Employment, unemployment: India

Contents |

Add Title/Subtitle

Title and authorship of the original article(s)

|

Add title of article By Add author, Add source, Add date in format(MM,DD,YYYY) |

This is a newspaper article selected for the excellence of its content. |

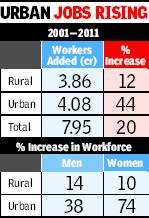

2001-11: urban employment exceeds rural

For 1st time, urban areas pip villages in job creation

Subodh Varma TIMES INSIGHT GROUP

A fascinating, but worrying, picture of the way common Indians are earning their living emerges from recently released Census 2011 data. Urban areas have emerged as huge magnets for jobs, for the first time beating the rural hinterland in job creation in the past decade. Simultaneously, there is a rising dependence on short-term jobs, both in rural and urban areas, as regular full-term jobs fade away. The data also reveals huge differences in the kind of jobs men and women are getting. Clearly, India is going through a churning process, which will have far reaching effects on living standards, job related migration and gender relations.

More than half of the total 8 crore jobs created between 2001 and 2011 were located in urban areas, although the population staying in cities and towns is just a third of the total. This is a direct result of migration of people from unproductive farming in search of better prospects, supplemented by more areas getting defined as urban.

In the urban areas, women’s employment has seen a massive jump of over 74% since 2001, compared to just 38% for men. Women’s employment increased by over 1.2 crore in urban areas.

But the most significant feature is the creeping marginalization of jobs. Over 3 crore of the new jobs created in the past decade – 40% of the total – have been designated as ‘marginal’. This means that people work in these jobs for less than six months. A quarter of India’s 40-crore workforce is now subsisting on such marginal work.

While cultivation as the main occupation has declined by about 8% over the past decade, among marginal workers the picture is totally different. It has increased by 35% among male marginal workers, but declined by 20% among women. Seen in the context of the huge decline in main cultivators, it appears that men have been forced to work part time in their fields and part time either in others’ as agricultural labour or even in other kinds of work.

There appears to be a distinct shift towards what the census still persists in calling ‘other’ work – industry and services. And the vast bulk of these jobs are being created in cities and towns. Main workers in ‘other’ work jumped by 38% over the past decade compared to a measly 10% increase in rural areas. This is not surprising as most industries and service related jobs are located in urban or periurban areas (areas adjoining urban areas). Even here, the share of short- term workers in these ‘other’ jobs increased by a jaw dropping 84%.

2004-2010: Jobless growth?

‘Jobless growth’ during UPA-1, admits Centre

Self-Employed Dropped From 56.4% To 50.7% Of Workforce

Rajeev Deshpande TNN

New Delhi: Some 20 months after hotly contesting data on UPA-1’s “jobless growth”, the government has admitted to lack of substantial increase in employment between 2004-05 and 2009-2010, with the selfemployed workforce shrinking from 56.4% to 50.7% of the total workforce.

In absolute numbers, the self-employed decreased from 258.4 million to 232.7 million in this period while regular salaried workers rose from 69.7 million to 75.1 million. The ranks of casual labour rose from 129.7 million to 151.3 million. In all, the total workforce increased from 457.8 million to 459.1 million, a rise of just 0.3% over this period.

The ministry of planning has identified limited flexibility in “managing” the workforce, high cost of complying with labour regulations, poor skill development and a vast unorganized sector as reasons for dissatisfactory growth in employment.

Responding to Parliament’s finance standing committee’s query on why India was not creating enough productive jobs, the ministry said while the number of salaried employees increased, the selfemployed segment declined.

Interestingly, the ministry referred to the same 66th round of the National Sample Survey Organization that irked the government in June 2011 with Planning Commission deputy chairperson Montek Singh Ahluwalia slamming the report as inaccurate.

The controversy deeply embarrassed the ruling coalition as the data seemed to negate the Manmohan Singh government’s “inclusive growth” slogan despite policy initiatives intended to make growth less uneven.

Under official pressure, the NSSO later put down the employment statistics to factors like rising incomes resulting in women choosing to stay at home instead of taking up physically challenging jobs.

Yet , the planning ministry that has told the finance committee “India had an average growth rate of 7.9% in the 11th plan. However, this growth did not lead to increase in employment opportunities”.

