Caste, region, religion and Indian cricket

These two cartoons were used to illustrate Mr S Anand’s article hosted on Ambedkar.org etc [2].

Both cartoons are inoffensive—and even sweet.

However, is it necessary to drag caste and politics into cricket—unless the case is that the selection process for the Indian cricket team deliberately overlooks the claims of other castes and, therefore, the team does very badly nternationally.

The racist and pejorative term ‘pappati’ has been used to describe the ‘pot bellied Brahmins’ [3]

He was a great wrestler because he was from Gujranwala, a town known for producing champion wrestlers: Hindu, Muslim and Sikh. Religion and caste were not what made great wrestlers: the great Nurewala school did.

Just as Bombay's cricket nurseries produced Scheduled Caste as well as Brahmin, Muslim as well as Parsi cricketers. Pahelwani

Photo: David Gentle

(Manohar Aich at age 100 in 2012. Like other rural champions--Hindu, Muslim, Sikh, Brahmin, Yadav or other caste—he learnt his ropes at village gyms, in his case the Ruplal Byayam Samiti.

How 'proud and wealthy' his Brahmin family was can be gauged from the fact that he joined the Indian Air Force as a technician--i.e. not as an officer. For the record, he lived in ‘grinding poverty’ [4], which stunted his growth to 4ft 11in. Photo: The Hindu)

This page is an examination of the validity of the |

The sources of this page include

The Times of India<> S. Anand Outlook India In case the Outlook link does not work, Mr Anand's article can be read on Indpaedia itself at Cricket and the Brahmans' bodies.

FP Sports/ First Post Aug 1, 2013<>Salil Tripathi, ESPN Cric Info

The debate

Mr Siriyavan Anand set the ball rolling with his article Eating with Our Fingers, Watching Hindi Cinema and Consuming Cricket (Ambedkar.org). Andrew Stevenson of The Sydney Morning Herald, smarting under the fact that India was often the greatest cricketing team in the world, in all formats, and the team for Australia to beat, caught the ball from Mr Anand and tossed it further.

Mr Stevenson, who cited Mr Anand’s article extensively, described ‘Siriyavan Anand [as] a Dalit (the caste formerly called untouchables) [who] has written provocatively and critically of the Brahmin domination.’

Mr Anand’s hypothesis

Mr Siriyavan Anand’s hypothesis has been reproduced in toto by several websites (including Indpaedia; see Cricket and the Brahmans' bodies) and publications. It is difficult to say where Mr Anand's article was first published, but in all likelihood he gave this honour to the India-baiting Himal, as indicated by his original text [8] Foreigners whose countries have been defeated by India sought solace in Mr Anand's article(s) by citing it extensively. Dalit Nation hailed Mr Anand as ‘The upcoming and budding Dalit Intellectual Siriyavan Anand [who] has analyzed this [caste and cricket] so well. We hope brother S Anand continues to write on engrossing Dalit issues.’ One of the most respected cricket authors, Ramchandra Guha, has cited it even more extensively in a scholarly book.

Therefore, Mr Anand's hypothesis demands to be examined, point by point...

...even though Mr Anand's 'facts' include showing an OBC Muslim as an 'upper caste' (Hindu), showing a Jain as a Brahman, a Ghavri as 'upper caste' and a Rajput hockey player as a Brahman, not to mention talking of meat-eating Jats (and not explaining the present as well as centuries-old Brahmin proficiency in body-building, wrestling and weight-lifting: or perhaps those sports are not 'physical' enough)...his 'hypothesis' still demands to be examined....

Mr Anand writes, ‘I am not a historian of the game [How we wish he were one], but it does not require much disciplinary training [It does] to infer that cricket is a game that best suits brahmanical tastes and bodies.’ [It does. It does. How else do you explain why the Australians, West Indians, Pakistanis and Sri Lankans, too, have done well in cricket? Do they, too, have brahmanical tastes and bodies? And do the Parsis, Muslims, Christians and Sikhs in the Indian team, too? For those who do not follow cricket, these countries have often beaten the Indian ‘Brahmins’—who in turn have beaten them all.)

'As I begin this, I feel weighed down by the burden of addressing (the 'liberal'?) readers on the regressiveness of a film like Lagaan, and even more weighed down by the prospect of convincing them that cricket in India has been a truly casteist game — a game best suited to Hinduism,' writes Mr Anand.

Mr Anand continues:

i) ‘No sport will tolerate such neglect of bodies as cricket in India. [Golf will.] Take Sunil Gavaskar or Gundappa Vishwanath, conservative brahmans both, who could not have afforded their brahman priest-like paunches and dormant slip-fielding if they had been playing a more physical game like hockey.’ + 'Cricket's relative lack of physicality attracted the Brahmins with their fetish for ritual cleanliness.' [9][Anand contradicts himself by writing that Dhyan Chand, India’s {and probably the world's} greatest hockey player ever, was a Brahmin. And is the St Xavier’s educated Gavaskar ‘conservative’ or Westernised? ]

ii) Mr. Anand, according to Mr Stevenson, has written, ‘Why do their fielders not chase the ball to the boundary? Why do Indian batsmen rarely run for singles, apparently preferring to hit the ball to the fence or amble through for two runs in no obvious haste?’ Mr Anand adds: ‘Having too many brahmans means that you play the game a little too softly, and mostly for yourself.’

iii) Mr. Anand examined the ‘Caste profile of one team each from 1970s/ 80s/ 90s’ and rightly concluded ‘So, [there is] an average of 6 brahmans per team.’

(We will take Mr Anand’s word for it. However, we wonder why he chose those particular years. Because in the two sample years that we randomly chose: i)there were only four Brahmins in the 1961/ 62 team; and ii) the 2015 World Cup squad has only three obvious Brahmins and one who could be a Brahmin.

(Secondly, Mr Anand has falsified 'facts' in order to inflate the brahman and 'upper caste' representation even in the teams selected by him.

(Thirdly, the very same teams that are seen by Mr Anand in casteist terms, can be seen by others as being dominated by Mumbai-Maharashtra or Karnataka or a combination of the two.

(Therefore, for Table 1 Indpaedia has taken a much bigger sample of almost all players who represented Indian from 1947 to 2015.)

But what about the other five or six or seven non-Brahmins in the teams sampled by Mr Anand? Did they chase the ball to the boundary? Do they take singles? Or did they, too, have brahmanical tastes and bodies? In which case bodies would have nothing to do with caste. Are paunches unique to Brahmins?

And is Mr Anand’s point that there is disproportionate representation of the upper-castes (which—unfortunately—is a reality for the while) or of the Brahmins in particular? His argument swings between the two positions.

Above all, in his eagerness to show Brahmin/ upper caste domination, Mr Anand has resorted to outright lies.

The upper caste GAHM Parkar

a) He has lumped one Mr ‘GAHM Parkar’ of the 1982 team with the ‘upper’ castes. [10] Well, as he admits, he is no historian. Nor does he know Indian ethnography or even cricket (or how to use Google). Those who do are familiar with Maharashtrian surnames. They know that Pakistan's most famous import from India, Dawood Ibrahim, was born Dawood Ibrahim Kaskar and his sister, the 'Godmother of Nagpada,' was Haseena Parkar.

And GAHM stands for Ghulam Ahmed Hasan Mohammed.

Jain vegetarians b)As for Dilip Doshi, 'being a Jain, he is a strict vegetarian.' (The Smart CEO) Maybe that is why he had a 'soft body' and was suited to cricket.

However, blinded by hatred, prejudice and a vicious desire to prove a falsehood, Mr Anand has lumped Mr Doshi with the 'brahman' (sic) lot.

With meat-eating Pakistan (not to mention meat-eating Afghanistan) doing much worse than India in sports in general (measured in medals per crore of population at Asian and Commonwealth Games), maybe Mr Anand should start asking them to consider turning vegetarian.

And perhaps Mr Anand could consider apologising to the nation for i) letting himself be used by India-baiting foreigners to malign India--based on such outright lies, and ii) sowing disaffection among communities.

Mr Stevenson’s hypothesis

Mr Andrew Stevenson’s hypothesis, too, has drawn widespread attention in India.

Mr Andrew Stevenson’s article ‘A class act?’ (The Sydney Morning Herald) was on firmer ground in the portions where he attributed cricketing success to class rather than to caste, about which he was even more innocent that Mr Anand.

i) Mr Stevenson wrote that ‘Mahendra Dhoni and Yuvraj Singh come from "lower" castes.’

Wow!

The Rajputs are, indeed, one notch below the Brahmins in the ancient books. However, surveys conducted by social scientists (and recorded by Imtiaz Ahmed in his classic ‘Caste and Social Stratification Among the Muslims’), in some parts of the Hindi belt in the late 20th century showed that the general consensus was that the Rajputs were considered the no.1 caste, and Brahmins no.2. For Mr Stevenson’s information, Mr Dhoni comes from the caste of India’s princes, maharajas and rural chieftains. The sources consulted by Indpaedia for Mr Yuvraj Singh list him as a Jatt. The Jats are the traditional kings and chiefs of Haryana (they are the Rajputs of Haryana), while in Western UP and Eastern Rajasthan they share temporal power with the Rajputs. In Indian Punjab the Jatt Sikhs are the most elite caste. In Pakistani Punjab the Jatt is very important, powerful and elite; de facto,they dominate (though on paper the Syeds, Arab-origin Sheikhs, Mughals and even Pathans might rank higher).

ii) Mr Stevenson wrote that Gavaskar was from ‘a proud, wealthy Brahmin family.’ Proud, like conservative, is a matter of opinion. After he wiped out many of Don Bradman’s records (which probably made Mr Stevenson write his factually incorrect and jaundiced article) and held several world records and was the world's no.1 batsman in his time, some pride might possibly have rubbed off on Mr Gavaskar, though this was never obvious from anything that he said or did. But was his family proud or wealthy?

