Employment, unemployment: India

(→MNREGA) |

(→‘Poor investment in agriculture behind rural job dip’) |

||

| Line 191: | Line 191: | ||

[[Category:India|E]] | [[Category:India|E]] | ||

[[Category:Economy-Industry-Resources|E]] | [[Category:Economy-Industry-Resources|E]] | ||

| − | [[Category: | + | [[Category:Development|E]] |

[[Category:Name|Alphabet]] | [[Category:Name|Alphabet]] | ||

Revision as of 09:25, 14 July 2013

This is a collection of newspaper articles selected for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

2001-11: urban employment exceeds rural

For 1st time, urban areas pip villages in job creation

Subodh Varma TIMES INSIGHT GROUP

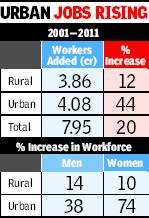

A fascinating, but worrying, picture of the way common Indians are earning their living emerges from recently released Census 2011 data. Urban areas have emerged as huge magnets for jobs, for the first time beating the rural hinterland in job creation in the past decade. Simultaneously, there is a rising dependence on short-term jobs, both in rural and urban areas, as regular full-term jobs fade away. The data also reveals huge differences in the kind of jobs men and women are getting. Clearly, India is going through a churning process, which will have far reaching effects on living standards, job related migration and gender relations.

More than half of the total 8 crore jobs created between 2001 and 2011 were located in urban areas, although the population staying in cities and towns is just a third of the total. This is a direct result of migration of people from unproductive farming in search of better prospects, supplemented by more areas getting defined as urban.

In the urban areas, women’s employment has seen a massive jump of over 74% since 2001, compared to just 38% for men. Women’s employment increased by over 1.2 crore in urban areas.

But the most significant feature is the creeping marginalization of jobs. Over 3 crore of the new jobs created in the past decade – 40% of the total – have been designated as ‘marginal’. This means that people work in these jobs for less than six months. A quarter of India’s 40-crore workforce is now subsisting on such marginal work.

While cultivation as the main occupation has declined by about 8% over the past decade, among marginal workers the picture is totally different. It has increased by 35% among male marginal workers, but declined by 20% among women. Seen in the context of the huge decline in main cultivators, it appears that men have been forced to work part time in their fields and part time either in others’ as agricultural labour or even in other kinds of work.

There appears to be a distinct shift towards what the census still persists in calling ‘other’ work – industry and services. And the vast bulk of these jobs are being created in cities and towns. Main workers in ‘other’ work jumped by 38% over the past decade compared to a measly 10% increase in rural areas. This is not surprising as most industries and service related jobs are located in urban or periurban areas (areas adjoining urban areas). Even here, the share of short- term workers in these ‘other’ jobs increased by a jaw dropping 84%.

2004-2010: Jobless growth?

‘Jobless growth’ during UPA-1, admits Centre

Self-Employed Dropped From 56.4% To 50.7% Of Workforce

Rajeev Deshpande TNN

New Delhi: Some 20 months after hotly contesting data on UPA-1’s “jobless growth”, the government has admitted to lack of substantial increase in employment between 2004-05 and 2009-2010, with the selfemployed workforce shrinking from 56.4% to 50.7% of the total workforce.

In absolute numbers, the self-employed decreased from 258.4 million to 232.7 million in this period while regular salaried workers rose from 69.7 million to 75.1 million. The ranks of casual labour rose from 129.7 million to 151.3 million. In all, the total workforce increased from 457.8 million to 459.1 million, a rise of just 0.3% over this period.

The ministry of planning has identified limited flexibility in “managing” the workforce, high cost of complying with labour regulations, poor skill development and a vast unorganized sector as reasons for dissatisfactory growth in employment.

Responding to Parliament’s finance standing committee’s query on why India was not creating enough productive jobs, the ministry said while the number of salaried employees increased, the selfemployed segment declined.

Interestingly, the ministry referred to the same 66th round of the National Sample Survey Organization that irked the government in June 2011 with Planning Commission deputy chairperson Montek Singh Ahluwalia slamming the report as inaccurate.

The controversy deeply embarrassed the ruling coalition as the data seemed to negate the Manmohan Singh government’s “inclusive growth” slogan despite policy initiatives intended to make growth less uneven.

Under official pressure, the NSSO later put down the employment statistics to factors like rising incomes resulting in women choosing to stay at home instead of taking up physically challenging jobs.

Yet , the planning ministry that has told the finance committee “India had an average growth rate of 7.9% in the 11th plan. However, this growth did not lead to increase in employment opportunities”.

