Employment, unemployment: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

A: EMPLOYMENT/ UNEMPLOYMENT STATISTICS

Employment creation

Employment trends

1983- 2022

From: Surjit S Bhalla & Tirthatanmoy Das, March 20, 2023: The Times of India

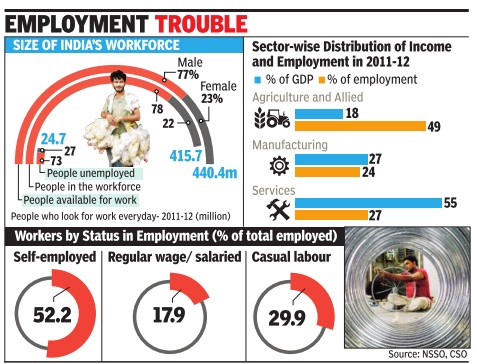

See graphic:

Employment trends in India, 1983- 2022

The State of Working India 2023

Sep 25, 2023: The Times of India

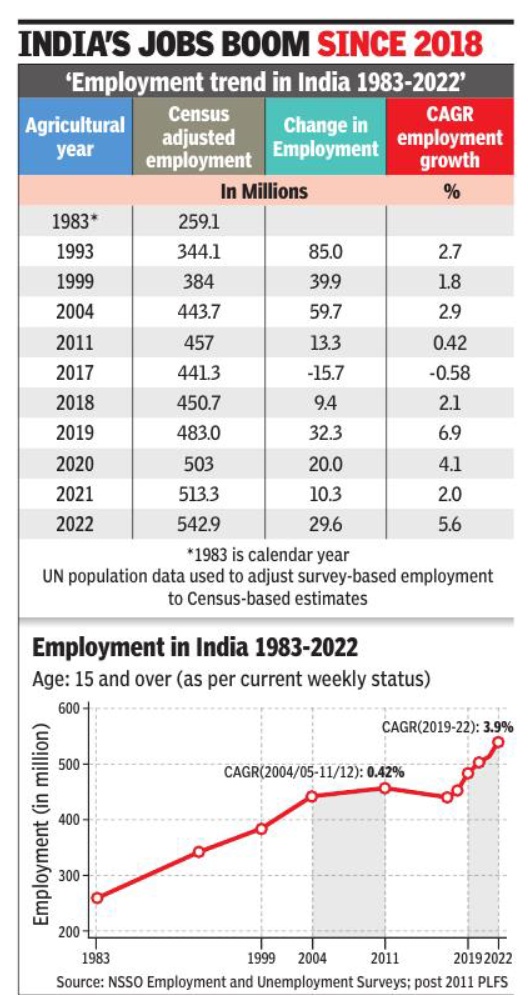

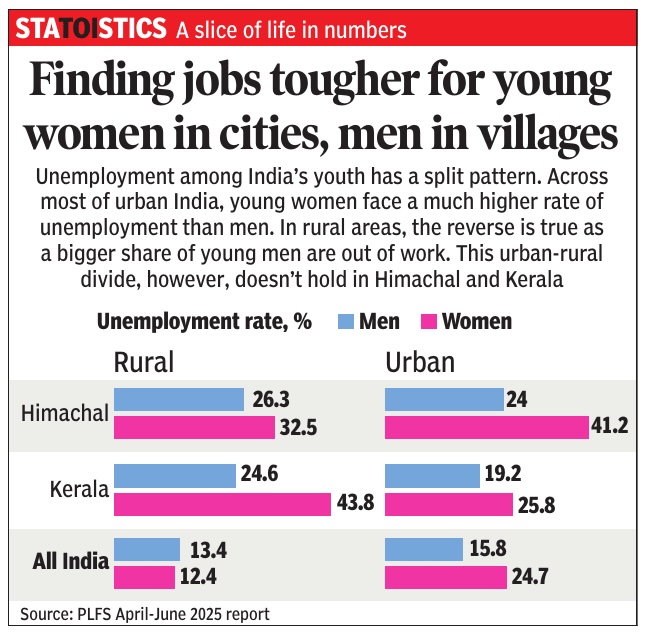

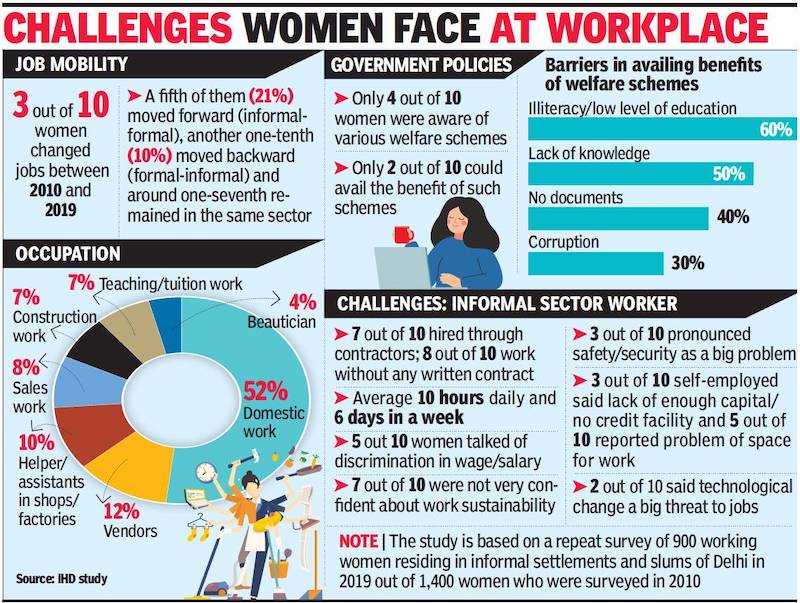

India’s bounce-back from the pandemic’s economic fallout was fast and sharp. In 2021-22, not only had the GDP of ₹149.25 lakh crore risen 9.1% over the previous year, it had also surpassed the preCovid level. Employment however has been a different story. Azim Premji University’s State of Working India 2023 draws together employment-related data from different GOI reports to show that the resilience of the job market, particularly for women and young graduates, has lagged that of the overall economy.

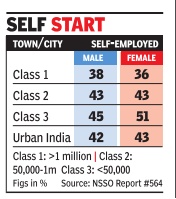

On the surface, one of the highlights of the employment data has been a sharp rise in both men and women working in the post-Covid phase and a simultaneous decline in the unemployment rate. The unemployment rate in 2021-22 was 6.6%, over two percentage points lower than the same in 2019-20. The upward trend in women’s employment has been notable. However, a fine-grained analysis by SWI 2023 report showed that there’s been a structural deterioration in the nature of women’s employment. The jump in women’s employment has been driven by self-employment, particularly in the category of unpaid work. Self-employment is generally a fallback option, which suggests that the job market for women may have worsened.

This is corroborated by the inflation-adjusted monthly earnings of the self-employed over the last five years. For sure, the monthly earnings are higher than both 2019-20 and 2020-21. But the monthly earnings of ₹12,089 in 2021-22 was lower by 2% than the same in 2017-18, the year GOI began to present annual employment data. There’s economic stress underlying the increase in women’s participation in the labour force. Little surprise then that political parties are rushing to tailor fiscal policies to provide monthly income support to women in different states. Youth unemployment has long been an area of concern. SWI showed that unemployment for highly educated job seekers (graduates and above) was over 20% till the age of 29. Subsequently, it collapses fast which does raise questions about the quality of jobs.

For decades, India’s structural transformation in the job market has lagged the growth in GDP. The term ‘jobless growth’ is shorthand for the lack of correlation between growth of GDP and employment. This phenomenon appears to have worsened for women in the post-Covid phase. It’s something that deserves more attention as the contribution of women is critical if India wants to be a developed economy.

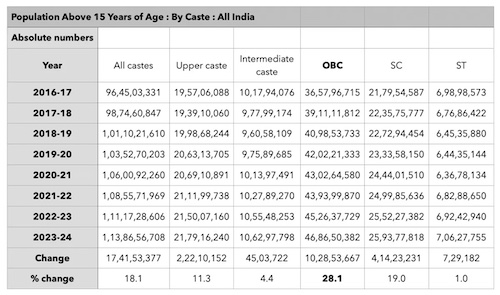

Caste and employment

Udit Misra, Oct 5, 2023: The Indian Express

From: Udit Misra, Oct 5, 2023: The Indian Express

From: Udit Misra, Oct 5, 2023: The Indian Express

From: Udit Misra, Oct 5, 2023: The Indian Express

From: Udit Misra, Oct 5, 2023: The Indian Express

From: Udit Misra, Oct 5, 2023: The Indian Express

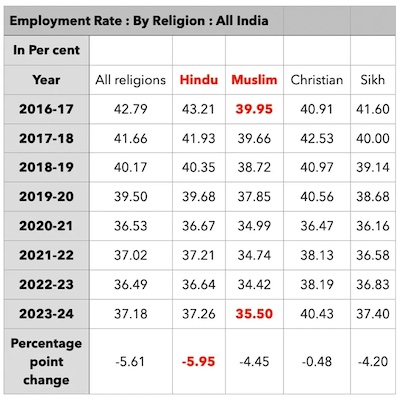

Some Basics on Employment Metrics

There are three variables that one needs to look at when talking about employment in India.

One is the Labour Force Participation Rate (LFPR). Simply put, it gives a sense of how many Indians are “demanding” a job.

The “Labour Force” consists of persons who are of 15 years of age or more and are either of the following two categories:

1. are employed

2. are unemployed and are willing to work and are actively looking for a job

The LFPR is expressed as a percentage of the working-age population.

The second variable is Unemployment Rate (UER). It is nothing but the number of people in the labour force who are looking for a job but as yet unemployed. The UER is expressed as a percentage of the labour force.

Don't miss | Why everyone’s counting on the Census — and why a delay hurts

In everyday parlance, the unemployment rate often dominates the general public discourse. However, in India’s case, the UER often underestimates the joblessness because the LFPR itself keeps falling.

Simply put, it has been found that if they do not get a job over time, a lot of unemployed people get discouraged and leave the labour force (that is, stop actively looking for a job). With unemployed people leaving the labour force, the ratio of unemployed to total labour force falls. As such, often in India, the UER falls not because more people have got jobs but because the LFPR itself falls (that is, when more people — who failed to get a job — stop looking for a job altogether).

As such, the best metric to look at is Employment Rate (ER). The ER dispenses with the labour force calculation and simply looks at the total number of people employed as a percentage of the working-age population. By not basing itself on LFPR, the ER avoids the problem of a falling LFPR artificially dragging the unemployment rate.

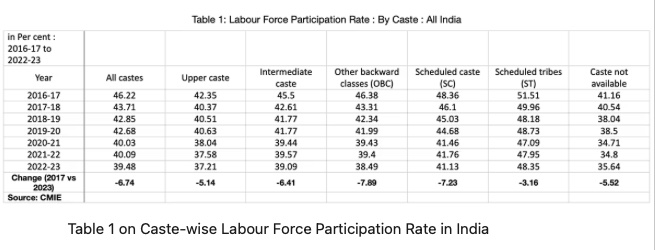

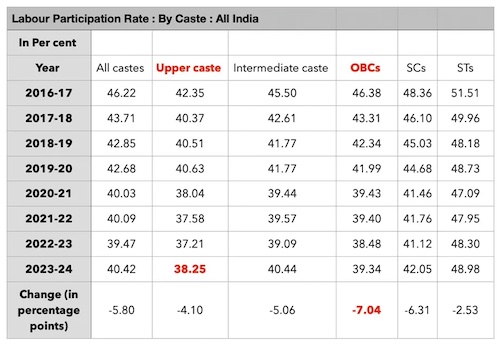

Caste-wise LFPR

Table 1 gives the details of caste-wise LFPR since the start of the 2016 financial year. Apart from the well-known groupings, the intermediate castes grouping refers to castes such as Marathas, Jats, Gujjars, and others who often aspire to be included in the OBC category.

Table 1 on Caste-wise Labour Force Participation Rate in India

The data shows some very clear trends.

One, LFPR has fallen for each caste. If one ignores the data for the category for which caste was not available, then the LFPR of the so-called upper castes is the lowest among all other castes; it is 37.21%. In other words, the demand for jobs is the lowest among the upper castes.

Two, the biggest fall in LFPR since 2016, however, has been among OBCs and SCs. In other words, people belonging to these two caste groupings have been the worst affected by the negative trend of India’s LFPR.

