Demonetisation of high value currency- 1946, 1978: India

The Times of India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Related pages on Indpaedia

Demonetisation of high value currency- 2016: India

Demonetisation of high value currency- 1946, 1978: India

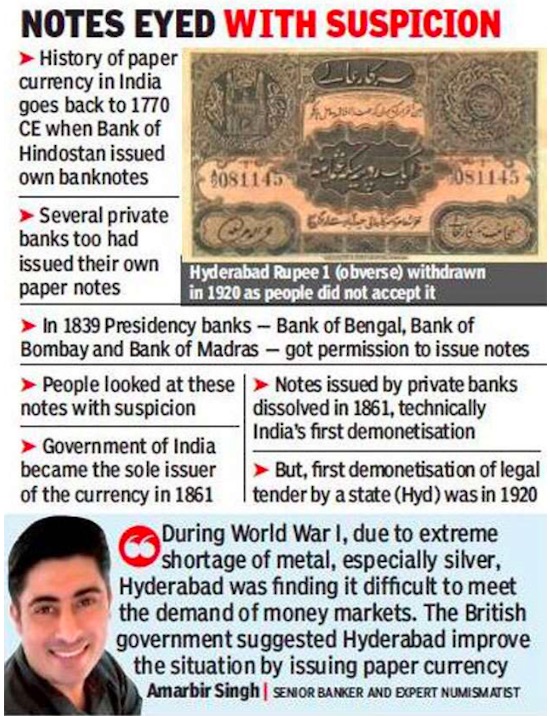

1861,1920

Briefly

India’s first demonetisation, a 100 years ago in Hyderabad , February 2, 2020: The Times of India

From: India’s first demonetisation, a 100 years ago in Hyderabad , February 2, 2020: The Times of India

From: India’s first demonetisation, a 100 years ago in Hyderabad , February 2, 2020: The Times of India

HYDERABAD: India's first demonetisation of paper currency- It was in 1920 that the Nizam government in Hyderabad had withdrawn Rupee 1 paper currency from circulation. The Nizam had introduced Rs 10 and Rs 100 paper currency in 1918 and Rupee 1 in 1919 as there was severe shortage of metal particularly silver in view of the World War I.

There were, however, no takers for the Rupee 1 note as it had no intrinsic value though backed by a government guarantee, while Rupee 1 silver coin, which was in circulation then, had intrinsic value as it had silver in weight.

Moreover, the Rupee 1 note was printed in black. People saw the colour as inauspicious and thus refused to accept it. This forced the Nizam to withdraw the note within one year of its introduction, heralding India's first demonetisation.

According to senior banker and expert numismatist Amarbir Singh, the British government had conferred on the princely state of Hyderabad the right to mint its own coins. "During World War I, due to extreme shortage of metal, especially silver, Hyderabad was finding it difficult to meet the demand of money markets. The British government suggested that Hyderabad improve the situation by issuing paper currency. This resulted in the Hyderabad Currency Act 1917/1918 which got Nizam VII, Mir Osman Ali Khan's assent on June 4, 1918," he said.

In 1861, the British government became the sole issuer of paper currency and all private banks, which had their own banknotes, were directed to withdraw them. But the first legal tender (Re 1) issued by a government (Hyderabad state) was withdrawn in 1920, thus officially the first demonetisation drive.

The Nizam issued Re 1 and Rs 5 banknotes in 1919. Later, he issued Rs 1,000 banknote in 1926. The withdrawn currency was kept in the royal treasury and destroyed in March 1939. However, about 8,500 notes remained with the public. Waterlow, which had the contract to print money, had printed two crore notes. During transit, 608 notes were stolen in Bombay. The government destroyed 20.92 lakh notes which were in circulation. Another 1,78,98,642 notes, which were not issued, were also destroyed, Amarbir said, adding that while five notes were kept as souvenirs in the mint, 245 were preserved in the central treasury of the Nizam.

He said soon after the Nizam government destroyed Re 1 notes, World War II began in September 1939, once again creating shortage of metal, and the need to reintroduce Re 1 note arose. Security press at Nasik turned down the request to print Re 1notes citing circumstances beyond its control. This led to the birth of ‘made in Hyderabad’ Re 1 as the new notes were printed at government press in Malakpet.

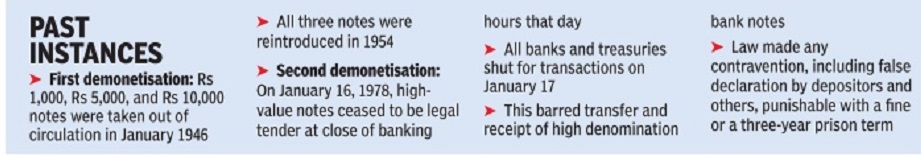

1946

See graphic for the broad outline. The Mehta Parikh case study is only for historians and Income Tax lawyers. Lay readers may skip it.

What happened in 1946

In West Bengal, a pundit had to postpone the marriage of his daughter. The Rs 1,000 notes he had scraped together for the marriage were no longer legal tender.

In Nainital a big businessman fell over and died from heart failure when he went to hand in his Rs 1,000 notes. And in Calcutta, an enterprising gentleman who handed in notes to the value of Rs 6.03 lakh, the largest amount deposited that day, claimed he had got them for “an official secret which could not be disclosed to the public.”

These stories are from on January 12, 1946, when the pre-Independence government of India passed the High Denomination Bank Notes (Demonetisation) Ordinance. The background was World War II, which had just got over, but during which businessmen in India were supposed to have made huge fortunes supplying the Allied war effort and were concealing their profits from the tax department.

Letter writers to the Times of India (ToI) exulted at this first formal demonetisation in India. “The money that is concentrated in the hands of these people is not simply wealth. It is the life blood of thousands of Indians who starved and died during the last five years while black marketeers went on piling up money in their safes,” fumed SR Rangnekar from Bombay (now Mumbai). He advised the government to follow this up by cracking down on their stocks of gold “if they exceed 100 tolas.”

G Pingle from Kalyan noted snidely that many black marketing businessmen “tried to play the role of true nationalists. It passes my comprehension why so-called nationalists did not make any attempt to improve the condition of their war-weary fellow men.” Eric Miranda from Bandra suggested that people handing in high-value notes “might even be allowed to smoke a cigarette made out of one of these notes, as some are now doing, as some consolation.”

A writer using the name Non-Idealist suggested, more practically, that the government not waste time moralising about the black market, but just focus on getting the money. Noting that a large amount of notes might just never get handed in because they could not be accounted for, and hence go to waste (or be used to make cigarettes), the writer suggested the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) simply offer 30-40% of the value of the notes, with no questions asked.

The Indian nationalist leaders, who hadn’t been party to the decision, sounded dubious about its effects. Rajendra Prasad, who would become the first president of India, declared that “while we, Congressmen, have no sympathy with profiteers and dealers in the black market, it is not right to penalise honest people who in good faith have their savings in notes of demonetised value… A large number of people belonging to the middle and lower middle classes will be hit hard.”

And in a display of scepticism about government regulations that, sadly, would not carry over to the later Indian government, Prasad wondered how the problem had been created in the first place: “Many of the wartime ordinances succeeded in complicating the problems which they were intended to solve and in creating opportunities for corruption. The new ordinances are not going to fare any better.”

