Employment, unemployment: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content.

|

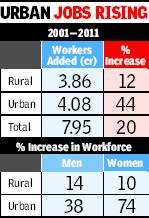

2001-11: urban employment exceeds rural

For 1st time, urban areas pip villages in job creation

Subodh Varma TIMES INSIGHT GROUP

A fascinating, but worrying, picture of the way common Indians are earning their living emerges from recently released Census 2011 data. Urban areas have emerged as huge magnets for jobs, for the first time beating the rural hinterland in job creation in the past decade. Simultaneously, there is a rising dependence on short-term jobs, both in rural and urban areas, as regular full-term jobs fade away. The data also reveals huge differences in the kind of jobs men and women are getting. Clearly, India is going through a churning process, which will have far reaching effects on living standards, job related migration and gender relations.

More than half of the total 8 crore jobs created between 2001 and 2011 were located in urban areas, although the population staying in cities and towns is just a third of the total. This is a direct result of migration of people from unproductive farming in search of better prospects, supplemented by more areas getting defined as urban.

In the urban areas, women’s employment has seen a massive jump of over 74% since 2001, compared to just 38% for men. Women’s employment increased by over 1.2 crore in urban areas.

But the most significant feature is the creeping marginalization of jobs. Over 3 crore of the new jobs created in the past decade – 40% of the total – have been designated as ‘marginal’. This means that people work in these jobs for less than six months. A quarter of India’s 40-crore workforce is now subsisting on such marginal work.

While cultivation as the main occupation has declined by about 8% over the past decade, among marginal workers the picture is totally different. It has increased by 35% among male marginal workers, but declined by 20% among women. Seen in the context of the huge decline in main cultivators, it appears that men have been forced to work part time in their fields and part time either in others’ as agricultural labour or even in other kinds of work.

There appears to be a distinct shift towards what the census still persists in calling ‘other’ work – industry and services. And the vast bulk of these jobs are being created in cities and towns. Main workers in ‘other’ work jumped by 38% over the past decade compared to a measly 10% increase in rural areas. This is not surprising as most industries and service related jobs are located in urban or periurban areas (areas adjoining urban areas). Even here, the share of short- term workers in these ‘other’ jobs increased by a jaw dropping 84%.

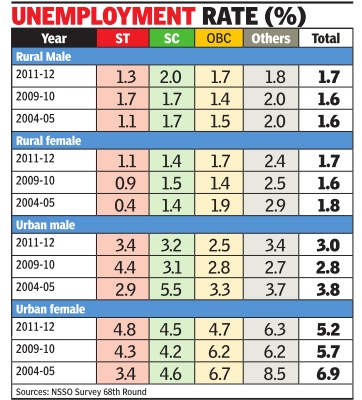

Unemployment rate: area, category and gender-wise

Apr 25 2015

Ranks of jobless SCs, OBCs in villages swell

Mahendra Singh

Unemployment increased, if marginally , among rural male inhabitants of the scheduled castes (SC) and other backwards castes (OBC) between 2009-10 and 2011-12, a survey by the National Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO) has discovered. In this period, the unemployment rate for men living in villages went up from 1.7% to 2% among SCs, and from 1.4% to 1.7% among OBCs.The unemployment rate decreased marginally , from 1.7% to nearly 1.3%, for STs, and 2% to 1.8% for those who comprise `Others' category.

Among women living in rural areas, the unemployment rate for STs increased from 0.9% in 2009-10 to 1.1% in 2011-12, and for OBCs, from 1.4% to 1.7%. It remained almost at the same level for SCs (1.5% in 2009-10 compared to 1.4% in 2011-12) and `Others' (2.5% in 2009-10 compared to 2.4% in 2011-12). In cities and towns, the unemployment rate among men decreased for STs (from 4.4% in 2009-10 to 3.4% in 2011-12) and OBCs (from 2.8% to 2.5% for the period) while remaining at the same level for SCs (3.1% in 2009-10 to 3.2% in 2011-12). The unemployment rate for `Others', however, increased from 2.7% to 3.4%.

Unemployment has increased among ST and SC women living in urban areas, going up from 4.3% in 2009-10 to 4.8% in 2011-12 for STs, and from 4.2% to 4.5% for SCs.However, unemployment decreased among OBC women living in cities and towns (from 6.2% to 4.7%) and remained at the same level for `Others' (6.2% in 2009-10 and 6.3% in 2011-12). In a nutshell, the unemployment rate in 2011-12 for urban women was lowest among SCs, while their ST counterparts were better placed in villages. Among males living in urban areas, unemployment was worst for STs, while SCs faced the highest rate in villages.

2004-2010

2004-2010: Jobless growth?

‘Jobless growth’ during UPA-1, admits Centre

Self-Employed Dropped From 56.4% To 50.7% Of Workforce

Rajeev Deshpande TNN

New Delhi: Some 20 months after hotly contesting data on UPA-1’s “jobless growth”, the government has admitted to lack of substantial increase in employment between 2004-05 and 2009-2010, with the selfemployed workforce shrinking from 56.4% to 50.7% of the total workforce.

In absolute numbers, the self-employed decreased from 258.4 million to 232.7 million in this period while regular salaried workers rose from 69.7 million to 75.1 million. The ranks of casual labour rose from 129.7 million to 151.3 million. In all, the total workforce increased from 457.8 million to 459.1 million, a rise of just 0.3% over this period.

The ministry of planning has identified limited flexibility in “managing” the workforce, high cost of complying with labour regulations, poor skill development and a vast unorganized sector as reasons for dissatisfactory growth in employment.

Responding to Parliament’s finance standing committee’s query on why India was not creating enough productive jobs, the ministry said while the number of salaried employees increased, the selfemployed segment declined.

Interestingly, the ministry referred to the same 66th round of the National Sample Survey Organization that irked the government in June 2011 with Planning Commission deputy chairperson Montek Singh Ahluwalia slamming the report as inaccurate.

The controversy deeply embarrassed the ruling coalition as the data seemed to negate the Manmohan Singh government’s “inclusive growth” slogan despite policy initiatives intended to make growth less uneven.

Under official pressure, the NSSO later put down the employment statistics to factors like rising incomes resulting in women choosing to stay at home instead of taking up physically challenging jobs.

Yet , the planning ministry that has told the finance committee “India had an average growth rate of 7.9% in the 11th plan. However, this growth did not lead to increase in employment opportunities”.

Stating that the NSSO data exhibited a shift in employment status, the ministry said in the period 2004-05 to 2009-10, the percentage of regular salaried workers increased from 15.2% to 16.4% and there was a jump in casual labour from 28.3% to 33%. It indicates that informal employment that accompanies new real estate development, industry and urbanization has lagged.

This would include service providers like road side eateries, local transport, small shops and services like appliance repair.

The planning ministry did not explain the jump in casual labour but this could due to the rural employment guarantee scheme, although the government has also argued that the trend contradicts claims of slow employment.

The numbers may look even less flattering when the next bunch of statistics is available in view of the plummeting growth.

The government has listed measures like boosting manufacturing, developing skills, promoting labour intensive sectors and simplifying labour laws as an antidote to the employment logjam.

GOING SLOW

Percentage of self-employed dropped from 56.4% of total workforce in 2004-05 to 50.7% in 2009-10

Percentage of regular employees rose from 15.2 to 16.4 and of casual labourers from 28.3 to 33

In absolute numbers, number of self-employed was 258.4m in 2004-05 and 232.7m in 2009-10

There were 69.7m regular workers in 2004-05 and 75.1m in 2009-10

Casual labourers rose from 129.7m to 151.3m

Total workforce rose from 457.8m in 2004-05 to 459.1m in 2009-10, an increase of just 0.3% Casual labour grew from 28% to 33%

2004-10: Fifty lakh jobs lost?