Stating that the NSSO data exhibited a shift in employment status, the ministry said in the period 2004-05 to 2009-10, the percentage of regular salaried workers increased from 15.2% to 16.4% and there was a jump in casual labour from 28.3% to 33%. It indicates that informal employment that accompanies new real estate development, industry and urbanization has lagged.

This would include service providers like road side eateries, local transport, small shops and services like appliance repair.

The planning ministry did not explain the jump in casual labour but this could due to the rural employment guarantee scheme, although the government has also argued that the trend contradicts claims of slow employment.

The numbers may look even less flattering when the next bunch of statistics is available in view of the plummeting growth.

The government has listed measures like boosting manufacturing, developing skills, promoting labour intensive sectors and simplifying labour laws as an antidote to the employment logjam.

GOING SLOW

Percentage of self-employed dropped from 56.4% of total workforce in 2004-05 to 50.7% in 2009-10

Percentage of regular employees rose from 15.2 to 16.4 and of casual labourers from 28.3 to 33

In absolute numbers, number of self-employed was 258.4m in 2004-05 and 232.7m in 2009-10

There were 69.7m regular workers in 2004-05 and 75.1m in 2009-10

Casual labourers rose from 129.7m to 151.3m

Total workforce rose from 457.8m in 2004-05 to 459.1m in 2009-10, an increase of just 0.3% Casual labour grew from 28% to 33%

Job creation and the states

Poorer states take the lead in creating jobs

Subodh Varma | TIMES INSIGHT GROUP 2013/06/17

Most of the poorer, less industrialized states like Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh and Bihar appear to have done well in increasing their work force in the past decade according to recently released Census 2011 data. Surprisingly, richer or more urbanized states like Punjab, Haryana and Kerala have lagged far behind in job creation. But if you take away natural population growth, the picture changes dramatically.

It becomes clear that the workforce increase in the poorer states is mainly because of their higher than national aver- population growth. But again surprisingly, the richer states still remain at the bottom of job creation rankings. In terms of increase in total workers’ population, the top five states were Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, Rajasthan, Assam and Bihar, counting only major states, that is, those with over 2 crore population. The increase in their respective workforce was considerably higher than the national average. The states with the least increase over the past decade were Haryana, Punjab, Andhra Pradesh, Kerala and Gujarat.

UP, Bihar among states with least job creation

Since there is a natural growth in population, these figures do not give a correct picture of the changes in job opportunities in these states. Arough idea of what is the actual change in employment can be had by deducting the growth in population from the growth in workers. This reveals that Orissa, Assam, Kerala, Jharkhand and Rajasthan are the top five states in terms of job creation during 2001 and 2011.

While Orissa, Assam and Kerala appear to benefit from a much reduced population growth rate, Jharkhand and Rajasthan seem to have genuinely boosted jobs creation. After adjusting for population growth, the states with least job creation were Haryana, Punjab, Gujarat, Bihar and Uttar Pradesh. The latter two were hamstrung by still high population growth rates but the other three are laggards in job creation, reflecting stagnation and increased mechanization. These three also showed an absolute decline in the female workforce over 2001 and 2011. Census counts short term workers – those doing less than six months' work in a year – separately.

A look at how the cookie crumbles across the states in terms of short term work and longer term, more regular work throws up some bizarre results. While Maharashtra, Assam, Karnataka, Rajasthan and Gujarat created the most long term workers (‘main workers’), Bihar, Jharkhand, Punjab, West Bengal and Orissa added the least. On the other hand, short term, marginal workers increased by a jaw dropping 93% in Bihar, followed by Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, Orissa, UP. This is the fragile nature of job growth in states which may appear to be adding jobs in the past decade.

The rural-urban divide is starkly shown up in job creation, reflecting the doldrums that Indian agriculture is in. Across India, rural job growth was just 13% compared to 44% in urban areas. Some of the most agriculturally advanced states like Haryana and Punjab showed a decline in rural workforce while others like Andhra Pradesh and Gujarat had very small increases. The situation flips for urban areas where most states showed a healthy increase in the workforce. But Punjab, along with the two most urbanized states in the country, Tamil Nadu and Maharashtra, still remained at the bottom.