The similarity of all these reactions, from the fulminations of letter writers (Net commentators today), to the need for a mysterious, corrupt group to blame, to concerns for the impact on regular people, all suggest that there is something cyclical about demonetisation. Even the secrecy with which the current government pulled it off has parallels in 1946. “Never was a secret so well kept in Delhi,” wrote ToI on January 26. Even government officials were left with high-value notes to hand in.

ToI wrote that only eight officials knew about the plan, including the RBI governor and the finance member of the Viceroy’s Council (the equivalent of today’s finance minister). “In order to be issued on Saturday, January 12, the ordinance had to be flown in a special plane to Poona for the Viceroy’s signature. It was then flown back.”

During the discussions with governor Chintaman Deshmukh (later to be Nehru’s finance minister), the officers took notes and typed drafts themselves, without the help of secretaries. “Handwritten notes exchanged between these officials were carefully burnt. No carbon copy of the documents was made or kept.” Even extra staff wasn’t allocated to the RBI’s currency department just in case that raised suspicions.

The collections made justified the precautions. ToI reported that currency notes to the value of Rs 47 crore had been deposited across India, with Bombay in the lead with Rs 27 crore, followed by Calcutta (now Kolkata) with Rs 7 crore, Karachi with Rs 3 crore, Lahore with Rs 2.5 crore and Madras (now Chennai) with Rs 60 lakhs. New Delhi, as a newly constructed government town, didn’t seem to count at all. The Indian princes weren’t exempt, but were allowed to use a special form approved by the crown representative in their state.

For a while after 1946, black money ceased to be a major issue. The demonetisations that took place were technical, dealing with the currencies of the native states. In 1949, for example, Kutch’s koris were converted; they were pure silver and were causing problems in the bullion market. After the takeover of Hyderabad, the Osmania sicca, a 148-year-old currency, was converted to Indian rupees in 1957, with a grace period of two years for the change. In 1963-64 the old annas and pice coins were converted to paise, also a technical demonetisation.

But around that time, the rumours about black money started rising again. In 1965, finance minister TT Krishnamachari had to face questioning from increasingly assertive opposition members about the quantum of black money, and using demonetisation to stop it (high-value notes came back in 1954).

1965- 1972

On April 20, 1965, Krishnamachari replied in Parliament that “demonetisation was neither feasible nor would produce results.” He felt that estimates of black money were hugely over inflated and what did exist had been converted to “bonds, property and shares,” all beyond the reach of demonetisation.

Yet the demand never went away. In 1970, it got a boost of sorts when neighbouring Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) conducted a truly radical demonetisation that extended to Rs 100 and Rs 50 notes. A commission on direct taxation was set up under Justice Kailas Nath Wanchoo that looked at the issue and, perhaps inspired by Ceylon, it suggested even demonetising down to Rs 10 notes!

This seems to have been more on the lines of what will happen with our current Rs 500s, where the denomination still exists, but the physical notes will change. As Prem Shankar Jha noted in a column in ToI on August 28, 1972, this in itself would have required a major feat: “The government will have to print no less than 3,500 million currency notes – at least ten times as many as in a normal year – and transport them to every treasury office, bank and post office in the country.” It would, he pointed out, be impossible to do this secretly.

In a sign of the rising demand for action though, Jha concluded his piece by suggesting that, despite the logistical problems, it was needed as a scare: “The real value of demonetisation lies in its therapeutic effect on the economy. Large numbers of habitual tax evaders conceal their incomes only because years of laxity and permissiveness in the present tax laws have lulled them into a sense of security.”

There is an echo here of [the 2016] Prime Minister [Mr Modi]’s speech, urging India to accept the short-term pain for the long-term, cleansing effect. And it shouldn’t be a surprise that later that same year the Jan Sangh, the precursor to the Bharatiya Janata Party, adopted demonetisation in a resolution at a party conference in Jaipur. “The resolution said between high prices and high taxes the citizen was being ‘crushed’,” wrote ToI, and one can see an argument that the flow of black money was causing the first and was caused by the latter.

1978

So when Janata came to power, with the Jan Sangh as part of the coalition, demonetisation was always likely to be on the agenda. Again, it was put into effect with speed and secrecy. According to the RBI’s official history, on January 14, 1978, R Janakiraman, a senior RBI official was asked to go to Delhi on “some urgent work.” Despite being told to go alone, he took an assistant and when they reached they were told they had 24 hours in which to draft a demonetisation ordinance.

They were forbidden from communicating with RBI headquarters in Bombay. They managed to get a copy of the 1946 ordinance and used it to draft a new one. On January 16 it was announced that Rs 1,000, Rs 5,000 and Rs 10,000 notes were being withdrawn from circulation. As with Modi’s announcement on November 8, the next day was declared a public holiday to allow banks to prepare for the onslaught. The public was given just three days to exchange their notes.

Long queues formed in front of RBI and State Bank of India offices from very early in the morning. Additional counters were set up but, according to the RBI history, January 18 “started with utter confusion over the issue of declaration forms at the Reserve Bank headquarters at Bombay and working hours were stretched to 6.30 pm.” Tempers rose and there was a particular outcry from foreign tourists who faced the prospect of running out of legal money far from home.

Despite the problems, finance minister HM Patel declared he was pleased. ToI quoted him saying, a bit cryptically, “You will see me smiling whatever the result.” He deflected suggestions that it would harm trade and industry by saying the measure “would affect smugglers who were in any case on the fringes of trade and industry.” Rather oddly, he played down the impact on black money since, for that, he said it would have been necessary to demonetise Rs 100 notes. This measure, he said, was just to reduce the money used in illegal transactions.

If the finance minister was vague, RBI governor IG Patel was not. In his memoirs, Glimpses of Indian Economic Policy, he made clear he went along with demonetisation reluctantly. He had pointed out to the finance minister that “such an exercise seldom produces striking results.” People who have black money on a substantial scale rarely keep it in cash. “The idea that black money or wealth is held in the form of notes tucked away in suit cases or pillow cases is naïve.” Patel pointed out that even those who are caught with black money can usually find agents who will convert the notes through a number of small transactions “for which explanations cannot be reasonably sought.” Yet the government was insistent, and so “the gesture had to be made, and produced much work and little gain.” Patel didn’t mention it, but another former finance minister C Subramaniam suggested that, then as now, the real aim was political and aimed against other parties.

The same point was made by two economists--CN Vakil and PR Brahmananda. They pointed out that the measure might have had some merit if it had reduced money supply, perhaps by exchanging the notes for a little less. As it stood it was just “a publicity boost” to the government and they recalled how the 1946 demonetisation had just resulted in Rs 10 crore going out of the circulation and the recent Sri Lankan experiment had much the same impact: “One guess is that the present measure has primarily a political and not economic objective. In such a case it becomes a business in and among politicians.”

The rapidity with which black money became an issue again in following decades suggests that the doubters had a point. Perhaps demonetisation is always more of a political gimmick. Perhaps, as Jha had suggested, it is a needed warning to discourage black marketers – though as the doubters might argue, the question remains if the really big players are affected, while regular people suffer the pain.

Excerpt from The Reserve Bank of India’s history

The entire relevant chapter has been excerpted below

CURRENCY AND COINAGE MATTERS

In regard to currency, two developments have to be recorded. The first, the demonetisation of high denomination notes, was a fiscal measure, taken against the Bank’s advice. The second was the replacement of silver coinage by nickel, the Bank lending strong and active support to the change-over.