The Times of India, Aug 23, 2015

5 million jobs lost during high-growth years, says study

As many as five million jobs were lost between 2004-05 and 2009-10 — paradoxically during the time when India's economy grew at a fast clip — an Assocham study said.

This has put a question mark on whether economic expansion should be linked to job creation, according to the study.

Moreover, it observed that over-emphasis on services and neglect of the manufacturing sector are mainly responsible for this "jobless growth" phenomenon. Even as about 13 million youth are entering labour force every year, the gap between employment and growth widened during the period, the study noted.

"The Indian economy went through a period of jobless growth when five million jobs were lost between 2004-05 and 2009-10 while the economy was growing at an impressive rate," Assocham said.

Quoting Census data, it said the number of people seeking jobs grew annually at 2.23 per cent between 2001 and 2011, but growth in actual employment during the same period was only 1.4 per cent.

"This large workforce needs to be productively engaged to avoid socio-economic conflicts," Assocham secretary general D S Rawat said.

The changing demographic patterns, he said, suggest that today's youth is better educated, probably more skilled than the previous generation and highly aspirational.

"In a service-driven economy, which contributed 67.3 per cent (at constant price) to GDP but employed only 27 per cent of total workforce in 2013-14, enough jobs will not be created to absorb the burgeoning workforce," Assocham added.

Experts argue that the growth of manufacturing will be key for growth in income and employment for multiple reasons. For every job created in the manufacturing sector, three additional jobs are created in related activities.

In 2013-14, manufacturing contributed 15 per cent to GDP and employed about the same percentage of total workforce, a sign that the sector has a better labour absorption compared with services.

Employment level, women

The Indian Express , July 26, 2016

Since 2005, fewer jobs for women in India

In rural areas, female labour force participation among women aged 15 years and above has fallen from 49% in 2005 to 36% in 2012. More than half of the decline is due to the scarcity of suitable jobs at the local level.

Female labour force participation in India is among the lowest in the world. What’s worse, the share of working women in India is declining. This is a cause for concern since higher labour earnings are the primary driver of poverty reduction. It is often argued that declining female participation is due to rising incomes that allow more women to stay at home. The evidence, however, shows that after farming jobs collapsed post 2005, alternative jobs considered suitable for women failed to replace them.

Rising labour earnings have been the main force behind India’s remarkable decline in poverty. The gains arise partly from the demographic transition, which increases the share of working members in the average family. But trends in female labour force participation veer in the opposite direction. Today, India has one of the lowest female participation rates in the world, ranking 120th among the 131 countries for which data are available. Even among countries with similar income levels, India is at the bottom, together with Yemen, Pakistan and Egypt (Figure 1). Worse still, the rate has been declining since 2005. This is a matter of concern as women’s paid employment is known to increase their ability to influence decision-making within the household, and empower them more broadly in society as a whole.

This declining trend has been particularly pronounced in rural areas, where female labour force participation among women aged 15 years and above fell from 49% in 2005 to 36% in 2012. This is the most recent period for which data are available. The numbers are based on the National Sample Survey’s (NSS) definition of ‘usual status’ of work, but the trend remains similar with other definitions too. In a recent paper, we argue that the explanation for this disturbing trend is the lack of suitable job opportunities for women. In a traditional society like India, where women bear the bulk of the responsibility for domestic chores and child care, their work outside the home is acceptable if it takes place in an environment that is perceived as safe, and allows the flexibility of multi-tasking. Indeed, three-quarters of women who were willing to work, if work was made available, favoured part-time salaried jobs. From this perspective, female labour force participation can be expected to depend on the availability of ‘suitable jobs’ such as farming, which are both flexible and close to home. However, the number of farming jobs has been shrinking, without a commensurate increase in other employment opportunities. Our research suggests that more than half of the decline in female labour force participation is due to the scarcity of suitable jobs at the local level. d A large body of academic work in India has focused on a different explanation, the so-called “income effect”. It is argued that higher household incomes have gradually allowed more rural women to stay at home, and that this is a preferred household choice in a predominantly patriarchal society. Other frequently-mentioned explanations are that the share of working women is declining because girls are staying longer in school. It is also said that with shrinking family sizes, and without the back-up of institutional child support, women have no option but to stay out of the work force. We are sceptical. Staying longer in school and being less able to rely on family support for child-rearing could justify a decline in participation rates among younger women, but not the equally important drop among middle-aged cohorts. There are also reasons to downplay the income effect. Between 2005 and 2012 India experienced roughly a doubling of wages in real terms. But across districts, a doubling of real wages is associated with a 3 percentage point decline in female participation rates, not with the much larger 13 percentage point fall that actually occurred. Our research shows that these factors explain less than a quarter of the recent decline in India’s female labour force participation. sdf Evidence also points to a less ‘voluntary’ withdrawal of women from the labour force than the income effect explanation implies. The NSS, which is the main source of labour market data, tends to underestimate women’s work. What most working women do in India does not match the image of a regular, salaried, 9-to-5 job. Many women have marginal jobs or are engaged in multiple activities, including home production, which is often hard to measure well. Female unemployment may be underestimated as well. If one were to relax the stringent criteria used by the NSS to define labour force participation, and include the women who participated under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA), or were registered with a placement agency, then the female labour force participation rate would be between 3 and 5 percentage points higher. This measurement problem is further evidenced by the population census data that report much higher rates of female unemployment than the NSS. Beyond the income effect and measurement issues, the main driver of the decline in female labour force participation rates is the transformation of job opportunities at the local level. After 2005, farming jobs collapsed, especially in small villages, and alternative job opportunities considered suitable for women failed to replace them. Regular, non-farm employment only expanded in large cities (Figure 2). As a result, there is a ‘valley’ of suitable jobs along the rural-urban gradation. Fortunately, the decline in female labour force participation is not irreversible. The trend can be turned around through a more vibrant creation of local salaried jobs — including part-time jobs — in the intermediate range of the rural-urban gradation where an increasingly large share of the Indian population now resides.

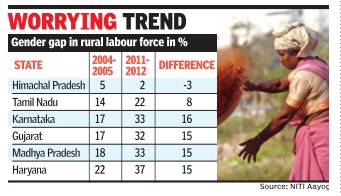

2004-2012:Women as rural labour

The Times of India Jan 11 2016

B Sivakumar

Chennai Women in rural areas are increasingly withdrawing from the country's labour force. This trend is particularly evident in states like Karnataka, Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh where women have opted out of the labour force over the years. It is also quite strong in the southern state of Tamil Nadu, where the difference in gender gap between 2004 and 2011 is 8%. In Karnataka, it is 16, while in Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh it is 15. The higher the gender gap the lower the female participation in labour force.

According to a study conducted by Niti Aayog, the main reasons are lack of job opportunities for women in rural areas and the poor performance in the agriculture sector. Due to the fall in number of women in the labour force, the gender gap has increased to 25 percentage points in India between 2005 and 2011.

“Women who lost jobs in agriculture did not find place in other sectors of the economy . One of the reasons is the poor education of rural women that acts as a barrier to a smooth inter-sectoral labour mobility . Nearly 69% of rural women are either illiterate or have been educated only up to the primary level,“ said the study done by Sunita Sanghi, A Srija and Shirke Shrinivas Vijay of NitiAayog.

“While there is a rise in real wages of women labour force after introduction of MGNREGS, younger women in the school and college going ages are migrating to towns for education. It is only the older women, who have lost employment opportunities,“ said said Madras Institute of Development Studies professor D Jayaraj.

