China-India economic relations

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Some indicators

China - India economic relations: some indicators

Bans/ curbs on Chinese products

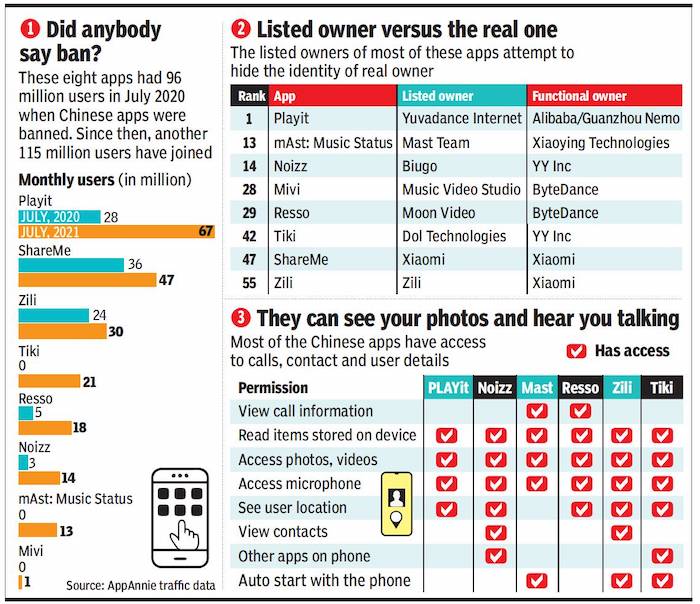

2021: Chinese apps grow despite ban

Pankaj Doval, August 30, 2021: The Times of India

From: Pankaj Doval, August 30, 2021: The Times of India

See graphic:

Chinese apps in India, as in 2021 July

A year after the government swooped across the Chinese app ecosystem in the country for engaging in activities “prejudicial to the sovereignty, integrity and security of India”, many apps from the neighbouring country continue to grow exponentially — some from companies that were explicitly banned, such as Alibaba, Bytedance and Xiaomi. Most of these companies have attempted to hide their Chinese origins, listing their apps with new company names, and with little public information about the ownership of the apps.

A TOI investigation finds that at least 8 of the top 60 apps in India today are Chinese-operated, and together reach over 211 million users every month. The same apps had 96 million users in July 2020 when Chinese apps were banned — implying that they have acquired 115 million new users in the last 13 months.

The government had, in an unprecedented measure, brought down as many as 267 Chinese apps in India last year, using provisions under Section 69A of the IT Act. The clampdown of 2020, at the height of border and diplomatic tensions between India and China, had seen the government take down Tik-Tok, UC Browser, PUBG, Helo, AliExpress, Likee, Shareit, Mi Community, WeChat, CamScanner, Baidu Search, Weibo and Bigo Live, apart from some apps from Xiaomi.

The ban, the government had said, was imposed to ensure safety and security of the citizens, including data protection, and had been recommended by the home ministry.

“The ministry of electronics and IT has issued the order for blocking the access of these apps… based on the comprehensive reports received from Indian Cyber Crime Coordination Centre, ministry of home affairs… Government is committed to protecting the interests of citizens and sovereignty and integrity of India on all fronts and it shall take all possible steps to ensure that,” the government had said.

However, the entry of similar apps in a new avatar seems to have gone unnoticed, especially as the companies have been growing in strength in the country. Most of the companies have attempted to hide their Chinese roots, listing their apps with new company names, and sometimes with little public information about the ownership of the apps.

Nearly all the new apps belong to the media and entertainment space, which is where companies such as TikTok (by Bytedance), and SnackVideo (by Kuaishou) were operating when banned in 2020. Experts believe that Chinese companies have targeted this category because it allows them to quickly reach a large audience base. Indeed, some of the apps launched after the ban have managed to add tens of millions of users in just months.

The fastest-growing Chinese app is also the fastestgrowing app in India: Playit. The app has grown quickly by promoting piracy. Along with playing videos, users are able to download pirated copies of movies and shows via Telegram, including shows from OTT platforms like Netflix, MXPlayer, SonyLiv, and play them back in the Playit app.

When contacted, the public relations teams of Bytedance and UC Browser did not comment. A spokesperson for Xiaomi said, “Being a responsible corporate, we give paramount importance to ensuring that we are compliant with all Indian laws and the orders issued by the Indian government and have always abided by this principle.” The company said that “all the Xiaomi apps owned (functionally or otherwise) that were ordered to be blocked for access in India have been duly blocked and removed from our smartphones and we have also taken all measures to inform users about these blocked apps”.

Government officials TOI spoke to said that any action on the new apps will be taken only after the security agencies raise a red flag over their functioning. Even last year, the ban was ordered by the IT ministry after the security establishments found apps’ activities not in consonance with India’s security interest. Finally, a special multiministry committee dealing with IT Act’s Section 69A had given a go-ahead to the ban.

Should security agencies do a re-check? A quick review of six Chinese apps showed what kind of user data they are collecting. Three apps could read items stored on users’ devices and access videos, photos and microphone. Most could track user location.

Meanwhile, on the Google Play Store, most of the Chinese companies providing these apps are either not listed directly or are listed with company names that are hard to trace to their primary owner. However, when looking at information found on their corporate websites for partnerships, public records on ownership patterns, and LinkedIn for recruitment & hiring, a clearer picture emerges.

In some of the cases, the owner of current Chinese apps is also an owner of apps that were banned by India last year. And in many of these cases, as LinkedIn data shows, employees were shifted from the banned application to the new application. For example, the former head of TikTok was moved to head Resso within Bytedance in July this year. Clearly, prima facie, there is a case to check if the reasons that led to invoking the ban last year have come into play again.

Border trade

Sharp dip in imports/ 2016

Pithoragarh:

The cross-border trade at Taklakot mandi in Purang district of China's Tibet Autonomous Region where traders from Uttarakhand have traditionally been selling their wares has seen a sharp rise in Indian exports (Rs 5.86 crore) this year, while the Chinese goods they bring back after their five-month stay saw a slump as they amounted to just Rs 64 lakh.

This year saw a wide gap between exports and imports.In 2015, the trade volume with China through Lipulekh Pass was Rs 4.36 crore, of which Indian traders exported goods worth Rs 1.6 crore while imports from China were worth Rs 2.76 crore. In 2014, imports from the local Bhutia traders were worth Rs 2.14 crore, while they sold goods worth just Rs 1.9 crore.

Indian exports from the district include carpets, bamboo, matchboxes and packed sweets, while the traders bring back readymade garments, jackets and raw wool.“A total of 195 trade passes were issued this year, of which 77 were for traders and 118 were for helpers, but no Chinese traders came to the Indian mandi in Gunji,“ said P S Kutiyal, assistant trade officer.The final figures for this ye ar's trade can be calculated only after all the traders reach the Gunji mandi and pay their customs duty , he said.

