Patents: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

India’s patent regime

‘West should learn from India’s high patent standards

SA Aiyar, The Times of India, 7 April 2013

The [Indian] Supreme Court’s denial of a patent for Glivec, an anti-leukaemia drug made by Novartis of Switzerland, has been widely but wrongly hailed by NGOs and castigated by pharmaceutical companies as an attack on patents and a victory for cheap medicine. Actually, the Court fully upheld the principle of patents, but set a high bar for deciding what’s innovative and what’s mere tweaking.

Till 1995, India refused to patent drug molecules. But as a consequence of WTO membership, India in 2005 allowed product patents for drugs, but only for innovations after 1995. This meant no patent for Glivec, which was patented first in 1993. To get around this, in 2006 Novartis tried to patent a new variation of Glivec, for which it claimed improved efficacy. Some other countries granted patents for this variation. But the Indian Patents Office rejected the claim as insufficiently innovative. So too has the Supreme Court.

Many NGOs hailed the judgment for the wrong reason. The Cancer Patients Aid Association, which led the fight against Glivec, declared: “We are happy that the apex court has recognised the right of patients to access affordable medicines over profits for big pharmaceutical companies through patents.”

False: no such right was recognized by the court. It simply said Novartis had not proved that the new variation was innovative enough. The court clarified that it would grant patents for variations that were more efficacious, but set a higher standard for proof than many western courts do.

NGOs are wrong to paint Novartis as a bloodsucker that pauperizes patients. Glivec has saved lakhs of leukaemia patients from death. This is a great boon, and we must encourage more such life-saving boons by granting patents for new drugs. However, this does not mean giving patents for mere tweaking and “evergreening” of existing drugs through minor variations.

Patents are supposed to spur innovation, but when granted over-liberally they create so much lawsuit risk and cost that they end up hampering innovation, not aiding it. The Economist (UK), no basher of multinationals, acknowledges that over-liberal proliferation of patents fuels many of the American patent system’s broader problems, such as patent trolls (speculative lawsuits by patentholders who have no intention of actually making anything); defensive patenting (acquiring patents mainly to pre-empt the risk of litigation, which raises business costs); and “innovation gridlock” (the difficulty of combining multiple technologies to create a single new product because too many small patents are spread among too many players).”

Patent trolls buy up patents in bulk, typically from bankrupt companies, not for actual use but simply to hit other innovators with lawsuits for patent infringement, forcing them to settle to avoid fat legal bills. One US study estimated such legal costs at $ 29 billion in 2011 alone.

Last year, Google bought Motorola’s failing smartphone business for $ 12.5 billion, to access its 17,000 patents. Microsoft and others paid $ 4.5 billion for 6,000 patents from Nortel. Most of these will never be used in actual production: they are simply kept as legal weapons for possible lawsuits. This has nothing to do with innovation, which patents are supposed to promote.

The West’s over-liberal patent system is broken. It should learn from India’s much tougher system. Patents should be seen as monopolies, to be given sparingly only for genuine innovations where the public benefit clearly exceeds the monopoly cost. This means setting a high bar for innovation. High standards are desirable for patents, as for everything else.

CSIR guidelines: filing of Indian, foreign patents/ 2016

Akshaya Mukul, CSIR wants labs to stop random filing of patents, Oct 19 2016 : The Times of India

The Council of Scientific & Industrial Research (CSIR) has sent out a stern message to its 38 laboratories to avoid indiscriminate filing of Indian and foreign patents.

In order to “inculcate responsible behaviour“ CSIR has decided that “henceforth 25% of expenses incurred on prosecution and maintenance of Indian patents and up to 50% of expenses on foreign patents will be borne by the laboratories“. CSIR director-general Girish Sahni has told laboratories “if they succeed in licensing, headquarter will give you a matching grant“.

In a strongly worded letter to lab heads, Sahni said “patents are just filed for the sake of filing without any techno-commerical and legal evaluation“. He told them that even choice of countries where patents are being filed is “ad-hoc without any logic“. For instance, he said, majority of patents are “bio-data“ patents.

“Individual scientists are using them for getting promotions and labs are pla ying number game. Once the patent is granted, neither the scientist nor the lab bothers about it. There is no serious attempt to find licensee and a review system to periodically look at the portfolio does not exist,“ he said.

In this regard, Sahni pointed out, “Renewal is simply done at the recommendation of the scientist, as a result some patents are maintained till scientist retires. After that labs have no documentation available to even demonstrate the know-how.“

He added that patents are being abandoned after filing and are being allowed to lapse in early years. This, he said, shows that “no due diligence was done before filing but in the process we are spending filing fees and paying attorney fees running into crores of rupees“.

To add to it, he said, there is a cost of manpower in the laboratories for applying to International Patent Union.

“All these expenses goes down the drain. Please note that each Indian patents costs us Rs 2 lakh and cost of US patent is $20,000-plus,“ he said.

Sahni gave the instance of 2015-16 when nearly 400 foreign patents were filed. “If each patent is taken to logical conclusion, our total expenditure will work out to be Rs 56 crore. A poor nation cannot afford to spend this kind of money every year to sustain our ego of being intellectual capital of India,“ the director-general said.

He has told each lab director to take “personal responsibility for IPR and business development, and must put in place systems and processes so that worthless patents are not filed and demonetisation is pursued vigorously“.

Trade Mark Rules

‘Well-known trademarks’

Lubna Kably, India Inc can now register trademark as `well-known', March 8, 2017: The Times of India

Only Courts Had Power To Take Decision Earlier In Disputes

In a significant development, the Trade Mark Rules 2017 -which were notified on March 6 -permit companies to apply for their trademark to be recognised as a `wellknown' one. In simple terms, a well-known trademark is one that is well recognised and any infringement could result in misleading the public.