Stating that the NSSO data exhibited a shift in employment status, the ministry said in the period 2004-05 to 2009-10, the percentage of regular salaried workers increased from 15.2% to 16.4% and there was a jump in casual labour from 28.3% to 33%. It indicates that informal employment that accompanies new real estate development, industry and urbanization has lagged.

This would include service providers like road side eateries, local transport, small shops and services like appliance repair.

The planning ministry did not explain the jump in casual labour but this could due to the rural employment guarantee scheme, although the government has also argued that the trend contradicts claims of slow employment.

The numbers may look even less flattering when the next bunch of statistics is available in view of the plummeting growth.

The government has listed measures like boosting manufacturing, developing skills, promoting labour intensive sectors and simplifying labour laws as an antidote to the employment logjam.

GOING SLOW

Percentage of self-employed dropped from 56.4% of total workforce in 2004-05 to 50.7% in 2009-10

Percentage of regular employees rose from 15.2 to 16.4 and of casual labourers from 28.3 to 33

In absolute numbers, number of self-employed was 258.4m in 2004-05 and 232.7m in 2009-10

There were 69.7m regular workers in 2004-05 and 75.1m in 2009-10

Casual labourers rose from 129.7m to 151.3m

Total workforce rose from 457.8m in 2004-05 to 459.1m in 2009-10, an increase of just 0.3% Casual labour grew from 28% to 33%

Job creation and the states

Poorer states take the lead in creating jobs

Subodh Varma | TIMES INSIGHT GROUP 2013/06/17

Most of the poorer, less industrialized states like Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh and Bihar appear to have done well in increasing their work force in the past decade according to recently released Census 2011 data. Surprisingly, richer or more urbanized states like Punjab, Haryana and Kerala have lagged far behind in job creation. But if you take away natural population growth, the picture changes dramatically.

It becomes clear that the workforce increase in the poorer states is mainly because of their higher than national aver- population growth. But again surprisingly, the richer states still remain at the bottom of job creation rankings. In terms of increase in total workers’ population, the top five states were Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, Rajasthan, Assam and Bihar, counting only major states, that is, those with over 2 crore population. The increase in their respective workforce was considerably higher than the national average. The states with the least increase over the past decade were Haryana, Punjab, Andhra Pradesh, Kerala and Gujarat.

UP, Bihar among states with least job creation

Since there is a natural growth in population, these figures do not give a correct picture of the changes in job opportunities in these states. Arough idea of what is the actual change in employment can be had by deducting the growth in population from the growth in workers. This reveals that Orissa, Assam, Kerala, Jharkhand and Rajasthan are the top five states in terms of job creation during 2001 and 2011.

While Orissa, Assam and Kerala appear to benefit from a much reduced population growth rate, Jharkhand and Rajasthan seem to have genuinely boosted jobs creation. After adjusting for population growth, the states with least job creation were Haryana, Punjab, Gujarat, Bihar and Uttar Pradesh. The latter two were hamstrung by still high population growth rates but the other three are laggards in job creation, reflecting stagnation and increased mechanization. These three also showed an absolute decline in the female workforce over 2001 and 2011. Census counts short term workers – those doing less than six months' work in a year – separately.

A look at how the cookie crumbles across the states in terms of short term work and longer term, more regular work throws up some bizarre results. While Maharashtra, Assam, Karnataka, Rajasthan and Gujarat created the most long term workers (‘main workers’), Bihar, Jharkhand, Punjab, West Bengal and Orissa added the least. On the other hand, short term, marginal workers increased by a jaw dropping 93% in Bihar, followed by Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, Orissa, UP. This is the fragile nature of job growth in states which may appear to be adding jobs in the past decade.

The rural-urban divide is starkly shown up in job creation, reflecting the doldrums that Indian agriculture is in. Across India, rural job growth was just 13% compared to 44% in urban areas. Some of the most agriculturally advanced states like Haryana and Punjab showed a decline in rural workforce while others like Andhra Pradesh and Gujarat had very small increases. The situation flips for urban areas where most states showed a healthy increase in the workforce. But Punjab, along with the two most urbanized states in the country, Tamil Nadu and Maharashtra, still remained at the bottom.