The cross-border business takes place between June and October each year when traders make the journey across the 17,000-foot-high Lipulekh Pass to Purang. The trade time was extended by a month after traders petitioned to the government, saying early closure will lead to financial losses. “The trade for this year closed on October 31 as all the traders and helpers have come back from the Chinese mandi in Taklakot,“ said Kutiyal. The temporary branch of the SBI in Gunji has no facility of currency exchange.

“Absence of this facility makes the exchange rates costlier as traders have to pay Rs 11 for one Yuan, while the current rate is Rs 9.89 for a Yuan,“ said a trader. “We had submitted a memorandum to the central government and local trade officer to set up a currency exchange centre in SBI Gunji, but nothing has been done in this regard,“ said Garvuyal. Also the Chinese authorities do not allow transport animals like mules or horses after the Lipulekh Pass, which makes the products costly , as traders have to hire Chinese vehicles to carry their goods.

China's investment in Indian start-ups

2015, 2016

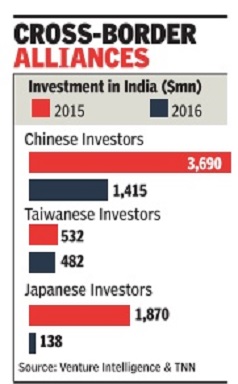

From: Other Asian firms' investment in startups nowhere close to China's, Nov 20 2016 : The Times of India

Other Asian firms' investment in startups nowhere close to China's, Nov 20 2016 : The Times of India

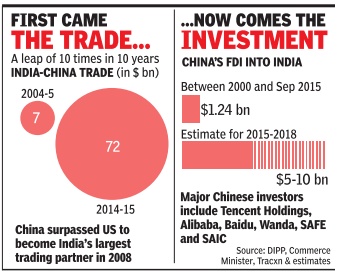

Chinese firms and funds have become big investors in Indian startups, and they are becoming particularly useful now as US funds slow down.Beijing Miteno Communication Technology , a Chinese tech conglomerate, made this year's biggest acquisition in the technology startup space -the $900 million buyout of Media.net, a subsidiary of Mumbai-based Directi, founded by brothers Bhavin and Divyank Turakhia.

Ecommerce giant Alibaba has made large investments in Paytm and Snapdeal. Didi Chuxing, the equivalent of Uber in China, has invested in Ola. Internet giant Tencent recently led a $175 million funding in messaging app Hike; prior to that, it led a $90 million round in healthcare solutions firm Practo and, through its joint venture with South Africa's Naspers, invested in online travel firm Ibibo Group.

“There are demographic similarities and both countries are seeing consumer growth for digital firms. Also, Chinese players have experience in market creation and running successful digital companies, so they can play a bigger role than being just financial investors,“ says Ashish Kashyap, founder of Ibibo, which last month merged with rival MakeMyTrip. Alibaba, for instance, is seen to be actively helping Paytm in various aspects.

Bhavin Turakhia says the Chinese understand the Indian market better than US companies do as the Indian market is on the same evolution path as that of China, but about five to 10 years behind. Chinese companies and funds have become big investors in Indian star tups. Cheetah Mobile, which owns products like Clean Master, invested in fitness app GOQii late last year.

Ctrip, one of China's largest online travel companies, invested $180 million in MakeMyTrip in January . China-based investment firm Hillhouse Capital has invested in Car Dekho. Smartphone maker Xiaomi led a $25-million funding round in content provider Hungama Digital Media Entertainment in April.

Web services company Baidu has said it is scouting for investment opportunities in Indian startups.

Even other Asian companies are nowhere close to investing as much as the Chinese in Indian startups. Japan's SoftBank and Singapore's Temasek are among the few non-Chi nese ones that have made investments. Taiwan's Foxconn has also made several investments, like in Qikpod, Hike and Snapdeal, but some see Foxconn as practically a Chinese company , given that much of its operations is in China.

What's pushing the Chinese tech companies to make large investments are two things: one, many of them are making big profits in their home market, thanks partly to the restrictions on foreign competi tion; and two, the Chinese economy is slowing down.

So they want to use their surpluses to expand into what is potentially the world's third largest digital market.

“There are only two big growing markets where they can invest: India and the United States. Silicon Valley does not respect Chinese capital. So the Indian tech sector becomes attractive to them,“ says Mohan Kumar, executive director at Norwest Ventures, a US-based venture fund that has opera tions in India. Kumar also notes that Chinese investors often value Indian startups at three to five times more than what other seasoned investors do. “So entrepreneurs naturally prefer them,“ he says.

Higher valuations mean the Chinese investors take lower stakes for the same amount of investment, and founders can hope for an even higher valuation in their next round of fund raising.

Language and politics are a challenge. May be for that reason, the Chinese are for now preferring partnerships and not outright buys. Even investment firms are building partnerships. Chinese VC fund Incapital has tied up with Indian fund IvyCap Ventures to enable its partner investors to have a closer look at potential investment opportunities in Indian startups.

China is showing interest in traditional industries too. In July 2016, Chinese pharma compa ny Shanghai Fosun Pharmaceutical Co acquired Indian injectables manufacturer Gland Pharma for $1.27 billion, and in August, Chinese conglomerate Jiangsu Longzhe Technology and Trade Development Co acquired Diamond Power Infrastructure, Vadodara-based manufacturer of cables, conductors, transformers and other power sector equipment, for $125 million. But digital technology looks to be where the biggest action is.

Directors of Indian companies who are Chinese nationals

2021

Dec 12, 2022: The Times of India

NEW DELHI: The government said there were 3,560 companies in India with Chinese directors. In a written reply to the Lok Sabha, corporate affairs junior minister Rao Inderjit Singh said there were 174 Chinese companies registered as foreign companies having place of business in India with the ministry.

“It is not possible to give the number of companies having Chinese investors/ shareholders as the data is not separately maintained in the MCA (ministry of corporate affairs) system,” he said.

The corporate data management (CDM) portal has been developed by the ministry as an in-house data analytics and business intelligence unit.

The government has amended certain rules and forms prescribed under the Companies Act, 2013 to regulate incorporation of companies, the appointment of directors, issuance & transfer of securities and undertaking compromise, arrangements & amalgamation in cases where land border countries entities (LBCEs) are involved.

“New requirements have been provided through such amendments for disclosures, in such cases, about government approval obtained under the Foreign Exchange Management (Non-debt Instruments) Rules, 2019 or for obtaining security clearance from the ministry of home affairs, government of India,” the minister said.