Sunil’s father, Mr Manohar Gavaskar, worked in a textile factory. He said that Sunil ‘never made any demands on [us] because of his powers of observation. "He saw what austere life we had to live once our breadearner, my uncle, passed away prematurely. That meant me surrendering Rs 95 of the Rs 100 salary to my aunt, the balance Rs 5 to my wife for her personal expenses."’ (The Times of India) Rs.100 was probably US $12 a month in those days and Rs.5 around US 50 cents—certainly better off than Mr Kambli’s family, but wealthy? Not even by sub-Saharan standards.

Sunil Gavaskar wrote in Sunny Days (Published by Rupa & Co): “My parents gave me every encouragement and, as an inducement, promised me ten rupees for every hundred I scored. Even in those days the value of money was not lost on me, and I remember one year when I almost put the household budget in disarray with my centuries.” Mid-day

The interview cited above shows Manohar Gavaskar and his wife as simple, God fearing, middle-class people, refusing to take any credit for Sunil’s world records, attributing them entirely to ‘divine help.’

iii) Mr Stevenson wrote that ‘Despite his talents, Kambli was always booed and mocked at his home ground, Wankhede Stadium in Mumbai...Says Kambli. "I think it's because of my caste."’ (Emphasis added)

Always, Mr Stevenson, or only when Kambli was doing badly? If Mr Stevenson cannot prove his always remark he either owes India an abject apology--or risk being branded a mischievous racist trying to split India, the way his forebears did. Or a frustrated loser smarting under India's whipping of his home team--and smashing the records of his nation's sporting icons.

This is what Derek Pringle wrote in The Telegraph, UK in 2007: ‘Kambli reached 200 in front of an ecstatic home crowd in Mumbai.’

David Mutton (CricketWeb) described the scene thus, ‘Surrounding them [Sachin and Kambli was] an adoring home crowd, several of whom sprint[ed] onto the pitch to share his [Kambli’s] joy.’

These two accounts, neither by an Indian, at one stroke, demolish the ‘always’ and expose Mr Stevenson as a liar.

When Kambli (or the Brahmin Gavaskar or the tribal Christian Mary Kom) did well, the nation would cheer, and raucously. When the same stars did badly the crowds would, unfortunately, show a lack of grace. Yes, South Asian spectators do lack grace. But to imply that a crowd of twenty or thirty thousand (Wankhede’s capacity is 33,482) could possibly boo players along caste lines is not only something that has never happened but, logically, can not happen. Firstly, at that stage the crowd is hysterically looking for Indian successes (and caste is nowhere in their minds). Secondly, in a crowd that large the ‘upper’ castes would by definition be in a small minority.

Salil Tripathi, ESPN Cric Info points out that, ‘while the public barracking was disgraceful, Kambli's fall from grace probably had as much to do with his off-field shenanigans, and even more so with his lack of form on wickets with some life.’ Vinod Ganpat Kambli

Sunil Gavaskar was a national hero in 1975—and the only world- beater that India had produced in any sport other than hockey at the time. And he was from a ‘wealthy and proud Brahmin family.' But, as every cricket historian continues to point out ‘Sunil Gavaskar crawled to an unbeaten 36 in 60 overs [during the 1975 World Cup]. [Indian] Fans booed, rattled beer cans, and one [Indian] even rushed to the pitch to admonish him.’ The Indian nation has still not forgiven Gavaskar for that (as countless newspaper articles published in 2015 showed). Gavaskar has apologised (in his autobiography) for that, because he did not have the luxury of saying, "I think it's because of my caste."

In 1982-83 the spectators at Eden Gardens had come to watch Gavaskar score his 30th test hundred and create a new world record. (He had already equalled Don Bradman’s record of 29 Test centuries)

Instead, Gavaskar was caught-behind off the first ball of the Test to Malcolm Marshall.

In the second innings Gavaskar chased a wide one from Michael Holding and was caught-behind for 20. The Indian team was doing very badly as a whole, too. (It was bowled out for 90 the day after.) The Eden Garden crowd threw stones at the Indian team coach. Gavaskar was also accused of selfishness because he attended the launch of his book Idols, on the rest day. (Abhishek Mukherjee, Cricket Country)

His wife Marshneil was also attacked. Gavaskar would write in his book Runs ’n’ Ruins: “What got me hopping mad, and something I will never forgive, is the crowd throwing fruit and rubbish at my wife…Here were people who talk about culture and respecting women, throwing fruits at the wife of a player who has played for thirteen years. And for one bad shot? When everybody else had also failed? Why her? It was not her fault.”

Boorish behaviour did not spare even the man who at the time was India’s (and, soon, the world’s) greatest ever batsman (till Tendulkar overtook him). Gavaskar was livid (as can be seen from the excerpt). But he did not stoop to saying, "I think it's because of my caste" (or ‘It’s because I belong to Maharashtra’ or some other ethnic explanation).

In both cases Gavaskar handsomely admitted that the crowds were angry because he had played badly.

iv) Mr Stevenson correctly writes: The man rated India's best fieldsman, Eknath Solkar, is not a Brahmin. Mr Stevenson has not made the mistake that some other writers have of classifying Solkar as a ‘lower caste.’ For the record, Solkar was of upper-caste origin, but he too came from a lower-class background. (Ref: Sporttaco)

Caste and class have not always been co-terminus. Brahmins, while certainly better off than the scheduled castes, have typically been lower middle class. Therefore, if the fisherman’s wife had brought Gavaskar up, despite his Brahmin (and cricket-playing) genes he was not likely to have been trained by cricket-playing uncles or attended any of the cricketing nurseries of Bombay. His poverty, rather than caste, would have pulled him down.

If Mr Anand cannot make up his mind whether the Brahmins have soft bodies or all 'upper' castes do, Mr Stevenson’s fisherman analogy confuses caste with class.

Mr Stevenson’s real problem is that he is wracked with jealousy because first one Brahmin wiped out many of Australian Sir Don Bradman’s records, and then another Brahmin wiped out what was left. Obviously, both world-beating men were selected to the Indian cricket team because of their caste, not merit.

David Mutton (CricketWeb), who is remarkably balanced because he goes by statistics and not prejudices, observes: Somewhat surprisingly Kambli was selected over Rahul Dravid and Sourav Ganguly for India’s 1996 World Cup squad.

Both Mr Dravid and Mr Ganguly are Brahmins, supposedly pampered, and Mr Kambli from a non-elite caste.

Caste and Indian cricket

The problem is with Indian society—which treated the scheduled castes/ Dalits deplorably—and not cricket, which by the 1960s was as meritocratic as could be.

Salil Tripathi cites the fascinating book, Corner of a Foreign Field: the Indian History of a British Sport by Ramachandra Guha, which recounts the poignant story of the "untouchable" Palwankar brothers - Shivram, Ganpat, Vithal, and Baloo. They were stars of the gymkhanas, and Baloo in particular bowled brilliantly on an all-India tour of England in 1911. And yet, in India, the cups in which they were served tea were made of clay - so much easier to dispose off after they had used them.

Tripathi clearly condemns this.

But obviously cricket was quite meritocratic even in 1911: for not only did the four Palwankar brothers get selected, Vithal rose to become captain.

Casteist locker room behaviour was another thing, though.

Vinod Ganpat Kambli and Doddanarasiah Ganesh, both with short-lived careers, are being talked about as the only post-1947 Dalit cricketers. However, as his Kanadiga friends informed Mr Anand, Ganesh could be a backward caste 'gowda' and Kambli, it appears, is from a fisherman caste and technically not Scheduled Caste.

The theme of Jeeva (2014/ Tamil) is that a brahminical conspiracy is keeping talented non-brahmin cricket players from reaching the Tamil Nadu state team.

At the state level there sometimes are problems: and not always favourable to the Brahmins.

James Astill’s The Great Tamasha, cited by V. Ramnarayan, The Hindu says about Tamil Nadu cricket, “Almost all the state’s first class players were, until recently, Brahmins, mostly recruited from a handful of Brahmin schools. It also claims that “the Brahmin grip is weakening”.

Mr V. Ramnarayan counters: Actually, to charge the Tamil Nadu selectors with playing caste politics is a rather hasty conclusion, not based on fact. The Tamil Nadu cricket team actually had fewer Brahmin players in the early years than in the last forty or so years. The Balu Alaganan-led champion team of 1954-56 for instance was made up almost entirely of non-Brahmins; and the picture actually changed gradually thereafter, to include more and more Brahmins. (To look at some more random samples, the 1999 Tamil Nadu team had seven non-Brahmins in the side, while today, it has five or six on an average). While yes, Brahmins have dominated Tamil Nadu cricket over the decades, caste cannot be said to have significantly influenced team selection.