Demonetisation of High Denomination Notes

Soon after the war, while Government were giving attention to ways and means of averting the expected slump, thought was also given to check black market operations and tax evasion, which were known to have occurred on a considerable scale. Following the action in several foreign countries, including France, Belgium and the U.K., the Government of India decided on demonetisation of high denomination notes, in January 1946. It is interesting that as early as April 7, 1945, in an editorial on the tasks before the new Finance Member, Sir Archibald Rowlands, the Indian Finance referred to the action of the Bank of England in calling in notes of ₤ 10 and higher denominations and suggested similar action in India as ‘one more concrete example for the Indian Government to follow in its fight against black market money and tax evasions which have now assumed enormous proportions ‘.

It is not known when the Government authorities started thinking on the demonetisation measure, but the final consultation with the Governor and Deputy Governor Trevor took place towards the end of 1945, when Mr. N. Sundaresan, Joint Secretary, Ministry of Finance, called for a discussion, for which he had earlier prepared a note and the drafts of the Ordinances to implement the scheme. According to a note recorded by Mr. Sundaresan, it would appear that the Reserve Bank authorities were not enthusiastic about the scheme.

The Governor stated that the Finance Member had given him the impression that the scheme would be launched only when there were signs of the onset of an inflationary spiral. The Governor saw no special signs of such a situation. ‘It appeared to him that the main object of the scheme was to get hold of the tax evader. The Governor wondered if this could be called an emergency to justify the promulgation of an Ordinance, just before the newly elected Legislative Assembly met. The Governor wanted Government to be satisfied that there was no harassment to honest persons. As a currency authority, the Bank could not endorse any measure likely to undermine the confidence in the country’s currency.

The Governor agreed that about 60 per cent of the notes would be in the Indian States and so co-operation of the State Governments was very necessary. Apparently he had some doubts about this. According to Mr. Sundaresan, the ideal thing was to block high denomination notes, but this course was not favoured by either the Finance Member or the Governor.

Subject to these observations, the scheme as drafted by Mr. Sundaresan was considered by the Governor to be theoretically all right, but he and the Deputy Governor pointed out the considerable administrative difficulties involved in covering nearly 5,700 offices of scheduled and non-scheduled banks. The Governor’s concluding remarks, as recorded by Mr. Sundaresan, were as under:

Sir Chintaman Deshmukh felt that we may not get even as much as Rs. 10 crores as additional tax revenue from tax evasion and that the contemplated measure, if designed to-achieve such a purpose, has no precedent or parallel anywhere. If value is going to be paid for value (no matter whether such value is in lower denomination notes), it is not going to obliterate black markets. His advice is that we should think very seriously if for the object in view (as he deduces from the declaration form) whether this is an opportune time to proceed with the scheme. Provided Government are satisfied on the points of (i) sparing harassment to the unoffending holders and (ii) a worthwhile minimum of results in the shape of extra tax revenue, he does not wish to object to the scheme as drafted, if Government wish to proceed with it notwithstanding the administrative difficulties involved.

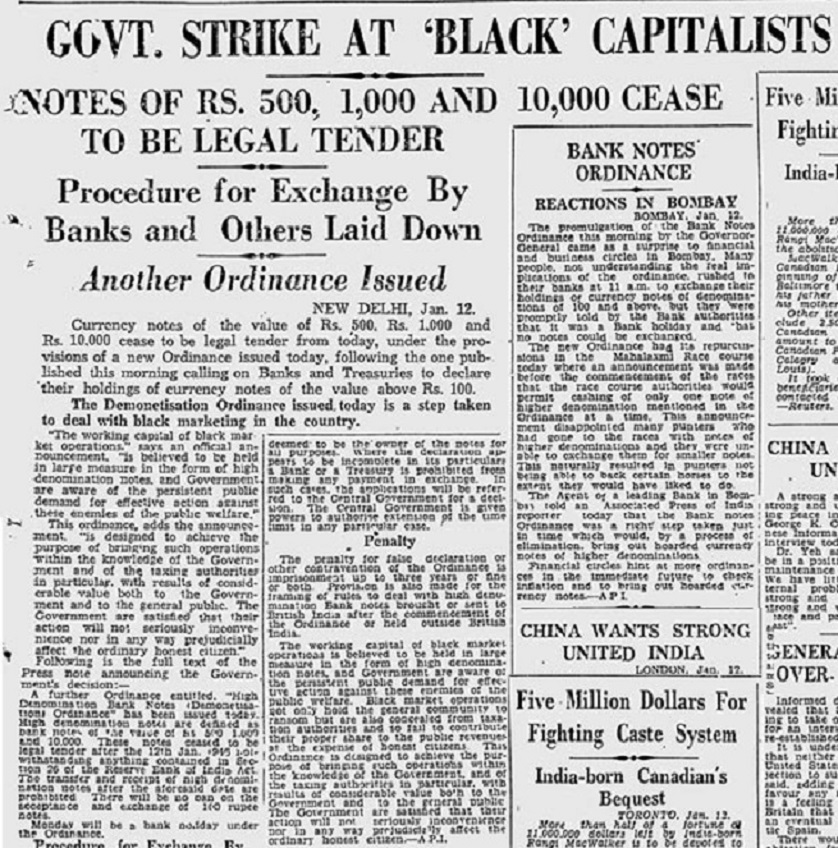

The Government went ahead with the scheme. On January 12, 1946, two Ordinances were issued, demonetizing notes of the denominational value of Rs. 500 and above. The first Ordinance, viz., the Bank Notes (Declaration of Holdings) 0rdinance, 1946, required all banks and Government Treasuries in British India to furnish to the Reserve Bank of India by 3 p.m. on the same day, a statement of their holdings of bank notes of Rs.100, Rs. 500, Rs. 1,000 and Rs.10,000 as at the close of business on the previous day. January 12, 1946 was declared a bank holiday. The second, the High Denomination Bank Notes (Demonetisation) Ordinance, 1946, demonetised bank notes of the denominations of Rs. 500 and above with effect from the expiry of January 12, 1946.

This Ordinance provided that a non-scheduled bank could exchange high denomination notes declared by it under the Bank Notes (Declaration of Holdings) Ordinance at the Reserve Bank or a scheduled bank, for value in one hundred rupee notes or for credits with the Reserve Bank or a scheduled bank. Scheduled banks and Government Treasuries could obtain from the Reserve Bank value in one hundred rupee notes or in deposits with the Reserve Bank in exchange for high denomination notes declared by them under the above mentioned Ordinance. Other holders of high denomination notes could get them exchanged at the Reserve Bank, a scheduled bank or a Government Treasury on presentation of the high denomination notes and a declaration in the form prescribed in the schedule to the Ordinance, within 10 days of the commencement of the Ordinance.

Under a press note issued subsequently by the Government of India on January 26, 1946, Managers and Officers in charge of offices and branches of the Reserve Bank of India were authorised to allow exchange of high denomination notes, up to and inclusive of February 9, 1946, on production of sufficient and valid reasons for delay in the presentation of notes. Thereafter the Governor and the Deputy Governor of the Bank were authorised to allow exchanges up to and inclusive of April 26, 1946. The power for the extension of the time limit beyond April 26, 1946 was reserved for the Government of India

The provisions of the second Ordinance, which was applicable to British India, were also extended, with suitable modifications, to the Administered Areas on January 22, 1946. Many Indian States also issued parallel Ordinances. States which did not enact such legislation were required to exchange their holdings of demonetised notes before March 7, 1946.