Unemployment, wages, NREGS

Joblessness on rise, non-NREGS work paying more: Govt survey

TIMES INSIGHT GROUP

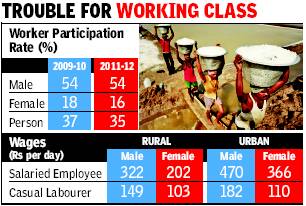

Between 2009-2010 and 2011-2012, the proportion of people working slipped slightly in India, and the share of unemployed persons ticked up, a government report released on Thursday revealed. In 2009-10, 36.5% of the population was gainfully employed for the better part of the year. By 2011-12, the proportion of such workers had dipped to 35.4%. Meanwhile, the unemployment rate went up from 2.5% to 2.7%.

These findings form the crux of a survey on employment and unemployment carried out by the National Sample Survey Organization (NSSO). The survey covered over one lakh households and was carried out between July 2011 and June 2012. The pan-India figures hide a deepening chasm between job opportunities for men and women. While the share of employed men remained roughly constant between 2009 and 2011, women’s employment dropped from 18% to 16%.

Loss of jobs

This may appear a small decline but translated into real numbers the crisis in employment is starkly revealed. In rural areas, about 90 lakh women lost their jobs in the two-year period. This would have been catastrophic but for the fact that in urban areas about 35 lakh women were added to the workforce.

Men joined the workforce in both urban and rural areas, though they got many more opportunities in towns and cities than in villages. Men’s participation in the workforce jumped from 99 million to 108 million in urban areas and from 228 million to 231 million in rural areas.

Unemployment

Kerala had the highest unemployment rate of close to 10% among the larger states. West Bengal (4.5%) and Assam (4.3%) were other large states with relatively high unemployment rates. Among smaller states, Nagaland had a staggering jobless rate of 27%, but this may be compromised data as surveys are difficult in strife-torn areas. Tripura too had a high unemployment rate of over 15%.

Wages

The report also contains striking information on daily wages of casual labourers and regular or salaried employees. In the government’s jobs scheme (MGNREGS), male workers were getting an average of Rs 112.46 per day, while in non-MGNREGS public works the rate was Rs 127.39, and in non-public works it was Rs 149.32. For women, the averages were more similar at about Rs 102 to Rs 110, though lower than men for the same work. This appears to go against a widely held belief that MGNREGS rates are setting the standard for all other wages in rural areas.

The wide gulf in urban and rural wage rates explains why people are migrating to live in cities. A male casual labourer earned about Rs 150 per day in rural areas, but his urban counterpart got Rs 180 per day. Similarly, a salaried employee could earn about Rs 300 per day in rural areas but in urban areas the same would shoot up to nearly Rs 450.

Rural wages, poverty, nutrition

2011-12: Rural wages rise, poverty declines, nutrition gets better

Rising rural wage may boost UPA’s chances

Swaminathan S Anklesaria Aiyar

The Times of India 2013/07/07

For all the current gloom about the economy, the 2011-12 data on employment and consumption shows a remarkable one-third increase in average household consumption over two years, well above the rate of inflation.

Four trends stand out. First, poverty is falling sharply. Second, wages are rising impressively. Third, people are shifting from cereals to superior foods. Fourth, contrary to popular perception, the employment guarantee scheme (MNREGA) has not been the key driver of higher wages.

Poverty ratio

The government has not yet provided a firm figure for the poverty ratio in 2011-12 compared with the last survey in 2009-10. But estimates from limited data suggest that the poverty ratio has fallen from 29.8% to just 24-26%. Earlier, poverty was falling by 0.75 % per year. This may have accelerated to 2% per year.

Wages

The most comprehensive consumption measure shows rural monthly spending per capita up from Rs 1,053 to Rs 1,430. For rural casual labour, other than in public works, male wages rose from Rs 102 to Rs 149, and female wages from Rs 69 to Rs 102. Urban trends were similar. Remarkably, casual wages grew faster than average national consumption: the poor fared disproportionately well. However, female wages grew more slowly than male wages.

Surprisingly, higher wages did not attract more people into the workforce. Over the two years, the male rural workforce increased by only 2.7 million, while the female rural workforce actually declined by 2.7 million. The unemployment rate rose slightly from 2.0% to 2.2%, but both rates are very low. The biggest problem is not lack of jobs but lack of workers. The optimistic explanation is that millions of youngsters have chosen to study instead of working. The pessimistic explanation is that women find work conditions unsafe or unsuitable.

Are machines causing unemployment?

Some analysts fear that rural women are being displaced by growing mechanization. Punjab farmers are switching to mechanical rice transplanters, and combine harvesters are spreading even in Bihar. But rural wages are rising sharply, contradicting the theory that machines are causing unemployment. Rather, the scarcity of labour is forcing farmers to mechanize. We need more research to explain the abysmally low participation of women in the workforce, down from almost 30% in 2004 to just 22% today.