India has changed so rapidly that for decades it is the Brahmins who have been complaining of being discriminated against. ‘Leftartist’ has a balanced take. He wrote in 2014, ‘It goes both ways.. it all depends on who is the king (of Cricket Board) in that state/City. In Hyderabad where I come from.. I think Brahmins are given last priority (In Cricket) as its ruled by a Yadav (backward caste) and others, until unless you're exceptionally talented like VVS you wont make it.’ Reddit

Above all, Salil Tripathi asks Mr Stevenson: Why it is that 130 years after Australia started playing Test cricket, there has been only one Test cricketer, Jason Gillespie, of aboriginal heritage? In fact, the first Australian team to tour England, in 1868, was made up entirely of aboriginal players Why only cricket: it was the kindness of a few strangers that spotted the potential of Evonne Goolagong who emerged as Wimbledon champion in 1971 and 1980. And there was no Cathy Freeman to hold the Olympic torch at Melbourne in 1956; Australia had to wait till 2000 in Sydney for that, when that delightful athlete, a symbol of Australian reconciliation, not only ran with the Olympic flame, but also won a gold medal.

India, on the other hand, has had two Muslim and several non-Brahmin captains since independence.

The scheduled castes' contribution

Please see Scheduled castes in Indian cricket teams

In order to pad [pun unintended] its case of caste bias, Dalit Nation puts Dilip Doshi, a Jain, and Ashok Malhotra, a Khatri, in ‘the list of Brahmin Indian cricketers.’

Indpaedia, as will become obvious in the next few paragraphs, has NO position in this debate except to investigate into the veracity of every ‘fact’ proffered, every assertion made.

And as for hints of Brahmin-dominated cricket management in India, Lalchand Rajput, who can be considered an SC or ST, was variously the manager of the Indian cricket team and its coach.

Mr Anand has made dark insinuations about 'Brahmin selectors.' Dalit Nation has spelt it out: ‘The Brahmin selectors, the players and Brahmin commentators form a mutual admiration society.’

The fact is that in 2012 the scheduled caste Karsan Ghavri headed a [cricket] Board's initiative to unearth talent through open trials The Hindu. The Indian nation is unique in its secularism. When Syed Saba Karim's eye injury finished his playing career, the system compensated him through his television commentaries and offcialdom by naming him national selector (in 2012).

The castes of selectors could be another Page if Messrs Anand et all so desire.

Incidentally, Wikipedia informs that Babasaheb Dr. ‘Ambedkar was opposed by M.C.Rajah and P.Baloo who joined hands with Congress and Hindu Mahasabha and signed a pact against the position of [Babasaheb Dr.] Ambedkar called 'Rajah-Moonje Pact'... In 1937, Baloo ran against [Babasaheb Dr.] Ambedkar for a designated "Scheduled Caste" seat in the Bombay Legislative Assembly. [Babasaheb Dr.] Ambedkar defeated Baloo.’

Caste, vegetarianism and ‘physical sports’

Let us revert to Mr Anand’s hypothesis, which continues:

iv) ‘Fast bowlers are not what India is known for, except for Kapil Dev, a meat-eating jat.’

It would have been nice if Mr Anand had been a historian before making sweeping and factually incorrect remarks that have been used extensively internationally to malign India.

Remarks like: ‘Whoever has heard of vegetarian kings in late-19th century?’ He obviously hasn’t heard of very much at all.

Remarks like: ‘We are not going to see cricket at the national level being taken over by meat-eating Dalits, Muslims and Sikhs and some much-needed team spirit ushered in.’ [11] or [12]

Kapil Dev might have eaten meat as an individual, but what has his Jat caste to do with that? As a caste Jats are vegetarians who get their animal proteins and 6’ tall, muscular frames from milk and ghee.

The Jat kings were vegetarian even in the 20th century. The same is true of many Rajputs, kings as well as commoners.

‘Ursus of Mysore are definitely vegetarians,’ wrote jeevarathna, adding, ‘To the best of my knowledge all Kshatriya/ Rajputs clans are traditionally vegetarians.’ [13] (Emphasis added. However, if Mr Anand has made generalisations in one direction, this is a generalisation in the other. Certainly not all of them. Rajput ladies in the 19th and 20th centuries were, indeed, mostly vegetarian, but their men less frequently so. Rajput male chieftains from Braj and Madhya Pradesh were overwhelmingly vegetarian in that era.

As for the ‘meat-eating’ Mr Kapil Dev, after admitting to tasting chicken ('I'll taste a butter chicken, but not eat it') and eating seafood, he told UpperCrustIndia, ‘I can eat practically anything - as long as it's vegetarian.’

And if Mr Anand meant that he was referring to Mr Dev’s personal food habits and not those of his caste, why did he not describe India’s first world-beater, Sunil Gavaskar; the world’s best-fielder, Rahul Dravid (210 catches in Tests); and the holder of 19 world-records, Sachin Tendulkar, as ‘meat-eating Brahmins,’ which the three of them are?

(For confirmation of their food habits, see, respectively, (IBN Live), (Rediff), and (Zee News). See (Wikipedia) for the world records.)

As for vegetarians, Krishnamachari Srikanth, who is a vegetarian and a papatti, smashed West Indies’ till-then-invincible meat-eating fast bowlers all over the ground in the 1983 Cricket World Cup final, to emerge as the highest scorer—Indian or West Indian—of that historic match that dethroned the West Indies, forever.

Forget individual eating habits. Are all Brahmin sub-groups vegetarian? As far back as in the 1870s ethnographer Ibbetson had distinguished Punjab regions in which Brahmins were likely to eat animal flesh from those where as a community they were vegetarians. (Kashmiri Pandits have for centuries eaten meat without becoming great sportsmen or warriors. Jats, Yadavs, Gujjars and Brahmins like Yogeshwar Dutt have excelled at power sports without needing to kill animals.)

Above all, can one make a sweeping statement about all SCs (or even Sikhs) being meat eaters? Mr Anand is obviously not aware that some sub-castes within the overall SC umbrella have for centuries been vegetarian ([14]). Though Guru Ravidass (born A.D. 1377) came from the non-vegetarian Chamar community [15], under his spiritual influence most of his followers have traditionally been vegetarian. Their langar (communal kitchen) is always vegetarian.

Obviously Mr Anand neither knows traditional India nor has the desire or a Google connection to find out. If he did he would know that wrestling (a sport that India has won more international medals in than most other sports played by Indians) and body building akharas had and still have a sizeable membership of Hanuman ji-worshipping, gada (club)- wielding, vegetarians, many of who were rural Brahmins, Jats and Yadavs (in addition to meat-eating Muslim and Sikh champions). Rajput champions could be meat-eating or vegetarian.

This has continued into the 21st century, as the Olympic and Commonwealth medals of Sushil Kumar (a Solanki) and Yogeshwar Dutt (a Brahmin), vegetarians both, show. Meat-and beef- eating Pakistanis have introspection to do. Mr Anand has to decide if wrestling is a physical sport or not.

Obviously Mr Anand is not aware of pehelwans like Biddo Brahmin of Nurewala village (born 1872). He rose to the second highest rung in undivided Indian sub-continent despite being a Brahmin and a vegetarian.

‘On the day of the match [c.1905], a confident Gamu [Baliwala, a famous pehelwan] arrived in a grand procession riding an elephant. He taunted Biddo, boasting that he would throw the rice-pudding-eating Brahmin in under two minutes. But in the akhara, Biddo served up his own dish by defeating Gamu in three minutes. Biddo refused to dismount from his opponent’s chest, demanding that Gamu make a public apology for his pre-match outburst. When the referees failed to pull him off, the police were called in to separate the men. Gamu called for a rematch but was convincingly beaten six months later in less than eight minutes.

‘Biddo’s success as a competitive pahelwan won him the title ’Sitara-i-Hind’ (Star of India)’

Biddo defeated respected wrestlers like Jalo Mashki, Partapa, Channan Qasai, Karim Baksh of Sialkot, Khalifa Ghora and Ghulam’s younger brother, Rehmani. However, ‘Biddo was unable to master the upcoming talent of Gama Pahelwan. They met in 1912 during the Shalimar Fair in Minto Park where Gama made quick work of Biddo, winning in less than a minute.’ (From Pahelwani, a site that celebrates Muslim as well as Hindu pehelwans/ champions.)

And, yes, Biddo’s paunch was almost as huge as a Sumo wrestler’s.

Proportional representation in cricket?

According to Mr Anand, ‘Brahmans constitute about 3 per cent of the Indian population’ (Other estimates put the figure higher. The Brahmins claim to be 9 per cent of the Hindi belt.) In the absence of caste-based censuses anyone’s guess is as good as the other person’s. Therefore, let us go with Mr Anand’s 3 per cent figure.

Mr Stevenson’s observation (‘The Brahmin caste, which forms only a tiny fraction of India's population, has always dominated the national cricket side’) is followed by insinuations about caste prejudice being the reason for Brahmin ‘domination.’

The Parsis are roughly 0.00833 per cent of the Indian population.

Going by proportional representation, there should be 1 Parsi player in India’s international cricket teams every 5,454 years. (See 'The calculation of the Parsi share’ elsewhere on this page.)

2.3% of Indians are Christian and 1.9% Sikh. ([16]).

Going by proportional representation, there should be 5 unique Christian players in India’s international cricket teams every 100 years (or one new Christian player every 20 years) and there should be 4 distinct Sikh players in India’s international cricket teams every 100 years (or one new Sikh player every 25 years).