2014

Employment rate of Indians hits record high

The Times of India, Nov 02 2015

Kounteya Sinha

Employment rate of Indians in Britain hits record high

The employment rate of the Indian community reached a record high at 71.6% in Britain in 2014 . The employment rate of Pakistanis and Bangladeshis jointly was only 51%, while that of the Chinese was 56%.

This means 784,000 Indian people were at work in Britain, an increase of 32,000 from the previous year and 238,000 more since 2005. Of these, over 100,000 people from the Indian community run their own businesses in the UK.

As against Indians, only 560,000 Pakistanis and Bang ladeshis held jobs in 2014, while the number was as low as 135,000 among Britain's Chinese community .

The rate at which Indians in the UK are getting jobs has left all other ethnic minority groups behind. In 2006, 600,000 Indians aged 16 years and over were employed.

The number increased to 638,000 in 2008, 671,000 in 2009 and 692,000 in 2010. In 2011, it was 712,000 which rose to 752,000 in 2013.

Indians in UK were also recently found to be the most prosperous among all minority groups.

High growth and job creation

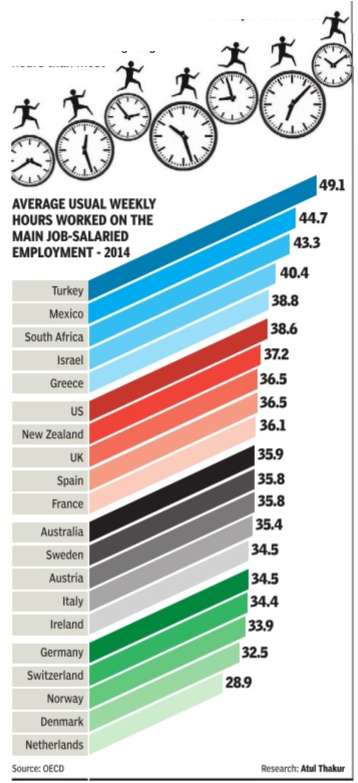

LIVELIHOODS - High growth not enough for job creation

Atul Thakur The Times of India Sep 23 2014

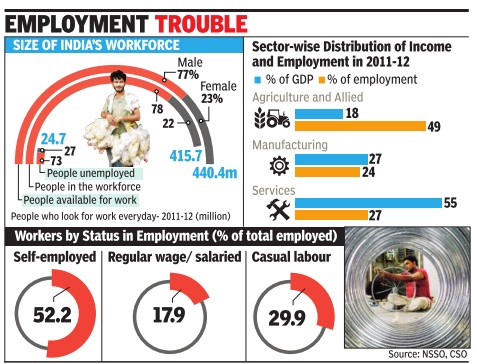

Rapid increase in the GDP has not ensured that jobs are created just as fast. The quality of employment also remains a matter of concern

After years of low growth, the In dian economy is showing signs of recovery . But the big ques tion remains -will a return to high growth, if that happens, also mean rapid job creation?

Data suggests this does not follow automatically. Between 2004-05 and 2009-10, a period that saw three successive years of 9%-plus growth, data from the National Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO) showed virtually no growth in employment. Jobless growth is a real threat. The NSSO survey indicates that India's labour force was between 440 million to 484 million in 2011-12. The lower number indicates people who looked for work every day, while the higher points to those who joined the workforce at some point in the year. The data shows that 416 million of the 440 million who looked for work on a daily basis were employed at the time of the sur vey, meaning about 25 million remained unemployed.

Even what employment is available tends to be of low quality. In 2011-12, NSSO data shows, only 18% of working people had regular wagesalary employment.Roughly 30% were casual labourers, dependent on daily or periodic renewal of job opportunities. The remaining 52% were self-employed. Most of them were in agriculture, working as helpers in familyowned businesses without salary .

Much of the workforce in advanced economies is employed on regular wage salary. In the US, UK, Japan and Germany , roughly 90% of the workforce are regular wagesalary earners. World Bank's World Development Report, 2014, shows that the average proportion of people with regular wage employment in India's workforce was 17% during 2001-10. This was only 2% higher than in the previous decade.Evidently , the benefits of high GDP growth haven't helped most workers.

Estimates on employment in organised and unorganised sectors confirm India's dire situation. The unorganised workers social security act, 2008, defines unorganised workers as those who are home-based, self-employed or are wage workers in the organised sector not covered under labour welfare acts. This category is estimated to constitute more than 90% of the workforce.

As for the self-employed, there's reason to believe this category has a large element of disguised unemployment. This becomes clearer when we see the sector-wise employment and income patterns. In 2011-12, agri culture, forestry and fishing contributed 18% to overall GDP but employed 49% of the workforce. The secondary sector ¬ manufacturing, mining, electricity and construction ¬ had a share of 27% in GDP and 24% in employment. Services, dubbed engine of India's GDP growth, accounted for 55% of the total national output but employed a meagre 27% of the workforce. . Much of the `employment' in agricul ture -or even in small self-owned shops -is as a fallback in a distress situation in which jobs are not available and the absence of a social security net means the poor cannot afford to be unemployed. Rural job guarantee scheme NREGA , signalled a recognition of this reality and sought to provide relief.

However, it has not been able to provide work for the promised 100 days a year to most households. In 2013. 14, only 9% of households who sought it could get work for 100 days. The average was 43 days per household. The scheme focuses on unskilled work. The problem of skill development enabling labour migration to services remains inadequately addressed. India's employment crisis is marred by social issues which don't allow women to join the labour force. While over 55% of men was available in the labour force at some time in the year, according to NSSO, only 22% of women were available for work. That women are often paid lower wages than men for doing the same work does not help gender parity, either.

Job creation and the states

Poorer states take the lead in creating jobs

Subodh Varma | TIMES INSIGHT GROUP 2013/06/17

Most of the poorer, less industrialized states like Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh and Bihar appear to have done well in increasing their work force in the past decade according to recently released Census 2011 data. Surprisingly, richer or more urbanized states like Punjab, Haryana and Kerala have lagged far behind in job creation. But if you take away natural population growth, the picture changes dramatically.

It becomes clear that the workforce increase in the poorer states is mainly because of their higher than national aver- population growth. But again surprisingly, the richer states still remain at the bottom of job creation rankings. In terms of increase in total workers’ population, the top five states were Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, Rajasthan, Assam and Bihar, counting only major states, that is, those with over 2 crore population. The increase in their respective workforce was considerably higher than the national average. The states with the least increase over the past decade were Haryana, Punjab, Andhra Pradesh, Kerala and Gujarat.

UP, Bihar: least job creation

Since there is a natural growth in population, these figures do not give a correct picture of the changes in job opportunities in these states. Arough idea of what is the actual change in employment can be had by deducting the growth in population from the growth in workers. This reveals that Orissa, Assam, Kerala, Jharkhand and Rajasthan are the top five states in terms of job creation during 2001 and 2011.

While Orissa, Assam and Kerala appear to benefit from a much reduced population growth rate, Jharkhand and Rajasthan seem to have genuinely boosted jobs creation. After adjusting for population growth, the states with least job creation were Haryana, Punjab, Gujarat, Bihar and Uttar Pradesh. The latter two were hamstrung by still high population growth rates but the other three are laggards in job creation, reflecting stagnation and increased mechanization. These three also showed an absolute decline in the female workforce over 2001 and 2011. Census counts short term workers – those doing less than six months' work in a year – separately.

A look at how the cookie crumbles across the states in terms of short term work and longer term, more regular work throws up some bizarre results. While Maharashtra, Assam, Karnataka, Rajasthan and Gujarat created the most long term workers (‘main workers’), Bihar, Jharkhand, Punjab, West Bengal and Orissa added the least. On the other hand, short term, marginal workers increased by a jaw dropping 93% in Bihar, followed by Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, Orissa, UP. This is the fragile nature of job growth in states which may appear to be adding jobs in the past decade.

