge decline in main cultivators, it appears that men have been forced to work part time in their fields and part time either in others’ as agricultural labour or even in other kinds of work.

There appears to be a distinct shift towards what the census still persists in calling ‘other’ work – industry and services. And the vast bulk of these jobs are being created in cities and towns. Main workers in ‘other’ work jumped by 38% over the past decade compared to a measly 10% increase in rural areas. This is not surprising as most industries and service related jobs are located in urban or periurban areas (areas adjoining urban areas). Even here, the share of short- term workers in these ‘other’ jobs increased by a jaw dropping 84%.

2004-2010: Jobless growth?

‘Jobless growth’ during UPA-1, admits Centre

Self-Employed Dropped From 56.4% To 50.7% Of Workforce

Rajeev Deshpande TNN

New Delhi: Some 20 months after hotly contesting data on UPA-1’s “jobless growth”, the government has admitted to lack of substantial increase in employment between 2004-05 and 2009-2010, with the selfemployed workforce shrinking from 56.4% to 50.7% of the total workforce.

In absolute numbers, the self-employed decreased from 258.4 million to 232.7 million in this period while regular salaried workers rose from 69.7 million to 75.1 million. The ranks of casual labour rose from 129.7 million to 151.3 million. In all, the total workforce increased from 457.8 million to 459.1 million, a rise of just 0.3% over this period.

The ministry of planning has identified limited flexibility in “managing” the workforce, high cost of complying with labour regulations, poor skill development and a vast unorganized sector as reasons for dissatisfactory growth in employment.

Responding to Parliament’s finance standing committee’s query on why India was not creating enough productive jobs, the ministry said while the number of salaried employees increased, the selfemployed segment declined.

Interestingly, the ministry referred to the same 66th round of the National Sample Survey Organization that irked the government in June 2011 with Planning Commission deputy chairperson Montek Singh Ahluwalia slamming the report as inaccurate.

The controversy deeply embarrassed the ruling coalition as the data seemed to negate the Manmohan Singh government’s “inclusive growth” slogan despite policy initiatives intended to make growth less uneven.

Under official pressure, the NSSO later put down the employment statistics to factors like rising incomes resulting in women choosing to stay at home instead of taking up physically challenging jobs.

Yet , the planning ministry that has told the finance committee “India had an average growth rate of 7.9% in the 11th plan. However, this growth did not lead to increase in employment opportunities”.

Stating that the NSSO data exhibited a shift in employment status, the ministry said in the period 2004-05 to 2009-10, the percentage of regular salaried workers increased from 15.2% to 16.4% and there was a jump in casual labour from 28.3% to 33%. It indicates that informal employment that accompanies new real estate development, industry and urbanization has lagged.

This would include service providers like road side eateries, local transport, small shops and services like appliance repair.

The planning ministry did not explain the jump in casual labour but this could due to the rural employment guarantee scheme, although the government has also argued that the trend contradicts claims of slow employment.

The numbers may look even less flattering when the next bunch of statistics is available in view of the plummeting growth.

The government has listed measures like boosting manufacturing, developing skills, promoting labour intensive sectors and simplifying labour laws as an antidote to the employment logjam.

GOING SLOW

Percentage of self-employed dropped from 56.4% of total workforce in 2004-05 to 50.7% in 2009-10

Percentage of regular employees rose from 15.2 to 16.4 and of casual labourers from 28.3 to 33

In absolute numbers, number of self-employed was 258.4m in 2004-05 and 232.7m in 2009-10

There were 69.7m regular workers in 2004-05 and 75.1m in 2009-10

Casual labourers rose from 129.7m to 151.3m

Total workforce rose from 457.8m in 2004-05 to 459.1m in 2009-10, an increase of just 0.3% Casual labour grew from 28% to 33%

Job creation and the states

Poorer states take the lead in creating jobs

Subodh Varma | TIMES INSIGHT GROUP 2013/06/17

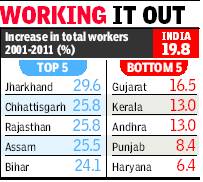

Most of the poorer, less industrialized states like Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh and Bihar appear to have done well in increasing their work force in the past decade according to recently released Census 2011 data. Surprisingly, richer or more urbanized states like Punjab, Haryana and Kerala have lagged far behind in job creation. But if you take away natural population growth, the picture changes dramatically.