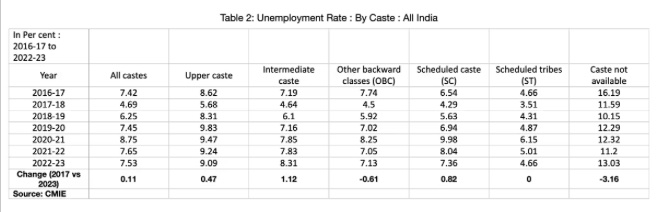

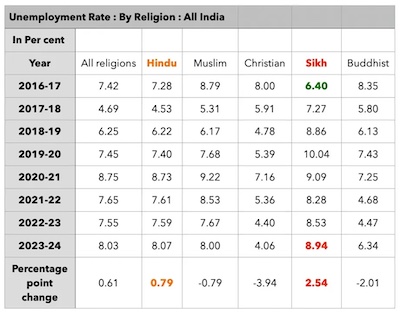

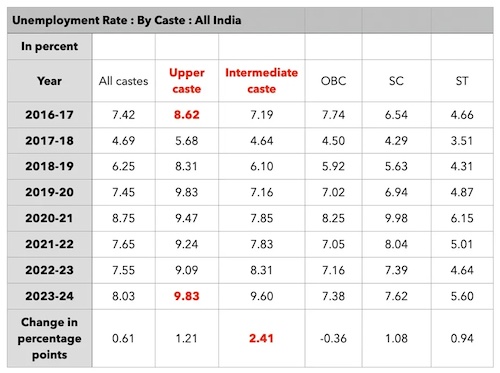

Caste-wise Unemployment Rate

Table 2 shows the UER for each caste group.

The UER has remained persistently high for India. Moreover, notwithstanding India’s economic recovery, it was higher in the last financial year (2022-23) than six years ago.

Table 2 on Caste-wise Unemployment Rate in India

This is true for all caste groups barring the OBCs, for whom the unemployment rate has fallen marginally. That UERs are higher despite LFPRs falling points to the more worrying trend — that UER is higher even when the proportion of people demanding a job has come down.

As far as the fall in the UER for OBCs is concerned, it has happened as the LFPR for them has witnessed the biggest fall among all caste groups.

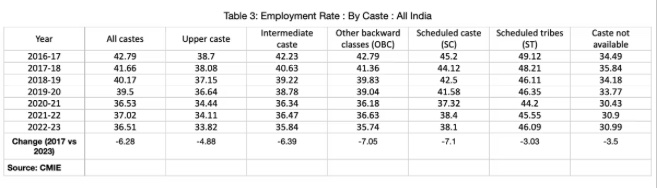

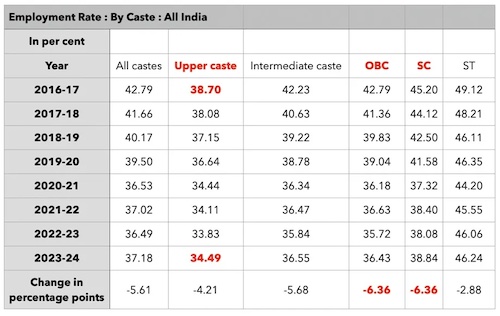

Caste-wise Employment rate

TABLE 3 best captures the combined reality of falling LFPR and high UER for each caste category. This table provides the Employment Rate and as the table shows, the ER has fallen for each and every caste group.

Table 3 on Caste-wise Employment Rate in India

In other words, the proportion of people belonging to a particular caste in the working-age population who are employed has been coming down for every caste.

Again, while the upper castes have the lowest employment rate, the biggest drop in ER has been witnessed among OBCs and SCs.

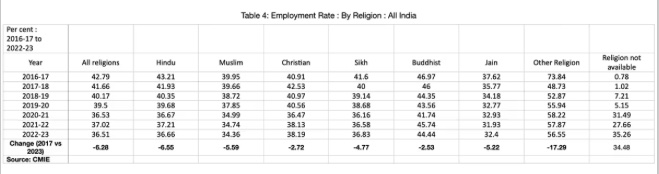

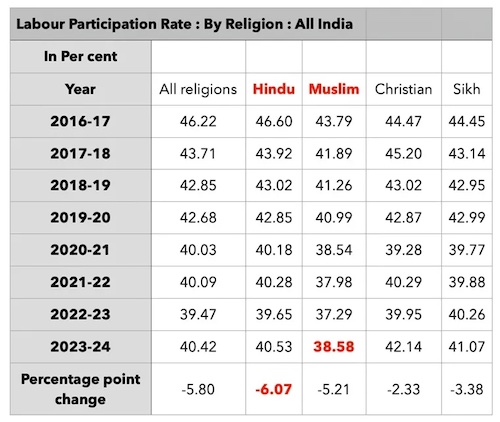

Religion-wise Employment rate

Reportedly, the Bihar caste survey looked at caste across religious identities as well. In other words, it categorised non-Hindus (such as Muslims) into different castes.

As such, it might be relevant here to look at the religion-wise employment rates as well.

Table 4 on Religion-wise Employment Rate in India

Table 4 throws up a very interesting result: Among the main recognised religions, it is the Hindus who have suffered the biggest fall in employment rate between 2016-17 and 2022-23 even as the Jains have the lowest employment rate.

Caste-wise consumer sentiments

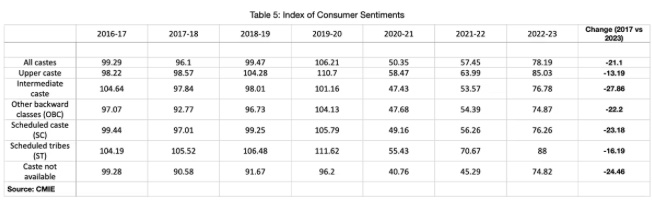

Table 5 maps the absolute levels of CMIE’s index of consumer sentiments for each caste. According to CMIE, the main aim of the Consumer Sentiments Index is to measure perceptions and expectations accurately so that the business community can understand the mood of the consumer and anticipate changes in the same.

Table 5 on Index of Consumer Sentiments in India

For one, the data shows that the consumer sentiments for almost all caste groups are 20% to 25% below their 2016-17 levels. The lowest levels of consumer sentiment were for the OBCs. However, the worst affected were the intermediate castes — the castes who aspire to be included in the OBC category.

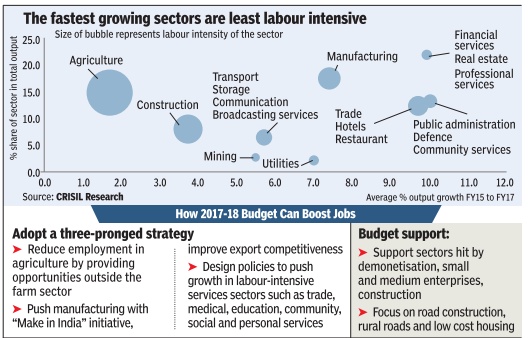

The main sectors

The Times of India, Sep 11 2016

Subodh Varma

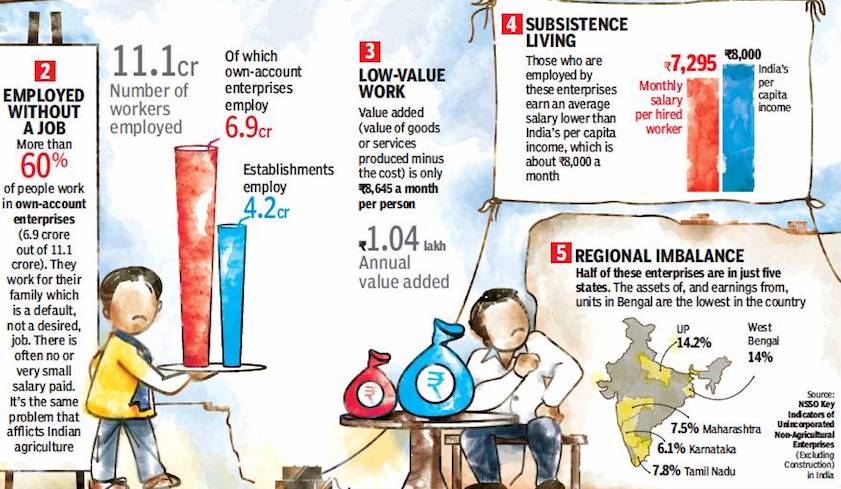

The retail-friendly Indian: A shop for every 15 families

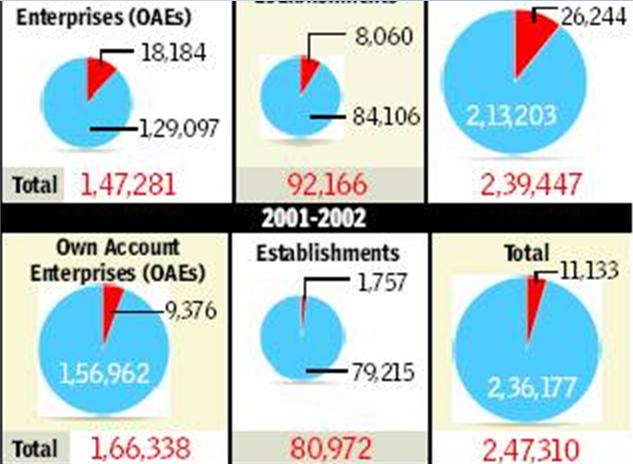

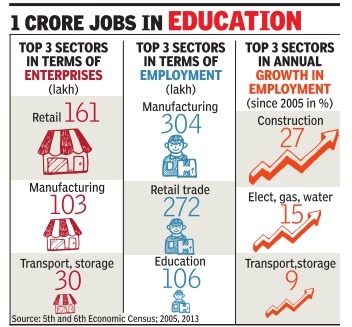

Indians continue to show their entrepreneurial spi rit -by opening more and more shops. With over 1.6 crore retail shops in the country -about one for every 15 families -this sector of work outguns every other.

Manufacturing, considered the backbone of prosperity for any economy , is second to retail with over 1 crore units. But manufacturing employs over 3 crore people beating retail trade, which has about 2.7 crore.

Transport companies, warehousing, hotels and eateries, and healthcare-related enterprises are other major occupations, while educational enterprises have emerged as major employers with over 2 million such businesses employing nearly 1.1million people.

These facts emerge from the 6th Economic Census con ducted by the government in 2013, detailed results of which were released earlier this year. The economic census counts all kinds of enterprises across the country except cultivation of crops and their ca re and protection. In this census, some 5.8 crore enterprises were counted, employing over 13 crore people. The previous one was done in 2005. The sector that has really boomed is construc tion, with employment growing at 27% per year. This is 2013 data so it will not reflect subsequent travails of the sector. Trade is in itself arguably the biggest employer if one adds up wholesale trade and sale and repair of motor vehicles which the census counted separately .

Putting all three together one gets about 1.8 crore enterprises employing 3.2 crore people, nearly 35 percent of all non-agricultural and non-extractive industries. This picture of a bustling economic hive with vast numbers involved in diverse enterprise building needs to be tempered with some economic cold water. Nearly 96% of all enterprises employ one to five workers, with just 1.4% employing more than 10 workers.

Compared to 2005, the share of enterprises in the 1-5 category has marginally increased. This indicates the atomised and dispersed nature of entrepreneurial activity, which, especially in the case of manufacturing, speaks of a rather low economic level. Of the three cr manufacturing enterprises, about a third, that is one crore, are working without any hired worker.

Economists have suggested earlier that retail trade is in fact a last resort for families seeking to boost incomes by selling a few items in villages or weekly haats. This transient nature of retail trade seems to be confirmed by the fact that 25% of these establishments are run from within homes and 17% are run without any fixed structure.

2013-17: professionals’ employment grew fastest in technology

From: Shilpa Phadnis & Avik Das, Fastest growing jobs in tech: Survey, September 6, 2018: The Times of India

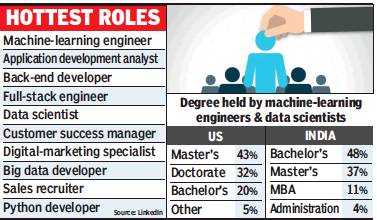

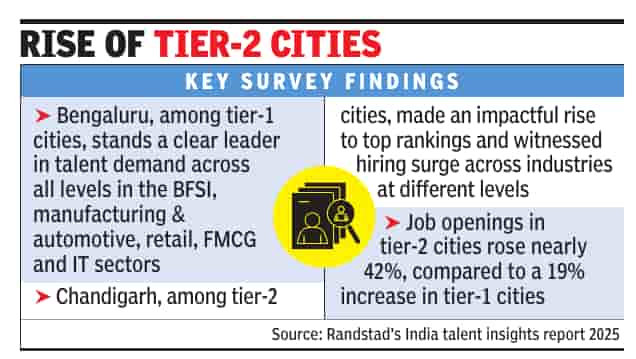

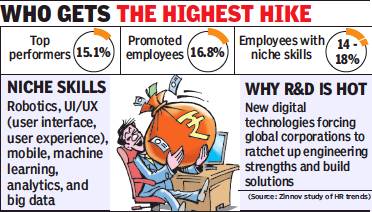

The top five — as also eight of the top 10 — fastest growing jobs for professionals in India are in technology, according to an analysis by LinkedIn, the world’s largest professional networking site.