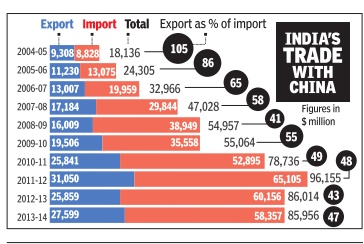

Exports from China to India and India to China

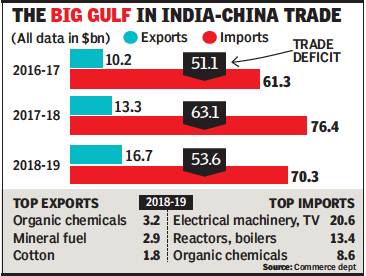

2014-18: trade gap widens from $48bn to $53bn

From: Sidhartha, India to seek easier export rules to China, March 26, 2018: The Times of India

See graphic:

India-China trade, imports and exports- 2014-18

2015: India has a $3,540.5m deficit every month

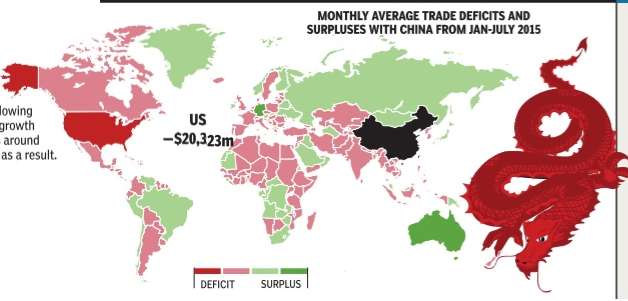

The Times of India, September 27, 2015

China's economy is slowing from its double digit growth and many economies around the world are reeling as a result.Its trade partners, including India, have seen once dependable surpluses wither away, or already existing deficits compound.India counts a $3,540.5m trade deficit on average a month, according to data clocked between January and July 2015

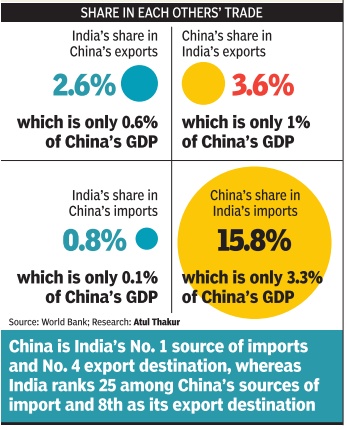

2016: China no.1 source of India's imports, no.4 destination for exports

Calls for boycotting Chinese goods don't sound practical in the present trade scenario. China is the largest source of India's imports while it is the fourth largest destination of our exports. Trade with India is a much smaller fraction of China's total trade volumes

i) The imports of China and India from each other as a percentage of the other country’s GDP

The Times of India

2015-19

From: Oct 13, 2019: The Times of India

See graphic:

China India trade, 2015-19

2019- 23: China India and comparable countries

April 19, 2023: The Times of India

From: April 19, 2023: The Times of India

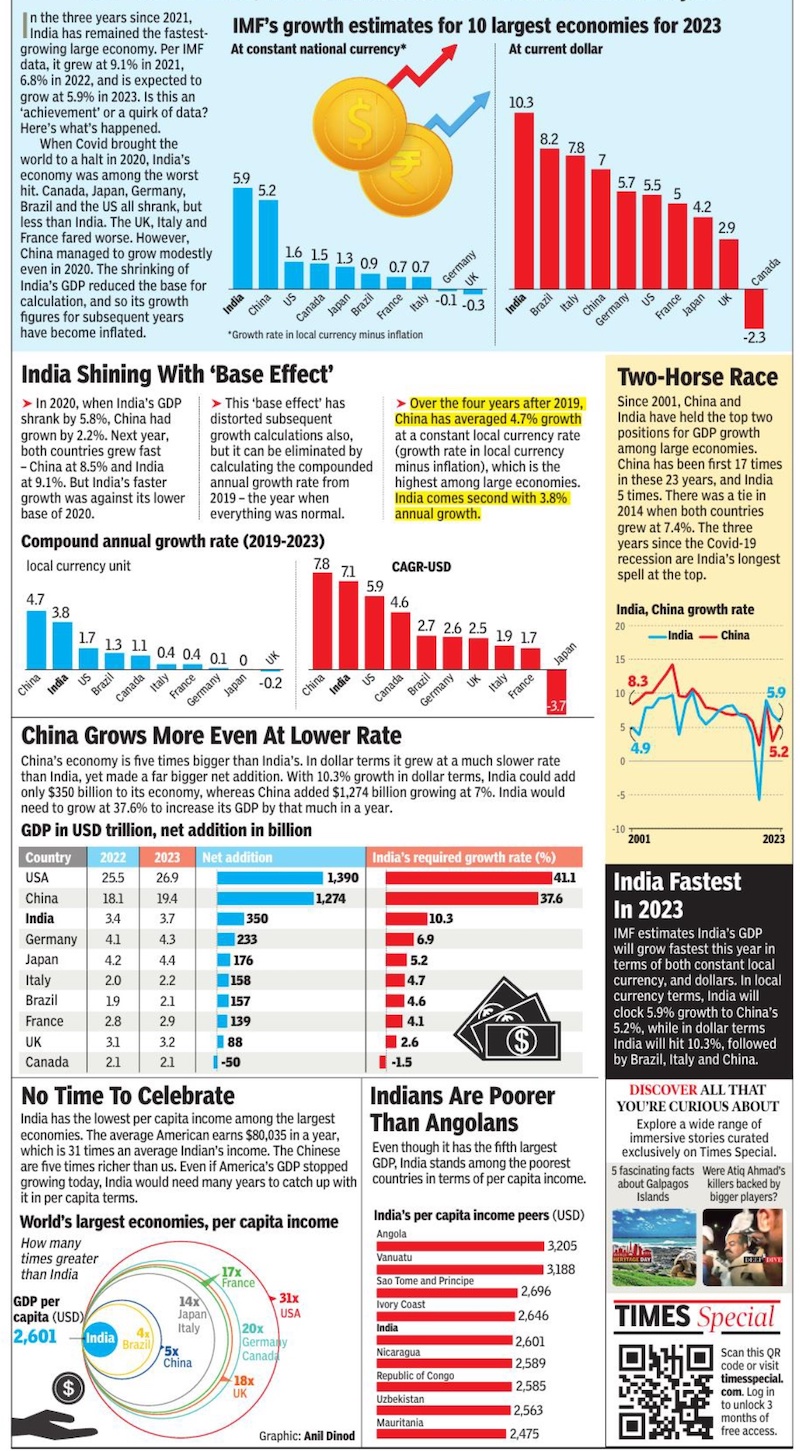

In the three years since 2021, India has remained the fastest growing large economy. Per IMF data, it grew at 9. 1% in 2021, 6. 8% in 2022, and is expected to grow at 5. 9% in 2023. Is this an ‘achievement’ or a quirk of data? Here’s what’s happened.

When Covid brought the world to a halt in 2020, India’s economy was among the worst hit. Canada, Japan, Germany, Brazil and the US all shrank, but less than India. The UK, Italy and France fared worse. However, China managed to grow modestly even in 2020. The shrinking of India’s GDP reduced the base for calculation, and so its growth figures for subsequent years have become inflated.