Fortunately, secular India has done considerably better than that for the Parsis, Christians, Sikhs and Jains. The proportion of Brahmins in Indian cricket might be high but the proportion of Hindus is somewhat less than their 79.62% share in the nation's population would entitle them to. (See Table 1.)

And that is the way it always has been in the bureaucracy, the army, indeed every profession requiring education: the Christians, Sikhs and Jains have always been slightly- and the Parsis greatly- ‘over-represented,’ and the Hindus slightly- and the Muslims more-than-slightly- ‘under-represented.’ The per-capita ‘rank’ of the various religious groups in all these professions is roughly the same as their rank on the literacy table. Hindus and Muslims are less literate than the national average, while even the Sikhs are higher. Within the Hindus the Vysya business caste is even more literate and more urban than the Brahmins. And this shows in all competitive examinations.

As for under-representation, in the 20th century not only Uttar Pradesh-Uttrakhand, India's most populous state (and politically the most powerful) but the entire populous-and-politically powerful Hindi belt (including Madhya Pradesh-Chhattisgarh, Rajasthan and Bihar-Jharkhand) have always been grossly under-represented. Because their literacy was much lower than the national average.

Therefore, if the scheduled castes and OBCs have been under-represented it is because of the same reason that kept out even 'forward' caste cricketers of the Hindi-belt. Low literacy.

1961

The wisdom of proportional representation had not dawned on India in the year 1961.

That year there were four Parsis (young Rusi Surti being the fourth) in the Indian cricket team, and normaly three Parsis in any given Playing XI. Thus, 27% of the Playing XI belonged to just one community, which utilised more than its 21,000 years’ quota in a single year.

And yet the 1961/ 62 team that comprised of Umrigar, Engineer and Contractor, a Sikh (AG Kripal Singh), a Muslim (Durani) and a Christian (Borde) did India proud by triumphing over England in the test series. The other players included Gupte (a CKP) and four Brahmins (DN Sardesai, ML Jaisimha, VB Ranjane—a Deshasth Brahmin and VL Manjrekar). [17]

Depending on the sickness that a person’s brain suffers from, a team could look Brahmin-dominated. Or the same 1961 team could look like an almost-entirely Bombay-Maharashtra team (in case the critic suffers from an acute inferiority complex about Bombay-Maharashtra.) AG Kripal Singh, incidentally, was from the state then called Madras.

However, as seemed obvious to most rational Indians, these were the eleven most talented cricket players available in India at the time. And this Amar-Amarjeet-Ardeshir-Akbar-Anthony team of Indians played with ‘much-needed team spirit’ to give India its first series win over England. (Truly sick people can do a caste analysis of which community scored the highest runs and which took the most wickets. The following link will lead to a randomly selected Scorecard [18]) Another scorecard from 1960-61 might show four Parsis in the same test. Had Contractor not had his very unfortunate injury, there would have been many more tests with three Parsis.)

If Kripal had converted to Christianity by then--and it is not clear when he did--make that 'two Christians' but no Sikh in that particular team. (See A.G. Ram Singh family of Madras )

Why do Brahmins do so well?

Why, then, do the Brahmins do so well in cricket?

High literacy

For the same reason as the Parsis once did.

For the same reason that led to Kerala's domination of Indian athletics in the 1980s and 90s—followed first by Karnataka and then, in relation to its tiny population, Manipur. Literacy. Now that literacy in Haryana is high, the state is doing very well with international medals.

Kerala is India's most literate state.

Mizoram is India's no.2 state in literacy--and no.1 in football. Because of its school playgrounds. (See Mizoram: Football and Mizoram: Football stars )

In the 1950s and '60s when Bengal was in the top rungs of India's literacy table, it produced not only India's top three soccer teams and cricketers like P.Roy, it also produced India's first Mr Universe Manohar Aich.

Sports training begins on the school playground. Brahmins and Parsis, like Keralites in general, have literacy. Actually, that is about all that the Brahmins, Keralites, Bengalis and Mizos have, because they have little inherited wealth. And though better off than the scheduled castes, the Brahmins (and Keralites and Mizos) are middle- to lower-middle class. That is the kind of people who have a fire in the belly. Rich business castes do not.

Brahmins from the huge Hindi belt do not see cricket as dominated by fellow- Brahmins. They see a domination by Maharashtra (1960s to the 1980s), followed by Karnataka (1990s).

Ajay Sharma of Delhi would be one such Brahmin. His first-class average was the third-highest of any player to have scored 10,000 runs but he only played one Test. Later when he was implicated in the match-fixing scandal, he received a life ban but Kapil Dev, a Jat, was let off lightly.

If at one stage half the national team was from Bombay it was because of the great cricketing nurseries of Dadar Union and Shiva ji Park Gymkhana, and not nepotism or soft bodies.

Gavaskar’s family was neither rich nor proud, but there was cricket all around him. His family was full of cricketers. His father said, "[Sunil]’s grandparents from mother's and father's side were school chums and played together in the early part of the last century in Shirode near Goa. My elder brother Baban was a left-arm spinner in the class of Bapu Nadkarni and I played club cricket. Sunil's uncle Madhav Mantri played for India. What more do you need." Sunil’s St Xavier's High School was also a factor.

So, while Gavaskar (despite his soft Brahminical body and priest’s paunch) would not have done well had he been brought up by the fisherman who briefly substituted him with his own baby in the maternity ward, if he was able to break the records of Mr Stevenson’s fellow Australian, Bradman, it was because of the cricket all around him, not caste.

Proximity to the game

Mr Anand and Mr Stevenson set the cat among the pigeons, and the intellectuals (caste Hindus, all of them) duly introspected about what they had said, even if both had got their facts seriously wrong.

Ramachandra Guha suggested that cricket was a leisurely non-contact sport, which broadly met Brahmins’ subconscious notions of touch-me-not purity and cleanliness, madi and all. [19]

In The Tao of Cricket, Ashis Nandy came up with heavy intellectual mumbo jumbo, arguing that cricket was inherently suited to the culture of Hinduism: “Particularly recognisable to the Indian elites were cricket’s touch of timelessness, its emphasis on purity, and its attempt to contain aggressive competition through ritualisation.” [20] [Wow! Indpaedia’s non-intellectual volunteers had not even heard posh words like ritualization till Mr Nandy taught them.]

In that case why were the Parsis the first to take to it and the ones who almost monopolised excellence in cricket (and in everything else, from industry to western classical music) till 1906, and thereafter contributed well in excess of their share of India’s population.

Why is cricket equally popular in Muslim Pakistan and Buddhist Sri Lanka, both of which have been world beaters? (If Pakistan did badly thereafter it is because their schooling system, the backbone of all sports, is doing relatively badly compared to Sri Lanka’s, which is the best in South Asia, or compared to India’s, which is the second best. Sri Lanka might not have won many cups after that one triumph but in per capita terms they are still among the best in the world.)

Indian Christians and Sikhs, too, have contributed players in excess of their share of India’s population, though not in as phenomenal an excess as the Parsis, or as noticeable an excess as the Brahmins.

Do the Parsis, Muslim Pakistanis and SL Buddhists (and Indian Christians and Sikhs), too, have subconscious notions of touch-me-not purity and cleanliness, madi and all? Do they, too, admire cricket’s timelessness, its emphasis on purity, and its attempt to contain aggressive competition through ritualization?

The most obvious explanation (after literacy) is that the Brahmins of Bombay- Maharashtra, Karnataka and the west coast, Madras and Calcutta were (like the Parsis before them) ‘exposed to the game far longer thanks to their proximity to the colonial powers, especially in the urban pockets where the colonial administration was headquartered.’ (Arvind Swaminathan Churumuri)

As simple as that.

Delhi was not a Presidency town when Calcutta, Bombay and Madras were. These three towns got their universities in 1857, Punjab/ Lahore in 1882, and Allahabad in 1887. Delhi got its in 1922. Which is why despite the lowest poverty in India and India's highest nutrition levels, the Delhi-undivided Punjab region lagged behind the Presidency towns--and by several decades--in everything: from entry into the ICS to media houses to cricket.

Literacy and proximity were the determining factors.

That is why the scheduled caste Palwankars, who belonged to the Bombay- Maharashtra region, were way ahead of the Brahmins (and Rajputs and Muslims) of the rest of India. Indpaedia is not saying that region, rather than caste, provides the answer (though it is more important than caste). Indpaedia’s case is that ‘proximity to the colonial powers, especially in the urban pockets where the colonial administration was headquartered’ was the single biggest factor.

Then come diet, literacy, family atmosphere (middle class Gavaskar’s cricketing family vs. a Marwari or Gujarati industrialist’s sky-diving and skiing family vs. a Brahmin peon’s family that has no leisure to play anything vs. a polo-playing, shikar-loving Rajput or Muslim zamindar’s family) and the all-important ‘fire in the belly’ that the rich do not have and the poor cannot afford.

Tennis, squash and billiards are upper-middle class games; golf another notch higher. All four have ‘touch-me-not purity and cleanliness, madi and all.’ None of them is a contact sport. All of them tolerate soft bodies and paunches. But as the rungs of the Indian class ladder rise higher, the Brahmin share begins to fall, and precipitously so. For the same reason, their share in these upper-middle and upper-class games declines. (The great Brahmin horse riders were mostly from the families of riding instructors; just as poor squash, tennis and golf players in Pakistan and India have been from the families of caddies, markers and instructors. Like Gavaskar, they had the sport all around them.)