The report is based on an analysis of data between 2013 and 2017 of the millions of LinkedIn members in India. It bolsters the idea that the country’s job market is making a seminal shift from the traditional engineering jobs to more niche ones requiring new skill sets. Just half a decade ago, the most prominent titles were software engineer and senior business analyst.

“In India, many businesses are shifting focus and resources to big data and digital products. Leaders across BFSI (banking, financial services & insurance), manufacturing, media & entertainment, professional services, retail & consumer products, and technology-software are looking at technology to drive scale, efficiency and growth. So machine-learning engineers and data scientists find themselves in massive demand,” the report said.

The report by LinkedIn, which is part of Microsoft, also shows that when it comes to qualifications for machine-learning and data scientist jobs, more than half the new workforce has just a basic bachelor’s degree — implying that companies train them on the job. Firms find it difficult to get highly qualified students who are industry-ready. In comparison in the US, roughly 17% of new graduates who take these jobs hold a doctoral degree — which would command a fatter pay cheque.

2016, Apr-Sept: 0.5% jobs added in 8 key non-farm sectors

Just over one lakh jobs were added between April 1 and October 1 last year in eight key non-farm sectors of the economy ranging from manufacturing and construction to ITBPO, education and health, according to a recent government report. Is this good or bad?

Considering that these eight sectors together employ over two crore workers, the net addition of new jobs amounts to a mere half a per cent of the total. So, it's bad news for the economy and another red flag for the government. The report in question is the third quarterly employ ment report, which was revamped by the government last year with new sectors included and a larger sample size of over 10,000 establishments.

The first report, released last year, set the baseline of employment as on April 2016. The report shows that employment is not only inching up at a painfully slow pace but also that aggregate figures hide more severe upheavals. For instance, almost three quarters of 1.09 lakh new jobs added are confined to two sectors -education and health, which added 82,000 new jobs. But the most worrying thing is manufacturing jobs grew by just 12,000 in six months -a rise of 0.1%. This sector, the backbone of the non-farm economy , employs nearly 50% of workers in the selected eight sectors. It has been the focus of the `Make in India' and `Skill India' programmes, as also of efforts to woo FDI. The Index of Industrial Production (IIP), re leased monthly by the government, confirms this dire situation with a rise of a mere 1% between January 2015 and January 2017.

According to latest data from the RBI, the same period saw gross bank credit to industries increasing by a mere 0.3%. This includes credit disbursals to micro, small, medium and large industries and together makes up nearly 40% of all non-food credit. The meager increase in credit to industry is a symptom of the flagging growth in manufac turing, which is also reflected in lack of job growth.

Further confirmation comes from second advanced estimates of national income and expenditure released by the government last month. Growth in investment in fixed capital known as gross fixed capital formation dipped by a factor of 10 between 2015-16 and 2016-17 from 6.1% to a shocking 0.6% in 2016-17. This implies that the corporate sector is not investing in new production arrangements.

Growth in gross value added (GVA) at basic prices -a measure of actual production -has slipped from 7.8% in 2015-16 to 6.7% in 2016-17.

2016-17: increase in some sectors, decrease in others

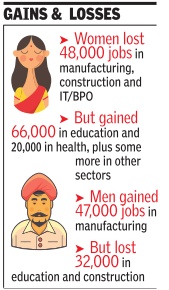

From: 87k jobs lost in mfg, but net addition of 64k in 8 core sectors: Govt data, February 20, 2018: The Times of India

Creating non-farm jobs remains a huge problem, with the government’s latest quarterly survey on employment in eight key sectors revealing that there’s been a net addition of just 64,000 jobs across these sectors between April and June last year. Even more worryingly, the manufacturing sector lost 87,000 jobs over this period, indicating that Make in India remains a distant dream.

The labour bureau’s quarterly survey shows that the education and health sectors between them added 1.3 lakh jobs in April-June 2017, while the other six sectors — manufacturing, construction, trade, transport, accommodation& restaurants, and the IT/ BPO industry — put together saw a net loss of 66,000 jobs.

Education was by far the biggest job creator, adding 99,000 jobs over this quarter. Health saw an addition of 31,000 jobs. The survey, which in its current format has been running since April 2016, covers both regular and casual employment as well as the selfemployed in these sectors.

Since April 2016, there has been a net addition of 4.8 lakh jobs in these eight sectors with over half from education (1.7 lakh) and health (1 lakh). That translates to a 2.3% growth in employment over 15 months, an annualised growth rate of barely 1.8%. This rate is not enough to even take care of new entrants to the job market each year, leave alone reducing unemployment.

Of 64k jobs in 2 mths in 2017, 51k went to women

The increase in employment in the manufacturing sector, the focus of the Make in India programme, is an even lower 1% over the 15-month period.

One positive spin-off of most new jobs being in the education and health sectors is that women have gained more than men. Of the net 64,000 new jobs created in April-June last year, 51,000 went to women and 13,000 to men.

Over the 15-month period since this survey began, however, female employment in these sectors has risen by a little over 2.1 lakh while male employment has gained about 2.7 lakh.

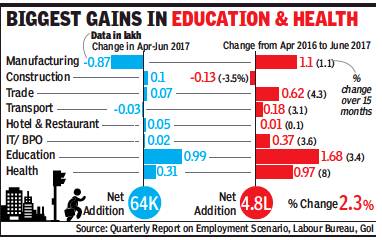

2018: legal, education sectors hire professionals aggressively

Legal, edu most dynamic in hiring, October 11, 2018: The Times of India

From: Legal, edu most dynamic in hiring, October 11, 2018: The Times of India

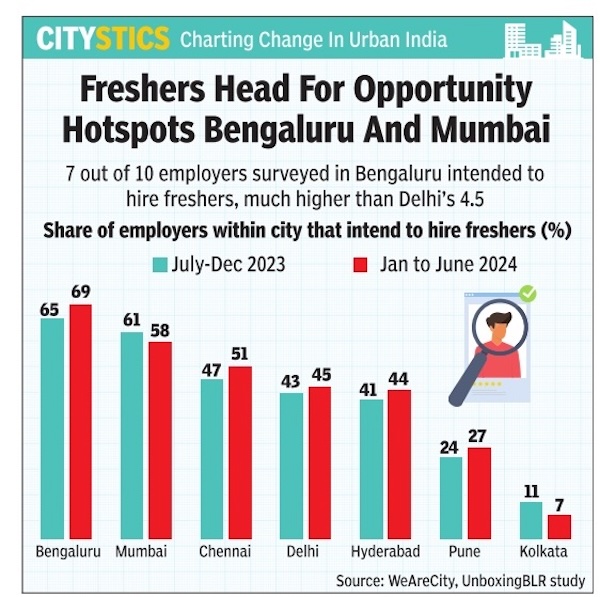

The legal and education sectors were the most dynamic in terms of hiring of professionals in the first half of 2018, according to the first edition of LinkedIn’s Workforce report for India. The study also found that software engineers were in demand by almost every industry, and that Kalyan, near Mumbai, was the region that attracted the most number of migrant professionals, followed by Bengaluru and Gurugram.

To measure the dynamism of sectors, LinkedIn looked at what it calls a net transition score — the difference between the total number of members who transitioned into the industry (from other industries), and the total that transitioned out. LinkedIn said the growth in the legal and education industries was driven by traditional roles such as associates, lawyers and researchers for the former and teachers and research assistants for the latter. “But what’s interesting is that these two industries, as also other industries, are active in hiring software engineers, application developers and those type of roles. It’s a requirement for digitisation of their businesses,” said Olivier Legrand, managing director, Asia Pacific and Japan, LinkedIn.

LinkedIn analysed the vast set of data on its India platform, including the 50 million member profiles, 50,000 skills, and 1 million company pages, for the period from January to June this year. The company will do such studies for every half year.

Design, recreation & travel, manufacturing, and nonprofits also drew significant numbers of professionals from other industries Kalyan emerged as the most in-demand migration corridor. LinkedIn defines indemand migration corridor as the movement of professionals into the top-10 most posted jobs of the destination region. In Kalyan, the movement was driven by the retail industry. Bengaluru was at No. 2, with the majority of migrants coming from Chennai, Hyderabad, Mumbai and Delhi, in that order.

Among the most sought-after occupations, software engineers are in pole position, followed by solutions consultants, Java software engineers and business analysts. The job posts for software engineer were highest in 8 of the 14 cities included in the study.

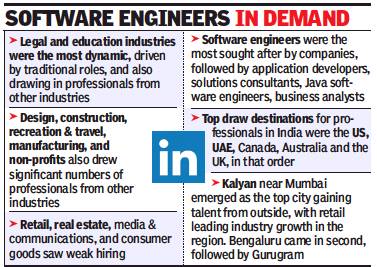

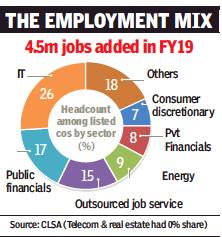

2018> 2019: The main sectors

August 17, 2019: The Times of India

From: August 17, 2019: The Times of India

See graphic:

The top employing sectors in 2019

A slowdown in the economy has begun to impact jobs, especially in the auto sector. However, Indian banks and IT firms contribute 41% of organised sector’s jobs, with the auto industry accounting for over 7%, says a study. The study, which covered 969 companies and three fiscals from FY17 to FY19, also showed that total jobs for the sample increased 6.2% in FY18, but far lower at 4.3% in FY19. Here's a look.

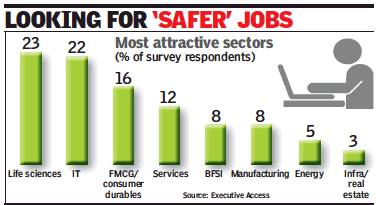

2020: Life sciences top draw for talent

Namrata Singh & Rupali Mukherjee, January 4, 2021: The Times of India

From: Namrata Singh & Rupali Mukherjee, January 4, 2021: The Times of India

For the first time perhaps, life sciences has emerged as the most preferred sector that is predicted to attract talent, ahead of IT and FMCG, this year.

In a survey by Executive Access, done exclusively for TOI, 23% of 261 CXOs across industries and geographies picked life sciences as the most attractive sector for talent. It is followed by IT (22%) and FMCG/consumer durables (16%). Candidates are increasingly looking for safer industries for work — those which witness minimum volatility and are insulated from the vagaries of the economy.

Ronesh Puri, managing director, Executive Access (India), said: “In 25 years, I have not seen life sciences topping the charts on being a talent attractor. Clearly, priorities have undergone a change for job-seekers. Candidates now prefer jobs that are meaningful and have potential to add value to society.” Given that Covid-19 has had a deep impact on the mindset of people, Puri said the thinking has also undergone a change. “Anecdotally also, people have come to us and said they want to work in the life sciences sector,” Puri said.

Healthcare may continue to attract talent, hospitality likely to take a hit

They find it to be more meaningful as it’s something that is protecting their loved ones. People look at purpose when they want to join an organisation. Prior to Covid, sectors like FMCG, IT and BFSI attracted the best talents. IT is seen as a sector that has changed the way we work, and is the second best after life sciences. FMCG too is insulated and would continue to be a talent magnet,” said Puri.

Pankaj Patel, chairman Zydus Group, said there will be tremendous opportunities for growth in the healthcare and life sciences sector in the decade that has just begun. Healthcare and life sciences has been a top contributor to the economy as well, and is expected to see breakthroughs in therapeutics, biologicals, vaccines and diagnostics. Patel said India will be at the forefront driving these possibilities globally, both in terms of research and innovation as well as manufacturing.

“This is a sector which has always been driven by knowledge, technology and skills and there will be a greater demand in the coming decade for young talent. Opportunities will open up for researchers, scientists, technologists and skilled professionals as the Indian healthcare industry continues to innovate, digitalize operations and explore newer technologies and tools like AI,” said Patel.

Sudarshan Jain, secretary general of Indian Pharmaceutical Alliance, said given that healthcare will be a high priority area for India, the sector will attract talent and it will be a satisfying arena to make a difference and contribute both to society and professional growth.

On the other hand, hospitality is predicted to take a dip in attracting talent, at least in the immediate aftermath of Covid-19. The long term attractiveness of the hospitality industry may pick up as travel normalises. It is clear that the industry is vulnerable to global crises and this may cause a talent exodus, according to the survey.

Other than the sectors of choice, candidates are also changing their preferences for the kind of organisation they would like to work with.

From a talent perspective, more than a quarter of the respondents still place job security at the forefront even as the economy slowly bounces back. However, some of the respondents are seizing the opportunity to look at new roles that would provide growth (19%), flexibility of remote working (18%) and job satisfaction (17%). Salary and compensation (money) now appears to have taken a backseat.