Electronics

2021, 2023

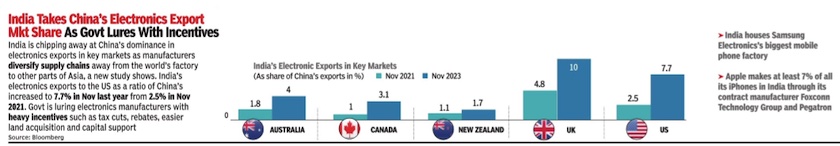

From: February 29, 2024: The Times of India

See graphic:

Exports: India takes China’s Electronics market share, 2021, 2023

FDI

2009-20

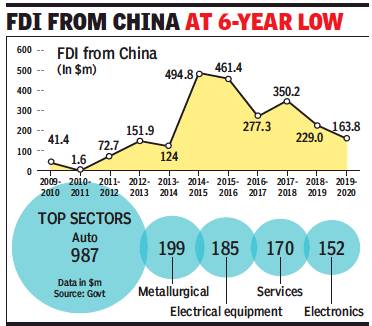

Sidhartha, Little FDI from China since last yr, July 2, 2020: The Times of India

From: Sidhartha, Little FDI from China since last yr, July 2, 2020: The Times of India

New Delhi:

Amid apprehensions of a fall in Chinese investment in India, overall flows added up to just $163 million in 2019-20 and no proposal has been filed since the government decided in April to scan all FDI from countries with which India shares a border. “We have ourselves decided to keep close tabs on Chinese investment, which was meant to discourage them, especially because of the takeover threat for our companies. Without our permission, they can’t invest a single yuan in India,” a government source said.

Officials said some investors may be keen to avoid scrutiny and may be waiting for the detailed clarifications, which will specify things like the definition of “significant beneficial ownership”. The new rules were meant to ensure that Chinese investors do not enter India via a third country.

China accounts for 0.5% of FDI inflows into India

While state-backed Chinese media suggested that FDI inflows will slow down due to Covid-19 as well as the border skirmishes, government officials were, however, dismissive, arguing that China accounts for 0.5% of FDI inflows into India.

Official data showed that China was at number 18 in terms of source of FDI with several other countries such as Singapore and Mauritius ahead of it.

A large number of Chinese investors, such as electronics goods maker Xiaomi, have entered India via Singapore and other countries, which do not reflect in the official numbers. A report by thinktank Gateway House estimated Chinese FDI at around $6.2 billion, with investment in Indian tech companies at around $4 billion. Even at this level, it will be lower than Singapore, Mauritius, US, UK, Germany, Netherlands and Japan, among others.

The official numbers suggest that of the $2.4 billion FDI from China in the last 20 years, close to $1 billion has gone into the auto sector.

Imports from China

Statistics on imports from China

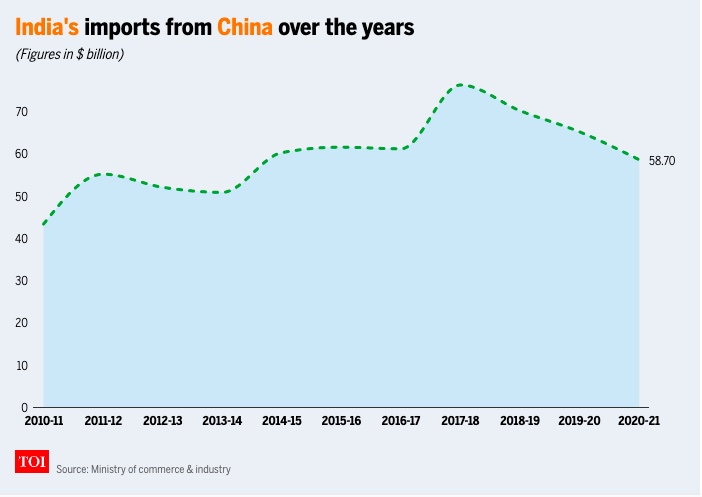

2010-21

March 18, 2021: The Times of India

From: March 18, 2021: The Times of India

From: March 18, 2021: The Times of India

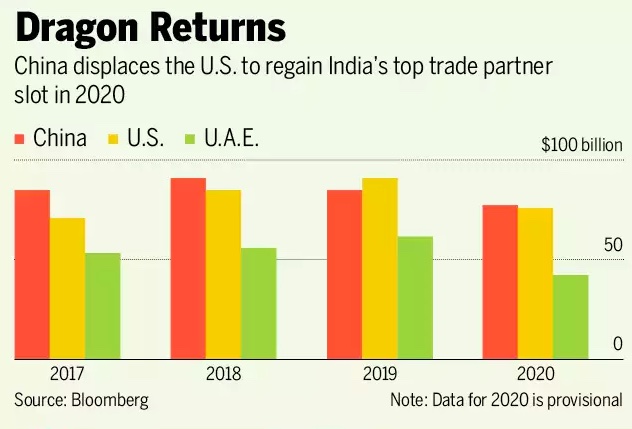

China was India’s top imports source despite LAC crisis

NEW DELHI: Even as most of last year saw Indian and Chinese soldiers engaged in a eyeball-eyeball standoff near LAC in eastern Ladakh and violent clashes between troops in Galwan valley, China continued to remain on top of the list of countries from where India imported goods during January-December, 2020.

In 2020, India imported goods worth $ 58.71 billion from China, MoS (commerce and industry) Hardeep Singh Puri told Lok Sabha in reply to a question by Trinamool Congress MP Mala Roy.

In his written reply, the minister said China, USA, UAE, Saudi Arabia and Iraq were the top five countries (in that order), from where India sourced its imports.

Giving details, the reply said the top five countries from where India imported goods during 2020 (January-December) are China with goods worth $58.71 billion, the US ($26.89 billion), United Arab Emirates ($23.96 billion), Saudi Arab ($17.73 billion) and Iraq ($16.26 billion).

The amount of total imports from the top five countries is worth $ 143.55 billion, which amounts to 38.59 % of the total imports -- amounting to $ 371.98 billion.

The minister also informed the House that, “imports take place to meet the gap between domestic production and supply, consumer demand and preferences for various items”.

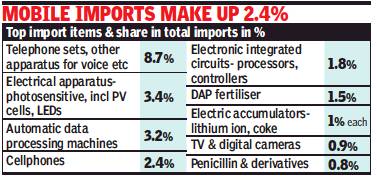

The major items of import from China, according to the minister, were “products such as telecom instruments, computer hardware and peripherals, fertilizers, electronic components/instruments, project goods, organic chemicals, drug intermediates, consumer electronics, electrical machinery etc.”