Most of those who have written about the Brahmins’ preponderance in cricket have also mentioned how the majority of India’s prime ministers were Brahmin. Were. Writing at the turn of the millennium, India Today observed how Jitendra Prasada was the only (important) Brahmin leader left in politics. (The Brahmins have staged a mild comeback since then.)

Cricket used to be a middle-middle class game. Now it has reached the small towns and villages of Jharkhand. The scheduled castes have had a substantial share in the middle classes since India’s independence. Therefore, it is only a matter of time before scheduled caste cricketing heroes emerge.

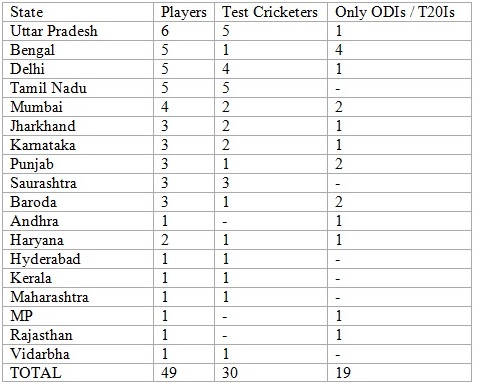

Cricketers' castes:1947-2015

Caste profiles of Indian teams: 1947-2015

Table 1 below has attempted to include all the caste profiles given by Mr Anand in his various articles, and tried to add two teams from each decade after 1950, their names obtained from other sources. Thus, hopefully, every cricketer who represented independent India for five years or more should be on this list.

Information that we have missed may please be sent as a message to the Facebook page Indpaedia.com

Guessing players' castes

Even Mr Anand did not find it easy to do so. Therefore, often he just slotted players as 'upper caste.'

In order to determine the castes of the 121 test cricketers mentioned below, Indpaedia consulted Brahmin Cricketers for the Brahmin players; Rajputanas for the Rajput players; and took Mr Anand’s word for his sample unless he had made a very obvious mistake (eg Parkar) or if he had, rightly, put an umbrella category where he was not sure (eg Amarnath).

Indpaedia assumed that if one Mankad or Joshi was a Brahmin then so must the other Mankads and Joshis be.

For all the rest, we Googled. The beauty of India is that it is not half as obsessed with caste as Mr Stevenson and Mr Anand. Despite extensive Googling there was no mention of the castes of most players: only details of their performance on the pitch.

Which is how it should be.

Similarly, not a single website in a Google search mentions India’s first Mr Universe Manohar Aich’s caste. Indpaedia learnt that he was Brahmin through Answers.com

The states/ regions of the players have, inter alia, been extrapolated from FP Sports/ First Post Aug 1, 2013.