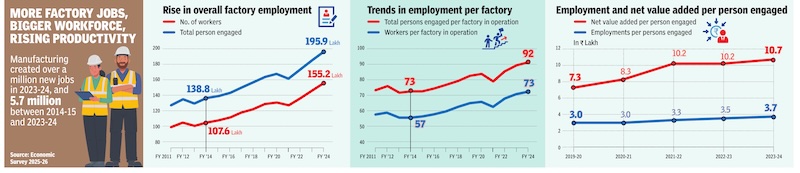

Factory Sector: 2011, 2019-2025

From: January 30, 2026: The Times of India

See graphic:

Trends in factory employment in India: 2011, 2019-2025

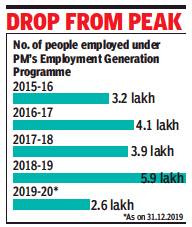

2015-20: Employment creation by govt. schemes

February 19, 2020: The Times of India

From: February 19, 2020: The Times of India

From: February 19, 2020: The Times of India

Some of the government’s flagship employment generation and placement schemes, such as the PM’s Employment Generation Programme (PMEGP) and Deendayal Antyodaya Yojana-National Urban Livelihoods Mission (DAY-NULM), are expected to see a steep decline in job creation during the current fiscal, going by data tabled in Parliament.

According to details provided by minister for labour and employment Santosh Kumar Gangwar, the number of jobs generated under PMEGP plummeted from about 5.9 lakh in 2018-19 to about 2.6 lakh in 2019-20 (until December 31, 2019). The fall is less sharp compared to 2017-18 when the number of persons benefited was 3.9 lakh.

PMEGP: Assam and J&K post sharpest dip in jobs growth

PM’s Employment Generation Programme is a credit-linked subsidy programme run by the ministry of micro, small and medium enterprises with Khadi and Village Industries Commission as the nodal agency for implementing the programme at the national level. The 2019-20 PMEGP figures are the lowest yet, since the NDA government assumed office in 2014.

Government data pointed to a steep decline in placement of people skilled under DAY-NULM, from 1.8 lakh in 2018-19 to a little over 44,000 in current fiscal, according to data until January 27, 2020. As with PMEG, 2018-19 saw a higher number than 2017-18 (115,416) and 2016-17 (151,901). The sharpest decline in job generation under PMEGP is in Assam and J&K. The DAYNULM drop was most drastic in states like Gujarat and MP.

Government data on the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Schemeshows a slowdown in 2019-20 with persondays generated falling from 26,796 in 2018-19 to 20,577, lowest since 2015-16. Again, the fall is less drastic compared to persondays in 2017-18 (23,373) and 2016-17 (23,565). The pace of skilling and placements under the Deen Dayal Upadhyaya Grameen Kaushalya Yojana (DDU-GKY) also declined with the number of persons trained falling from 2.4 lakh to 1.74 lakh, and the number getting jobs declining from 1.35 lakh in 2018-19 to 1.1 lakh this year. Here too 2018-19 stands out as high performing compared to previous years.

Employment provided by central public sector enterprises

See Employment, unemployment: India

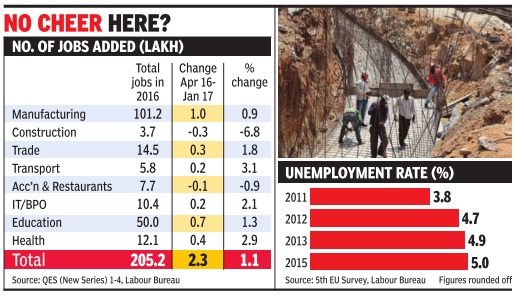

2016: Economy grew 7%, jobs 1%

Subodh Varma, Economy growing at 7%, jobs at 1%, May 19, 2017: The Times of India

Labour Bureau Report On Non-Farm Sector Highlights Growing Joblessness

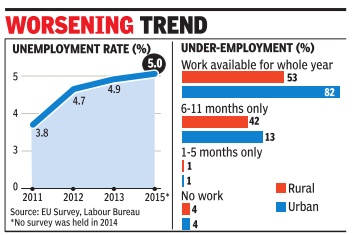

While the economy is growing at just over 7% per year, jobs increased by just 1.1% in 2016, according to a recently-released report covering eight key sectors of the non-farm economy . An earlier report had pegged joblessness at a fiveyear high of 5% in 2015, and under-employment at a staggering 35% of the over-15 years labour force. Seen in this context, the government is facing a growing employment crisis which its various initiatives are unable to address.

Both reports are based on large surveys carried out by the Labour Bureau. Job growth is tracked by a revamped quarterly survey of over 10,000 units while unemployment is recorded in an annual survey of 7.8 lakh people. The new quarterly survey started in April 2016 and replaced an earlier one which covered certain export-oriented sectors.

Providing decent jobs was one of the most popular promises which swept the Modi-led BJP to office in 2014 and helped it win several state elections.

Most recently, Yogi Adityanath too had promised to address the jobs situation in UP after being anointed the chief minister following BJP's dramatic victory in the state assembly elections.UP itself has an estimated 1 crore unemployed, according to the report. Recent reports of several IT and BPO majors shedding jobs have added to the worries of people, especially urban middle-class families which had been riding the IT boom. Global slowdown in IT services and components and new visa restrictions are thought to be behind this.

Several other indicators explain this painful situation. Gross credit given to industry has grown by just 6.7% in the past three years, the index of industrial production has inched up by just 6% and growth in gross fixed capital formation slipped to an alarmingly low 0.6% in January this year compared to 6.1% in 2016

A total of 2.3 lakh jobs were added to the eight sectors covered in the quarterly survey including manufacturing, construction, trade, transport, accommodation and restaurants, ITBPO, education and health.

Nearly half of the new jobs added were in education and health. Both these sectors are known for low paying jobs. Construction and the hospitalityfood sectors showed loss of jobs, the most serious ones, amounting to a dip of nearly 7%, is in construction.

One usually neglected aspect of India's unemployment crisis is of under-employment or concealed unemployment. This is of two types -not finding work for full year and work at very low wages. The Labour Bureau's 2016 report on unemployment paints a dire picture of both fronts.

Only 61% of people in the workforce were found to have year-round jobs with 34% working only 6-11 months even though they were willing to work for 12 months.

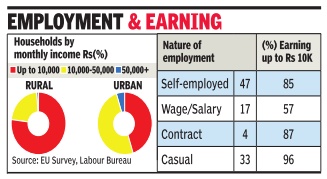

The report also revealed that 68% households were earning only Rs 10,000 per month or less. In all, nearly 16 crore people in the workforce were under-employed in this manner.

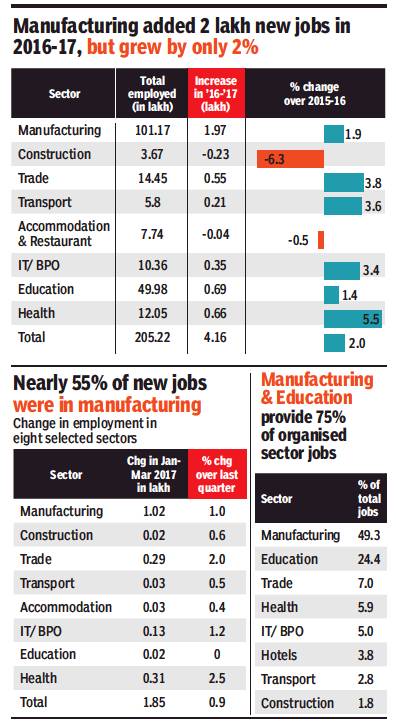

2016-17: jobs grew at 2%

Country’s organised sector created 4 lakh jobs in ’16-’17, December 31, 2017: The Times of India

From: Country’s organised sector created 4 lakh jobs in ’16-’17, December 31, 2017: The Times of India

2% Growth In New Jobs, Mfg Accounts For Nearly 50%

India’s organised sector created a little over 1,100 jobs a day in 2016-17 which totalled up to 4.16 lakh new jobs for the entire year. The rate of job creation was 2% higher than 2015-16. Last quarter of 2016-17, the hardest hit by the demonetisation, saw much higher job creation than the previous three quarters of the year, claims the quarterly report on employment scenario, released by the labour ministry. Nearly 45% of the total jobs created during the year were generated between January and March 2017.

Overall, the spell of low growth that casts a shadow on India’s economic performance, especially since the 1990s, continues. India has been adding about 8 lakh workers to its labour forceevery year, implying that organised sector absorbed only about50% of newworkers who seekemployment. However, the survey doesn’t reflect the overall employment situation in the country. It covers only the organised sector (establishments employing 10 or more persons) identified by Sixth Economic Census (2013-14). The census counted 58.5 million establishments of which only 1.4% came under organised sector.

Nearly half—47.4%--of the 4.16 lakh jobs created in 2016-17 were generated by the manufacturing sector. Education and health that accounted for 32% of the new jobs. An analysis of sectorwise change in employment shows that job market in health sector saw the largest expansion where 5.5% more people were employed on April 2017 as compared to April 2016. Health was followed by trade, transport and IT/BPO--each growing by over 3%. Together, these four sectors account for 21.3% of total employed people on April 2017. Construction and accommodation & restaurant industry saw a 6.3% and 0.5% decline in employment.

One encouraging finding of the survey was 87% of new job creation by employers. Self-employment constituted only 12.7% of the over four lakh jobs added in the financial year. peculiarity of India’s job market is the presence of large underemployment which disguises unemployment. Without a regular job and any unemployment benefit a large part of Indians classified as self-employed actually barely make a living. It is in this context that new job creation under by employers, rather than through self-employment, is a positive trend.

A gender-wise analysis shows 60.8% of new jobs were taken by men whilewomen got 39.2% of the newemployment.

2016-2018: 50 lakh men lost jobs

5m men lost jobs since 2016: Report, April 17, 2019: The Times of India

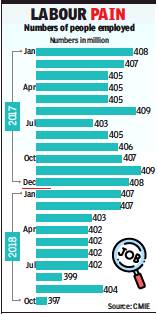

The State of Working India (SWI) 2019 report, released by the Bengaluru-based Azim Premji University has said that five million men lost their jobs between 2016 and 2018. The beginning of the decline in jobs coincides with demonetisation in November 2016, although no direct causal relationship can be established based only on these trends, adds the report.

The report has also found that in addition to rising unemployment among the higher educated, less educated workers have also seen job losses and reduced work opportunities since 2016.

The report on India’s labour market is based on the Consumer Pyramids Survey of the Centre for Monitoring the Indian Economy (CMIECPDX). CMIE is a Mumbaibased business information company with an independent think tank. This survey is an ongoing nationally representative panel survey of around 1.6 lakh households and 5.22 lakh individuals, conducted every four months.

“In the absence of official numbers from the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS), the only other household survey available for us to take stock of the employment situation is the Consumer Pyramids Survey of the Centre for Monitoring the Indian Economy (CMIE-CPDX),” said Amit Basole, associate professor at Azim Premji University.

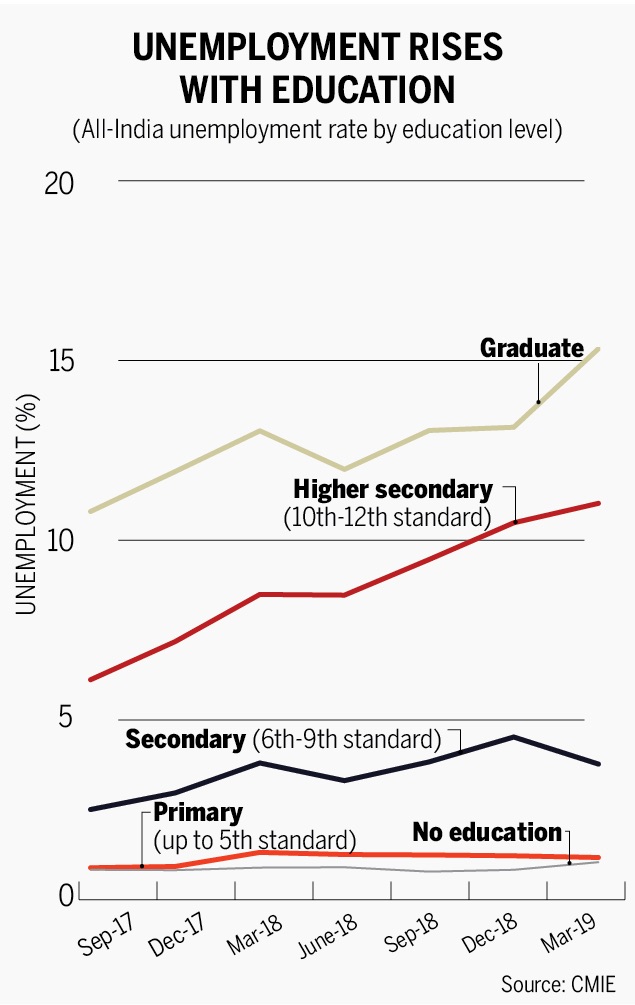

Rising unemployment among less educated

The report says that unemployment has risen steadily post 2011. “The overall unemployment rate to be around 6% in 2018, double of what it was in the decade from 2000 to 2011. In addition to rising open unemployment among the higher educated, the less educated (and likely, informal) workers have also seen job losses and reduced work opportunities since 2016”.