It becomes clear that the workforce increase in the poorer states is mainly because of their higher than national aver- population growth. But again surprisingly, the richer states still remain at the bottom of job creation rankings. In terms of increase in total workers’ population, the top five states were Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, Rajasthan, Assam and Bihar, counting only major states, that is, those with over 2 crore population. The increase in their respective workforce was considerably higher than the national average. The states with the least increase over the past decade were Haryana, Punjab, Andhra Pradesh, Kerala and Gujarat.

UP, Bihar: least job creation

Since there is a natural growth in population, these figures do not give a correct picture of the changes in job opportunities in these states. Arough idea of what is the actual change in employment can be had by deducting the growth in population from the growth in workers. This reveals that Orissa, Assam, Kerala, Jharkhand and Rajasthan are the top five states in terms of job creation during 2001 and 2011.

While Orissa, Assam and Kerala appear to benefit from a much reduced population growth rate, Jharkhand and Rajasthan seem to have genuinely boosted jobs creation. After adjusting for population growth, the states with least job creation were Haryana, Punjab, Gujarat, Bihar and Uttar Pradesh. The latter two were hamstrung by still high population growth rates but the other three are laggards in job creation, reflecting stagnation and increased mechanization. These three also showed an absolute decline in the female workforce over 2001 and 2011. Census counts short term workers – those doing less than six months' work in a year – separately.

A look at how the cookie crumbles across the states in terms of short term work and longer term, more regular work throws up some bizarre results. While Maharashtra, Assam, Karnataka, Rajasthan and Gujarat created the most long term workers (‘main workers’), Bihar, Jharkhand, Punjab, West Bengal and Orissa added the least. On the other hand, short term, marginal workers increased by a jaw dropping 93% in Bihar, followed by Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, Orissa, UP. This is the fragile nature of job growth in states which may appear to be adding jobs in the past decade.

The rural-urban divide is starkly shown up in job creation, reflecting the doldrums that Indian agriculture is in. Across India, rural job growth was just 13% compared to 44% in urban areas. Some of the most agriculturally advanced states like Haryana and Punjab showed a decline in rural workforce while others like Andhra Pradesh and Gujarat had very small increases. The situation flips for urban areas where most states showed a healthy increase in the workforce. But Punjab, along with the two most urbanized states in the country, Tamil Nadu and Maharashtra, still remained at the bottom.

Unemployment, wages, NREGS

Joblessness on rise

Non-NREGS work paying more: Govt survey

TIMES INSIGHT GROUP

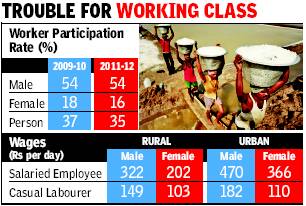

Between 2009-2010 and 2011-2012, the proportion of people working slipped slightly in India, and the share of unemployed persons ticked up, a government report released on Thursday revealed. In 2009-10, 36.5% of the population was gainfully employed for the better part of the year. By 2011-12, the proportion of such workers had dipped to 35.4%. Meanwhile, the unemployment rate went up from 2.5% to 2.7%.

These findings form the crux of a survey on employment and unemployment carried out by the National Sample Survey Organization (NSSO). The survey covered over one lakh households and was carried out between July 2011 and June 2012. The pan-India figures hide a deepening chasm between job opportunities for men and women. While the share of employed men remained roughly constant between 2009 and 2011, women’s employment dropped from 18% to 16%.

Loss of jobs

This may appear a small decline but translated into real numbers the crisis in employment is starkly revealed. In rural areas, about 90 lakh women lost their jobs in the two-year period. This would have been catastrophic but for the fact that in urban areas about 35 lakh women were added to the workforce.

Men joined the workforce in both urban and rural areas, though they got many more opportunities in towns and cities than in villages. Men’s participation in the workforce jumped from 99 million to 108 million in urban areas and from 228 million to 231 million in rural areas.

Unemployment

Kerala had the highest unemployment rate of close to 10% among the larger states. West Bengal (4.5%) and Assam (4.3%) were other large states with relatively high unemployment rates. Among smaller states, Nagaland had a staggering jobless rate of 27%, but this may be compromised data as surveys are difficult in strife-torn areas. Tripura too had a high unemployment rate of over 15%.

Wages

The report also contains striking information on daily wages of casual labourers and regular or salaried employees. In the government’s jobs scheme (MGNREGS), male workers were getting an average of Rs 112.46 per day, while in non-MGNREGS public works the rate was Rs 127.39, and in non-public works it was Rs 149.32. For women, the averages were more similar at about Rs 102 to Rs 110, though lower than men for the same work. This appears to go against a widely held belief that MGNREGS rates are setting the standard for all other wages in rural areas.