Table 1

|

Name (surname first) |

Ethnicity |

State/ Region |

Team of |

|

Adhikari HR (Colonel Hemchandra Ramachandra) (Hemu) |

Adhikari is a title, not a caste. |

|

1947 |

|

Agarkar Ajit |

Brahmin |

Mumbai |

2002 2007 |

|

Ahmed Ghulam |

Muslim |

|

1951 |

|

Ali S Mushtaq |

Muslim |

|

1951 |

|

Ali Abid |

Muslim |

|

1971 |

|

Amarnath Lala |

Brahmin |

|

1947 1951 |

|

Amarnath Mohinder |

Brahmin |

Punjab |

1978 |

|

Amre Pravin |

Bhandari |

|

1992 |

|

Ashwin Ravichandran |

Brahmin |

|

2015 |

|

Azharuddin M |

Muslim |

|

1983 1992 1996 |

|

Baig Abbas Ali |

Muslim |

|

|

|

Banerjee Subroto |

Brahmin |

|

1992 |

|

Bangar Sanjay |

See note |

|

2002 |

|

Bedi Bishan Singh |

Sikh |

|

1971 1978 1982 |

|

Binny Roger |

Christian |

|

1983 |

|

Binny Stuart |

Christian |

|

2015 |

|

Borde CG (Chandu) |

Christian (Marathi Christian) |

|

1959 1961 1965 |

|

Chandrasekhar BS |

Brahmin |

|

1978 |

|

Chauhan CPS |

Kshatriya Rajput |

|

1978 |

|

Contractor NJ |

Parsi |

|

1959 1961 |

|

Desai RB |

Brahmin (Anavil) |

|

1959 1961 1965 |

|

Dev Kapil (Nikhanj) |

Jat (Kshatriya) |

|

1978 1982 1983 1992 |

|

Dhawan Shikhar |

Khatri |

|

2015 |

|

Dhoni Mahendra Singh |

Kshatriya Rajput |

Jharkhand |

2007 2014 2015 |

|

Divecha RV (Ramesh 'Buck') |

See note |

Gujarat |

1951 |

|

Doshi DR |

Jain |

|

1982 |

|

Dravid Rahul |

Brahmin |

Karnataka |

2002 2007 |

|

Durani Salim |

Muslim |

|

1961 1965 1971 |

|

Engineer FM |

Parsi |

|

1961 1965 |

|

Gaekwad DK |

See note |

|

1959 |

|

Ganesh Doddanarasiah |

Gowda |

Karnataka |

|

|

Ganguly Sourav |

Brahmin |

Bengal |

2002 2007 |

|

Gavaskar SM |

Brahmin |

Mumbai |

1971 1978 1982 1983 |

|

Ghavri Karsan D |

‘Upper caste’ |

Gujarat |

1978 |

|

Gopinath CD (Coimbatarao Doraikannu) |

? (Seems ‘Upper caste’) |

Tamil Nadu |

1951 |

|

Gupte SP |

Chandraseniya Kayastha Prabhu (CKP) |

|

1959 |

|

Gupte BP |

Chandraseniya Kayastha Prabhu (CKP) |

|

1965 |

|

Hazare VS |

Christian |

|

1947 1951 |

|

Irani JK [Jamshed Khudadad (Jenni)] |

Parsi |

|

1947 |

|

Jadeja Ajay |

Kshatriya Rajput |

Gujarat |

1992 1996 |

|

Jadeja Ravindra |

Kshatriya |

Saurashtra |

2015 |

|

Jaffer Wasim |

Muslim |

|

|

|

Jaisimha ML |

Brahmin |

|

1961 1965 1971 |

|

Javagal Srinath |

Brahmin |

|

1992 2002 |

|

Jayantilal HK (Hirji Kenia) |

See note. |

Hyderabad |

1971 |

|

Joshi Sunil B |

Brahmin |

Karnataka |

1996 |

|

Joshi PG |

Brahmin |

|

1959 |

|

Kaif Mohammad |

Muslim |

|

2002 |

|

Kambli Vinod Ganpat |

‘Fisherman’ |

Maharashtra |

1992 |

|

Karthik Dinesh |

Brahmin |

Tamil Nadu |

2007 |

|

Khan Zaheer |

Muslim |

Mumbai |

2002 2007 2014 |

|

Kirmani SMH |

Muslim |

|

1978 1982 |

|

Kishenchand G (Gogumal Kishenchand Harisinghani) |

‘Sindhi’: See note. |

|

1947 |

|

Kohli Virat |

Khatri |

|

2015 |

|

Krishnamurthy Pochiah |

Brahmin |

|

1971 |

|

Kumar Bhuvneshwar (Singh) |

Mavi Gurjar (OBC) |

Uttar Pradesh |

2015 |

|

Kumble Anil |

Brahmin |

Karnataka |

1996 2002 |

|

Kunderan BK (Budhisagar Krishnappa) (Budhi) |

? |

Karnataka |

1965 |

|

Lal S Madan |

Brahmin |

|

1982 |

|

Malhotra O |

Khatri |

|

1982 |

|

Manjrekar VL |

Brahmin |

|

1959 1961 |

|

Manjrekar Sanjay |

Brahmin |

Mumbai |

1992 1996 |

|

Mankad MH |

Brahmin |

|

1947 1951 |

|

Mankad Ashok V |

Brahmin |

|

1971 1992 |

|

Mhambrey PL |

‘Upper caste’ |

|

1996 |

|

Mohammad Gul |

Muslim |

|

1947 |

|

Mongia Dinesh |

‘Upper caste’ (Arora) |

|

2002 |

|

Mongia NR |

‘Upper caste’ (Arora) |

|

1996 |

|

More Kiran |

Kunbi (see note) |

|

1983 1992 |

|

Nadkarni RG (Rameshchandra Gangaram 'Bapu') |

See note |

|

1959 1961 1965 |

|

Nayudu CS |

Balija (See note) |

|

1947 |

|

Nehra Ashish |

Jat |

|

2002 |

|

Pandit Chandrakant |

Brahmin |

Mumbai |

1983 |

|

Parkar Ghulam Ahmed Hasan Mohammed |

Muslim |

Maharashtra |

1982 |

|

Pataudi Mansur Ali Khan |

Muslim |

Haryana |

1965 |

|

Patel Axar |

Patel |

Gujarat |

2015 |

|

Patel Munaf |

Muslim |

Maharashtra/ Mumbai |

2007 |

|

Patel Parthiv |

Patel |

|

2002 |

|

Pathan Irfan |

Muslim |

Baroda |

2007 |

|

Phadkar DG |

Chandraseniya Kayastha Prabhu (CKP) |

|

1951 |

|

Prabhakar Manoj |

Brahmin |

|

1983 |

|

Prasad Bapu Krishnarao Venkatesh |

Brahmin |

Karnataka |

1996 |

|

Prasanna EAS |

Brahmin Madhwa |

|

1961 1971 |

|

Rahane Ajinkya |

Maratha (see note) |

|

2015 |

|

Raina Suresh |

See note |

|

2015 |

|

Raju Venkatapathy |

See note |

|

1992 |

|

Rangnekar Khandu M |

Brahmin |

|

1947 |

|

Rathour V |

Kshatriya Rajput |

|

1996 |

|

Rayudu Ambati |

Kapu Ambati (upper caste) |

|

2015 |

|

Roy P |

See note |

|

1951 1959 |

|

Sardesai DN |

Brahmin |

|

1971 |

|

Sarwate CT |

Brahmin Karhade |

|

1947 |

|

Sehwag Virender |

Jat (Kshatriya) |

Delhi |

2002 2007 |

|

Sen PK |

See note |

|

1951 |

|

Shami Mohammed |

Muslim |

|

2015 |

|

Sharma Chetan |

Brahmin |

|

1983 |

|

Sharma Mohit |

Brahmin |

|

2015 |

|

Sharma Rohit |

Brahmin |

|

2015 |

|

Sharma Yashpal |

Brahmin |

|

1982 |

|

Shastri Ravi J |

Brahmin |

Mumbai |

1982 1983 1992 |

|

Sidhu Navjot Singh |

Sikh |

|

1983 |

|

Singh Hanumant |

Rajput |

|

1965 |

|

Singh Harbhajan |

Sikh |

Punjab |

2002 2007 |

|

Singh Maninder |

Sikh |

|

1983 |

|

Singh Yuvraj |

Jat (Kshatriya) |

Punjab |

2002 2007 |

|

Sivaramakrishnan Laxman |

Brahmin |

|

1983 |

|

Sohoni SW |

Brahmin Deshasth |

|

1947 |

|

Solkar ED |

See note |

|

1971 |

|

Sreesanth Shanthakumaran |

‘Upper caste’ (see note) |

Kerala |

2007 |

|

Srikkanth Krishnamachari |

Brahmin |

|

1983 1992 |

|

Srinath Javagal |

Brahmin |

Karnataka |

1996 |

|

Surendranath, Raman |

? |

|

1959 |

|

Surti RF |

Parsi |

|

1961 |

|

Tendulkar SR |

Brahmin |

|

1992 1996 2002 2007 |

|

Umrigar PR (Polly) |

Parsi |

|

1951 1959 1961 |

|

Uthappa Robin |

Coorgi (Kshatriya?) See note |

Karnataka |

2007 |

|

Vengsarkar DB |

Brahmin |

Mumbai |

1978 1982 1983 |

|

Venkataraghavan S |

Brahmin |

|

1965 1971 1978 |

|

Viswanath GR |

Brahmin |

Karnataka |

1971 1978 1982 |

|

Wadekar AL |

Brahmin |

|

1971 |

|

Yadav Umesh |

Yadav/ OBC |

|

2015 |

Notes on the castes of players

Caste was never as simple as Australian bigots (who think that Jats and Rajputs are lower caste and who are continuing the old colonial tactic of dividing India) and the Anands (who claim that GAHM Parkar was ‘upper-caste,’ rather than Muslim) would have us believe. British censuses—deliberately or inadvertently—had the effect of freezing people in one caste (and one religious group) or another. The centuries old reality—as observed by people who studied caste at the field-level, from Ibbetson in the 1880s to Kumar Suresh Singh in the 1980s—was that there was considerable mobility between castes (and, as Parvez Dewan has observed, between religious groups as well).

That the Hindus are divided into four castes is something you will find ONLY in school text-books, ancient texts written a few thousand years ago (according to British and other Western scholars), if not more than a hundred thousand years back (as Hindu scholars assert), and in some Himalayan regions. Each region of India has its own set of castes (and we are not talking of sub-castes, of which Indpaedia has already recorded around a thousand, with as many more to go).

Bengal has six broad castes, most states at least five. The Coorgis claim to all belong to just one caste. The Sindhis have no 'broad' castes: only a group of sub-castes. In Assam, Manipur and Tripura, too, the caste system is simpler.

As the Indpaedia team looked into sub-castes, it came across several communities—perhaps as many as one in every ten or fifteen—that would start discussions about their sub-caste by saying ‘We cannot be classified under one of the four text-book castes.’ (It is a different thing that others find it slightly easier to put them in one of the four or five or six broad slots.)

While Googling to determine the castes of Indian cricketers, the same happened again.

Kunbi—Kiran More’s community—writers say, ‘It is difficult [to] classify Kunbis as per the Hindu caste system, because for the past many centuries they have been practicing occupations that can be a collective function of Vaishyas, Brahmins, Kshatriyas…’

Here is a classical example of fluidity between castes—in this case between all three ‘upper’ castes.

Divecha’s Prajapati community has a similar take—in reverse. They claim to be former Brahmins who were cursed to become non-Brahmins. Theirs seems a case of the downward mobility of a former Brahmin caste. (The page Prajapati community records its own historians’ contention that Valmiki, ‘a Shudra by birth, was able to become Brahmin.’ With minor variants, all Hindus know about this upward mobility and revere Valmiki ji.) The Prajapati community, too, believes that it is difficult to slot.

And those are two Hindu communities out of an extremely small sample of 15 Hindu communities in Table 1. Thus, one in every seven or eight sub-castes in this sample is difficult to slot into one of the four to six major castes. At the all-India level this may be true of one of every ten or fifteen sub-castes.

The confusion (from Stevenson and Anand’s viewpoint)/ fluidity and flexibility of caste (from the viewpoint of field-researchers ranging from Ibbetson to KS Singh) does not end there:

Bangar, thus, is Maheshwari in Haryana and Rajasthan. However, a Google search also showed some Scheduled Caste Bangars in Haryana (JeevanSathi)

Divecha is variously listed as Shree Gujjar Kshatraya Kadiya Prajapati and Brahma Kshatriya. Google searches indicate that Zanzibar the migrants from India are a potter caste and in India mainly one.

Gaekwad: The ruling princely family of Baroda. The Shinde and Gaekwad dynasties of the Maratha Empire are originally of Kunbi (non-elite tillers) origin. Huge upward mobility. ([21])

Ghavri: Karsan Devjibhai was a Gujarati. Google yields nothing about Gujarati Ghavris but in north India Gavri, Gawri, Ghawri and Ghavri are Aroras, an intermediate caste. Three sites indicate that Karsan belongs to a scheduled caste.

Jayantilal, Hirji Kenia was from Hyderabad. Hirji is a name used by Parsis and Muslims as well. Jayantilal seems to be from a Gujarati family settled in Hyderabad.

Kambli: Even Vinod Kambli’s caste is not clear-cut. As Mr Anand himself points out, Mr Kambli could be from a fisherman caste and technically not a Scheduled Caste.

Kishenchand: Do Sindhis have castes? Yes and no. See Sindhi Hindu 'castes'

Lala Amarnath: Legendary Lala Amarnath (and his son Mohinder) are thought to be Khatris, because of the title Lala. However, a Brahmin list claims them as their own. [22]

Nadkarni is normally, but not always, a Brahmin name. However, the famous cricketer is not on the aforementioned Facebook list. [23] Google searches did not help pinpoint the caste.

Nayudu or Naidu are from the Balija caste. Increasingly they are being seen as Kapu. (Another case of fluidity.)

Patel is a title. While most Patels are Hindu, there are Muslim and Parsi Patels, too. While the Hindu Patels might mostly be ‘proud and wealthy’ landowners, farmers and village leaders, Axar Patel's father, Rajeshbhai Patel, is a retired mill-worker. (DNA)

Wow! Indian cricket is disgustingly elitist. Right, Mr Stevenson?

Bhuvneshwar Kumar’s father, a sub-inspector with the Uttar Pradesh Police (the equivalent of a Warrant Officer in the Air Force), would rank in the super-elite in comparison to Mr R Patel’s. And yet a sub-inspector is two rungs below the lowest ‘gazetted’ (covenanted) police officer: two rungs below a 24-year-old police 2nd lieutenant (called DySP in India). A Google search provoked by Mr Anand and Mr Stevenson revealed that Bhuvneshwar Kumar belonged to the cowherd caste of Gurjars, which has been struggling to get their caste included in the list eligible for affirmative action.

Rahane: Here are contradictory views on the Rahanes: i) ‘Rahanes are Marathas’ (ruling caste) (Shitole); ii) ‘Rahane are not upper castes in Maharashtra at least’ ([24])

Raina: Raina could be a Brahmin, and then maybe not. (Rainas are Pandit in Kashmir but a carpenter caste in the Jammu-Himachal hills. Suresh Raina’s family is now settled in UP. It depends on where it migrated from. The Rainas/ Razdans of 1300 A.D. Kashmir were a ruling warrior caste.) A Google search provoked by Mr Anand and Mr Stevenson revealed online debates on Suresh Raina’s caste: the conclusion was that he could be anything from a Brahmin to a backward-class carpenter-caste.