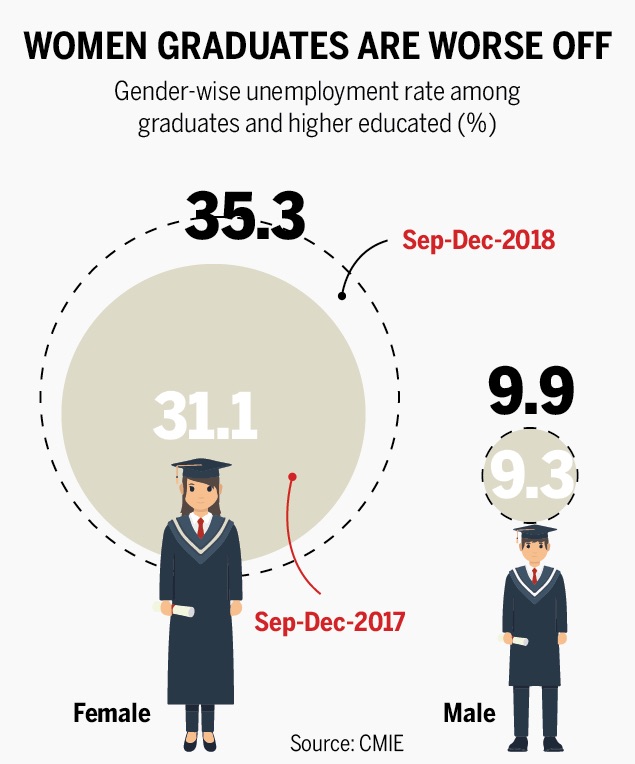

Women affected more

Among urban women, graduates are 10% of the working age population but 34% of the unemployed. The age group 20-24 years is over-represented among the unemployed. Among urban men, this age group accounts for 13.5% of the working age population but 60% of the unemployed. In general, women are much worse affected than men. They have higher unemployment rates as well as lower labour force participation rates.

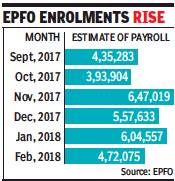

2017-18: EPFO enrolments rise, suggest healthy job growth

Payroll data shows healthy job growth, April 27, 2018: The Times of India

From: Payroll data shows healthy job growth, April 27, 2018: The Times of India

Over 35 lakh jobs were added in the formal economy in six months, according to the government’s first-ever estimate of payroll count based on Employees’ Provident Fund Organisation (EPFO) subscription and data from the Employees State Insurance Corporation and the Pension Fund Regulatory and Development Authority.

However, job creation slowed down in non-farm sectors during February as new member registrations with the EPFO declined to a four-month low of 4,72,075 during the month.

As many as 6,04,557 such members were registered in January 2018 and 5,57,633 in December 2017, the latest data released by EPFO about all non-zero contributors or new members that are registered with the body every month showed.

The number of all non-zero contributors registered with the EPFO was 6,47,019 in November, 3,93,904 in October and 4,35,283 in September last year.

From the PFRDA, the New Pension Scheme (NPS) data indicates generation of 4.2 lakh new payroll during the given period, that too only from Tier-I account. The NPS currently manages the corpus of around 50 lakh employees in state and the central government. For this study the central and state autonomous bodies have been shown under central and state governments respectively, while non-government refers to the corporate sector employees, a government statement said.

The EPFO said that these estimates may include temporary employees whose contributions may not be continuous for the entire year.

The EPFO has recently launched an aggressive drive to increase its coverage.

All establishments across the country with 20 or more employees whose basic wages are up to Rs 15,000 are required to be mandatory covered under the social security schemes run by the EPFO.

The payroll count is essentially the difference between the number of workers who joined and exited from the EPFO’s fold and as such is the net addition to jobs.

“It has now been decided to publish the age-band wise estimate of all new subscribers as declared by their employers. This data can be helpful in policymaking, planning and research work as the planners may have an idea as to what is the estimate of employees in different age band,” said a statement by Union labour ministry.

India has, for the first time, introduced monthly payroll reporting for the formal sector to facilitate analysis of new and continuing employment.

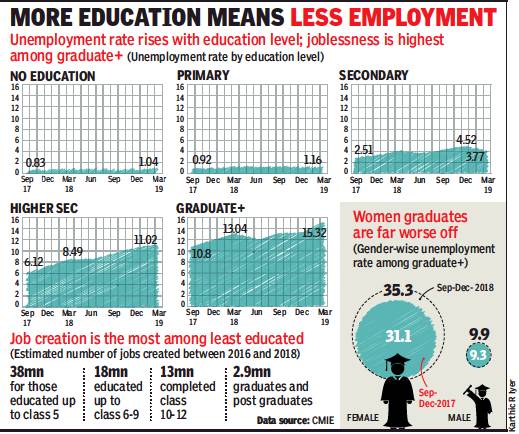

2018: 1 crore jobs, especially white collar, lost

Mahesh Vyas, Jobs Are Human Capital, April 11, 2019: The Times of India

From: Mahesh Vyas, Jobs Are Human Capital, April 11, 2019: The Times of India

Quality of Indian jobs is falling, there are fewer rewards for getting an education

Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy’s Consumer Pyramids Household Survey estimated a loss of over 10 million jobs in 2018. That was a big loss and there is no respite yet on this count. But a bigger loss on the jobs front is the loss of quality jobs.

Without getting into the gobbledygook of statisticians it is easy to notice the proliferation of tea and tobacco stalls, delivery boys, handymen, taxi drivers and the like. These are not jobs that educated people aspire for. At the same time, the availability of good jobs for engineers, MBAs and other post-graduate degree holders is not as prominent as it was about a decade ago.

IT companies and the financial markets are not as aggressive in hiring talent anymore as online and offline retail enterprises are in hiring labour to pack and deliver consumption goods. This shift in demand in favour of lower-skill labour implies that the premium for education in labour markets is declining.

A generation ago, it was inconceivable to get a job in the organised sectors without a graduation degree. This is no longer true. Today, the minimum education required to get a job in the organised sectors is much lower and is dropping.

Completion of graduation was not necessary for the BPO and call centre jobs, which were the fastest growing jobs in the early 2000s. In today’s fastest growing sector – the logistics industry – even higher secondary education is not necessary. These are jobs in the organised sectors.

Jobs are growing faster at the lower end of the education spectrum and not as much at the higher end.

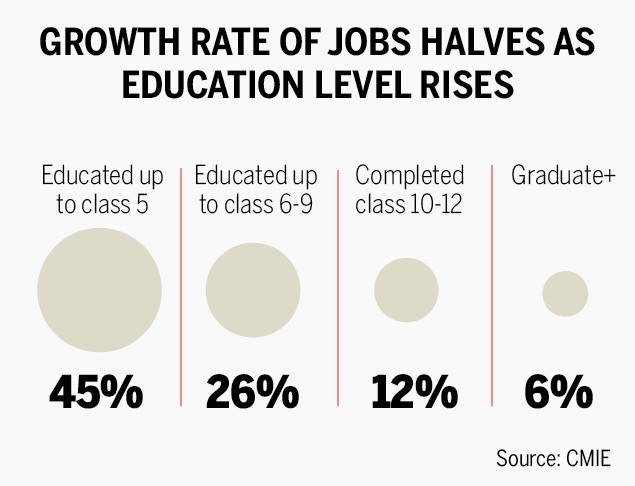

The Consumer Pyramids Household Survey quantifies the sharp fall in the rate of growth of jobs for the better educated in recent years. Over the last three years – between early 2016 and late 2018 – 38 million jobs were added for people who had completed only primary education, ie up to 5th standard. This implied that jobs for these barely educated people increased by nearly 45% over these three years.

In comparison, people who had acquired a little better education, ie between 6th and 9th standard, saw an addition of a much lesser 18 million jobs, implying also a lower 26% increase in jobs for these people.

The relationship between education and jobs gets worse as we go further up the education ladder. People who had completed secondary-to-higher secondary school education – 10th, 11th or 12th – saw a growth of 13 million jobs reflecting only a 12% growth over a three-year period.

Those with a graduate degree or a post-graduate degree saw the smallest growth in jobs between early 2016 and later 2018. These jobs grew by 2.9 million reflecting a growth of less than 6% over the three-year period.

Note that the growth rates of jobs keep halving as the education level rises – from 45% for the least educated to 26% for a small improvement, then 12% for secondary education and finally just 6% for the best educated.

The education composition of the employed is uninspiring. In late 2018, 55% or more than half of the employed workforce had not completed their 10th standard education.

If the quality of labour supply is nothing to be proud of, then the quality of jobs has to be correspondingly uninspiring. We see that while between 2016 and 2018 jobs have shrunk, the count of the self-employed has increased by nearly 20 million, which is a substantial 71% increase.

The self-employed are mostly those who could not find or retain a job during the age when most people begin their careers. After an age, when a person has no job offers on hand and when unemployment is not sustainable, then self-employment is the only option. Self-employment is rarely the preferred option at the beginning of a career.

In the past three years, this is the employment that has grown the most. There were 48 million self-employed people as of late 2018. Almost half of these emerged in the last three years – mostly in the form of small shops.

The self-employed include those who run small street stalls selling pan-beedi or pakora, etc, ferry goods on their hand-carts or boats, operate as insurance agents, brokers, etc. The better ones become taxi operators. Then, there are the freelancers like professional photographers, writers, who do gigs at their will. There is an entire range along the skills spectrum. Most of them are vulnerable.

The quality of work of most selfemployed persons is so poor that they do not even consider themselves to be employed. Neither do the daily wage labourers or agricultural workers. Only statisticians and labour economists consider these vulnerable workers to be employed. This gap between the definition of the specialists and the perceptions of their subjects needs to be narrowed.

Measurement of human capital in terms of the quality of jobs is important. Also, human capital is not merely years of education. Till the potential available in education is translated into quality jobs it is useless. Jobs are human capital, not just education.

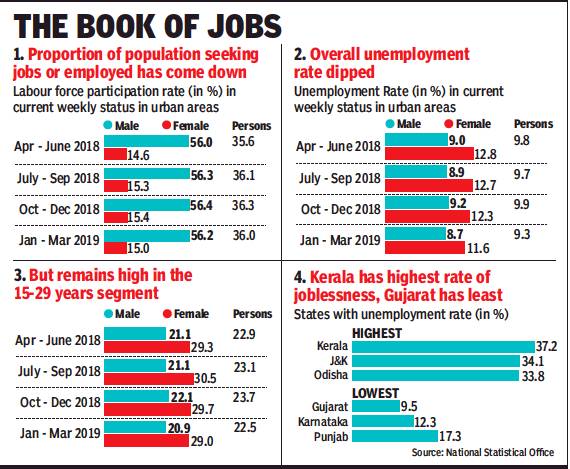

2018 Q2> 2019 Q1

Nov 25, 2019: The Times of India

From: Nov 25, 2019: The Times of India

The share of regular wage earners and salaried employees in the total urban workforce increased marginally between April-June 2018 and January-March 2019 — from 48.3% to 50% — with women faring better, the latest Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) released by the National Statistical Organisation showed.

According to data released, the rising trend has been maintained over the last four quarters, with salaried women, representing organised sector workers, seeing a 2.1 percentage point increase, compared to 1.5 percentage points for male workers.

In all, over a fifth of youths in cities available in the job market were unable to find employment in the last quarter of 2018-19, the PLFS data says. In January-March 2019, for which latest data is available, the survey estimates 22.5% unemployment rate in people aged 15 to 29 years.

Details

Mahesh Vyas, April 17, 2019: The Times of India

From: Mahesh Vyas, April 17, 2019: The Times of India

From: Mahesh Vyas, April 17, 2019: The Times of India

From: Mahesh Vyas, April 17, 2019: The Times of India

From: Mahesh Vyas, April 17, 2019: The Times of India

Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy’s Consumer Pyramids Household Survey estimated a loss of over 10 million jobs in 2018. That was a big loss and there is no respite yet on this count. But a bigger loss on the jobs front is the loss of quality jobs.