The measure did not succeed, as by the end of 1947, out of a total issue of Rs. 143.97 crores of the high denomination notes, notes of the value of Rs. 134.9 crores were exchanged. Thus, notes worth only Rs. 9.07 crores were probably ‘demonetised ‘, not having been presented. The results of the demonetisation measure were summed up by Sir Chintaman, in his Dadabhai Naoroji Memorial Prize Fund Lectures, delivered at Bombay in February 1957, as under :

It was really not a revolutionary measure and even its purpose as a minatory and punitive gesture towards black-marketing was not effectively served. There was no fool-proof administrative method by which a particular note brought by an individual could be proved as the life-savings of the hard-working man who presented it or established as the sordid gains of a black-marketer. Another loophole of which considerable advantage was taken was the exemption of the princely States from scrutiny or questioning when such notes were presented by them. In the end, out of a total issue of Rs.143.97 crores, notes of the value of Rs.134.9 crores were exchanged up to the end of 1947 as mentioned in the Report of the Board of Directors of the Reserve Bank. Thus, notes worth only Rs.9.07 crores were probably “‘demonetised “, not having been presented. It was more of “conversion “, at varying rates of profits and losses than “demonetisation “.

There was an echo of this measure in 1948. In September, while Government were considering anti-inflationary measures, rumours spread that the 100 rupee notes would be demonetised and that bank deposits would be frozen. The Prime Minister had to make a statement in the Legislature, categorically denying any such intentions on the part of Government.

In 1946, too, IT officers smelt black money in high notes

The Mehta Parikh case study is mainly for historians and Income Tax lawyers. Lay readers may skip it.

In 1946, too, many rich Indians had black money as in 1978 and 2016. Even then they claimed that Income Tax officers were harassing them. Take this case that was heard in the courts from 1946 to 1956.

Messrs Mehta Parikh & Co vs The Commissioner Of [Income Tax?] on 10 May, 1956 Indian Kanoon

The appellants were a partnership firm doing business in Mill Stores at Ahmedabad. Their head office was in Ahmedabad and their branch office in Bombay.

The Governor-General on 12th January 1946 promulgated the High Denomination Bank Notes (Demonetisation) Ordinance, 1946 and high denomination bank notes ceased to be legal tender on the expiry of 12th day of January 1946.

Pursuant to clause 6 of the Ordinance the appellants on 18th January 1946 encashed high denomination notes of Rs. 1,000 each of the face value of Rs. 61,000 [at least Rs.61 lakh at 2016 prices].

During the assessment proceedings for the year 1947-48 the Income-tax Officer called upon the appellant to prove from whom and when the said high denomination notes of Rs. 61,000 were received by the appellants and also the bona fides of the previous owners thereof. After examining the entries in the books of account of the appellants and the position of the Cash Balances on various dates from 20th December 1945 to 18th January 1946 and the nature and extent of the receipts and payments during the relevant period, the Income-tax Officer came to the conclusion that in order to sustain the contention of the appellants he would have to presume that there were 18 high denomination notes of Rs. 1,000 each in the Cash Balance on 1st January 1946 and that all cash receipts after 1st January 1946 and before 13th January 1946 were received in currency notes of Rs. 1,000 each, a presumption which he found impossible to make in the absence of any evidence. He, therefore, added the sum of Rs. 61,000 to the assessable income of the appellants from undisclosed sources.

The cash book entries from 20th December 1945 up to 18th January 1946 were put in before the Income-tax Officer and they showed that on 28th December 1945 Rs. 20,000 were received from the Anand Textiles, and there was an opening balance of Rs. 18,395 on 2nd January 1946. Rs. 15,000 were received by the appellants on 7th January 1946 from the Sushico Textiles and Rs. 8,500 were received by them on 8th January 1946 from Manihen, widow of Shah Maneklal Nihalchand. Various other sums were also received by the appellants from 2nd January 1946 up to and inclusive of 1 1 th January 1946, which were either multiples of Rs. 1,000 or were over Rs. 1,000 and were thus capable of having been paid to the appellants in high denomination notes of Rs. 1,000. There was a cash balance of Rs. 69,891-2-6 with the appellants on 12th January 1946, when the High Denomination Bank Notes (Demonetisation) Ordinance 1946 was promulgated and it was the case of the appellants that they had then in their custody and possession 61 high denomination notes of Rs. 13000, which they encashed through the Eastern Bank, on 18th January 1946. The appellants further sought to support their contention by procuring before the Appellate Assistant Commissioner the affidavits of Kuthpady Shyama Shetty, General Manager of Messrs Shree Anand Textiles, in regard to payment to the appellant is of a sum of Rs. 20,000 in Rs. 1,000 currency notes on 28th December 1945, Govindprasad Ramjivan Nivetia, proprietor of Messrs Shusiko Textiles, in regard to payment to the appellants of a sum of Rs. 15,000 in Rs. 1,000 currency notes on 6th January 1946 and Bai Maniben, widow of Shah Maneklal Nihalchand, in regard to payment to the appellants of a sum of Rs. 8,500 (Rs. 8,000 thereout being in Rs. 1,000 currency notes) on 8th January 1946. The appellants were not in a position to give further particulars of Rs. 1,000 currency notes received by them during the relevant period, as they were not in the habit of noting these particulars in their cash book -and therefore relied upon the position as it could be spelt out of the entries in their cash book coupled with these affidavits in order to show that on 12th January 1946 they had in their cash balance of Rs. 69,891-2-6, the 61 high denomination currency notes of Rs. 1,000 each, which they encashed on 18th January 1946 through the Eastern Bank. Both the Income-tax Officer and the Appellate Assistant Commissioner discounted this suggestion of -the appellants by holding that it was impossible that the appellants had on hand on 12th January 1946, the 61 high denomination currency notes of Rs. 1,000 each, included in their cash balance of Rs. 69,891-2-6. The calculations., which they made involved taking into account all payments received by the appellants from and after 2nd January 1946, which were either multiples of Rs. 1,000 or were over Rs. 1,000. There was a cash balance of Rs. 18,395-6-6 on band on 2nd January 1946, which could have accounted for 18 such notes. The appellants received thereafter as shown in their cash book several sums of monies aggregating to over Rs. 45,000 in multiples of Rs. 1,000 or sums over Rs. 1,000, which could account for 45 other notes of that high denomination, thus making up 63 currency notes of the high denomination of Rs. 1,000 and these 61 currency notes of Rs. 1,000 each, which the appellants encashed on 18th January 1946 could as well have been in their custody on 12th January 1946. This was, however, considered impossible by both the Income-tax Officer and the Appellate Assistant Commissioner as they could not consider it within the bounds of possibility that each and every .payment received by the appellants after 2nd January 1946 in multiples of Rs. 1,000 or over Rs. 1,000 was received by the appellants in high denomination notes of Rs. 1,000 each.' It was by reason of their visualisation of such an impossibility that they negatived the appellants' contention.

1978

Surprise & panic: History repeats itself 38 yrs later, Nov 09 2016 : The Times of India

Summary

2016 was not the first time high value currency notes were demonetised.

In January 1978, the Morarji Desai-led Janata Party government had demonitised Rs 1,000, Rs 5,000 and Rs 10,000 notes to curb black money .This was less than a year after the Emergency was lifted.