Raju, Sagi Lakshmi Venkatapathy: Kshatriyas Youth Force lists Venkatapathy in their list of famous Andhra Kshatriyas.

Rajput, Lal Chand: Sport Taco asserts that he is from a scheduled tribe. Banjara Times describes him as the ‘Goaar Cricket Star Lal Chand Rajput.’ Goaar is the umbrella caste of Banjara, Bazigar, Lambani and Lambada. Wikipedia informs us that ‘In some states of India, [the Banjaras] are considered as Scheduled Caste while in other states they are categorized as Scheduled Tribe. In the state Rajasthan, they are Other Backward Classes (OBC) category. In [Lalchand’s] Karnataka, they are categorised as Scheduled Caste since 1977.’ From the same Banjara Times it was seen that they wanted to be categorised as a Scheduled Tribe.

Roy/ Rai/ Ray is a title rather than a caste-name. A Roy could be a Brahmin or a Kayastho.

Sen could be Vaidya/ Baidya or Kayastha/ Kshatriya.

Solkar: i) SportTaco writes: ‘Solkar was of high-caste origin, but he came from a lower-class background. He learnt all his cricket at the Hindu Gymkhana, where his father happened to be the groundsman.’ ii)Wwhen one Shishti Solkar sought to be classified as a scheduled caste, the Delhi High Court pointed out that Solkar’s scheduled caste ‘certificate has been obtained fraudulently and cannot be believed.’ IndianKanoon iii) On the other hand, some people with the surname Solkar are scheduled castes at least among the Telugu people: (SimplyMarry), if not in Maharashtra.

Sreesanth A Google search provoked by Mr Anand and Mr Stevenson also revealed that Shanthakumaran Sreesanth is perhaps the child of an inter-caste marriage. So, which parent's caste should we hold responsible for his deeds--and give credit to for his cricketing prowess?

Increasingly, inter-caste marriages are becoming the norm in urban India.

Uthappa: Do the Coorgis have castes? All that a Google search yielded was that all of them consider themselves Kshatriyas.

Yadav: Umesh Yadav, of course, is a bona fide OBC.

And all these are not new developments. Even the Brahmins who made it to India’s test side were mostly from lower-middle class to middle-middle class families.

It is sickening to drag caste into something as meritocratic as cricket: and if it had not been mostly meritocratic India would not have, off and on (more ‘on’ than ‘off’), from the Gavaskar era (1970 onwards) to 2014 (when India dominated all three formats of cricket), been the team to beat.

However, since Mr Anand and Mr Stevenson have dragged caste in, an investigation into their arguments and ‘data’ became essential.

In 2014 the population of India was a little more than 123 crore (1,23,63,44,631 persons in July 2014) [25].

Let us assume a Parsi population in India of 1 lakh and an Indian population of 120 crore, both figures having been rounded off in favour of the Parsis.

In that case the Parsis are around 0.00833 per cent of the Indian population (1 Parsi Indian for every 12,000 other Indians)

If each cricket player plays for India for only five years (on average) then in a century there are likely to be 220 different players. In that case there will be 0.018 Parsi cricket players in the Indian team every 100 years.

Or 1 Parsi player in 5,454 years.

We have gone over this calculation with simple calculators at least fifteen or twenty times. If we have got our zeroes or other calculations wrong please message us on the Facebook page, Indpaedia.com and we will change the figures.

Secular India: Amar, Amarjeet, Akbar, Ardeshir, Arihant, Anthony

Mr Anand ‘feel[s] weighed down by the prospect of convincing… (the 'liberal'?) readers… that cricket in India has been a truly casteist game — a game best suited to Hinduism.'

Abhishek Mukherjee, the Deputy Editor and highly respected Cricket Historian at CricketCountry.com, has brilliantly lifted this entire ‘weight’ off the muscular shoulders of meat-eating Mr Anand by underscoring the depth of Indian secularism. For Mr Mukherjee’s entire, thoroughly researched, article please go to Cricket Country. Pre-1947 examples have been omitted because the Muslim population of the country, too, was higher then.

Table 1 supports Mr Mukherjee's evidence. Indeed, no sporting country in the world has ever fielded such ethnic diversity in cricket—or any other game—as India has, though the UK might come close some day.

Excerpts from Mr Abhishek Mukherjee's article:

Five religions represented in same Test

The first instance of five religions being represented in a Test [anywhere in the world] happened at Brabourne Stadium in 1961-62 against England. The line-up included Hindus (ML Jaisimha, Vijay Manjrekar, Budhi Kunderan, Ramakant Desai, Vasant Ranjane, and VV Kumar), a Parsee (Nari Contractor), a Sikh (Milkha Singh), a Christian (Chandu Borde), and a Muslim (Salim Durrani). The 11th man in the line-up was Kripal, whose religion at that time was unknown [he was born a Sikh but at some stage converted to Christianity under the influence of a Christian lady], but it would not have affected the record.

Bishan Bedi’s debut — against West Indies at Eden Gardens — witnessed an encore: barring the lone Sikh (Bedi), the side featured six Hindus (Jaisimha, Kunderan, Hanumant Singh, Venkataraman Subramanya, Srinivas Venkataraghavan, and Bhagwat Chandrasekhar), two Muslims (Mansur Ali Khan Pataudi and Abbas Ali Baig), a Parsee (Rusi Surti) and a Christian (Borde). There were a few such occurrences till Borde’s final Test — against Australia at Brabourne Stadium in 1969-70.

Three Sikhs in the same Test

The brothers Milkha and Kripal Singh played together at Brabourne Stadium against England in 1961-62. However, it is not known whether Kripal, born a Sikh, had converted to Christianity before or after the Test.

Balwinder Sandhu made his debut at Hyderabad (Sind) in 1982-83 making it the first confirmed instance of two Sikhs playing for India (the other being Maninder Singh).

Sandhu’s last Test (against West Indies at Ahmedabad in 1983-84) also saw Navjot Sidhu making his Test debut, thus creating the first instance of three Sikhs playing for India in the same Test. It is to be noted that Gursharan Singh, another Sikh, was the 12th man in the Test and became the first ever substitute fielder to take four catches in a Test.

When Harbhajan Singh made his Test debut against Australia at Bangalore in 1997-98, he joined Sidhu and Harvinder Singh (who is a Sikh) to make it the second and last occasion when three Sikhs took field for India.

Two Christians in the same Test

The 2014 Test at The Oval featured Stuart Binny and Varun Aaron — thus making it the first confirmed occasion when India has fielded two Christians in a Test.

(Abhishek Mukherjee adds: Borde and Kripal turn[ed] out for India in the same Test [on many instances. It is not clear if Kripal had converted by then].)

Four Parsees in the same Test

Surti made his Test debut against Pakistan at Brabourne Stadium in 1960-61 to join Contractor and Polly Umrigar. This was the first instance of three Parsees playing in the same Test (the trio have played several Tests together). Surti was dropped later, but Farokh Engineer kept the Parsee balance going.

Contractor, Umrigar, Surti, and Engineer all played at Queen’s Park Oval and Sabina Park during the 1961-62 tour of West Indies before Contractor had the fateful injury. It also turned out to be Umrigar’s last series. Despite their immense contribution to Indian cricket, the Parsees never had more than four representatives in the Indian Test team.

The first Jain?

No Buddhist has played Tests for India, but there has been at least one Jain in the form of Dilip Doshi. Though he played alongside Syed Kirmani and had a small overlap with both Maninder Singh and Roger Binny, at no point of time did representatives from five religions take field during Doshi’s career.

The first all-Hindu team

There is perhaps no bigger evidence of the secularism in India than the fact that the first all-Hindu Test team took field as late as the Edgbaston Test of 1979 [and very few Indian teams have been all-Hindu since then]. With both Kirmani and Bedi dropped, India fielded Venkataraghavan, Sunil Gavaskar, Chetan Chauhan, Dilip Vengsarkar, Gundappa Viswanath, Anshuman Gaekwad, Mohinder Amarnath, Kapil Dev, Karsan Ghavri, Bharath Reddy, and Chandrasekhar.

Two Muslims in the same team

From TOI

The Squad For T20 World Cup In The Windies in 2010 included Yusuf Pathan and Zaheer Khan

The religions of Indian captains

There have been snide insinuations about i) cricket being a Hindu game in India, and ii) ‘much-needed team spirit’ lacking under Brahmins who ‘play for themselves.’ Therefore, it became necessary to examine the religious groups that India’s captains belonged to.

The analysis below reveals that India has done what no other country in the world has done with any sport that has a captain. India has had captains from as many as five different religions: with three (not two as generally imagined) Muslim captains and two Christian and Parsi captains each.