Without getting into the gobbledygook of statisticians it is easy to notice the proliferation of tea and tobacco stalls, delivery boys, handymen, taxi drivers and the like. These are not jobs that educated people aspire for. At the same time, the availability of good jobs for engineers, MBAs and other post-graduate degree holders is not as prominent as it was about a decade ago.

IT companies and the financial markets are not as aggressive in hiring talent anymore as online and offline retail enterprises are in hiring labour to pack and deliver consumption goods. This shift in demand in favour of lower-skill labour implies that the premium for education in labour markets is declining.

A generation ago, it was inconceivable to get a job in the organised sectors without a graduation degree. This is no longer true. Today, the minimum education required to get a job in the organised sectors is much lower and is dropping. The Consumer Pyramids Household Survey quantifies the sharp fall in the rate of growth of jobs for the better educated in recent years. Over the last three years – between early 2016 and late 2018 – 38 million jobs were added for people who had completed only primary education, i.e. up to 5th standard. This implied that jobs for these barely educated people increased by nearly 45% over these three years.

In comparison, people who had acquired a little better education, i.e. between 6th and 9th standard, saw an addition of a much lesser 18 million jobs, implying also a lower 26% increase in jobs for these people.

The relationship between education and jobs gets worse as we go further up the education ladder. People who had completed secondary-to-higher secondary school education – 10th, 11th or 12th – saw a growth of 13 million jobs reflecting only a 12% growth over a three-year period.

Those with a graduate degree or a post-graduate degree saw the smallest growth in jobs between early 2016 and later 2018. These jobs grew by 2.9 million reflecting a growth of less than 6% over the three-year period.

Note that the growth rates of jobs keep halving as the education level rises – from 45% for the least educated to 26% for a small improvement, then 12% for secondary education and finally just 6% for the best educated. The education composition of the employed is uninspiring. In late 2018, 55% or more than half of the employed workforce had not completed their 10th standard education.

If the quality of labour supply is nothing to be proud of, then the quality of jobs has to be correspondingly uninspiring. We see that while between 2016 and 2018 jobs have shrunk, the count of the self-employed has increased by nearly 20 million, which is a substantial 71% increase. The self-employed are mostly those who could not find or retain a job during the age when most people begin their careers. After an age, when a person has no job offers on hand and when unemployment is not sustainable, then self-employment is the only option. Self-employment is rarely the preferred option at the beginning of a career.

In the past three years, this is the employment that has grown the most. There were 48 million self-employed people as of late 2018. Almost half of these emerged in the last three years – mostly in the form of small shops.

The self-employed include those who run small street stalls selling pan-beedi or pakora, etc, ferry goods on their hand-carts or boats, operate as insurance agents, brokers, etc. The better ones become taxi operators. Then, there are the freelancers like professional photographers, writers, who do gigs at their will. There is an entire range along the skills spectrum. Most of them are vulnerable.

The quality of work of most self-employed persons is so poor that they do not even consider themselves to be employed. Neither do the daily wage labourers or agricultural workers. Only statisticians and labour economists consider these vulnerable workers to be employed. This gap between the definition of the specialists and the perceptions of their subjects needs to be narrowed.

Measurement of human capital in terms of the quality of jobs is important. Also, human capital is not merely years of education. Till the potential available in education is translated into quality jobs it is useless. Jobs are human capital, not just education.

The clamour for jobs

Mahesh Vyas, April 17, 2019: The Times of India

March 2018

2.8 crore people apply for 90,000 jobs with the Indian Railways

February 2018

Around 19 lakh candidates, including 992 PhDs and 23,000 MPhil degree holders apply for 9,500 posts of typists, stenographers and village administrative officers in Tamil Nadu

August 2018

93,000 applicants apply for 62 posts of messengers at the telecom wing of UP Police. Applicants for the job - for which minimum eligibility is class V - included 3,700 PhD holders, 28,000 PGs and 50,000 graduates

February 2019

Around 4,600 apply for 14 sweepers’ posts in Tamil Nadu; majority of applicants had B.Tech, M.Tech, MBA degrees

April 2019

Engineers, lawyers, CAs, MBAs among 12,453 interviewed for 18 Class IV posts at Rajasthan Assembly Secretariat. An MLA’s son got the job

54% of jobs were at listed cos in IT, finance

Mayur Shetty, Sep 11, 2019: The Times of India

From: Mayur Shetty, Sep 11, 2019: The Times of India

IT & financial services have turned out to be the biggest employers — both account for half of the jobs among all listed companies. Incidentally, these two sectors are also the biggest hirers of women.

A study of the top 250 listed companies by investment bank CLSA has shown that of the total 45 lakh jobs generated by them, more than half were in just the two sectors, with financials employing 28% of the total workforce, or 13 lakh people, and IT another 26%. Within financials, the public sector employs 60% of the workforce.

Private firms continue to be the main source of job-creation, as public-sector headcount declined 2.6% in FY19. Private-sector headcount, on the other hand, increased by 9.2%. The decline in publicsector jobs was the sharpest seen in recent years. The two biggest listed public-sector employers — Coal India and SBI — on a net basis, cut their workforces yearon-year (YoY) by 4.4% and 2.6% respectively.

In the report ‘Boardroom nectar — Distilling the essence of India’s annual reports’ by Mahesh Nandurkar and Abhinav Sinha, job growth among listed companies in FY19 was 4.1% YoY for a comparable set of 238 companies, rising from 1.4% growth in FY18. This was a three-year high. “If we add the three large outsourcing job service providers, then the growth rises to 6%. In absolute terms, nearly 0.25 million net jobs were created during the year,” the report said.

At almost 420,000 employees, TCS has the largest workforce of all the listed companies in India. TCS has employed the largest number of women — at 152,114 female employees — accounting for 36% of their workforce. Infosys has the highest proportion of women in their workforce, at 37%. The biggest hiring increase was by Quess Corp, which hired 56,300 employees in the last year.

Public sector companies have shrunk their workforce for the second consecutive year, which is largely through attrition as there has not been any major separation scheme. One outcome of this attrition is that the average age is coming down.

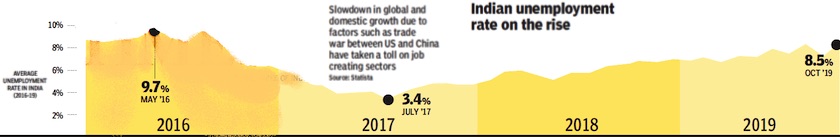

Mar, Apr 2019: Jobless rate highest since 2016: CMIE

May 3, 2019: The Times of India

Jobless rate highest since October 2016: CMIE data

New Delhi:

India’s unemployment rate in April rose to 7.6%, the highest since October 2016, and up from 6.7% in March, according to data compiled by the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE). “The lower unemployment rate in March was a blip, and it has again climbed following the trend of earlier months,” Mahesh Vyas, head of CMIE, said.

The figures could be a setback for PM Narendra Modi during a general election that will end on May 19, with opposition parties criticising the government over weak farm prices and low job growth. The government recently withheld jobs data because officials said they needed to check its veracity. India usually releases official unemployment data every five years. But December unemployment figures were leaked and showed that the jobless rate rose to its highest level in at least 45 years in 2017-18. The government has said it will release jobs data once a year. CMIE said in a report released in January that nearly 11 million people lost jobs in 2018 after the demonetisation in late 2016, and new goods and services tax (GST) in 2017 hit millions of small businesses. REUTERS

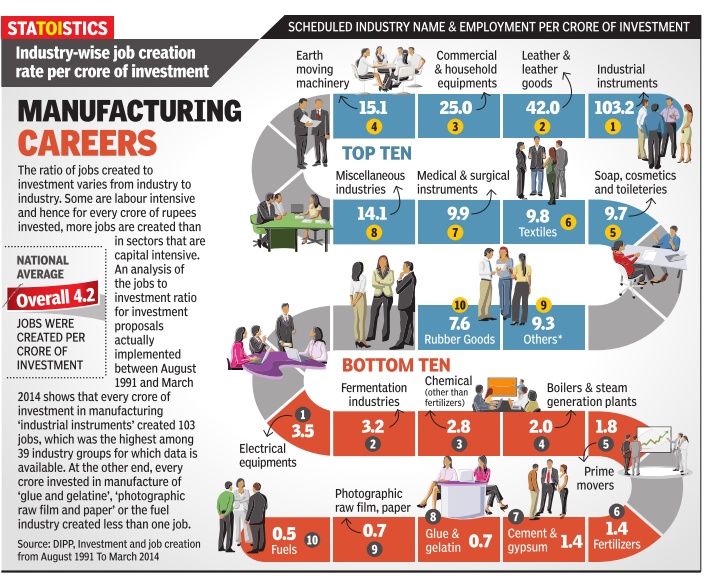

Jobs to Investment ratio

1991-2014

See graphic. 1991-2014: Employment created for every Rs.1 crore of investment

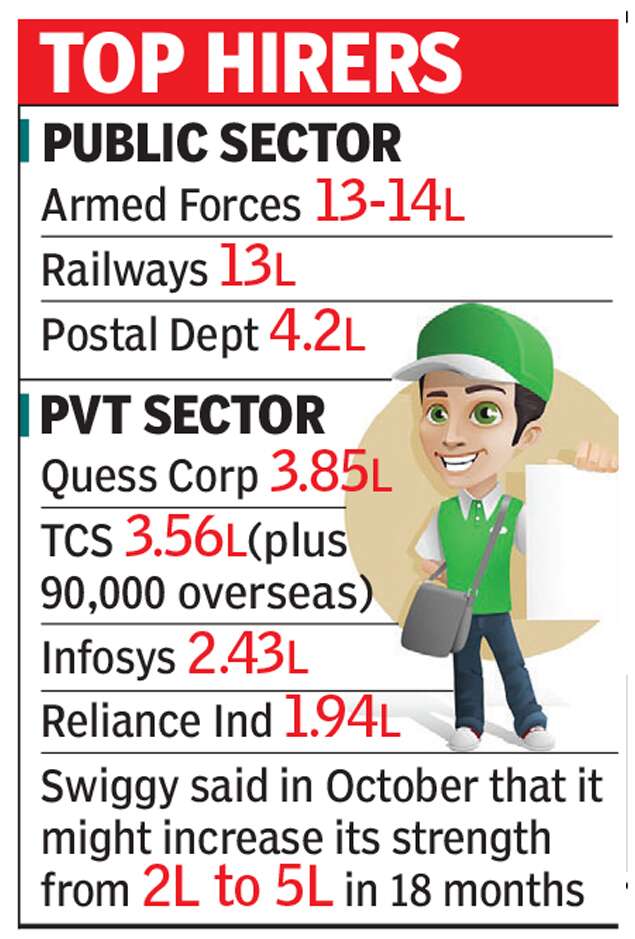

As in 2020

Madhav Chanchani, Digbijay Mishra, February 5, 2020: The Times of India

From: Madhav Chanchani, Digbijay Mishra, February 5, 2020: The Times of India

Heard of this firm? It’s now India’s largest private sector employer

BENGALURU: Next time you see an Amazon delivery executive in your locality or walk into a Samsung store for after-sales service, you will probably be dealing with an employee of Quess Corp — a company you most probably haven’t heard of.

Going by its latest quarterly filing, the Bengaluru-based company, which provides staffing solutions for some of the biggest brands in the country, now has the largest roster of employees and associates — 3.85 lakh — in the private sector in India.

Growing at 38% every year since 2016, Quess has shot past Tata Consultancy Services (TCS), which remains the largest overall employer with 4.46 lakh on the rolls, but of whom about 90,000 are overseas, pegging its India workforce at about 3.6 lakh, according to people briefed on the matter. TCS does not provide a geographic split of its employee base and a company spokesperson declined to comment for the story.

The development underlines a growing shift in the economy as companies like Quess have benefited from the demand for outsourced workers in areas ranging from e-commerce delivery to facilities management for commercial buildings.

There is, of course, a significant difference in the skill levels of staff at TCS, which mostly employs engineers, and Quess, which depends largely on ‘grey-collar’ workers.

Quess’s employees function as outsourced service providers for its over 2,000 clients, including Samsung, Amazon, Reliance, Vodafone India and Bajaj Finance, according to a report from ICRA. The company has about 5,000 workers overseas in markets like Singapore.

“There are many countries which have a population smaller than the number of employees we have. The scale of our impact on the Indian job market is not well-known, especially the role we play in formalizing the job economy,” said Quess Corp's Group CEO Suraj Moraje, a former McKinsey & Co partner who joined the company in November.

The development comes at a time when traditional sectors such as automobiles, telecom, FMCG and even IT services have seen layoffs for reasons like slowing growth and consolidation. At the same time, new economy companies continue to grow, fuelled by a record year of capital inflows.