Old-timers remember that the decision then too had taken the public by surprise, leading to panic and a rush to banks although people were given time to exchange old notes.

To put things in perspective, a Rs 1,000 note in 1978 could buy 5 sq ft of real estate space in south Mumbai. In 2016, a Rs 500 note would not even be worth 100th of a square foot.

Senior advocate Anil Harish said people with unaccounted money were reluctant to deposit their high denomination currency in banks because of fear of income tax sleuths. “At places like Crawford Market and Zaveri Bazar, people were selling Rs 1,000 notes for as little as Rs 300,“ he said.

At banks, people were asked to fill in a form when they came to exchange old notes.The banks would inform the I-T cell if people walked in with unusually large amounts. “If they were unable to explain the source of income, the I-T wing would levy the prevalent tax, which was as high as 90% in those days,“ he added.

Said advocate Nishith Desai, “I remember 1978, when people had to go with bags full of cash to the bank. It is an excellent step, but the idea is old.“

A senior chartered accountant with Kalyaniwala & Mistry said, “If you want to flush out black money , it is a good step. In 1978 there was no great disruption, however, since the notes were not with common people. Then they had demonetised Rs 1,000 notes which had a huge monetary value. The 500 and 1,000 rupee notes do not have the same value today; even the average man on the street will have these notes.“

RBI’s history (summary)

In 1978, the Janata Party coalition government, which had come to power a year earlier, decided to withdraw Rs1,000, Rs5,000 and Rs10,000 notes by issuing an ordinance on the morning of 16 January that year.

The Reserve Bank of India’s (RBI) history (third volume) describes the process in detail. It goes something like this:

On the morning of 14 January 1978, R. Janaki Raman, a senior official from chief accountant’s office in RBI, was asked by a government official over telephone to go to Delhi to discuss matters relating to exchange control.

On reaching the capital, Raman was told that the government had decided to withdraw high-denomination notes and asked to draft the necessary ordinance within a day.

During that period, no communication was allowed with RBI’s central office in Mumbai, “since such contacts could give rise to speculation.”

The draft ordinance was completed on schedule and sent for signature to President N. Sanjiva Reddy in the early hours of 16 January. The news was announced on the All India Radio news bulletin at 9 am on the same day. The ordinance provided that all banks and treasuries would be closed on 17 January.

The then RBI governor I.G. Patel was not in favour of this exercise. According to him, some people in the Janata coalition government saw demonetization as a measure specifically targeted against the allegedly “corrupt predecessor government or government leaders”.

Patel recalled in his book Glimpses of Indian Economic Policy: an Insider’s View, that when finance minister H.M. Patel informed him about the decision to withdraw high-denomination notes, he had pointed out that such exercises seldom produces striking results.

Most people, Patel said, who accept illegal gratification or are otherwise recipients of black money, rarely keep their ill-gotten earnings in the form of currency for long.

The idea that black money or wealth is held in the form of notes tucked away in suitcases or pillow cases is naive, Patel said. In any case even those who are caught napping or waiting will have a chance to convert notes through paid agents as some provision has to be made to convert at par notes tendered in small amounts for which explanation cannot be reasonably sought, he added.

Excerpts from The Reserve Bank of India’s official history

The following is the entire relevant chapter from RBI's official history

DEMONETIZATION OF HIGH DENOMINATION NOTES

Demonetization of high denomination notes is one of the radical measures normally resorted to by governments to counter forgery and illegal printing of notes by unauthorized sources. The Wanchoo Committee on Black Money had recommended demonetization many years ago. This suggestion was not acted upon, partly because the very publicity given to the recommendation resulted in black money operators getting rid of high currency notes. The Committee had observed that black money should be regarded largely as a flow, not as a hoard, and different members of the Committee held different views on how much black money was in circulation.

The Times of India

The government resorted to demonetization of Rs 1,000, Rs 5,000 and Rs 10,000 notes on 16 January 1978 under the High Denomination Bank Notes (Demonetization) Ordinance, 1978 (No. 1 of 1978). The Finance Minister, in his budget speech of 28 February 1978, announced that demonetization was part of a series of measures that the government had taken for controlling illegal transactions and against anti-social elements. The purpose of the Demonetization Ordinance was stated in the preamble thus:

<<The availability of high denomination bank notes facilitates the illicit transfer of money for financing transactions which are harmful to the national economy or which are for illegal purposes and it is therefore necessary in the public interest to demonetize high denomination notes.>>

According to the Ordinance, all high denomination bank notes ceased to be legal tender in payment or on account at any place after 16 January 1978. The Ordinance further prohibited the transfer and receipt of these notes between persons after 16 January 1978 so as to make itself operationally meaningful.

The demonetization of 1978 was the second such exercise in India, the first one having been conducted in 1946. Governor I.G. Patel was not in favor of this exercise. According to him, some people in the Janata coalition in the government saw demonetization as a measure specifically targeted against the allegedly ‘corrupt’ predecessor governments or government leaders. Patel recalled in his book, Glimpses of Indian Economic Policy: An Insider’s View, that when Finance Minister H.M. Patel informed him about the decision to demonetize high denomination notes, he had pointed out that:

such an exercise seldom produces striking results. Most people who accept illegal gratification or are otherwise the recipients of black money do not keep their ill-gotten earnings in the form of currency for long. The idea that black money or wealth is held in the form of notes tucked away in suit cases or pillow cases is naïve. And in any case, even those who are caught napping—or waiting—will have the chance to convert the notes through paid agents as some provision has to be made to convert at par notes tendered in small amounts for which explanations cannot be reasonably sought. But the gesture had to be made, and produced much work and little gain. (p. 159) Demonetization was a sensitive issue and secrecy was imperative. R. Janakiraman, a senior official in the chief accountant’s office in the Reserve Bank, was asked by some officers of Government of India over the telephone on 14 January 1978, to go over to Delhi immediately on ‘some urgent work’. When he enquired the purpose of the visit so that he could go prepared, the officials stated that matters relating to exchange control would need to be discussed and that he should leave for Delhi on his own.

Janakiraman, however, took along with him M. Subramaniam, a senior official of the Exchange Control Department. On reaching Delhi, it was revealed that the government had decided to demonetize high denomination notes and he was required to draft the necessary Ordinance within twenty-four hours. During this period, no communication was allowed with the Bank’s central office in Bombay, since such contacts could give rise to speculation. Janakiraman and Subramaniam made a request for the 1946 Ordinance on demonetization to get an idea of how it was drafted, and the request was acceded to by the Finance Ministry. The draft Ordinance was completed on schedule; it was then finalized and sent for the signature of the President of India (N. Sanjiva Reddy) in the early hours of 16 January 1978. The news was to be announced on All India Radio’s news bulletin at 9 am the same day; it was given as a flash towards the end of the news bulletin.

The Ordinance provided that all banks and government treasuries would be closed on 17 January 1978 for transaction of ‘all business except the preparation and presentation or the receipt of returns’ that were needed to be completed in the context of demonetization. For purposes of the Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881, 17 January 1978 was deemed to be a public holiday notified under the Act.

Issuing the Ordinance was one matter. Implementing it and working out the modalities to receive and exchange notes across the length and breadth of the country was another. The Ordinance contained comprehensive provisions for the exchange of notes held by banks and government treasuries as well as by the public; for exchange of notes after the time limit; and provisions related to offences and the power of the central government to make rules giving effect to the provisions of the ordinance.