The wide gulf in urban and rural wage rates explains why people are migrating to live in cities. A male casual labourer earned about Rs 150 per day in rural areas, but his urban counterpart got Rs 180 per day. Similarly, a salaried employee could earn about Rs 300 per day in rural areas but in urban areas the same would shoot up to nearly Rs 450.

Unemployment among religious groups

2009-10

Urban Sikhs face highest unemployment

Mahendra Singh TNN

The Times of India 2013/07/29

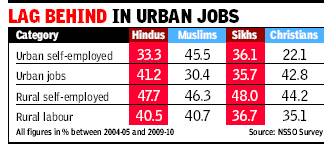

Unemployment was highest among Sikhs living in cities and towns during 2009-10 while the rate of joblessness showed a downward trend for Muslims in both urban and rural areas, a government survey released this month has revealed.

Muslims had the lowest per capita spending, according to the National Sample Survey Organization (NSSO), which in its 2009-10 survey put out a new report on employment trends for religious groups.

Unemployment

Among communities, unemployment increased only among Sikhs living in urban India. The community saw unemployment rise from 4.6% in 2004-05 to 6.1% in 2009-10. However, among rural Sikhs, the rate declined sharply from 3.5% to 2.4% during the period.

The high unemployment rate among Sikhs in urban areas may be attributed to the fact that they are more educated and work with their hands and are vulnerable to economic slowdown which hit India in 2009-10, the period of survey.

In rural areas, unemployment was highest among Christians at 3.9%. However, it declined from 4.4% in 2004-05. The steepest decline in urban areas was witnessed among Christians, with the unemployment rate falling by 5.7 percentage points from 8.6% in 2004-05 to 2.9% in 2009-10.

Hindus had a stable unemployment rate at 1.5% in rural areas during the fiveyear period while all other communities in villages saw a decline. In urban India, the rate fell from 4.4% to 3.4% among Hindus.

Unemployment among Muslims in both rural and urban areas is falling. The rate declined from 2.3% in 2004-05 to1.9% in 2009-10 among Muslims living in villages. In cities and towns, the unemployment rate among Muslims fell from 4.1% to 3.2% during the five-year period. However, most Muslims in both rural and urban areas are self employed.

Spending/ consumption expenditure

Per capita spending was highest for Sikhs, followed by Christians and Hindus.

At the all-India level, the average monthly per capita consumption expenditure (MPCE) of Sikh households was Rs 1659, followed by Christians (Rs 1543), Hindus (Rs 1125) and Muslims (Rs 980).

The survey found that self-employment was the mainstay for all religious groups in rural areas. The major source of earning from self-employment in agriculture was the highest among Sikhs (about 36%), but Muslims topped the chart in the category of rural workers.

In urban India, the proportion of households with major source of earning as self-employment was highest for Muslims (46%). The major source of earning from regular wage/salaries was the highest for Christian households (43%).

Most people irrespective of religious affiliation own between 0.1 and 1 hectare of land. About 43% of Christian households, 38% of Muslim and 37% of Hindu cultivated more than or equal to 0.001 hectare of land but less than 1 hectare. The proportion of households cultivating more than 4 hectares of land was the highest for Sikhs (6%), followed by Hindus (3%).

Rural wages, poverty, nutrition

2011-12: Rural wages, nutrition rise

Poverty declines

Rising rural wage may boost UPA’s chances

Swaminathan S Anklesaria Aiyar

The Times of India 2013/07/07

For all the current gloom about the economy, the 2011-12 data on employment and consumption shows a remarkable one-third increase in average household consumption over two years, well above the rate of inflation.

Four trends stand out. First, poverty is falling sharply. Second, wages are rising impressively. Third, people are shifting from cereals to superior foods. Fourth, contrary to popular perception, the employment guarantee scheme (MNREGA) has not been the key driver of higher wages.

Poverty ratio

The government has not yet provided a firm figure for the poverty ratio in 2011-12 compared with the last survey in 2009-10. But estimates from limited data suggest that the poverty ratio has fallen from 29.8% to just 24-26%. Earlier, poverty was falling by 0.75 % per year. This may have accelerated to 2% per year.

Wages

The most comprehensive consumption measure shows rural monthly spending per capita up from Rs 1,053 to Rs 1,430. For rural casual labour, other than in public works, male wages rose from Rs 102 to Rs 149, and female wages from Rs 69 to Rs 102. Urban trends were similar. Remarkably, casual wages grew faster than average national consumption: the poor fared disproportionately well. However, female wages grew more slowly than male wages.