Investors tracking the space say the shift is happening not only because of the scarcity of jobs, but also because wages have increased substantially in the segment. “This area is exploding and these grey-collar jobs now have salaries which compare with entry-level compensation in IT/ITes companies,” says Anand Lunia, founding partner at venture capital firm India Quotient, adding that wages for delivery boys have risen faster than inflation over the last decade.

Lunia was an early investor in Rebel Foods, which owns brands like Faasos and Behrouz Biryani, where salaries of delivery personnel are about Rs 20,000 – compared to Rs 6,000-7,000 in 2010, which inflation-adjusted, would have been about Rs 10,000-12,000 now.

“Their aspiration is a steady job, which is a big reason why companies outsource these jobs since attrition is high and there is also not always a steady demand for these roles,” he said.

According to Moraje, the average salaries at Quess range between Rs 12,000-Rs 40,000 for 70% of its workforce, about 75% of whom are in the age group of 21-35. While he declined to give an attrition number, the firm interviews over 1 million people a year. “We need to make sure that employees and associates have a career path so that our recruiting costs and retention rate improve,” he says. The company says it provides benefits such as provident fund and insurance to its entire workforce, and for many of them, this is their first formal employment.

Quess, which was started by serial entrepreneur Ajit Isaac over a decade ago, has grown at a fast clip through a slew of acquisitions and the backing of Fairfax, owned by Canadian billionaire Prem Watsa. The company was listed in 2016. Local rival TeamLease, also based in Bengaluru, had about 2.28 lakh employees and trainees as of December 2019. Other major players in the space include global giants like Adecco and Randstand.

“Companies are focusing on their core activities, while outsourcing activities that can be done by a specialised company; Quess Corp fits in there. Companies are wary of employing full-time when they can find gigs to fill in the jobs,” said Mahesh Vyas, MD & CEO at CMIE (Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy). He added that whether benefits are provided or not will be critical to measure if such employment are sustainable. “If a larger part of the labour force is getting into engagement that does not give social security, in a generation’s time, we could have a problem.”

Employment creation is inadequate

1947-2015: some statistics

Generous pay for employees, Vivek Rae, December 7, 2015: India Today

Vivek Rae was a member of the Seventh Central Pay Commission.

A study commissioned by the Seventh CPC through IIM-Ahmedabad with respect to 40 job families shows that government functionaries at lower levels are being paid much higher salaries and allowances compared to their private sector comparators.

At Rs 18,000 per month, the minimum salary is much higher than the minimum wage notified by state governments.

The Seventh Central Pay Commission (CPC) submitted its report on November 19 and its recommendations will apply during 2016-2025. The recommendations have been greeted with a storm of protest by major government employees' associations on the ground that the increase in pay at lower levels is inadequate.

The Central Pay Commission, set up every 10 years, has the complex task of setting the emolument structure for a wide spectrum of government employees and pensioners, covering about 4.7 million serving employees and 5.2 million pensioners. Conflicting considerations relating to attracting talent, addressing equity issues and fiscal sustainability make this exercise a difficult balancing act. Pay panel reports also provide the baseline for revision of salaries in state governments, public-sector enterprises, universities and autonomous bodies. The economy-wide financial implications are therefore significant.

An overview of the central government pay structure reveals the following:

1. The number of pay scales in government, which peaked at 500 in 1972-73, will come down to 18 in 2016. This indicates massive rationalisation and delayering of bureaucracy.

2. The real increase in the minimum pay, at 14.3 per cent, although modest compared to 54 per cent in the Sixth CPC and 31 per cent in the Fifth CPC, is based on the Aykroyd formula (based on nutrition intake of an average Indian adult) in practice since 1957.

3. The ratio of minimum salary in government to national per capita income has ranged from 2.5-2.6 since the 1960s and continues to be about 2.5 under the Seventh CPC. This ratio is much lower in OECD (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development) countries and indicates that central government employees in India earn much more than the average citizen in comparison with the OECD countries. At Rs 18,000 per month, the minimum salary compares favourably with the minimum wage notified by different state governments and is much higher if allowances are included.

4. The per capita expenditure on pay and allowances was Rs 3.92 lakh per annum in 2012-13, or about Rs 32,500 per month. This was about five times higher than the national monthly per capita income.

5. Previous comparisons between the minimum and maximum salary yielded a ratio of 1:36.4 in 1946-47, which declined to 1:11.4 by 2006. However, the appropriate comparison is not between the minimum and maximum salary in government but the entry pay at the lowest level (Group C) compared with the entry pay at officer level (Group A). The recommended salary of Rs 18,000 per month at Group C level compared with the entry salary of Rs 56,100 per month at Group A level yields a ratio of 1:3 and not 1:12.5, as is generally believed. The proposed pay structure, therefore, incorporates a high level of equity.

6. A study commissioned by the Seventh CPC through IIM-Ahmedabad with respect to 40 job families shows that government functionaries at lower levels are being paid much higher salaries and allowances compared to their private sector comparators. The reverse is the case for officers at senior levels. Group A officers account for only 2.8 per cent of personnel (excluding defence forces).

Personnel in position in central government (excluding defence forces) has remained static over the last 10 years at 3.3 million. Excluding central police forces, persons in position declined from 2.52 million in 2006 to 2.32 million in 2014. The intake of new civilian recruits during 2006-2014 has been about 1 lakh per year. This constitutes about 1 per cent of annual addition to the work force. Central government jobs are clearly not a solution for unemployment.

Financial impact

The impact of recommendations of the Seventh CPC is estimated at 0.66 per cent of the GDP in 2016-17, which is lower than the impact of 0.77 per cent of the GDP after the Sixth CPC in 2008-09. However, expenditure on pay, allowances and pensions (PAP) which increased from 14 per cent of the government revenue expenditure in 2007-08 to 18 per cent in 2008-09 (excluding Railways) is likely to go up to 22 per cent in 2016-17. A larger share of government spending is being accounted for by PAP. Expenditure on pay and allowances has also accounted for an increasing share of defence revenue expenditure, having increased from 40 per cent during 1995-96 to 60.81 per cent in 2009-10 (after Sixth CPC).

An innovative risk and hardship matrix has been designed to encapsulate the entire spectrum of risk and hardship allowances. These measures will enable government to further rationalise allowances in the medium-term.

While it is not possible to reconcile conflicting objectives and satisfy all stakeholders, the pay package recommended by the Seventh CPC has been generous by any standard.

Salary growth, 2008-16: 0.2%; GDP growth 63.8%

India's salary growth at 0.2%, GDP gain of 63.8% since 2008, PTI | Sep 15, 2016

- India has seen a salary growth of just 0.2 per cent since 2008.

- However, Indian econony grew by 63.8% since 2008.

- China recorded the largest real salary growth of 10.6% in this period.

- The US suffered one of the worst salary recoveries among developed nations.

India has seen one of the lowest pay rises since 2008.

NEW DELHI: India has seen a salary growth+ of just 0.2 per cent since the great recession eight years back, while China recorded the largest real salary growth of 10.6 per cent during the period under review, says a report.

According to a new analysis by the Hay Group division of Korn Ferry, India's salary growth+ stood at 0.2 per cent in real terms, with a GDP gain of 63.8 per cent over the same period.

During the period under review, China, Indonesia and Mexico had the largest real salary growth at 10.6 per cent, 9.3 per cent and 8.9 per cent, respectively.

Starting salaries in India amongst lowest in Asia-Pacific: Study

Meanwhile, some other emerging markets including Turkey, Argentina, Russia and Brazil had the worst real salary growth at (-) 34.4 per cent, (-) 18.6 per cent, (-) 17.1 per cent and (-) 15.3 per cent, respectively.

"Most emerging G20 markets+ stood at either one end of the scale or the other either amongst the highest for wage growth, or amongst the lowest. However, India stood right in the middle, with all the mature markets," the report said.

The report further noted that Indian wage growth is the most unequal.

"Of the countries we looked at, Indian wage growth was by far the most unequal - people at the bottom are 30 per cent worse off in real terms since the start of the recession; whilst people at the top are 30 per cent better off," Benjamin Frost, Korn Ferry Hay Group Global Product Manager - Pay said.

Strong wage growth for senior jobs is mostly because of skill shortages for key professional and managerial roles; and the increasing connection to a more globalised pay market at the senior levels - a market where India still pays less than most countries, but is catching up fast, Frost said.

Regarding the poorer wage growth at the bottom, the report noted that it is more because of an oversupply of people.

"India has made less progress than some other countries in bringing high value jobs to the country. This has led to poor job growth, therefore an oversupply of un/semi-skilled people, and poor wage growth," Frost said.

2004-2010: Jobless growth?

‘Jobless growth’ during UPA-1, admits Centre

Self-Employed Dropped From 56.4% To 50.7% Of Workforce

Rajeev Deshpande TNN

New Delhi: Some 20 months after hotly contesting data on UPA-1’s “jobless growth”, the government has admitted to lack of substantial increase in employment between 2004-05 and 2009-2010, with the selfemployed workforce shrinking from 56.4% to 50.7% of the total workforce.

In absolute numbers, the self-employed decreased from 258.4 million to 232.7 million in this period while regular salaried workers rose from 69.7 million to 75.1 million. The ranks of casual labour rose from 129.7 million to 151.3 million. In all, the total workforce increased from 457.8 million to 459.1 million, a rise of just 0.3% over this period.

The ministry of planning has identified limited flexibility in “managing” the workforce, high cost of complying with labour regulations, poor skill development and a vast unorganized sector as reasons for dissatisfactory growth in employment.

Responding to Parliament’s finance standing committee’s query on why India was not creating enough productive jobs, the ministry said while the number of salaried employees increased, the selfemployed segment declined.

Interestingly, the ministry referred to the same 66th round of the National Sample Survey Organization that irked the government in June 2011 with Planning Commission deputy chairperson Montek Singh Ahluwalia slamming the report as inaccurate.

The controversy deeply embarrassed the ruling coalition as the data seemed to negate the Manmohan Singh government’s “inclusive growth” slogan despite policy initiatives intended to make growth less uneven.

Under official pressure, the NSSO later put down the employment statistics to factors like rising incomes resulting in women choosing to stay at home instead of taking up physically challenging jobs.

Yet , the planning ministry that has told the finance committee “India had an average growth rate of 7.9% in the 11th plan. However, this growth did not lead to increase in employment opportunities”.

Stating that the NSSO data exhibited a shift in employment status, the ministry said in the period 2004-05 to 2009-10, the percentage of regular salaried workers increased from 15.2% to 16.4% and there was a jump in casual labour from 28.3% to 33%. It indicates that informal employment that accompanies new real estate development, industry and urbanization has lagged.

This would include service providers like road side eateries, local transport, small shops and services like appliance repair.

The planning ministry did not explain the jump in casual labour but this could due to the rural employment guarantee scheme, although the government has also argued that the trend contradicts claims of slow employment.

The numbers may look even less flattering when the next bunch of statistics is available in view of the plummeting growth.

The government has listed measures like boosting manufacturing, developing skills, promoting labour intensive sectors and simplifying labour laws as an antidote to the employment logjam.

GOING SLOW

Percentage of self-employed dropped from 56.4% of total workforce in 2004-05 to 50.7% in 2009-10

Percentage of regular employees rose from 15.2 to 16.4 and of casual labourers from 28.3 to 33

In absolute numbers, number of self-employed was 258.4m in 2004-05 and 232.7m in 2009-10

There were 69.7m regular workers in 2004-05 and 75.1m in 2009-10

Casual labourers rose from 129.7m to 151.3m

Total workforce rose from 457.8m in 2004-05 to 459.1m in 2009-10, an increase of just 0.3% Casual labour grew from 28% to 33%

2004-10: Fifty lakh jobs lost?

The Times of India, Aug 23, 2015

5 million jobs lost during high-growth years, says study

As many as five million jobs were lost between 2004-05 and 2009-10 — paradoxically during the time when India's economy grew at a fast clip — an Assocham study said.

This has put a question mark on whether economic expansion should be linked to job creation, according to the study.

Moreover, it observed that over-emphasis on services and neglect of the manufacturing sector are mainly responsible for this "jobless growth" phenomenon. Even as about 13 million youth are entering labour force every year, the gap between employment and growth widened during the period, the study noted.

"The Indian economy went through a period of jobless growth when five million jobs were lost between 2004-05 and 2009-10 while the economy was growing at an impressive rate," Assocham said.

Quoting Census data, it said the number of people seeking jobs grew annually at 2.23 per cent between 2001 and 2011, but growth in actual employment during the same period was only 1.4 per cent.

"This large workforce needs to be productively engaged to avoid socio-economic conflicts," Assocham secretary general D S Rawat said.

The changing demographic patterns, he said, suggest that today's youth is better educated, probably more skilled than the previous generation and highly aspirational.

"In a service-driven economy, which contributed 67.3 per cent (at constant price) to GDP but employed only 27 per cent of total workforce in 2013-14, enough jobs will not be created to absorb the burgeoning workforce," Assocham added.