2018: The main items imported

From: Sidhartha, 327 items form 3/4th of imports from China, ‘can be alternatively sourced’, August 10, 2020: The Times of India

From: Sidhartha, 327 items form 3/4th of imports from China, ‘can be alternatively sourced’, August 10, 2020: The Times of India

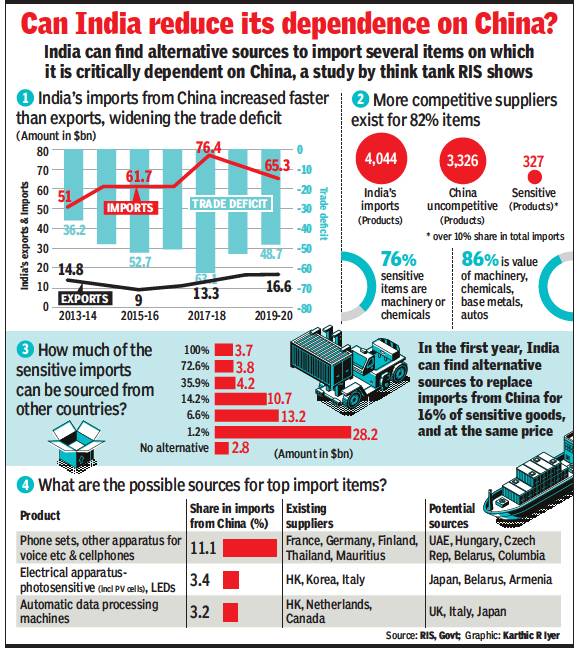

Just 327 products — ranging from mobile phones and telecom equipment to cameras, solar panels, airconditioners and penicillin — accounted for nearly threefourths of the imports from China, a study has estimated, while pointing out that it is possible to find alternative sources to get these goods or manufacture them in India.

A paper by policy thinktank Research and Information System for Developing Countries used UN Comtrade data to estimate the value of these “critically sensitive imports” at $66.6 billion in 2018 in overall imports of a little over $90 billion. In 2018-19, official numbers had pegged imports from China at $76.4 billion.

A product was considered sensitive if China accounted for over 10% share of imports or if the value of shipments was $50 million or more. “Such export monopoly of China has to be diluted in view of strategic requirements,” the report said.

China not the most competitive producer in 82% imports: Study

A product was considered sensitive if China accounted for over 10% share of imports or if the value of shipments was $50 million or more. ‘Such export monopoly of China has to be diluted in view of strategic requirements,” the report by thinktank Research and Information System for Developing Countries said. In FY19, official numbers had pegged imports from China at $76.4 billion.

In terms of the number of goods imported from across the border, the share of the 327 sensitive products was less than 10% of the 4,000-odd items that were imported from China. The study, which was shared with TOI, estimated that in case of 82%, or over 3,300 products, China was not the most competitive producer.

But there are also products where China is the sole exporter. The product base ranges from everyday-use items such as earphones and headphones to microwave ovens and certain types of washing machines. The list also has several types of machinery, some auto components, escalator components, certain acids and chemicals and fertiliser like diammonium phosphate, where China is the sole supplier. “It is possible to produce some of the products domestically if other sources are not immediately available,” RIS director general Sachin Chaturvedi told TOI. The RIS paper suggested taking a strategic view while deciding on alternative sources for imports.

In fact, since March, the government has started tapping overseas missions to identify alternative sources of import of products. Economists and traders, however, point out that it may not be possible to find the products at the same scale, something that even the RIS report points to. “As China is empowered with scale factor, other competitors lose their grounds when delivery of voluminous trade takes place,” the study noted.

In recent years, China has emerged as the hub for the production of electronics, pharma and chemicals with global giants setting up manufacturing facilities to not just cater to the domestic market but export to other destinations, including the US and Europe. Following the outbreak of Covid-19, several companies are looking at de-risking their production chains by setting up or relocating facilities to other countries.

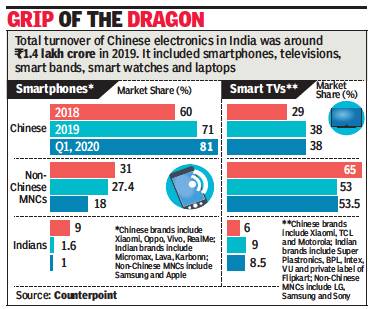

2019: Chinese sold India electronics worth ₹1.4L cr

Pankaj Doval, June 23, 2020: The Times of India

From: Pankaj Doval, June 23, 2020: The Times of India

Even as anti-Chinese sentiment gathers steam across the country, the hold of the dragon on the Indian electronics market remains strong. Chinese companies registered sales of nearly Rs 1.4 lakh crore in the Indian electronics market last year as they dominated the fast-growing categories of smartphones, televisions, laptops, and even smart bands and watches. This has been at the cost of Indian brands such as Micromax, Lava, Intex and Karbonn, and MNCs from countries such as South Korea (Samsung & LG) and Japan (Sony).

In 2019, the Chinese brands closed the year with a share of 71% in the revenue-intensive smartphones category, and this further increased to 81% in the first quarter (January-March) of this year, according to numbers sourced from Counterpoint research.

While Chinese brands such as Xiaomi, Oppo, Vivo and Real-Me strengthened, it was a sad story for the homegrown Indian brands that finished 2019 with only 1.6% share, which further dipped to under 1% in the first quarter of 2020, Prachir Singh, a research analyst at Counterpoint, said.

Such has been the onslaught of the Chinese brands that even the well-entrenched Korean Samsung has been made to play second fiddle, much to its discomfort (as it recently also bid adieu to its business in China). Apple is the only other non-Chinese MNC that does business, but even its share remains marginal.

A Xiaomi spokesperson said, “We witnessed a strong demand for our products during the lockdown and the same is now gradually rising… we continue to ramp up our manufacturing capacities.”

Phones are not the only category that the Chinese are vying for. Finding India to be a willing market, they are fastexpanding into various other categories such as TVs, smart bands, and smart watches. Companies such as Lenovo already hold a significant share in computers.

Does India possess the wherewithal to take on the dragon? “Doubtful,” say most of the players involved in the industry. “The anti-Chinese rhetoric is not a long-term solution. We need a fresh strategy to counter the Chinese, but it will take at least two-to-three years to roll out. Till then, we have to depend on China and there is no other strong alternative,” Pardeep Jain, MD of Jaina group and Karbonn Mobiles, told TOI.

Chinese are also main suppliers of components for phones manufactured in India, and if there is any disruption here, production and new launches will be hit. Navkendar Singh, research director at IDC, said Indian brands lack the profile to stand up to the Chinese. “Without the Chinese, the consumer doesn’t have much choice. In case of any punitive action, consumers and nearly 1.5 lakh multi-brand retailers will be hit.”

Impact of Chinese imports

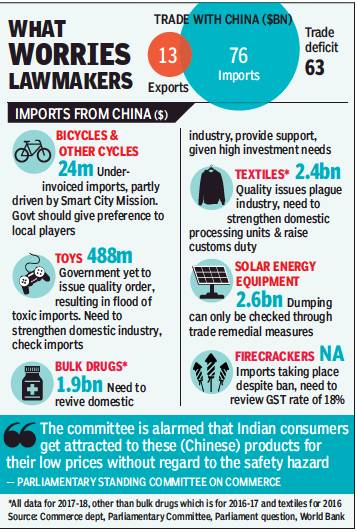

2017-18: Chinese imports shut MSMEs down: Panel

Chinese imports shut MSMEs down: Panel, July 27, 2018: The Times of India

From: Chinese imports shut MSMEs down: Panel, July 27, 2018: The Times of India

Nearly 2L Jobs Lost In Solar Panel Sector

A Parliamentary panel asked the government to swiftly impose quality standards and check Chinese imports across several sectors — from toys and textiles to bulk drugs and bicycles — while noting that shipments from across the border have taken a toll on the domestic manufacturing sector and pushed several micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) to shut shop.