The rural-urban divide is starkly shown up in job creation, reflecting the doldrums that Indian agriculture is in. Across India, rural job growth was just 13% compared to 44% in urban areas. Some of the most agriculturally advanced states like Haryana and Punjab showed a decline in rural workforce while others like Andhra Pradesh and Gujarat had very small increases. The situation flips for urban areas where most states showed a healthy increase in the workforce. But Punjab, along with the two most urbanized states in the country, Tamil Nadu and Maharashtra, still remained at the bottom.

Unemployment, wages, NREGS

Joblessness on rise

Non-NREGS work paying more: Govt survey

TIMES INSIGHT GROUP

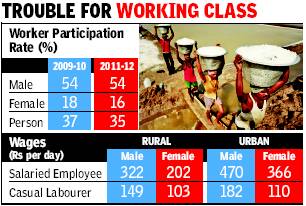

Between 2009-2010 and 2011-2012, the proportion of people working slipped slightly in India, and the share of unemployed persons ticked up, a government report released on Thursday revealed. In 2009-10, 36.5% of the population was gainfully employed for the better part of the year. By 2011-12, the proportion of such workers had dipped to 35.4%. Meanwhile, the unemployment rate went up from 2.5% to 2.7%.

These findings form the crux of a survey on employment and unemployment carried out by the National Sample Survey Organization (NSSO). The survey covered over one lakh households and was carried out between July 2011 and June 2012. The pan-India figures hide a deepening chasm between job opportunities for men and women. While the share of employed men remained roughly constant between 2009 and 2011, women’s employment dropped from 18% to 16%.

Loss of jobs

This may appear a small decline but translated into real numbers the crisis in employment is starkly revealed. In rural areas, about 90 lakh women lost their jobs in the two-year period. This would have been catastrophic but for the fact that in urban areas about 35 lakh women were added to the workforce.

Men joined the workforce in both urban and rural areas, though they got many more opportunities in towns and cities than in villages. Men’s participation in the workforce jumped from 99 million to 108 million in urban areas and from 228 million to 231 million in rural areas.

Unemployment

Kerala had the highest unemployment rate of close to 10% among the larger states. West Bengal (4.5%) and Assam (4.3%) were other large states with relatively high unemployment rates. Among smaller states, Nagaland had a staggering jobless rate of 27%, but this may be compromised data as surveys are difficult in strife-torn areas. Tripura too had a high unemployment rate of over 15%.

Wages

The report also contains striking information on daily wages of casual labourers and regular or salaried employees. In the government’s jobs scheme (MGNREGS), male workers were getting an average of Rs 112.46 per day, while in non-MGNREGS public works the rate was Rs 127.39, and in non-public works it was Rs 149.32. For women, the averages were more similar at about Rs 102 to Rs 110, though lower than men for the same work. This appears to go against a widely held belief that MGNREGS rates are setting the standard for all other wages in rural areas.

The wide gulf in urban and rural wage rates explains why people are migrating to live in cities. A male casual labourer earned about Rs 150 per day in rural areas, but his urban counterpart got Rs 180 per day. Similarly, a salaried employee could earn about Rs 300 per day in rural areas but in urban areas the same would shoot up to nearly Rs 450.

Unemployment among religious groups

2009-10

Urban Sikhs face highest unemployment

Mahendra Singh TNN

The Times of India 2013/07/29

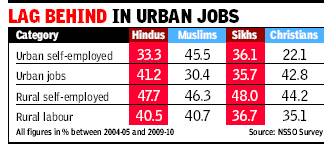

Unemployment was highest among Sikhs living in cities and towns during 2009-10 while the rate of joblessness showed a downward trend for Muslims in both urban and rural areas, a government survey released this month has revealed.

Muslims had the lowest per capita spending, according to the National Sample Survey Organization (NSSO), which in its 2009-10 survey put out a new report on employment trends for religious groups.

Unemployment

Among communities, unemployment increased only among Sikhs living in urban India. The community saw unemployment rise from 4.6% in 2004-05 to 6.1% in 2009-10. However, among rural Sikhs, the rate declined sharply from 3.5% to 2.4% during the period.

The high unemployment rate among Sikhs in urban areas may be attributed to the fact that they are more educated and work with their hands and are vulnerable to economic slowdown which hit India in 2009-10, the period of survey.

In rural areas, unemployment was highest among Christians at 3.9%. However, it declined from 4.4% in 2004-05. The steepest decline in urban areas was witnessed among Christians, with the unemployment rate falling by 5.7 percentage points from 8.6% in 2004-05 to 2.9% in 2009-10.

Hindus had a stable unemployment rate at 1.5% in rural areas during the fiveyear period while all other communities in villages saw a decline. In urban India, the rate fell from 4.4% to 3.4% among Hindus.

Unemployment among Muslims in both rural and urban areas is falling. The rate declined from 2.3% in 2004-05 to1.9% in 2009-10 among Muslims living in villages. In cities and towns, the unemployment rate among Muslims fell from 4.1% to 3.2% during the five-year period. However, most Muslims in both rural and urban areas are self employed.

Spending/ consumption expenditure

Per capita spending was highest for Sikhs, followed by Christians and Hindus.

At the all-India level, the average monthly per capita consumption expenditure (MPCE) of Sikh households was Rs 1659, followed by Christians (Rs 1543), Hindus (Rs 1125) and Muslims (Rs 980).

The survey found that self-employment was the mainstay for all religious groups in rural areas. The major source of earning from self-employment in agriculture was the highest among Sikhs (about 36%), but Muslims topped the chart in the category of rural workers.

In urban India, the proportion of households with major source of earning as self-employment was highest for Muslims (46%). The major source of earning from regular wage/salaries was the highest for Christian households (43%).

Most people irrespective of religious affiliation own between 0.1 and 1 hectare of land. About 43% of Christian households, 38% of Muslim and 37% of Hindu cultivated more than or equal to 0.001 hectare of land but less than 1 hectare. The proportion of households cultivating more than 4 hectares of land was the highest for Sikhs (6%), followed by Hindus (3%).

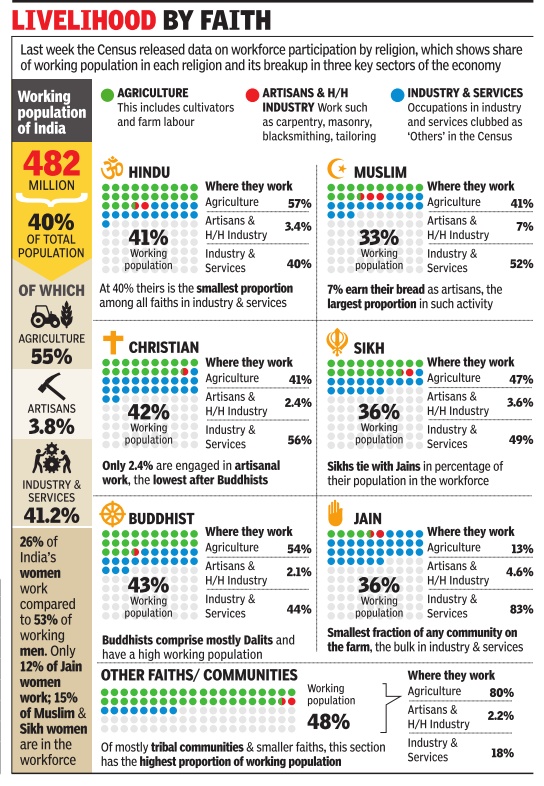

2011: Employment among religious groups

The Times of India Jan 04 2016

Subodh Varma

Buddhists Are Highest At 43%

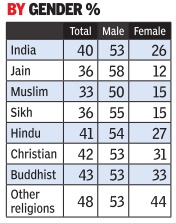

Muslims have the lowest share of working people -about 33% -among all religious communities in India. This is lower than the nationwide average work participation rate of 40%.