Experts argue that the growth of manufacturing will be key for growth in income and employment for multiple reasons. For every job created in the manufacturing sector, three additional jobs are created in related activities.

In 2013-14, manufacturing contributed 15 per cent to GDP and employed about the same percentage of total workforce, a sign that the sector has a better labour absorption compared with services.

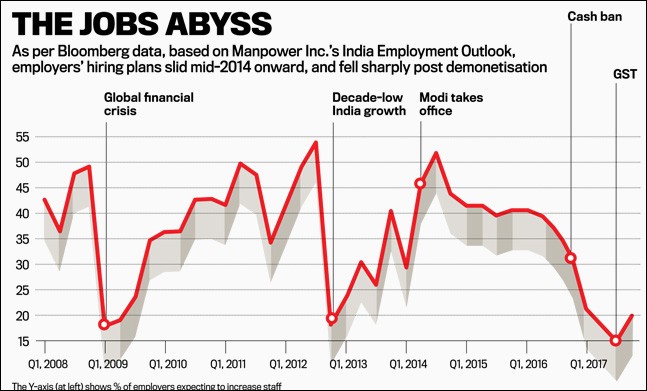

Employer’s recruitment plans: 2008-2017

See graphic

From 2011 to 2016 new jobs declined from 9 lakh to 1.35 lakh

PTI |7 million jobs can disappear by 2050, says a study, Oct 16, 2016

- As many as 550 jobs have disappeared every day in last four year, a study has claimed

- India created only 1.35 lakh jobs in 2015 in comparison to 4.19 lakh in 2013 and 9 lakh in 2011

- The data clearly points to the fact that job creation in India is successively slowing down

As many as 550 jobs have disappeared every day in last four years and if this trend continues, employment would shrink by 7 million by 2050 in the country, a study has claimed.

Farmers, petty retail vendors, contract labourers and construction workers are the most vulnerable sections facing never before livelihood threats in India today, the study by Delhi-based civil society group PRAHAR has said.

As per the data released by Labour Bureau early 2016, India created only 1.35 lakh jobs in 2015 in comparison to 4.19 lakh in 2013 and 9 lakh in 2011, the group said in a statement.

"A deeper analysis of the data reveals a rather scary picture. Instead of growing, livelihoods are being lost in India on a daily basis. As many as 550 jobs are lost in India every day (in last four year as per Labour Bureau data) which means that by 2050, jobs in India would have got reduced by 7 million, while population would have grown by 600 million," the statement said.

The data clearly points to the fact that job creation in India is successively slowing down, which is very alarming, it pointed out.

"This (rise in unemployment) is because sectors which are the largest contributor of jobs are worst-affected. Agriculture contributes to 50 per cent of employment in India followed by SME sector which employs 40 per cent of the workforce of the country," the statement said.

The organised sector actually only contributes a minuscule less than 1 percentage of employment in India. India has only about 30 million jobs in the organised sector and nearly 440 million in the unorganised sector.

According to the World Bank data, percentage of employment in agriculture out of total employment in India has come down to 50 per cent in 2013 from 60 per cent in 1994.

It said that the labour intensity of small and medium enterprises is four times higher than that of large firms.

It further said that the multinationals are particularly capitalistic a fact vindicated during investment commitments of USD 225 million made for the next five years during the Make in India Week in February 2016.

However, what went unnoticed is that these investments would translate into creation of only 6 million jobs, it said.

"India needs to go back to the basics and protect sectors like farming, unorganised retail, micro and small enterprises which contribute to 99 per cent of current livelihoods in the country. These sectors need support from the Government not regulation. India needs smart villages and not smart cities in the 21st century," it added.

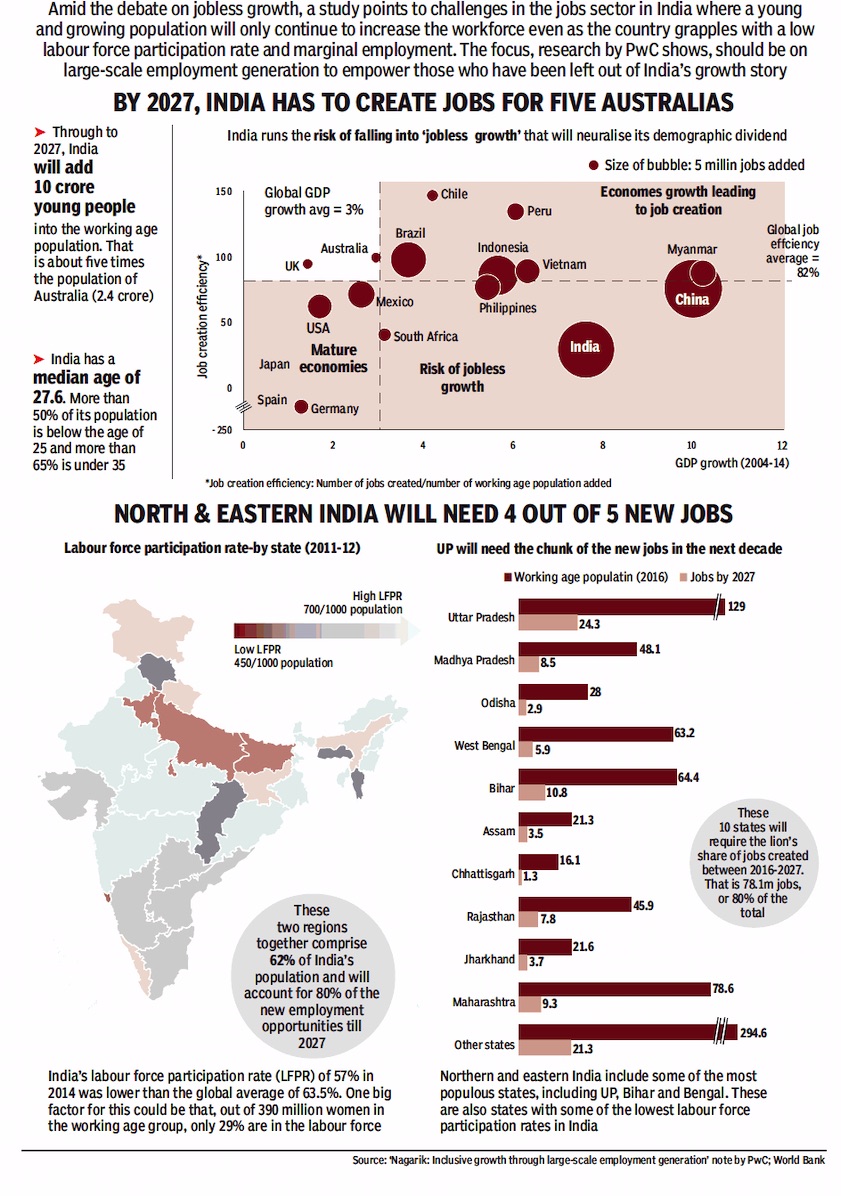

2011-12: labour force participation rate, state-wise

Jobs that India neads to create, state-wise, by 2027.

From: November 5, 2018: The Times of India

See graphic:

2011-12: India’s labour force participation rate, state-wise

Jobs that India neads to create, state-wise, by 2027.

Unemployment: The magnitude of the problem

2005-06> 2015-16: Sharp dip in Employment levels, particularly for women

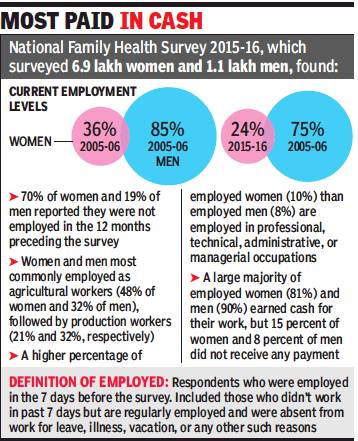

From: Rumu Banerjee, Sharp dip in employment levels in 2015-16: Survey, February 1, 2018: The Times of India

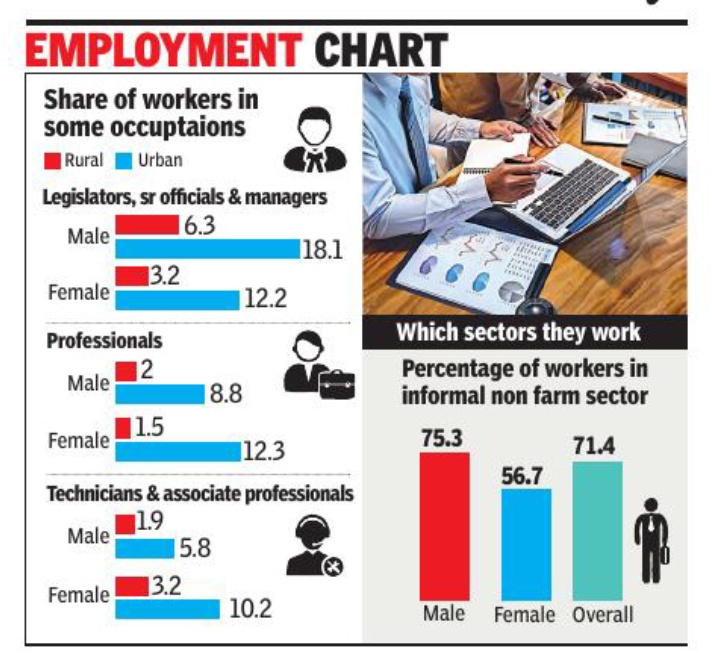

Employment levels, particularly for women, in 2015-16 as against 2005-06 have registered a sharp dip though women were employed in larger proportions than men in occupations such as “professional”, “technical”, “administrative” and “managerial”, the national family health survey has found.

A slightly higher percentage of women at 10% than men at 8% are employed in a professional, technical, administrative, or managerial occupations. Interestingly, 11% women who worked in past year were self employed.

Data collected by the survey shows employment levels have come down to 24% in 2015-16 for women, as compared to 36% in 2005-06. The figure is less stark for men but there is still a drop, with percentage currently employed down from 85% to 75% in the past decade.

The term ‘employed’ in the 2015-16 NFHS-4 is for respondents who were employed in the seven days before the survey. It included respondents who did not work in the past seven days but who are regularly employed and were absent from work for leave, illness, vacation, or any other reason.

“70% of women and 19% of men reported that they were not employed in the 12 months preceding the survey,” the survey said.

The survey found that men are three times as likely to be currently employed as women. The occupations have been categorised as professional, technical, administrative, managerial, clerical, sales and services, skilled manual, unskilled manual and agriculture.

Both women and men are most commonly employed as agricultural workers (48% of women and 32% of men), followed by production workers (21% and 32%, respectively).

A large majority of employed women (81%) and men (90%) earned cash for their work, but 15% of women and 8% of men did not receive any payment.

Jammu & Kashmir (14%), and Bihar and Assam (15% each) have the lowest percentage of women currently employed. More than one-third of women were currently employed in Manipur (41%), Telangana (39%), Meghalaya and Mizoram (35% each), and Andhra Pradesh (34%).

Amongst men, in the 15-19 years age group, 29.4% are currently employed, with 4.5% ‘not currently employed’. In the age group 20-24 years among men, 63.9% are employed. The percentage of unemployed goes down thereafter, ranging between 8.2% to 1.9% for 25-49 year old men.

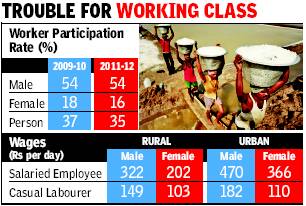

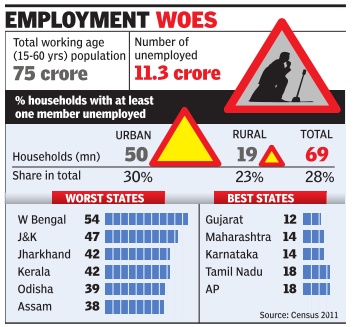

2009-12: Joblessness on rise

Non-NREGS work paying more: Govt survey

TIMES INSIGHT GROUP

Between 2009-2010 and 2011-2012, the proportion of people working slipped slightly in India, and the share of unemployed persons ticked up, a government report released on Thursday revealed. In 2009-10, 36.5% of the population was gainfully employed for the better part of the year. By 2011-12, the proportion of such workers had dipped to 35.4%. Meanwhile, the unemployment rate went up from 2.5% to 2.7%.

These findings form the crux of a survey on employment and unemployment carried out by the National Sample Survey Organization (NSSO). The survey covered over one lakh households and was carried out between July 2011 and June 2012. The pan-India figures hide a deepening chasm between job opportunities for men and women. While the share of employed men remained roughly constant between 2009 and 2011, women’s employment dropped from 18% to 16%.

Loss of jobs