Surprisingly, higher wages did not attract more people into the workforce. Over the two years, the male rural workforce increased by only 2.7 million, while the female rural workforce actually declined by 2.7 million. The unemployment rate rose slightly from 2.0% to 2.2%, but both rates are very low. The biggest problem is not lack of jobs but lack of workers. The optimistic explanation is that millions of youngsters have chosen to study instead of working. The pessimistic explanation is that women find work conditions unsafe or unsuitable.

Are machines causing unemployment?

Some analysts fear that rural women are being displaced by growing mechanization. Punjab farmers are switching to mechanical rice transplanters, and combine harvesters are spreading even in Bihar. But rural wages are rising sharply, contradicting the theory that machines are causing unemployment. Rather, the scarcity of labour is forcing farmers to mechanize. We need more research to explain the abysmally low participation of women in the workforce, down from almost 30% in 2004 to just 22% today.

Female participation

In urban areas, female participation is a pathetic 15%. For this to happen at a time of sharply rising wages — which should normally attract more women to work — is a huge unsolved puzzle. MNREGA is targeted at women, yet rural female participation has plummeted.

Food consumption patterns

Food consumption patterns have been changing dramatically. Between 1993-94 and 2011-12, the share of cereals in consumption halved from 24.2% to 12% in rural areas, and from 14% to 7.3% in urban areas. The share of non-food items shot up from 36.8% to 51.4% in rural areas, showing growing prosperity. Rural folk have shifted to superior foods. What’s up is the share of beverages, eggs, fish, meat, fruit and nuts.

Clearly, Indians as a whole have more than enough cereals and are moving to superior foods and consumer durables and services. The shift is evident in all income groups. The Food Security Bill aims to expand subsidized cereal supply from 40% of the population to 67%. Clearly this is a middle-class giveaway, unrelated to food security.

In 2004, only 2% of Indians said they were hungry any time of year. These are the people needing food security, not the middle-class. However, while hunger is limited, malnutrition is widespread. People need additional iron, vitamins and proteins. But the Food Security Bill targets only cereals.

MNREGA

In its initial years, MNREGA typically paid higher wages than the minimum wage. Indeed, many states raised their minimum wage rate sharply on finding that the Centre would foot the MNREGA bill.

Earlier, when states raised the minimum wage for political reasons, market rates did not move at all. Farmers dismissed the minimum wage as a gimmick. But today, market rates for casual labour have risen well above MNREGA rates. In 2011-12, MNREGA paid on average Rs 112 to males and Rs 102 to females. This was well below the open market rural wage of Rs 149 per days for males, and marginally below the rate of Rs 103 for females. The main reason seems to be fast GDP growth for a decade. All Asian miracle economies achieved rising wages through fast GDP growth, not employment schemes. India seems no different.

Employment among Muslims

Number of jobless Muslims dips in both villages & cities

But Majority Still Outside Organized Sector

Mahendra Singh TNN

The Times of India 2013/08/19

New Delhi: Unemployment among Muslims is going down, marking an encouraging trend to gladden the champions of inclusive growth.

The unemployment rate for the community declined from 2.3% in 2004-05 to 1.9% in 2009-10 in rural areas and from 4.1% to 3.2% in urban areas. However, a vast majority of Muslims in both rural and urban areas are not part of the organized workforce compared to other religious groups.

In contrast, Hindus had a stable unemployment rate of 1.5% in rural areas during the five-year period while it fell from 4.4% to 3.4% in urban India.

According to data released by the National Sample Survey Organization, Muslims are mainly engaged in self-employment and as rural labour.

In cities and towns, Muslims are at the bottom of the ladder in the ‘regular wage/ salaried’ category. Among the major religious groups, only 30.4% of Muslim households are in regular jobs, followed by Sikhs (35.7%), Hindus (41%) and Christians (43%). In contrast, the proportion of households with major source of earning as self-employment was the highest for Muslims (46%) in urban areas.

In villages, Muslims (41%) are the largest group employed as rural labour with another 46.3% in the self-employed category. Majority of households of all religious groups, other than Muslims, belong to the self-employed in agriculture category, the survey found.

In rural areas, the proportion of households depending on self-employment was the highest among Sikhs (48%). The community’s major source of earning is self-employment in agriculture (around 36%), followed by Hindus (33%) and Christians (30%).