“...India has been an easy dumping ground for Chinese goods on account of low price of Chinese goods, poor enforcement and porous border, both at sea and land,” the standing committee on commerce said in a report tabled in Parliament on Thursday. It said the US and the European Union have been “quite aggressive and agitated over the erosion of their domestic industry and loss of employment” and recommended that the government be more “proactive” in trade defence measures, such as anti-dumping and anti-subsidy actions, while imposing other restrictions.

The panel estimated that dumping of Chinese solar panels in India has resulted in nearly two lakh job losses. Similarly, it pointed out that a large quantity of under-invoiced bicycles were entering the Indian market due to “lax enforcement”. It cited the public bike sharing plan initiated by Smart City administrators as one of the reasons behind surge in shipments from China, which offered cheaper cycles.

Although Chinese goods have traditionally faced the highest anti-dumping action, the committee believes that they are “relatively few in comparison to the kind of dumping” that has taken place. “The impact of Chinese imports has been such that India is threatened to become a country of importers and traders with domestic factories either cutting down their production or shutting down completely,” it said.

Over the last few years, the government too has been worried about the widening trade deficit and is seeking that China open up its markets to more Indian goods to reduce the gap between imports and exports. Rice, meat, pharma and information technology are sectors where the government is seeking greater play for Indian companies in China, which has been reluctant to open up.

The fear of Chinese goods swamping the market has prompted the government to tread carefully on Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership — the proposed free trade agreement involving India, China, Asean countries, Australia and New Zealand.

Besides, other countries have shown little interest in giving Indian software professionals, nurses and other service providers easier access to their markets. In a separate report, the panel slammed some of the provisions of the free trade agreement with Asean, such as services where even the government believes that the treaty is lopsided.

The myth of India buying too much from China/ 2021

Somnath Mukherjee, August 11, 2021: The Times of India

The China import issue, to a large extent, is a bogey. India’s vulnerabilities are far less than is popularly believed. Our responses, therefore, need to be deliberate rather than paranoid, focused on key areas like active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) and rare earth metals

The concept of Group Think was first introduced by psychologist Irving Janis in 1971. He described it as a situation where “individuals tend to refrain from expressing doubts and judgments or disagreeing with the consensus.” While Group Think is widely prevalent in several social contexts, its presence in higher policy-making and inferences can have outsized impact. Perhaps the most well-known example of Group Think in recorded history is the Bay of Pigs invasion. A CIA operation to overthrow the new revolutionary government of Fidel Castro in Cuba, it failed spectacularly and became the showpiece evidence of how groups of smart people rush to consensus without fully analysing the data.

India’s trade dependence on China falls in the same category — the overwhelming consensus in the commentariat is that there is a structural and large import-dependence, one that China can use as a geopolitical weapon in times of sharp political contestations. Headline numbers are trotted out in support — how imports from China have kept going up despite Government of India’s Atmanirbhar campaign and backlash against Chinese goods post-Galwan. There is also a suggestion that China has been able to weaponise its trade surplus with India, using the surplus for enhanced military expenditure while making India “dependent” on Chinese imports for day to day economic life. Most of the hypotheses are in the realm of myths rather than facts.

Myth #1 – India imports too much from China

China is the largest trading nation in the world – its trade volumes with all countries are very high. It is a function of both China’s size as an economy (at $14 trillion, the second largest in the world) as well as its manufacturing prowess. For India, China accounts for 15-16% of aggregate imports (20-21% of non-oil imports). This number is actually lower than many major economies in the world, and most major economies in Asia. US, Australia and Japan — fellow members of the Quad — have more than 20% of their imports originating from China.

India’s import concentration with China, while it went up sharply from 10% in 2010 to 16% in 2017, has stabilised at the latter levels now. For some of the more critical, truly strategic import categories, the trend has either reversed or there is energetic effort underway to reduce dependencies.

Myth 2 –India is dependent on China for imports, creating strategic leverage

This is perhaps the most important hypothesis, meriting closest scrutiny. The largest components of Chinese imports are heavy electricals and machinery, power equipment and organic chemicals. A few trends are quite clear from the chart below.

In absolute terms, the largest category — electrical and electronics goods — are on their way down in absolute terms. The Production Linked Incentive (PLI) programmes rolled out over the last couple of years initially focused largely on this segment, and as capacities under the programme come on stream, the impact is likely to be felt even more. Above all, most of these areas are not “monopoly chokeholds”, i.e, there are alternative sources of supply including domestic, albeit at higher prices. The same holds true for the second largest category of imports – power equipment. Very similar to electricals and electronics, this is an area where China has built a price advantage over global (and Indian) suppliers over the years, and the current dominance is a function of that relative price advantage. A mix of tariff walls, PLI incentives and the US-sponsored global movement of supply chain diversification (popularly termed as China + 1 in trade circles) are creating insurance against China-enforced supply disruptions. Significantly again, China does not have a supply monopoly choke-hold here either – ergo, sourcing from elsewhere is a function of price rather than availability in many cases.

It is the third category — organic chemicals — where things are trickier. It includes active pharmaceutical ingredients (API), the essential intermediate input for a vast majority of pharmaceuticals. China is a dominant global manufacturer of APIs, and this could represent a significant tricky dependence. Till about a decade back, India was self-sufficient in APIs, before much cheaper Chinese capacities drive most pharma companies towards imports. Good news is that there are no great technology hurdles in the segment, merely one of cost and capacity. Already, several Indian companies are investing heavily in the area. Over the next few years, the dependence on China will likely come down. It is actually in a smaller (by absolute $ value) category, rare earth metals, that there are critical strategic issues. China is the source of a range of rare earth metals that are used in critical electronics, telecommunication and other hi-tech equipment. It isn’t an India-specific problem, the world is grappling with the same. The Chinese dominance in the area was sparked off by gradual US withdrawal from mining/processing of rare earth oxides and simultaneous large investments by China. Already, a US-sponsored globally coordinated effort under President Biden’s diversification of supply chain initiative is underway. But this is likely to take time and careful handling by India.