Banks and government treasuries were required to submit information (in the form of data ‘return’) to the Reserve Bank of high denomination notes held with them as at the close of business on 16 January 1978. The notes held would be exchanged for an equivalent value by the Bank. The general public2 was given three days to surrender high denomination notes for conversion. After 16 January, notes could be exchanged on tender of the high denomination notes in person by the individuals themselves or by a person competent to act on his/her behalf. They had to tender the notes at the Reserve Bank or at notified banks in the prescribed format with full particulars giving, among other things, the source or sources from which the notes came into his/her possession and the reasons for keeping the amount in cash.

( The term public included the Hindu undivided family (HUF) where the karta was required to tender the notes, companies where directors where required to tender the notes, firms (managing partner), associations (principal officer), etc.)

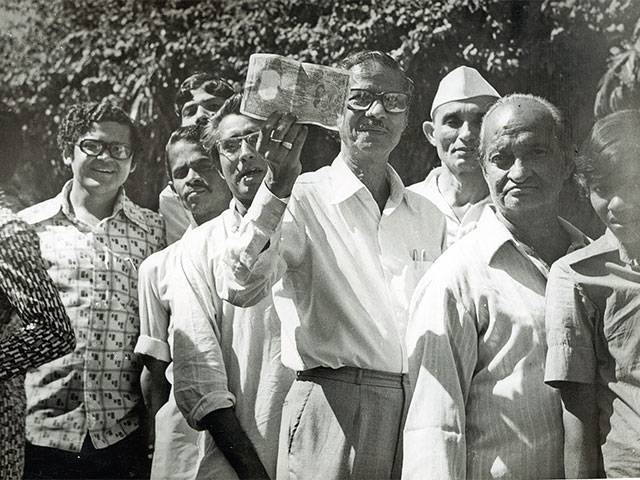

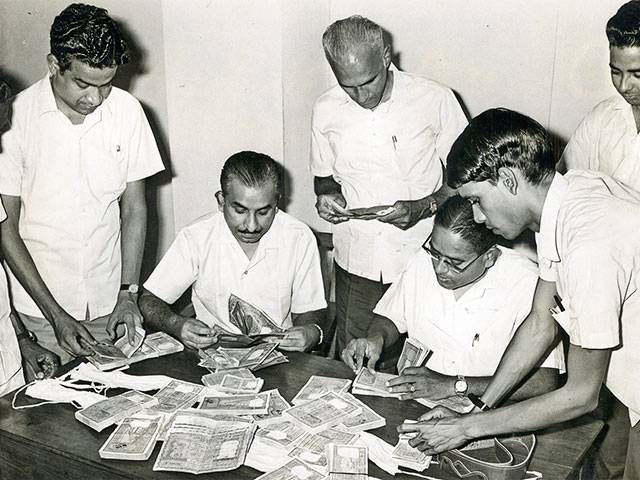

The arrangements for exchange of high denomination notes to be surrendered by the public at the Reserve Bank in Bombay required that the Bank open additional counters and mobilize manpower from other departments to meet the high demand. Long winding queues started forming in front of the Reserve Bank office right from the morning as also at the main office of the State Bank of India, to collect declaration forms. According to press reports on 18 January 1978, the day started with utter confusion over the issue of declaration forms at the Reserve Bank headquarters at Bombay and the working hours stretched to 6.30 pm. Enterprising city printers are said to have made quick money selling forms in sets of three for Rs 3. As expected, there were frayed tempers and a considerable hue and cry from the public as well as foreign tourists, especially those who did not have, or did not care to preserve, documentary proof to support the exchange of notes. Many tourists were reluctant to fill the forms, particularly tourists from the Gulf countries. Generally tourists who had a small number of currency notes of high denomination had their notes exchanged across the counter.

On the day following demonetization, two noted economists, Professor C.N. Vakil and Dr P.R. Brahmananda, expressed the view that the measure would not have any enduring effect on money supply, prices of necessities and problems like low savings, acute poverty, unemployment and industrial relations, as the high denomination currency notes formed only a small proportion of the total money supply. They were the authors of the memorandum titled ‘Semibombla’ submitted to the union government for tackling the inflationary situation in 1974.

The impact of the 1946, 1978 demonetisations

Failure

The past experiments with demonetisation had ended in failure, as a 2012 report by a black money committee headed by the chairman of Central Board of Direct Taxes (CBDT) noted.

The report titled, 'Measure to tackle Black Money in India and Abroad', while discussing demonetisation as one of the ways to 'kill' the black economy or curb generation of black money, found it impractical despite its 'noble aims'. It revealed that in both instances of demonetisation, in 1946 and 1978, less than 15% of high currency notes were exchanged, while over 85% of the currency notes never surfaced, as the owners feared penal action by central agencies.

The report quoted former Delhi University professor and economist Suraj B Gupta who criticised the measures taken by the government to unearth black money. In his study, 'Black Income in India' (1992), Gupta discussed the Voluntary disclosure of Income (VDI) Schemes of 1951, 1965, 1975 and 1985, Special Bearer Bond (SBB) Scheme of 1981, and the demonetisation of currency in 1946 and 1978, apart from touching upon the schemes launched by the government in 1991-92.

His critique mostly indicated that tackling the black money menace had to do with implementation of existing laws and prevention measures. Thanks to improper execution of statutory tax provisions; ineffective surveys, search and seizures; enforcement of few penalties; and rare prosecutions due to legal loopholes, the black money economy thrived.

The report also quoted former JNU professor Arun Kumar who in his study, 'The Black Economy in India' (1999) wrote against the 1978 demonetisation. Kumar, in fact, had also termed the voluntary disclosure schemes and lowering of tax rates as failures.

The report mentioned that demonetisation of Rs 1,000 and Rs 500 was one of the crucial demands from the public, but observed that it may not be a viable solution when it comes to tackling black money as unaccounted money is largely held in the form of benami properties, bullion and jewellery, and not as wads of currency notes.

The report also noted that demonetisation would only increase the cost associated with currency note production, as more currency notes would have to be printed for disbursing the same amount of money.

Reactions of the public to possible demonetisation were adverse, according to the report. They said the move was likely to have an adverse impact on the banking system with its logistics becoming difficult, and would leave the general public inconvenienced as payments of wages/salaries to workers would become challenging.

1978: The transition to new notes was less painful

Ohe morning of Tuesday, January 17, news reports screamed “High Currency Demonetised”.

There was absolutely no hint then of what was coming — with the only national news pointer from him that weekend being that he would never encourage or rule through “an Emergency”, according to the lead story in Sunday Standard — the Sunday edition of The Indian Express.

ON SATURDAY, January 14, 1978 — two days before the Janata government announced its decision to demonetise or scrap Rs 1,000, Rs 5,000 and Rs 10,000 notes — Prime Minister Morarji Desai was in Bombay, garlanding the statue of Shiva ji and addressing a massive rally of 1,00,000 people at Shiva ji Park, as he enjoyed a historic reception by the Bombay Municipal Corporation.

Before he called for a “halt to the strident demands of organised sections of the country for larger portions of the economic cake,” Morarji Bhai did pause to speak of the city’s “sprouting skyscrapers which disfigured the skylines,” going on to add that he “did not think this was progress”.