Intake of Muslims in central government organizations has increased by more than 3 percentage points in six years, from 6.93% in 2006-07 to 10.18% in 2010-11. This coincides with directives by the Centre to ministries and departments that they should take special measures to boost minority presence in jobs. That more Muslims are joining paramilitary forces and railways could start a robust trend. Increasing presence in the police would also strengthen their confidence in security matters.

Muslim share in govt jobs moving upwards

Subodh Ghildiyal TNN

The Times of India 2013/08/19

New Delhi: The intake of Muslims in central government bodies has increased by over 3 percentage points in six years, reflecting a visible improvement in the community’s share of public sector jobs that the UPA marked out as priority after coming to power in 2004.

Government figures show that the recruitment of minorities in central government organizations stood at 10.18% in 2010-11, up from 6.93% in 2006-07.

The increase of three percentage points in employment across sectors in the last six years coincides with the directives that the Centre issued to ministries and departments that they should take special measures — publicity campaigns about recruitment drives and inclusion of minority members in interview panels — to boost minority presence in jobs.

Minority has been a thinly-disguised term for Muslims who form an overwhelming share of religious minorities. Social activist and former National Advisory Council member Harsh Mander dubbed the increase as significant and credited the community for the success.

“It is the outcome of efforts on the part of community members to break out of restraints on social mobility they have been traditionally bound by,” he said, adding the government contribution in the trend was smaller.

The percentage of minorities in total hiring across central government jobs was 6.93% in 2006-07. It went up to 8.23%, 9.90%, 7.28% and 10.18% in the following years. Sensing inconsistency, the ministry has called for review of the 2011-12 figures that stand at a dismal 6.24%.

The significance of increasing number of Muslims in central recruitment extends beyond mere job share.

That they are joining paramilitary forces and railways, the largest public sector employers, in greater numbers could start a robust trend for future. The community’s increasing share in the police force would also strengthen their confidence in security matters.

‘Muslims lag in per capita spend’

Around 25% of Muslims are engaged in self-employment in non-agricultural sector, followed by Christians (14.7%), Hindus (14.5%) and Sikhs (12.4%), according to the NSSO data.

The poor state of affairs among Muslims is also reflected in low per capita spending compared to other religious groups. The household monthly per capita consumer expenditure (MPCE), which serves as a proxy for income and is usually taken to reflect the living standard of a family, was lowest among Muslims. Muslim households were spending Rs 980 (Rs 1,272 in urban areas and Rs 833 in rural areas).

The average MPCE (for both urban and rural) was the highest for Sikh households, followed by Christians and Hindus. The average MPCE of a Sikh household was Rs 1,659 (Rs 2,180 in urban areas and Rs 1,498 in rural areas).

Employment in North East India

Job scenario in most NE states alarming

More Workers Join Labour Force Than Jobs Are Created In Mizoram, Meghalaya, Arunachal

Subodh Varma TIMES INSIGHT GROUP

Made up of eight states and accounting for about 4% of India’s population, the northeast is better known for its separatist movements and incendiary ethnic conflicts. It has 25 Lok Sabha members, 14 of them from Assam, and so, does not draw serious attention from political parties involved in the national sweepstakes. The region receives huge funds from the central government that prop up the local economies. But simmering under the surface is a question that haunts everybody — what about jobs?

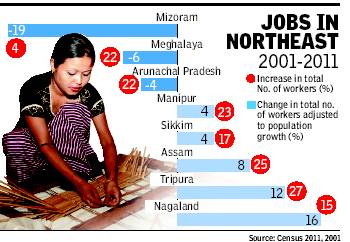

Census 2011 data released this year has some strange and disturbing trends on jobs in the northeast. If states were to be ranked by growth in jobs between 2001 and 2011, Tripura and Assam would figure among the top five states with 27% and 26% increases in total number of workers, respectively. But on the flip side, the growth in workers was just 4% in a decade in Mizoram – the lowest among all states. Three states — Mizoram, Nagaland and Sikkim — were below the national average of 20% growth in workers between the two censuses.

These growth rates may be deceptive because population has been growing in the same period. A better idea of how many jobs are being created can be had by deducting population growth rate from the increase in workers. This reveals a much more serious situation in the northeast.

Three states — Meghalaya, Mizoram and Arunachal Pradesh — show a decline in total workers. This means that more workers are joining the labour force than jobs are being created. Among these, Mizoram is facing a shocking crisis with a decline of over 19%. One factor could be that Mizoram is now an urbanmajority state – over 52% of its population stays in urban areas. So the buffer of agriculture is absent. Seen in the context of the fact that Mizoram has one of the highest literacy rates at 91%, this must be food for thought for policy makers both in Aizawl and New Delhi.