Myth 3 – India’s strategic nirvana would be to cut down on consumer goods production

There is a general (mostly economist wisdom driven) hypothesis that too much of India’s China imports are to fuel elite consumer goods (like cars and mobile phones) and India needs to wean off an economic model that fuels production of such import-intensive consumer goods. This is equivalent of cutting one’s nose to spite one’s face. Industries like automobiles, consumer electronics and mobile phones are not only clusters of large-scale manufacturing employment, they also provide enormous network benefits by spawning entire eco-systems of finance, supply-chain and other related services. They also engender manufacturing exports — small cars, eg, is a rare manufacturing export success story from India. India’s strategic vulnerabilities will rise (and not go lower) in case critical manufacturing bases are hollowed out in an attempt to curb imports. Imports from anywhere, China or otherwise, are not “bad”, and exports of anything is not tautologically “good”. Both are economic transactions with outcomes – the focus has to be on outcomes rather than inputs.

The China import issue, to a large extent, is a bogey. India’s vulnerabilities, as seen above, are far less than is popularly believed. India’s also part of the recent global trend towards de-globalisation, which is actually nothing too different from redundancies in supply chains (which in turn is elementary risk management strategy, forgotten for too long). Our responses, therefore, need to be deliberate rather than paranoid, focused on key areas (like APIs and rare earth metals) rather than looking to up-end all benefits from liberalised trade that have accrued to India since the 1991 reforms. In a nutshell, Groupthink pitfalls need to be zealously avoided!

The author is the Managing Partner and CIO, ASK Wealth Advisors

Indian goods sold in China

2017

HIGHLIGHTS

There is a lot of attraction for Indian foods and many other products all over China.

They are sold by hundreds of Chinese traders through online stores and physical shops.

Almost every city has a shop selling Indian goods, and some like Shanghai, Guangzhou, Yiwu and Beijing have 2-3 each.

Indian masalas are spicing up the Chinese palate like never before with large numbers of them buying Indian food products during the annual shopping event, the Singles Day.

The shopping carnival saw online markets doing business exceeding $30 billion as millions of consumers bought a wide range of goods, most of which are manufactured in China. Some foreign-made goods including those produced in India, Europe and the US were hawked and purchased.

Indian grocery items, ready-made food and Ayurvedic cosmetic brands like Amul, MDH Masala, Gits, Tata Tea, Haldiram, Dabur, Patanjali and Himalaya, were snapped up on Alibaba's Taobao.com, jd.com and several other Internet marketplaces.

The online market attracts a large chunk of the Chinese population with attractive discounts on the occasion, that is also known as 11/11 Singles day+ because it involves the repeated use of 1 or single four times. However, buyers include both married and singles. The 24-hour buying frenzy has emerged as the world's biggest shopping day eclipsing Black Friday and Cyber Monday in the United States.

Alibaba reported that its one-day sales reached $25.35 billion on Saturday, a rise of 39 percent from last year. The company said it had sold goods including apparel, mobile phones, imported lobster and infant formula from 140,000 brands during the day.

JD, which started the discount sales on November 1, said it had sold nearly $20 billion in goods over an 11-day period. It sold 55 million facial masks and 500,000 Thailand black tiger shrimps, JD said. There are several other online shopping firms which have not released all their figures yet.

"There is a lot of attraction for Indian foods and many other products all over China. They are sold by hundreds of Chinese traders through online stores and physical shops. Almost every city in China has a shop selling Indian goods, and some like Shanghai, Guangzhou, Yiwu and Beijing have two or three each," a Guangzhou-based Indian businessman told.

The most sought-after Indian goods are spices followed by cosmetics. Textiles and home decoration pieces are also on sale. Buyers include the vast community of expatriates including Indians, Pakistanis, Japanese, Arabs, Africans and even Europeans who are fond of curried food. More than a million expatriates live in different Chinese cities.

There are more than 100 physical stores selling Indian products in different Chinese cities. These shops, most of whom are run by local traders, also sell online. Indian products usually sell at a premium ranging from 100 percent to 300 percent over the printed prices but this does not deter buyers who want quality products from India.

"The quality of Indian spices like cardamom and cumin seeds is far superior in India as compared to those sold in local Chinese markets. People start realizing it once they use them. Turmeric has become very popular in China," the businessman said.

Chinese have emerged as the world's biggest international travellers, which has resulted in an enlarged worldview and a desire to taste the foods of different countries. Thousands of restaurants in Chinese cities now feature "chicken curry" on the menu. They use ready-made spice mixtures comprising turmeric and other Indian masalas. Many Chinese housewives also cook curry at home.

A wide range of packaged Indian sweets is also on sale at the online markets. They are mostly purchased by foreigners including Arabs, Europeans, and Americans with a sweet tooth because the average Chinese does not have an affinity for intensely sweet eatables.

The Singles Day has also given a boost to China's clout as an international hub for mobile payments and intelligent logistics, the local media quoted Matthew Crabbe, Asia Pacific research director at consultancy Mintel as saying. The Alipay mobile wallet saw deals at a peak rate of 256,000 transactions per second in China and many foreign countries, according to Alibaba. Robots and algorithms accelerated parcel distribution, it said.

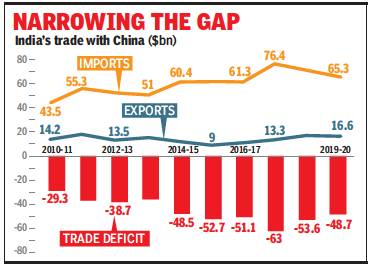

India’s trade deficit

2010-20

June 23, 2020: The Times of India

From: June 23, 2020: The Times of India

India’s trade deficit with China is estimated to have narrowed to $48.7 billion during the last financial year — the lowest in five years — compared with $53.6 billion a year ago, as imports from across the border dropped over 7% to $65 billion in 2019-20.

Last year’s trade deficit was roughly the same as the level seen in 2014-15, when the Narendra Modi administration first took office, but 34% higher than 2013-14, prompting the government to suggest that the steps taken by it in recent months have yielded results.

“It is not as if we are taking steps to reduce imports and reduce the trade gap now. We have been working on strategies for the past several months and going forward the results will be better,” said a source.

Commerce department officials said that the move to opt out of Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RECEP) agreement, the proposed mega free trade agreement, will help it bridge the deficit with other steps such as faster trade remedies against subsidised or dumped goods too coming to the rescue of Indian industry. The fall in imports from China also helped the US extend its lead as India’s largest trading partner. Against trade of $88.8 billion with the US, India’s trade with China was pegged at just under $82 billion.

Power sector

2016-20

NEW DELHI: The government move to keep Chinese companies out of power transmission and distribution (T&D) projects couldn’t have come any sooner. Industry data shows Chinese companies have been making steady inroads into the strategic sector, winning contracts for installing intelligent control systems in parts of the national grid and at least 46 city networks between August 2016 and March this year.

Chengdu-based Dongfang Electric Corporation, one of China’s ‘backbone enterprise groups’ directly administered by Beijing, alone bagged SCADA (supervisory control and data acquisition) contracts for 23 cities across five states and a Union Territory.

ZTT, Shenzen SDG Information Company and Tongguan Group together won 23 contracts from discoms and state-run PowerGrid, which operates the national transmission network, for installing real-time data acquisition system — also known as ‘reliable communication through optical ground wire’.