The figure for Jains and Sikhs stands at 36% each. Buddhists, comprising mostly Dalits who embraced Buddhism in the 20th century , have a high working population share at 43%. For Hindus, the figure is 41%. Drawn from the Census 2011 data, the statistics show a faith-based profile of India's 482 million strong workforce.The figures haven't changed much from the 2001 Census, indicating a stasis in the economic status of communities.

The key reason behind low work participation rates in some communities seems to be the low work participation of women. Women's participation is just 15% for Muslims and Sikhs, and even lower at 12% among Jains. Among Hindus, there are 27% working women, while it is 31% for Christians and 33% for Buddhists. Several smaller faiths fall under `Other Religions'. These are mostly tribal communities from peninsular India and the northeastern states. Their work participation rates are markedly different from other communities. Nearly 48% of members of this section work, more than any of the country's six major religious communities. Women's work participation is also highest in tribal communities, at nearly 44%.

Census data also provides a picture of how many are engaged in what kind of work. For the country , 55% of workforce is in agriculture, as cultivators or as agricultural workers. The Census classifies all occupations in industry and services as `Other', a convention since British times. This makes up 41% of all workers.Only 13% of Jains are involved in agriculture, the lowest for any community .

While 41% of Muslims and Christians work in agriculture, this goes up to 47% among Sikhs and to 54% for Buddhists. The highest share of workers involved in agriculture is among Hindus, at 57%.

The Jain community is predominantly working in industry and services. Muslims too are largely concen trated in these sectors as are Christians. Muslims are also notably more involved in the `Household Industry' category which is mainly artisanal work like carpentry , black-smithing etc.

Among tribal communities classified under `Other Religions', over 80% of their members are working in agriculture, indicating their poor economic status.

Employment among Muslims

Number of jobless Muslims dips in both villages & cities

But Majority Still Outside Organized Sector

Mahendra Singh TNN

The Times of India 2013/08/19

New Delhi: Unemployment among Muslims is going down, marking an encouraging trend to gladden the champions of inclusive growth.

The unemployment rate for the community declined from 2.3% in 2004-05 to 1.9% in 2009-10 in rural areas and from 4.1% to 3.2% in urban areas. However, a vast majority of Muslims in both rural and urban areas are not part of the organized workforce compared to other religious groups.

In contrast, Hindus had a stable unemployment rate of 1.5% in rural areas during the five-year period while it fell from 4.4% to 3.4% in urban India.

According to data released by the National Sample Survey Organization, Muslims are mainly engaged in self-employment and as rural labour.

In cities and towns, Muslims are at the bottom of the ladder in the ‘regular wage/ salaried’ category. Among the major religious groups, only 30.4% of Muslim households are in regular jobs, followed by Sikhs (35.7%), Hindus (41%) and Christians (43%). In contrast, the proportion of households with major source of earning as self-employment was the highest for Muslims (46%) in urban areas.

In villages, Muslims (41%) are the largest group employed as rural labour with another 46.3% in the self-employed category. Majority of households of all religious groups, other than Muslims, belong to the self-employed in agriculture category, the survey found.

In rural areas, the proportion of households depending on self-employment was the highest among Sikhs (48%). The community’s major source of earning is self-employment in agriculture (around 36%), followed by Hindus (33%) and Christians (30%).

Intake of Muslims in central government organizations has increased by more than 3 percentage points in six years, from 6.93% in 2006-07 to 10.18% in 2010-11. This coincides with directives by the Centre to ministries and departments that they should take special measures to boost minority presence in jobs. That more Muslims are joining paramilitary forces and railways could start a robust trend. Increasing presence in the police would also strengthen their confidence in security matters.

Muslim share in govt jobs moving upwards

Subodh Ghildiyal TNN

The Times of India 2013/08/19

New Delhi: The intake of Muslims in central government bodies has increased by over 3 percentage points in six years, reflecting a visible improvement in the community’s share of public sector jobs that the UPA marked out as priority after coming to power in 2004.

Government figures show that the recruitment of minorities in central government organizations stood at 10.18% in 2010-11, up from 6.93% in 2006-07.

The increase of three percentage points in employment across sectors in the last six years coincides with the directives that the Centre issued to ministries and departments that they should take special measures — publicity campaigns about recruitment drives and inclusion of minority members in interview panels — to boost minority presence in jobs.

Minority has been a thinly-disguised term for Muslims who form an overwhelming share of religious minorities. Social activist and former National Advisory Council member Harsh Mander dubbed the increase as significant and credited the community for the success.

“It is the outcome of efforts on the part of community members to break out of restraints on social mobility they have been traditionally bound by,” he said, adding the government contribution in the trend was smaller.

The percentage of minorities in total hiring across central government jobs was 6.93% in 2006-07. It went up to 8.23%, 9.90%, 7.28% and 10.18% in the following years. Sensing inconsistency, the ministry has called for review of the 2011-12 figures that stand at a dismal 6.24%.

The significance of increasing number of Muslims in central recruitment extends beyond mere job share.

That they are joining paramilitary forces and railways, the largest public sector employers, in greater numbers could start a robust trend for future. The community’s increasing share in the police force would also strengthen their confidence in security matters.

‘Muslims lag in per capita spend’

Around 25% of Muslims are engaged in self-employment in non-agricultural sector, followed by Christians (14.7%), Hindus (14.5%) and Sikhs (12.4%), according to the NSSO data.

The poor state of affairs among Muslims is also reflected in low per capita spending compared to other religious groups. The household monthly per capita consumer expenditure (MPCE), which serves as a proxy for income and is usually taken to reflect the living standard of a family, was lowest among Muslims. Muslim households were spending Rs 980 (Rs 1,272 in urban areas and Rs 833 in rural areas).

The average MPCE (for both urban and rural) was the highest for Sikh households, followed by Christians and Hindus. The average MPCE of a Sikh household was Rs 1,659 (Rs 2,180 in urban areas and Rs 1,498 in rural areas).

Employment in North East India

Job scenario in most NE states alarming

More Workers Join Labour Force Than Jobs Are Created In Mizoram, Meghalaya, Arunachal

Subodh Varma TIMES INSIGHT GROUP

Made up of eight states and accounting for about 4% of India’s population, the northeast is better known for its separatist movements and incendiary ethnic conflicts. It has 25 Lok Sabha members, 14 of them from Assam, and so, does not draw serious attention from political parties involved in the national sweepstakes. The region receives huge funds from the central government that prop up the local economies. But simmering under the surface is a question that haunts everybody — what about jobs?

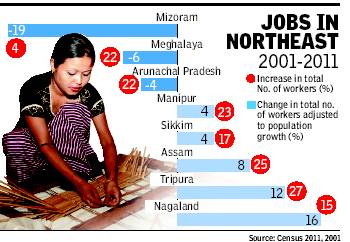

Census 2011 data released this year has some strange and disturbing trends on jobs in the northeast. If states were to be ranked by growth in jobs between 2001 and 2011, Tripura and Assam would figure among the top five states with 27% and 26% increases in total number of workers, respectively. But on the flip side, the growth in workers was just 4% in a decade in Mizoram – the lowest among all states. Three states — Mizoram, Nagaland and Sikkim — were below the national average of 20% growth in workers between the two censuses.

These growth rates may be deceptive because population has been growing in the same period. A better idea of how many jobs are being created can be had by deducting population growth rate from the increase in workers. This reveals a much more serious situation in the northeast.