In two other states, Sikkim and Manipur, the adjusted growth rate plummets down to around just 4% in a decade. Tripura with 12% and Assam with over 8% perform creditably in comparison to the other states. Nagaland has the most bizarre situation – since the total population of the state has declined between 2001 and 2011 the two censuses, it shows a rise of nearly 15% in its workforce, adjusted to population.

Lack of growth in non-farm employment in most states, and the difficult hilly terrain, about 70% of which is under forest cover, are two key reasons why employment is stagnating in the northeast, says Bhupen Sarmah, director of the O K Das Institute, a Guwahati-based research institute. “It is an illusion to think that development will take place merely on the basis of injection of funds from the central government. The northeast receives a huge amount of this largesse but look what is the result,” Sarmah points out.

Sarmah may have a point, although it is also true that a lot of the largesse remains on paper. According to the ministry of development of north eastern region, a special non-lapsable fund created for financing projects in the northeast approved projects worth Rs 12,716 crore between 1998 and 2012. Sounds great, but there’s a catch — only about Rs 9,231 crore were actually released and state governments submitted utilization certificates for only Rs 5,641 crore. A Lok Sabha question recently revealed that about Rs 2,000 crore remains unspent from this fund every year between 2008-09 and 2010-11.

Another example is the national job guarantee scheme (MGNREGS) that promises 100 days of employment to anybody who demands. In some states it has become a mainstay of economic support, like in Mizoram with average 73 days of work provided and Tripura (87 days). The national average is just 44 days per household.

But some other states in the northeastern region are drastically lagging — Assam (25 days), Nagaland (35) and Manipur (37).

The employment of women: 2009-12

Rural women lost 9.1m jobs in 2 yrs, urban gained 3.5m

Not Getting Long-Term Work: Survey

Subodh Varma TIMES INSIGHT GROUP

Women’s employment has taken an alarming dip in rural areas in the past two years, a government survey has revealed. In jobs that are done for ‘the major part of the year’, a staggering 9.1 million jobs were lost by rural women. In urban areas, the situation was quite the reverse, with over 3.5 million women added to the workforce.

This emerges from comparing employment data of two consecutive surveys conducted by the National Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO) in 2009-10 and 2011-12. Key results of the later survey were released last month. Both rounds had a large sample size of nearly 4.5 lakh people.

“The survey shows that in the continuing employment crunch in rural areas, the most vulnerable sections — like the women — are getting eliminated,” says Amitabh Kundu, professor of economics at Jawaharlal Nehru University.

If subsidiary work, that is short-term, supplementary work is also counted, women’s employment numbers improve, but they still show a huge decline of 2.7 million in two years. This is a reflection of the fact that women are no longer getting longer-term, or principal, and better paying jobs, and so are forced to take up short-term transient work.

Declining women’s employment in rural areas is a long-term trend in India despite high economic “growth”, says Neetha N of the Centre for Women’s Development Studies.

“Three decades ago, in 1983, about 34% of women in rural areas were working. This has steadily declined and now stands at just short of 25%. But the decline in the past two years is shocking – it is the most drastic decline we have ever seen,” she says.

Low investment in agriculture

‘Poor investment in agriculture behind rural job dip’

Many argue that decline in women’s work is taking place because more women are now either studying or just staying home because the men of the family are earning enough. However,this is not supported by the data, according to Neetha. “Urban areas have more girls’ enrolment in schools and colleges, and better household incomes than rural areas. Yet women’s employment is increasing in urban areas and declining in rural areas,” she points out.

But what is the reason behind this jobs crisis in rural India? “A decline in public investment in agriculture, and in extension work for dissemination of knowledge coupled with increasing mechanization are the main causes of this crisis of jobs,” says V K Ramachandran, professor of economic analysis at the Indian Statistical Institute, Bangalore. He also blames the severe slowdown in expansion of irrigation and supply of electricity to rural areas for causing jobs to dry up.

Satya Narain Singh, deputy director general of NSSO, told TOI that there were no issues of measurement or sample size in the surveys. He pointed out that the population for 2010 was based on Census projections while that for 2012 was based on actual Census 2011 data. This could introduce a small over-estimation of the 2010 population. But the “decline in female workforce is in line with the trend of decline observed in recent decades”, Singh said.