As for the ‘much-needed team spirit,’ when India was a cricketing minnow, it did equally disastrously under Hindu, Muslim and Christian captains. When it started doing well, once again religion was no issue (though Dhoni and Sehwag have the best records). The table below was compiled in Feb 2015.

|

Name |

Years |

Religion |

Win% |

|

Ravi Shastri

|

1987 |

Hindu |

100 (1 test) |

|

Virender Sehwag

|

2005–2012 |

Hindu |

50 |

|

Mahendra Singh Dhoni |

2008-2014 |

Hindu |

45.76 |

|

Sourav Ganguly |

2000–2005 |

Hindu |

42.85 |

|

Rahul Dravid |

2003–2007 |

Hindu |

32 |

|

Mohammad Azharuddin |

1989–1998 |

Muslim |

29.78 |

|

Bishan Singh Bedi |

1975–1978 |

Sikh |

27.27 |

|

Polly Umrigar |

1955–1958 |

Parsi |

25 |

|

Ajit Wadekar |

1970–1974 |

Hindu |

25 |

|

Nawab of Pataudi, Jr. |

1961–1974 |

Muslim |

22.5 |

|

Anil Kumble |

2007–2008 |

Hindu |

21.42 |

|

Gulabrai Ramchand |

1959 |

Hindu |

20 |

|

Dilip Vengsarkar |

1987–1989 |

Hindu |

20 |

|

Sunil Gavaskar |

1975–1984 |

Hindu |

19.14 |

|

Nari Contractor |

1960–1961 |

Parsi |

16.66 |

|

Sachin Tendulkar |

1996–1999 |

Hindu |

16 |

|

Lala Amarnath |

1947–1952 |

Hindu |

13.33 |

|

Kapil Dev |

1982–1986 |

Hindu |

11.7 |

|

Vijay Samuel Hazare |

1951–1952 |

Christian |

7.14 |

|

Vinoo Mankad |

1954–1959 |

Hindu |

0 |

|

Ghulam Ahmed |

1955–1958 |

Muslim |

0 |

|

Hemu Adhikari

|

1958 |

Hindu |

0 |

|

Datta Gaekwad |

1959 |

Hindu |

0 |

|

Pankaj Roy

|

1959 |

Hindu |

0 |

|

Chandu Borde

|

1967 |

Christian |

0 |

|

Srinivas Venkataraghavan |

1974–1979 |

Hindu |

0 |

|

Gundappa Viswanath |

1979 |

Hindu |

0 |

|

Krishnamachari Srikkanth

|

1989 |

Hindu |

0 |

|

Virat Kohli

|

2014– |

Hindu |

0 (till Feb 15) |

Caste and cricket: Conclusion

(This is a tentative conclusion, which will be changed if fresh evidence suggests otherwise.)

To his credit, Mr Anand has not alleged Brahminical nepotism. (Caste prejudice has been insinuated, instead, by Mr Stevenson and Mr Astill, playing the old colonial game of dividing India [and Iraq] by instigating Indian against Indian [and Iraqi against Iraqi].) Mr Anand has attributed the Brahmins’ (now reduced) domination of cricket to the Brahmins' soft bodies being suited to this soft game.

If he removes words like 'Brahmin' and 'meat-eating Muslims and Sikhs,' his hypothesis will become absolutely correct.

i) Cricket is, indeed, not as 'physical' a game as hockey or soccer. It is certainly a relatively genteel sport.

ii) The mostly-urban cricket players of India (and Pakistan and Sri Lanka, not to mention Muslim-majority Bangladesh) do, indeed, have softer bodies a) than their British, A-NZ and West Indian counterparts, and b) than their rural counterparts in their own countries.

iii) Mr Anand has not examined the ‘hardness’ of the bodies of other urban castes like the Kayasths, Vysya (business caste), urban Nairs, Khatri Sikhs (he assumes that all Sikhs are into physical sports) and urban Muslims (he assumes that the urban Bohra-Khoja- Memon is as hardy as the rural Jat- or Gujjar- Muslim). If he did, he would find, for instance, urban Khatris (Hindu as well as Sikh) doing well in cricket but being totally absent from hockey and wrestling.

iv) Brahmins, contrary to the image people like Mr Anand would like to create, are NOT entirely a priestly- cum- scholarly class. (Several soldier and cook clans, and some gardener clans, are Brahmin). Contrary to Mr Stevenson’s unfounded remarks, as a caste they have never been wealthy. Brahmins have always been more rural than urban, more middle-middle- or lower-middle- class than affluent. (Rich priests like those of Jagannath Puri form around 1% of the Brahmin population Sepoys like the legendary Mangal Pandey are the majority.) Rural Brahmins have been foot soldiers in traditional armies.

Mr Anand writes: ‘India's most celebrated hockey player, Dhyan Chand, though, was a brahman who joined the First Brahman Regiment at Delhi in 1922 as a 'sepoy'.’ But a) Brahmins, by Mr Anand’s definition, have soft bodies; and b) Mr Anand classifies hockey as a physical sport. If Mr Anand’s Brahmin= soft body thesis is accepted then the contradiction of a Brahmin being the greatest ever hockey player in South Asia, if not the world [400 international goals; three Olympic gold medals for his team] cannot be explained.

(Mr Anand has got countless facts wrong in his article that has been cited around the world. Dhyan Chand's caste is one of them. In all probability Dhyan was a Punjabi Rajput {as the site Rajputanas points out}. However, 'Subedar-Major Bhole Tiwari of Brahmin Regiment became Dhyan’s mentor inside the Army and taught him the basics of the game' [26]. That brings us back to hockey being the game that poor Brahmin sepoys once played, till some of their descendants rose to the middle class and played cricket, and some rose higher up to play and become champions in other games like tennis and badminton.)

In academics it is a crime and an unforgiveable sin to confuse class with caste. Mr Anand's article is a diatribe and a polemic, not deserving to be taken seriously considering how easily verifiable his lies are.

The Brahmins' excellence in sports can be explained only if the softness of body is delinked from caste, religion and even eating meat. (Hindu wrestlers—notably Sushil Kumar—and weightlifters have traditionally been vegetarian.) In terms of medals per crore of population India has done much better than ‘meat-eating’ Pakistan, Afghanistan or Bangladesh. Sporting success, it is repeated, has a strong correlation with literacy. Which is why tall, meat-eating Afghans get no medals; smaller Sri Lankans do.) The hardness of a sportsman’s body should instead be linked to his childhood lifestyle and that of his family (urban/ rural, working in a physically strenuous profession or a desk-/ classroom- bound one) and whether the environment of the player’s region favours sports or not, and which sport.

Regions: If Indian hockey had nuseries in Indian Punjab (and UP), cricket had them in Bombay, soccer in Calcutta, Nagaland and Mizoram, and boxing in Manipur. Mary Kom is a tribal. Some people following Mr Anand’s lead have tried to attribute her success to her Christian religion and her being a tribal—rather than to Manipur’s sporty environment, which covers all religions and castes. Attempts to do so have failed [you can do a Google search] because this environment was largely created by the equally great Ngangom Dingko Singh, who incidentally was a Hindu Meitei. He was neither a Christian nor a tribal. When Bombay did well in cricket, not only the Mankads and Gavasskars but also the Umrigars and Contractors, and Kamblis and Solkars, and scheduled caste Palwankars, did so. When Bengal took to soccer there was little difference between a ‘Mohammedan,’ an East Bengali and West Bengali.

It is the environment, not ethnicity.

Caste-, religion- and region- based arguments are sick—unless backed by statistics of runs, wickets, goals and international medals.

Indpaedia has NO position in this debate. Mr Anand and Mr Stevenson started it. Therefore, Indpaedia had to investigate it. Indpaedia will go whichever way the evidence points.

Readers are requested to help Indpaedia i) by filling the blanks (regarding caste and region) in the table on this page; ii) giving evidence (eg players of such and such castes or regions score more runs/ goals or take more wickets than others) and history (eg when India had four Parsi players—e.g. in 1961—it performed like this and when it fielded six Brahmins the results were like that).

Please send facts (not arguments) as messages to our Facebook page Indpaedia.com

Cricket and the Indian regions

Which region dominated 2003-13?

Caste-wise the Brahmins have, because of their soft bodies and paunches, been the single-biggest ethnic group in the Indian national team, as we have seen. (And not because of merit or because two Mumbai Brahmins between them demolished almost all of Sir Don Bradman's batting records.)

However, when it comes to the regions of India, cricketers from which region have the softest bodies? Mumbai, obviously, because traditionally that one city has sent the biggest contingent to the Indian team. For a while, in the 1990s, players from Karnataka must have developed soft bodies and priestly-paunches because they were the biggest group within the national team.

In the 21st century (between 2003 and 2013) UP players must have had the softest bodies—because they had the largest number of players entering the team. At the end of that period, in 2013: Saurashtra had the biggest representation, followed by Haryana.

1950s, 1980s, 1990s—and 2006: Bombay dominates

There were six Indian test teams between 1952 and 1955-56 that had seven players each from Bombay/ Mumbai.

(Till 2013, Bombay had won 40 Ranji Trophy championships and been in 44 of the 68 finals.)

In the 80s and 90s, as many as ten players from Mumbai played for India. Eight of them made their debut during that period. In addition to those mentioned in Table 1 on this page, these were: Balwinder Singh Sandhu (a Jatt Sikh), Sandeep Patil (a Kunbi), Lalchand Rajput (apparently a Rajput, though he has been claimed by a caste/ tribe website as what might be a scheduled caste), Salil Ankola [Ankola is a place, not caste].

Then, in 2006, Mumbai again had five players in the national team (including Ramesh Powar).

Karnataka’s decade: The 1990s

There were times in the 1990s when the national team had as many as five players from Karnataka alone.

2013: Saurashtra no.1, Haryana no.2

At one stage in 2013 Saurashtra contributed the largest number of players from any region: three – including Cheteshwar Pujara and Jaydev Unadkat. Haryana had the second highest number.