Three states — Meghalaya, Mizoram and Arunachal Pradesh — show a decline in total workers. This means that more workers are joining the labour force than jobs are being created. Among these, Mizoram is facing a shocking crisis with a decline of over 19%. One factor could be that Mizoram is now an urbanmajority state – over 52% of its population stays in urban areas. So the buffer of agriculture is absent. Seen in the context of the fact that Mizoram has one of the highest literacy rates at 91%, this must be food for thought for policy makers both in Aizawl and New Delhi.

In two other states, Sikkim and Manipur, the adjusted growth rate plummets down to around just 4% in a decade. Tripura with 12% and Assam with over 8% perform creditably in comparison to the other states. Nagaland has the most bizarre situation – since the total population of the state has declined between 2001 and 2011 the two censuses, it shows a rise of nearly 15% in its workforce, adjusted to population.

Lack of growth in non-farm employment in most states, and the difficult hilly terrain, about 70% of which is under forest cover, are two key reasons why employment is stagnating in the northeast, says Bhupen Sarmah, director of the O K Das Institute, a Guwahati-based research institute. “It is an illusion to think that development will take place merely on the basis of injection of funds from the central government. The northeast receives a huge amount of this largesse but look what is the result,” Sarmah points out.

Sarmah may have a point, although it is also true that a lot of the largesse remains on paper. According to the ministry of development of north eastern region, a special non-lapsable fund created for financing projects in the northeast approved projects worth Rs 12,716 crore between 1998 and 2012. Sounds great, but there’s a catch — only about Rs 9,231 crore were actually released and state governments submitted utilization certificates for only Rs 5,641 crore. A Lok Sabha question recently revealed that about Rs 2,000 crore remains unspent from this fund every year between 2008-09 and 2010-11.

Another example is the national job guarantee scheme (MGNREGS) that promises 100 days of employment to anybody who demands. In some states it has become a mainstay of economic support, like in Mizoram with average 73 days of work provided and Tripura (87 days). The national average is just 44 days per household.

But some other states in the northeastern region are drastically lagging — Assam (25 days), Nagaland (35) and Manipur (37).

Eligibility for employment as lecturer

August 11, 2008

SC solves degree puzzle

Degree-holder in Pol Sc eligible to be a lecturer in Public Admn and vice versa

Dhananjay Mahapatra | TNN

FROM THE ARCHIVES OF ‘‘THE TIMES OF INDIA’’: 2008

The Supreme Court has ruled that a degree holder in political science is eligible to become a lecturer in public administration and vice versa.

This important ruling came from a Bench comprising Justices Altamas Kabir and Markandey Katju, which demolished a wedge driven by the apex court in 2001 between the two subjects, treating them as distinct and separate. Dr Rajbir Singh Dalal, who had a masters degree and PhD in political science, was appointed as reader in public administration by the Chaudhary Devi Lal University, Sirsa.

It was challenged in the Punjab and Haryana High Court by a person citing a 2001 judgment of the apex court in Bhanu Prasad Panda vs Sambalpur University, in which it was held that public administration and political science were two separate disciplines. The HC, relying on the SC judgment, cancelled Dalal’s appointment. To arrive at the conclusion, the HC further relied on Regulation 2 of the University Grants Commission (UGC) Rules which state that for appointment to the post of a reader, the candidate must have to be qualified in the relevant subject.

With two sets of disadvantages loaded against him, Dalal moved the apex court. Both Justices Kabir and Katju arrived at the same conclusion, using different routes, to rule that the 2001 judgment was a mere assertion and could not be taken as a precedent. Aided by the support of the UGC which said that the two subjects were inter-linked, Justice Kabir said that in 2001, the apex court did not have the benefit of the UGC’s view and had arrived at the conclusion on the basis of a personal understanding of public administration and political science.

Once the expert bodies had indicated that Dalal, who held a PG degree in political science, was rightly appointed to the post of reader, it was normally not for the courts to question such opinion, unless it had specialised knowledge of the subject.

The 2001 decision of the apex court did not reflect the reason for which the two subjects were not treated to be interlinked, he said and agreed with Justice Katju that expert opinion on such issues should get primacy from the courts.

The employment of women: 2009-12

Rural women lost 9.1m jobs in 2 yrs, urban gained 3.5m

Not Getting Long-Term Work: Survey

Subodh Varma TIMES INSIGHT GROUP

Women’s employment has taken an alarming dip in rural areas in the past two years, a government survey has revealed. In jobs that are done for ‘the major part of the year’, a staggering 9.1 million jobs were lost by rural women. In urban areas, the situation was quite the reverse, with over 3.5 million women added to the workforce.

This emerges from comparing employment data of two consecutive surveys conducted by the National Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO) in 2009-10 and 2011-12. Key results of the later survey were released last month. Both rounds had a large sample size of nearly 4.5 lakh people.

“The survey shows that in the continuing employment crunch in rural areas, the most vulnerable sections — like the women — are getting eliminated,” says Amitabh Kundu, professor of economics at Jawaharlal Nehru University.

If subsidiary work, that is short-term, supplementary work is also counted, women’s employment numbers improve, but they still show a huge decline of 2.7 million in two years. This is a reflection of the fact that women are no longer getting longer-term, or principal, and better paying jobs, and so are forced to take up short-term transient work.

Declining women’s employment in rural areas is a long-term trend in India despite high economic “growth”, says Neetha N of the Centre for Women’s Development Studies.

“Three decades ago, in 1983, about 34% of women in rural areas were working. This has steadily declined and now stands at just short of 25%. But the decline in the past two years is shocking – it is the most drastic decline we have ever seen,” she says.

Low investment in agriculture

‘Poor investment in agriculture behind rural job dip’

Many argue that decline in women’s work is taking place because more women are now either studying or just staying home because the men of the family are earning enough. However,this is not supported by the data, according to Neetha. “Urban areas have more girls’ enrolment in schools and colleges, and better household incomes than rural areas. Yet women’s employment is increasing in urban areas and declining in rural areas,” she points out.

But what is the reason behind this jobs crisis in rural India? “A decline in public investment in agriculture, and in extension work for dissemination of knowledge coupled with increasing mechanization are the main causes of this crisis of jobs,” says V K Ramachandran, professor of economic analysis at the Indian Statistical Institute, Bangalore. He also blames the severe slowdown in expansion of irrigation and supply of electricity to rural areas for causing jobs to dry up.

Satya Narain Singh, deputy director general of NSSO, told TOI that there were no issues of measurement or sample size in the surveys. He pointed out that the population for 2010 was based on Census projections while that for 2012 was based on actual Census 2011 data. This could introduce a small over-estimation of the 2010 population. But the “decline in female workforce is in line with the trend of decline observed in recent decades”, Singh said.

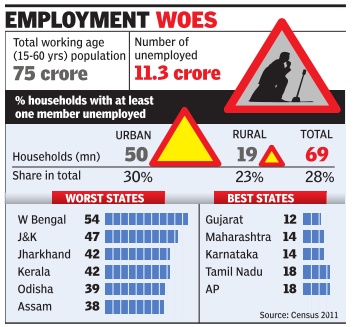

2011: 11.3 crore persons seeking employment

Army of jobseekers now 11cr-strong

Subodh Varma

The Times of India Sep 24 2014

Constitutes 15% Of Working Age People, Spread Over 28% Of India's Families: Census

Over 11.3 crore persons are “seeking or are available for work“, that is, they were unemployed, according to Census 2011 data released on Tuesday .

This huge number made up around 15% of the working age population of about 74.8 crore in the 15 to 60 years age group.These unemployed persons were distributed over nearly 7 crore families or households.That's about 28% of all households in the country .