Of course, the man who was chief minister of Bombay State was also amused, knowing “Bombay did not get filtered water,” admiring the tolerant nature of those living in the city and commending their spirit of “bear it till things improve.”

There was absolutely no hint then of what was coming — with the only national news pointer from him that weekend being that he would never encourage or rule through “an Emergency”, according to the lead story in Sunday Standard — the Sunday edition of The Indian Express.

These were the early days of the Shah Commission, which was probing the excesses committed during the Emergency under former Prime Minister Indira Gandhi — with the front page always filled with submissions made by witnesses. On Sunday, in the run up to the demonetisation of 1978, Moraji Desai was seen at Bhavnagar spending 45 minutes of his public address offering to resign if anyone could prove allegations that his son Kantibhai Desai embezzled party funds.

All this was quickly drowned out on the morning of Tuesday, January 17, with news reports screaming “High Currency Demonetised”. The Government soon made two announcements — indicating that it had detected a “high level of smuggling transactions” and also openly calling out “political money from previous governments” as the trigger for the announcement.

Powai resident Rekha Vijaykar, now 75, recalls those days, saying “oil was still Rs 6 per litre.” She speaks of a different era — one marked by the “common man’s sensitivity.” According to her, the middle class and lower middle class were not affected at all considering the notes were all high value. “There was a general apprehension but it settled down with time,” she says.

The government justified the demonetisation move, saying that the high-value notes were believed to facilitate illicit transactions that were “harmful to the national economy.” President Sanjiva Reddy, a report in The Indian Express reads, promulgated an ordinance after an emergency Cabinet meeting held in utmost secrecy, withdrawing high-value currency notes from circulation.

A bank holiday was declared for the next day, to enable “them to prepare and present to the Reserve Bank of India tomorrow by 3 pm returns showing the total value of high denominational notes held by them at the close of business on January 16.

Only RBI, SBI and 71 offices of public sector banks existed then, which accepted currency notes for exchange. People were asked to declare the source, time and manner of acquisition of the high denomination notes. Persons making false declarations were liable for a term extending to three years with a fine or both.

The move saw a similar rush as on Tuesday last week with many impacted, a few even calling in sick and sporadic reports of people fainting in lines, and even two cases of heart attacks.

The decision took many by surprise as city newspapers had earlier reported that the Finance Minister in a public meeting had confirmed no such proposal was in consideration, after reports emerged that the newly formed Janata government would heed the Direct Taxes Enquiry Committee (Wanchoo Committee)’s confidential report in 1970-71. The confusion that followed was expected, with stories of smugglers scrambling.

In Mumbai, with just six branches of public sector banks open, the crowd lined outside the RBI for three days. The forms required for exchanging the notes were also in short supply, worsening the chaos as the deadline loomed close.

There are anecdotes of a few Arab nationals who reached the RBI office at Ballard Estate with “bundles of Rs 1,000” notes, demanding immediate change as they had to leave the country. They kept yelling about the counter of a posh hotel in south Bombay where they stayed as the source of the money. Except that when the RBI officials called to check, the hotel denied any knowledge.

In temple dhanpatis across the city donations surged and at least in two temples the money which poured in broke all past records. By evening of the first day of scrapping these notes the RBI governor (I G Patel) called to all priests, asking them to adhere to the Thursday deadline, quipping that the order applied as much to “gods as to men”.

According to reports, the unofficial rate at which people in Bombay were selling excess Rs 1,000 notes was as low as Rs 250. Trading in bullion — as was seen this week— didn’t take place then, with the rate for gold frozen at Rs 693.

It came to be known that Rs 1,000 notes were being held by commercial and co-operative banks. The RBI in its bulletin soon indicated that the three denominations together made up about Rs 150 crore, with Rs 1,000 notes numbering the highest.

Dr Avinash Supe, now the dean at KEM hospital, was a medical student in the 1970s, living on pocket money of Rs 30 per week. “The government hospitals faced no issue back then. Larger denomination notes were not there. Since treatment cost was also low people had no trouble in getting treatment done.”

The current demonetisation move has left patients scrambling to pay hospital dues, with several getting turned away for having notes of Rs 500 and Rs 1,000. “Back then, the transition was smooth,” Supe recalls.

In the city, the RBI exchanged the Rs 1,000 bill of a lone patient who had no one in the city and was admitted for a serious ailment. By the Thursday deadline, the RBI’s Bombay branch had received an account tally of 6,628 pieces of high denomination notes to the value of Rs 66.61 lakh.

In Bombay, late on Thursday evening, the RBI Governor made a public appearance saying “whoever was found inside the bank hall would be serviced fully but whoever happened in the queue outside would be given a token.”

This was to be shown till January 24, the last day for exchange. By then a total of 200 bank employees worked in Bombay at 53 counters daily.

Why 1978 demonetisation didn’t hurt India

Quite simply, it involved only 1.8% of the currency notes in circulation then

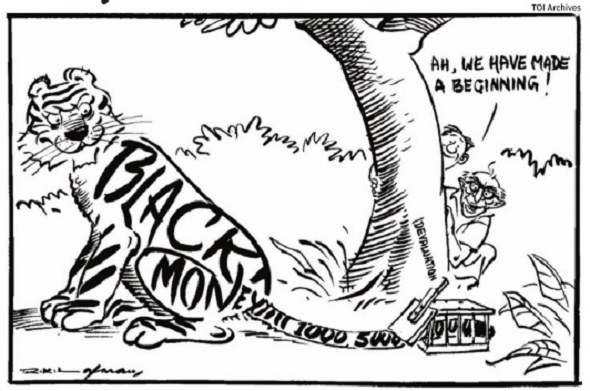

This graphic published in The Times of India on November 16, 2016 conveys the panic that must have gripped India after currency notes of Rs 1,000, Rs 5,000 and Rs 10,000 were demonetised on Monday, January 16, 1978. Comparisons with the prevailing cash crisis are natural. But did India really panic 38 years ago? No, and here’s why:

Surgical Strike

Prime Minister Narendra Modi has likened his November 8 decision to demonetise Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 notes to a military ‘surgical strike’, but others say it resembles ‘carpet bombing’ because every citizen is affected by it. In contrast, the 1978 demonetisation was genuinely a surgical manoeuvre as only the truly high-denomination notes were taken out.

Indpaedia adds: In 1978 the starting salary of an Army or IAS officer was Rs1100 and in top private firms like the Tata Adminsitrative Service or Hindustan Lever around Rs.1400. in those days the currency note used most even by well to do people was not Rs.100 but Rs.10 (equal to around Rs.450 in 2016).

A Rs 1,000 note from 1978 would be worth Rs 13,689 today. Conversely, the just-demonetised Rs 1,000 note would have been worth only Rs 73 back then.

There were demands in and before 1978 to demonetise even the Rs 100 note — worth Rs 1,369 now— but neither the Janata government of 1978, nor the Congress governments before it, heeded them. Most salaried people earned less than Rs 1,000 a month and the pain would have been felt all across.

Unlike now, when 86% of India’s currency has been frozen, the 1978 demonetization affected a minuscule proportion of currency notes. Although they were the highest denomination notes, together they amounted to only about 1.8% of the currency in circulation, by value.

So, why are hundreds of people in the queue outside Reserve Bank of India’s Mumbai building in the January 18, 1978 photograph used above?