Prior to this notification, any trademark was held as `well-known' by courts only consequent to a dispute regarding its use, such as when another party applied for registration of the same or similar trademark. IPR advocates have many examples to share.Amul' for instance, was given ` the status of a `well-known' mark, owing to infringement of the mark in the name of `IMUL' by another milk cooperative. Watch manufacturer `Rolex' got a favourable order from the Delhi high court, which recognised `Rolex' as a well-known mark, and restrained Alex Jewellery from using this name for artificial jewellery as it could be misleading the public. Other wellknown decisions are in the case of Whirlpool, DaimlerBenz, to name a few.

“While many Indian com panies who have already registered their trademarks will continue to get protection against registration of conflicting trademarks, the rules will be a boon to foreign companies that do not have a registered trademark in India but at the same time wish to protect themselves. At times, entry of some companies may be restricted -say, an adult ma gazine. Yet, through the process of registration of wellknown trademarks, it will now be easier for the publication to protect its globally recognised trade name. This should also reduce the cost of opposition as, typically , the registrar will cite the registered well-known trademarks as conflicting marks to subsequent applications,“ explains Gowree Gokhale, partner and head of IPR practice at Nishith Desai Associates.

Raja Selvam, managing attorney at Chennai-based law firm Selvam and Selvam, says, “Recognition of a trademark as a well-known trademark will greatly help the trademark owner in opposition or infringement proceedings (eg: Amul vs Imul).The registration fee of Rs 1 lakh is insignificant if compared to the savings in potential litigation costs.“

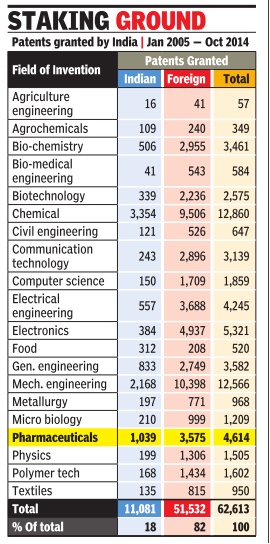

Patents granted by India

In 2005- 14

Jan 27 2015, Sushmi Dey

Promote Indian drugs, US health groups urge Obama

Leading US health groups including AVAC, Oxfam America, amfAR, Health Global Access Project (GAP), TAG (Treatment Action Group)and others have written to Barack Obama urging him to support India in providing “high-quality, low-cost generic medicines essential for health care around the world“. This comes in the wake of the two nations agreeing to enhance engagement on IPR at the latest bilateral talks. The joint statement after the Obama Modi meeting said the two countries expressed interest in sharing information and best practices on IPR, and reaffirmed commitment to stakeholders' consultations on related policy matters.

There are concerns that US is pressuring India to push for liberal policies in favour of pharma MNCs seeking patent protection for their products in India.

“Instead of using your trip to promote the narrow interests of one segment of the pharmaceutical industry, we ask you to support the interests of people who need affordable medicines, whether they live in the US, in India, in Africa or elsewhere,“ civil society organizations said in the letter.

In April, the US brought out the Special 301 report taking unilateral measure to pressure countries to accept IPR protection beyond WTO obligations. The report classified India as a `priority watch list country' , highlighting concerns related to Indian patent law, grant of compulsory licence and inclusion of a statement relating to CL for green technologies in India's manufacturing policy .

Adding Indian laws are compliant to the WTO TRIPS agreement, the civil society letter said, “Recent US policy stances have sought to topple parts of India's intellectual property regime that protect public health to advance interests of multinational pharmaceutical corporations in longer, stronger, and broader exclusive patent and related monopoly rights.“

India is a major manufacturer and exporter of low cost generic medicines. The domestic pharmaceutical industry registered exports worth $14.84 billion in the 2013-14. While the US itself contributes the majority of this sales, India is also a major supplier of generic medicines to other parts of the world.

While India is currently in the process of finalizing an IPR policy and a separate policy for pricing of patented medicines in the country, bilateral talks between the two nations along with Obama's visit to India assume significance not only for the Indian pharma industry but for patients across the world.

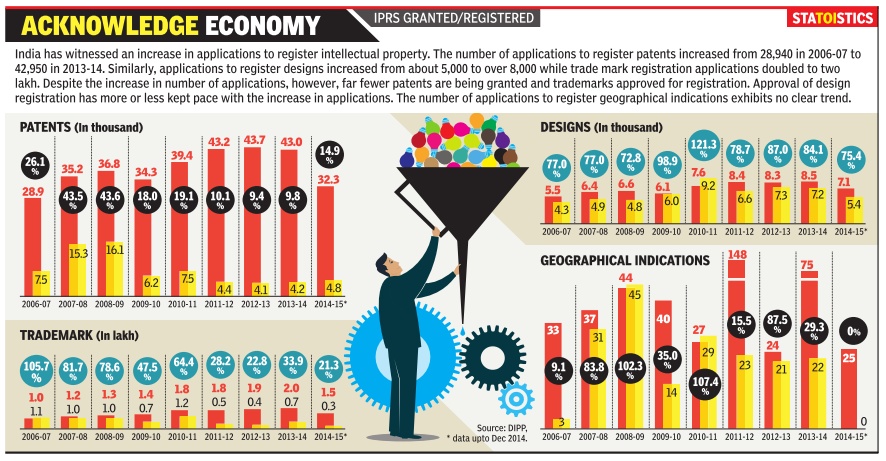

Intellectual property, India: 2006-15

See graphic