By categorizing persons as “seeking or available for work“ the Census has differentiated them from those who are not in the job market, which includes housewives and students among others.

This appears to be an alltime high for Census years. In 2001, about 23% of households had members that were unem ployed. Within a decade, this had risen to 28%. In the past three years, no particular spurt in employment growth or poli cies that would catalyse job creation have emerged and the situation continues to be dire.

These exceptionally high unemployment levels are likely to have contributed to the severe loss UPA suffered in the 2014 polls. Many pre-election opinion polls had underlined that unemployment was a key issue with voters. These stark figures would also be a wakeup call for the new Modi sarkar.

As reported previously by TOI, over 20% of youth between 15 to 24 years of age were jobless and seeking work according to Census 2011 data released earlier. In absolute terms, this army of unemployed youth is about 47 million.

The number of unemployed persons is actually more than 113 million because the Census office has released data in terms of how many persons per household are seeking or available for work, and the highest number in that is “more than 4“. For the purpose of the present computation, this has been taken as four persons only . There has been a distinct shift in the employment pattern since 2001. In most states, and nationally , the situation is relatively better in urban areas than rural. Nationally , 23% of urban households reported that they had at least one member unemployed while in rural areas this share went up to 30%. In 2001, the difference was not so much. The reason behind this appears to be the deep agricultural crisis.

Statewise unemployment figures reveal that while most states have approximately the same proportion of households with some member unemployed as the national average, some states have much higher rates. These include Jammu & Kashmir with about 48% households having unemployed persons, Bihar (35%), Assam (38%), West Bengal (54%), Jharkhand (42%), Odisha (39%) and Kerala (42%).

2011-12: small towns as hubs

The Times of India May 24 2015

Subodh Varma

Small towns beat metros as job hubs

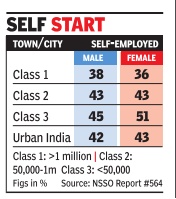

Smaller towns are surging ahead as hubs of jobs and entrepreneurial activity, beating larger cities and even metropolises. While industrial activity declines in big cities, smaller cities and towns are picking up the slack, often displaying a preference for manufacturing at the cost of the services sector. Construction is booming and related jobs are more to be found in smaller towns.These are some of the facets of urban India revealed in a recent NSSO report on employment in cities. Among Class III towns those with a population less than 50,000 nearly 45% of male workers and over 50% of female workers were self-employed. In big cities with a million-plus population, the proportion of self-employed was about 36-38% for both men and women. Self-employed includes very small industrial or service sector units as well as shops.

Salaried jobs up

Compared to 2004-05, in 2011-12, the latest year for which this data is available through NSSO survey reports, there has been a general decline in self-employment while regular wage or salaried employment has gone up in all sizes of cities and towns.

In big million-plus cities, a high 55% of men and 58% of women in the workforce were getting a regular wage or salary . This percentage was below 50 a decade ago. Life is more uncertain and livelihood a work in progress, as one descends the ladder of towncity size. Because, one step down, in Class II cities with population less than one million but more than 50,000, the proportion of salaried workers is 41-43% for both men and women. In towns with less than 50,000 population, the proportion of salaried sinks to just 34% for men and 27% for women.

More jobs for women in small towns

But smaller towns and cities are perhaps going through an evolution that big cities saw a couple of decades earlier. Between 2004-05 and 2011-12, male employment in the tertiary or services sector expanded in million-plus cities from 61 to 63% while industrial employment de clined from about 38 to 36%. But in Class III towns, service sector jobs declined from 53 to 51% while industrial jobs increased from 32 to 35%.For women, the changes were more drastic with industrial jobs declining from nearly 34% in big cities to 29 % but zooming up from 29 to 38 % in small towns.

The smaller the town, the more it is tied up with the rural economy , which provides jobs to an increasing proportion even from urban areas. In towns below 50,000 population, a quarter of the female workforce and about 14% of male workers still worked in agricultural operations, which are physically close and tightly intertwined with the small-town economy . In million-plus cities, just 2% of the female workforce and less than 1% of male workers were involved in agriculture, mostly at the geographical fringes of the metropolises.

The decline of female employment opportunities in these years has led to an increase in urban women working in agricultural activities with their proportion rising from about 18% to 25% in Class III towns. Male participation in agriculture in urban areas has remained stagnant or declined.

Casual labour by men appears to have increased in smaller towns although it has declined for women. In small towns, share of men doing casual work was 19% in 200405 which inched up to 21% in 201112 although the corresponding share of women in casual work dipped from 23 to 22%.

Double income households

Census busts urban myth, finds Bharat has more DINKs

Subodh Varma

The Times of India Aug 31 2014

Rural Figure Is 42% Compared To 22% In Cities

With all the buzz around double-in come power couples, it is easy to believe that more and more urban families have given up the sole breadwinner model of the past. But that would be a mistake, as just released Census 2011 data shows.

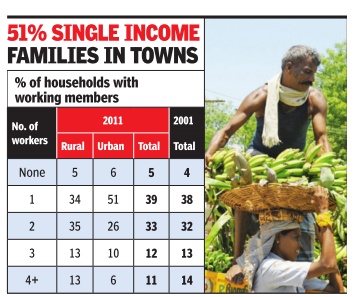

An overwhelming 51% of urban households live on the income of a single earner, while double-income families are a distant 26%. In rural areas, the situation is quite different. While 34% of families have a single worker, double-worker families are slightly more at 35%.

In fact, the double-income-no-kids (DINK) lifestyle celebrated as a cosmopolitan aspiration is prevalent in nearly 42% of two-member rural families compared to just 22% of similar urban families.

If you combine the rural and urban figures, here is what emerges for the India picture: 39% of households sustain themselves on the income of a single working member while 33% depend on two workers. This is not too different from a decade ago, when Census 2001 had revealed that 38% of households had a single breadwinner while 32% had two working members.

Perhaps this is because rural families are bigger and so more members are able to work? Not true. In urban ar eas, nearly three quarters of families have 3-6 members. In rural areas, 66% are in this range. Clearly , this size is the most predominant one in both rural and urban areas. About 17% of families in rural areas have 7-10 members compared to nearly 13% in urban areas.

Two inter-related factors drive rural families towards multiple persons going out to work. The primary reason is economic necessity . Average rural income is estimated at a meagre Rs 6,307 per month for a typical household by the most recent consumer expenditure survey in 2011-12 done by the National Sample Survey Organization. In inflationadjusted terms, rural incomes have increased by a paltry 2% per year. So families need to supplement their incomes. In urban areas, average household income is Rs 11,394 for a typical sized household, and it has increased by a slightly better 3% annually . Alongside economic necessity, the second factor that tilts the balance for multiple worker families in rural areas is women workers. Census 2011 data had earlier shown that the share of working women in rural areas was 35% compared to just 21% in urban areas. This is despite the drastic drop in women’s employment in the past few years. For a variety of cultural, economic and security reasons, most women in urban families are not gainfully employed outside their homes, causing dependence on a single income.

In rural areas, efforts by families to supplement their incomes do not meet with much success because about a third of multiple workers are getting jobs for only up to six months. In urban areas, the proportion of such marginal workers is much lower at 12% to 20%. Marginal workers usually get irregular work for very low wages.