Female participation

In urban areas, female participation is a pathetic 15%. For this to happen at a time of sharply rising wages — which should normally attract more women to work — is a huge unsolved puzzle. MNREGA is targeted at women, yet rural female participation has plummeted.

Food consumption patterns

Food consumption patterns have been changing dramatically. Between 1993-94 and 2011-12, the share of cereals in consumption halved from 24.2% to 12% in rural areas, and from 14% to 7.3% in urban areas. The share of non-food items shot up from 36.8% to 51.4% in rural areas, showing growing prosperity. Rural folk have shifted to superior foods. What’s up is the share of beverages, eggs, fish, meat, fruit and nuts.

Clearly, Indians as a whole have more than enough cereals and are moving to superior foods and consumer durables and services. The shift is evident in all income groups. The Food Security Bill aims to expand subsidized cereal supply from 40% of the population to 67%. Clearly this is a middle-class giveaway, unrelated to food security.

In 2004, only 2% of Indians said they were hungry any time of year. These are the people needing food security, not the middle-class. However, while hunger is limited, malnutrition is widespread. People need additional iron, vitamins and proteins. But the Food Security Bill targets only cereals.

MNREGA

In its initial years, MNREGA typically paid higher wages than the minimum wage. Indeed, many states raised their minimum wage rate sharply on finding that the Centre would foot the MNREGA bill.

Earlier, when states raised the minimum wage for political reasons, market rates did not move at all. Farmers dismissed the minimum wage as a gimmick. But today, market rates for casual labour have risen well above MNREGA rates. In 2011-12, MNREGA paid on average Rs 112 to males and Rs 102 to females. This was well below the open market rural wage of Rs 149 per days for males, and marginally below the rate of Rs 103 for females. The main reason seems to be fast GDP growth for a decade. All Asian miracle economies achieved rising wages through fast GDP growth, not employment schemes. India seems no different.

The employment of women: 2009-12

Rural women lost 9.1m jobs in 2 yrs, urban gained 3.5m

Not Getting Long-Term Work: Survey

Subodh Varma TIMES INSIGHT GROUP

Women’s employment has taken an alarming dip in rural areas in the past two years, a government survey has revealed. In jobs that are done for ‘the major part of the year’, a staggering 9.1 million jobs were lost by rural women. In urban areas, the situation was quite the reverse, with over 3.5 million women added to the workforce.

This emerges from comparing employment data of two consecutive surveys conducted by the National Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO) in 2009-10 and 2011-12. Key results of the later survey were released last month. Both rounds had a large sample size of nearly 4.5 lakh people.

“The survey shows that in the continuing employment crunch in rural areas, the most vulnerable sections — like the women — are getting eliminated,” says Amitabh Kundu, professor of economics at Jawaharlal Nehru University.

If subsidiary work, that is short-term, supplementary work is also counted, women’s employment numbers improve, but they still show a huge decline of 2.7 million in two years. This is a reflection of the fact that women are no longer getting longer-term, or principal, and better paying jobs, and so are forced to take up short-term transient work.

Declining women’s employment in rural areas is a long-term trend in India despite high economic “growth”, says Neetha N of the Centre for Women’s Development Studies.

“Three decades ago, in 1983, about 34% of women in rural areas were working. This has steadily declined and now stands at just short of 25%. But the decline in the past two years is shocking – it is the most drastic decline we have ever seen,” she says.

‘Poor investment in agriculture behind rural job dip’

Many argue that decline in women’s work is taking place because more women are now either studying or just staying home because the men of the family are earning enough. However,this is not supported by the data, according to Neetha. “Urban areas have more girls’ enrolment in schools and colleges, and better household incomes than rural areas. Yet women’s employment is increasing in urban areas and declining in rural areas,” she points out.

But what is the reason behind this jobs crisis in rural India? “A decline in public investment in agriculture, and in extension work for dissemination of knowledge coupled with increasing mechanization are the main causes of this crisis of jobs,” says V K Ramachandran, professor of economic analysis at the Indian Statistical Institute, Bangalore. He also blames the severe slowdown in expansion of irrigation and supply of electricity to rural areas for causing jobs to dry up.

Satya Narain Singh, deputy director general of NSSO, told TOI that there were no issues of measurement or sample size in the surveys. He pointed out that the population for 2010 was based on Census projections while that for 2012 was based on actual Census 2011 data. This could introduce a small over-estimation of the 2010 population. But the “decline in female workforce is in line with the trend of decline observed in recent decades”, Singh said.