T&D networks form the backbone of any power system. SCADA and real-time communications systems are the nerve centres that make networks ‘smart’. That’s why sanctity of these systems are important for grid security.

“In connected systems, intelligent equipment talk to each other and exchange data and information, making the system more efficient but at the same time increasing the vulnerability if exposed to suspect individuals, companies and nations which may use such access to their advantage,” Indian Electrical Equipment Manufacturers’ Association director-general Sunil Misra told TOI.

The power ministry had on July 3 banned equipment imports from China without permission. It also mandated imported T&D equipment be tested at designated laboratories for embedded malware or spyware — a common perception about Chinese gear.

The move, even though part of economic retaliation against China’s border transgressions in Ladakh, marked an acknowledgement of possible vulnerabilities with Chinese equipment.

IEEMA had written to the national security adviser and the ministry in 2017 to point out India’s transmission system becoming vulnerable to hacking due to expanding Chinese footprint.

Later that year, the state power ministers conference decided to conduct a countrywide cyber security audit of T&D systems.

These warnings followed protests over Chinese companies bagging a slew of big-ticket contracts for power station hardware as India rushed to ramp up generation capacity.

Rice from India

2020: China buys Indian rice for first time in decades

Reuters, December 2, 2020: The Times of India

China buys Indian rice for first time in decades as supplies tighten: Trade officials

MUMBAI: China has started importing Indian rice for the first time in at least three decades due to tightening supplies and an offer from India of sharply discounted prices, Indian industry officials told Reuters.

India is the world's biggest exporter of rice and China is the biggest importer. Beijing imports around 4 million tonnes of rice annually but has avoided purchases from India, citing quality issues. The breakthrough comes at a time when political tensions between the two countries are high because of a border dispute in the Himalayas.

"For the first time China has made rice purchases. They may increase buying next year after seeing the quality of Indian crop," said B V Krishna Rao, president of the Rice Exporters Association.

Indian traders have contracted to export 100,000 tonnes of broken rice for Dec-February shipments at around $300 per tonne, industry officials said.

China's traditional suppliers, such as Thailand, Vietnam, Myanmar and Pakistan, have limited surplus supplies for export and were quoting at least $30 per tonne more compared with Indian prices, according to Indian rice trade officials.

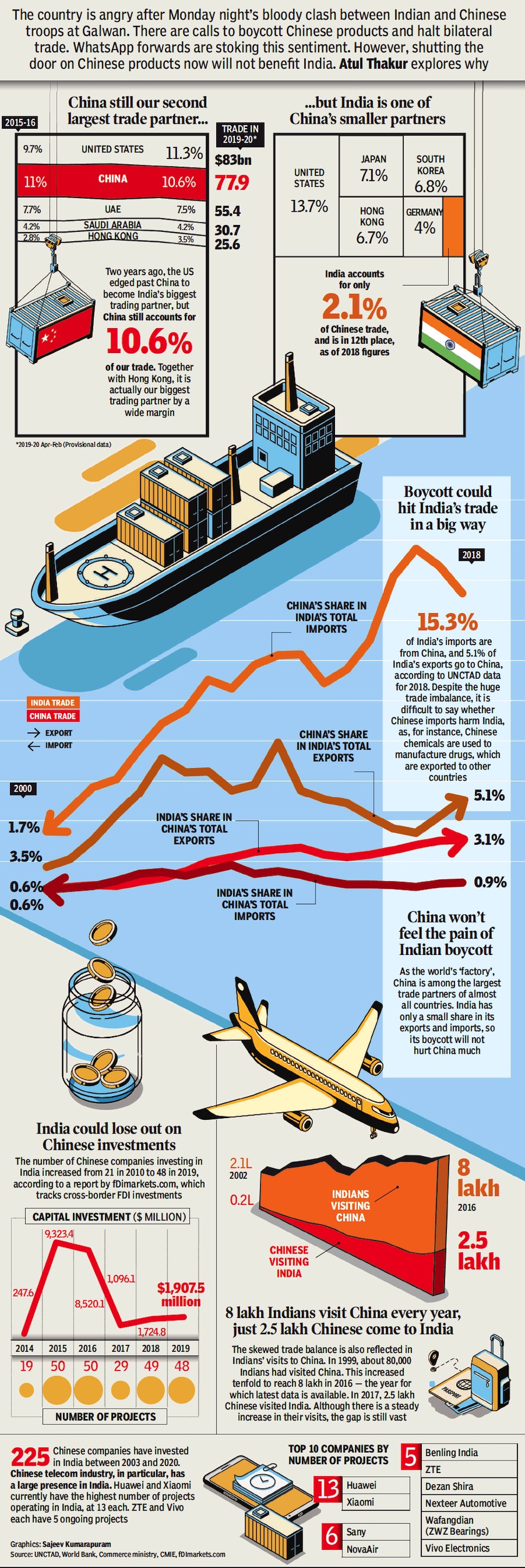

Year-wise statistics

2019

From: June 20, 2020: The Times of India

See graphic:

An overview of China- India economic relations, as in 2019.

2020

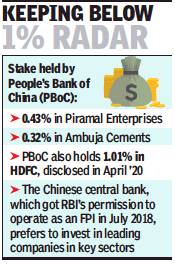

China's central bank buys stakes in Indian companies

From: July 7, 2020: The Times of India

In mid-April, stock exchange disclosures revealed that the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) had a holding of over 1% in Indian mortgage finance major HDFC. But the Chinese central bank also holds stakes in several other listed companies. However, these are all below the radar since they are less than the 1% threshold limit for open disclosures by companies (see graphic).

PBoC’s holding in HDFC is worth about Rs 3,100 crore, while in Piramal Enterprises around Rs 137 crore, and in Ambuja Cement about Rs 122 crore. Exactly two years ago, the Chinese central bank had received RBI permission to set shop here. Two recent reports on Chinese investments in India have warned that several funds and investment companies, directly controlled or indirectly influenced by its government, have been eyeing stakes in companies that are strategically important to the economy.

Market sources said the Chinese central bank also has stakes in the Indian arm of a German manufacturing major and another domestic fertilisers major. But these are not disclosed publicly since all they are below the 1% limit.

After PBoC’s stake acquisition in HDFC came to light on April 12, the government, through a press note on April 17, amended foreign investment rules into India. According to a leading Sinologist, there is an old Chinese tactic called “loot a burning house”. “The government policymakers should remember this while formulating the FDI policies.”

A recent Brookings Institute report also put out caveats along similar lines for Indian policymakers. “Chinese companies are emerging as prominent players and investors,” Ananth Krishnan, the author of the report, said. Drawing on several sources within India and from China, the report said that the aggregate Chinese investment in India was a staggering $26 billion with a pledge to invest another $15 billion. However, these figures are likely an underestimation, given the reluctance of the Chinese government to share the data.

Another report by Gateway House, a foreign relations think tank, pointed out how Chinese companies were using the startup route to invest in leading players in several sectors in India.

See also

China-India relations: 1899-01

China-India relations: 1900-1999