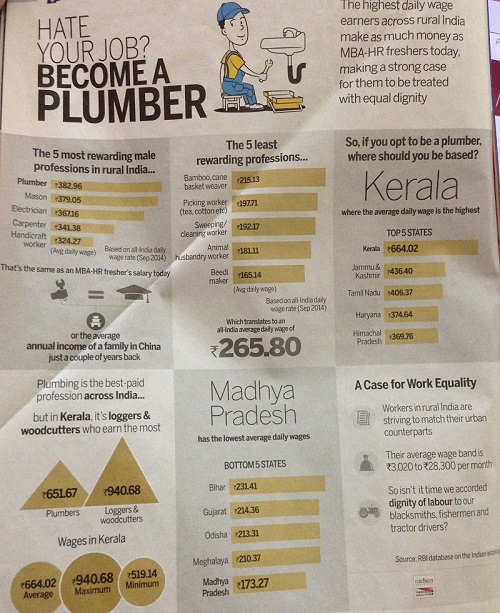

2014: Unemployment among skilled workers

The Times of India, Jul 20 2015

Subodh Varma

Survey: Even among skilled workers, joblessness is high

`14.5% end up without work after training'

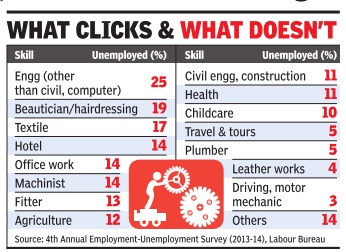

Among those who got formal training in establishments like Industrial Training Institutes or other Skill Centres, the unemployment rate was high -at 14.5% -compared with 2.6% overall, according to a survey done by the Labour Bureau in 2014 and released in 2015.

In a revealing breakdown of skills and the corresponding rate of unemployment, the survey found that except for a handful of trades like leather work, plumbing, motor driving and tourtravel operations, all other categories of skilled persons exhibited double-digit unemployment figures. Some of these are shocking: over a quarter of those who had done engineering diplomas in disciplines other than civil and computers were unemployed. Nearly 17% of those with textile-related training and over 14% with machine operator skills were without jobs.

Unless new jobs, especially in the manufacturing sector, are created, imparting skills to millions will not solve the problem, says IIT-Delhi's Jayan Jose Thomas, who has researched the Indian employment scenario extensively. Existing industry does face a skills gap. That's what entrepreneurs and industrialists keep telling me. So, imparting skills will help somewhat. But the primary thing is to have a policy for industrial growth that will create millions of new, decent job opportunities,“ he told TOI.

About 12 million people join the workforce every year in India. But an analysis of job growth over the past nearly two decades by Thomas, using NSSO and census data, shows that on an average, only 5.5 million new jobs have been added every year in this period.

Labour Bureau data shows that unemployment rates are higher among those with higher educational qualifications. While the overall unemployment rate was reported at 2.6% among the over-15 age population, for postgraduates, it was 8.9%, for graduates 8.7% and for diploma or certificate holders, 7.4%. Experts believe that this could be because qualified persons seek better wages and hence may remain unemployed for a longer period while seeking the best options.

Industrial employers often prefer to employ workers with no formal training but adequate experience over say ITI products, again because of wage issues. According to University of California, Santa Barbara's Aashish Mehta, who has studied the skill gap issue, the decision is more a commercial one than a skill level issue.

The average daily wage of an urban diploma holding worker was about Rs 524 for men and Rs 391 for women according to an NSSO report.Men who have studied up to senior secondary make 45% more and women 28% more.But compared to graduates, the diploma holder will get 56% less if male and around 54% less if female. This gives an indication of how employers will make choices, and may also hint at families making educational trajectory choices. The unemployment rates are higher among those with higher educational qualifications. Experts believe that this could be because qualified persons seek better wages and hence may remain unemployed for a longer period while seeking the best options

2014-15

Unemployment

The Times of India, Jun 25 2015

Ambika Pandit

8.5 LAKH IN 2013 - Number of unemployed rising

Unemployment is clearly a problem in the city but what is more worrying is that between 1995 and 2013, the number of unemployed holding diplomas of various courses has more than doubled from 21,705 to 44,934. This data--part of Delhi Government's Economic Survey 2014-15--raises a serious question about the quality and future of diploma courses and vocational training programmes floated from time to time. In 2013, Delhi had 8.5 lakh unemployed people, significantly lower than the 11.3 lakh recorded in 1997. However the data reflects a very worrisome trend from 2010 onwards as, after falling to 4.1 lakh in 2009 the number has risen steadily . It was 4.9 lakh in 2010, became 6.4 lakh in 2011 and then rose to 7.7 lakh in 2012.

Not only is the rise worrisome but also the educational status of those reeling under the effect of unemployment is a cause of concern and will be a major challenge for the Kejriwal government that won support from youth on the promise of “degree, income aur wi-fi“. The AAP government has talked about vocational training and skill development as part of its long-term education plan.

The Economic Survey makes it clear that many di ploma holders are not getting jobs easily . In 2009, the num ber of unemployed in this category had gone down to 8,766 but rose to 23,361 in 2010 reached 37,554 in 2011 and 44,934 in 2013. The authorities need to fo cus on the vocational courses and diplomas offered in the city. These need to be clearly aligned with the needs of the market. The data also shows that most of the unemployed have studied up to graduation or less. The number of unem ployed in this category in 2013 was 4.9 lakh, down from 5.2 lakh in 1995. However, the large number of jobless youths who have studied up to Class XII shows the lack of courses linked to livelihood.

The number of unemployed graduates and post-graduates in 2013 was 1.9 lakh.Those below matriculation and seeking jobs added up to 1.3 lakh.

2016

The Times of India, Mar 27, 2016

Subodh Varma

In the 2016 Budget session of Parliament, there was an eerie silence on one of the biggest problems facing the people — jobs. Both the Rail Budget and the Union Budget speeches mentioned jobs a handful of times but mostly in reference to future prospects. The debates, including the PM's interventions, followed the trend with hardly any worry about jobs. Meanwhile, in the real world, the job situation is not a happy one. Although current employment statistics are not generated in India, applications in the job guarantee scheme have touched an all-time high and a quick survey of eight industries done every quarter by government indicate a dire situation. Macroeconomic parameters too are not showing any hope. The number of people who apply for work in the job guarantee scheme is a good measure of the employment situation in rural areas.

Till the third week of March 2016, a staggering 8.4 crore persons had demanded work under MGNREGS. That's a 15% increase from the 7.3 crore who demanded work last year. This is a symptom of large scale scarcity of jobs because the wage employment scheme provided only 43 days of work on average in a whole year — instead of the 100 days guaranteed under the scheme —and that too manual labour. Of those who applied, nearly 1.6 crore or 19% were not given work — the highest turn-back ever seen in this scheme. So, the job situation in rural areas doesn't appear to be very healthy.

Another partial measure of recent employment trends is provided by a quarterly survey of eight industries by the Labour Bureau. The last such survey result was released in March 2016 covering June to October of 2015. After the NDA government took over, just 4.3 lakh jobs have been added between July 2014 and October 2015 — lower than the immediately preceding 15 months and the same as the corresponding period of 2012-13 under UPA. Of these, the bulk of jobs have been in IT-enabled services (ITES) and the BPO sector. Besides these two indicators, some of the big economic indicators too are not presenting a very optimistic picture. The index of industrial production measures how industrial production is changing — if it rises, so does employm ent, and if it slows, creation of jobs is affected. Between April 2015 and January 2016, the IIP grew by just 2.7%. In the previous year, the first year of this government, it had grown by 2.6%. For eight core industries like coal, oil, gas and steel, which make up 38% of the IIP, the growth from April 2015 to January 2016 was just 2%.

Agricultural output has meanwhile sunk with gross value added growing at a mere 1.1% in 2015-16, as per latest estimates by the Central Statistical Office. This comes after a decline of 0.2% in 201415. This is the devastation of two successive droughts. Services sector continues to grow with its output rising by 9.2% in 2016. The bottomline is that jobs remain elusive, and measures to create jobs — through infrastructure development or Make in India — are still to show results.