Only 3 Days To Deposit

Although the general public was not affected by the demonetisation, a rush ensued at Reserve Bank and State Bank offices because the government gave only three days to deposit the high-denomination notes.

The owners of large notes had to visit “the office or sub-office or branch of the Reserve Bank of India or the main office or branch of the State Bank at the headquarters of a district or any other office of a public sector bank notified in this behalf by the Reserve Bank” in person, and submit their notes along with a declaration by Thursday, January 19, 1978.

If they failed to exchange the notes within those three days, they had to submit the notes and the declaration at an RBI office by January 24, along with an explanation for the delay. General banking operations were not affected by the decision and the chaos, if any, was over within a week.

Why Demonetise?

Why were high-denomination notes demonestised in 1978? Surprisingly, then minister of finance, revenue and banking H M Patel told Parliament on March 23, 1978, the government had NOT targeted black money:

“The total number of these notes in circulation was worth Rs 145 crore (1.45 billion). The total number of notes in circulation in this country today is over Rs 8,000 crore (80 billion). Therefore, quite obviously this could not have ever been designed to achieve anything of the nature of trying to attack even the black money problem, etc. It had no such objective…The objective was one of preventing illegal transactions and that will certainly be achieved…”

During the debate before the passage of the High Denomination Bank Notes (Demonetisation) Bill, 1978, Patel said:

“It was brought to Government’s notice that high-denomination banknotes were being used extensively for illicit transfer of money for financing transactions which are harmful to the national economy or which are for illegal purposes. Immediate action to demonetise banknotes of the denominational value of Rs 1,000, Rs 5,000 and Rs 10,000 issued by the Reserve Bank of India was, therefore, considered necessary by Government in public interest.”

Politically Motivated?

The government had ordered demonetisation through an ordinance shortly before Assembly elections in some states. The Opposition then, as now, cried foul and alleged the decision was politically motivated.

Noorjehan Razack, an AIADMK member of Parliament from Tamil Nadu, said: “The timing of this demonetisation ordinance was such that it appeared more as a political act on the eve of the Assembly elections to take the teeth out of certain political parties than a purposeful, well-directed and well-coordinated economic offensive against the well-entrenched forces of black money.”

Sanat Kumar Raha, a CPI member of Parliament from West Bengal, said: “This ordinance was promulgated just before the elections and it has already strengthened the doubts and suspicions in the minds of the people… When the government brought out the ordinance it was nothing but a case of publicity, and not a matter of performance. The publicity was meant only as a political stunt because the government wanted to give some radical ideas.”

Little To Show In The End

What did the 1978 demonetisation achieve? It certainly did not root out corruption or black money, or the whole country wouldn’t be going through the trauma of another, bigger sweep-up 38 years later. By the end of the action, high net worth individuals had submitted notes worth Rs 595.5 million while Rs 649.5 million in large notes was found to be in the possession of banks. About Rs 160 million remained unaccounted.

On April 25, 1978, minister of state for finance Zulfiquarullah told Parliament: “Notes of an approximate value of Rs 16 crore (160 million) have not been tendered. They have ceased to be legal tender and are therefore valueless. No follow-up action is necessary.”

Six months after demonetisation, Patel summed up the results thus on July 18, 1978:

“The demonetisation of high-denomination notes had the limited objective of stopping the illicit transfer of money for financing transactions, which, apart from resulting in tax evasion, were harmful for a healthy growth of the economy. The measure resulted in the high-denomination banknotes of an approximate value of Rs 16 crore (160 million) not having been tendered for exchange becoming valueless and therefore, would not form part of money supply. Apart from the psychological impact which such a measure has had on tax evaders, black-marketeers etc, it has yielded valuable information to tax authorities in respect of persons who tendered high-denomination notes for exchange, which, it would appear, indicates tax evasion in a number of cases.”

It merely told government where to sniff next time. But that information couldn’t have been a secret anyway.

1946 and 1978: Stories from the past

The media in terms of numbers was limited in 1946 and 1978 when compared to 2016. But given the importance of the decisions, it did trigger coverage.

Newspaper and magazine archives of the 1946 decision do not seem to be available online. Therefore, I relied on Reserve Bank of India commissioned history of India’s central bank to get an idea of how a stakeholder perceived the decision.

The following extract of RBI’s history volume is sourced from “Mostly Economics,” a blog on economic developments in India.

According to RBI’s relevant volume:

“Sir Chintaman Deshmukh (governor) felt that we may not get even as much as Rs. 10 crores as additional tax revenue from tax evasion and that the contemplated measure, if designed to achieve such a purpose, has no precedent or parallel anywhere. If value is going to be paid

for value (no matter whether such value is in lower denomination notes), it is not going to obliterate black markets. His advice is that we should think very seriously if for the object in view (as he deduces from the declaration form) whether this is an opportune time to proceed

with the scheme. Provided Government are satisfied on the points of (i) sparing harassment to the unoffending holders and (ii) a worthwhile minimum of results in the shape of extra tax revenue, he does not wish to object to the scheme as drafted, if Government wish to proceed with it notwithstanding the administrative difficulties involved.”

It was not the first time an RBI governor was skeptical of government’s move to strip currency of legal tender characteristic at short notice.

In 1978, when Janata government proclaimed an ordinance, some of the media coverage of the development was available online.

A Times of India report (sourced in-house) published on 17th January 1978 said:

“A press note issued tonight said that the ordinance had been promulgated because there was reason to think that high-denomination notes were facilitating the illegal transfer of money for financing transactions which are harmful to the national economy or which are for illegal purposes. There has been concern in recent months over the behaviour of agricultural prices particularly of edible oils. In spite of a bumper harvest agricultural prices are ruling much higher than after the poor harvest of 1976- 77. Massive imports of edible oil have failed to bring down prices and the mustard oil price control order has failed miserably to give the consumer his requirements at the specified rate. There has been a feeling that a considerable amount of black money has gone to finance hoarding and speculation. The demonetisation of high denomination currency notes will hit black money hard.”

An analysis of the move was written by Jay Dubashi in one of India Today’s February editions. Dubashi reported that the ordinance had a ripple effect on other markets such as gold and diamond where prices slumped by 5 to 10% within a week. In addition, the old notes were going at 70% discount in Bombay’s Zaveri Bazar.

In his report, Dubashi wrote:

“Politics apart, the demonetization is unlikely to curb black money in circulation, for the simple reason that no one really knows how much black money there is in circulation and, even more important, whether black money can really be defined in precise terms in all its shades.”

I.G Patel was governor of RBI when the ordinance was promulgated in 1978. He was not happy about the government move.

“Mostly Economics” quotes the relevant part from Patel’s memoirs which are as follows.

“such an exercise seldom produces striking results. Most people who accept illegal gratification or are otherwise the recipients of black money do not keep their ill-gotten earnings in the form of currency for long. The idea that black money or wealth is held in the form of notes tucked away in suit cases or pillow cases is naïve. And in any case, even those who are caught napping—or waiting—will have the chance to convert the notes through paid agents as some provision has to be made to convert at par notes tendered in small amounts for which explanations cannot be reasonably sought. But the gesture had to be made, and produced much work and little gain.”

1978 demonetisation law not unreasonable, SC

Mumbai: The last time the Centre demonetized high denomination notes, nearly four decades ago, it also resulted in a challenge to its validity. A challenge the Supreme Court dismissed two decades ago as being "wholly misconceived".

The High Denomination Bank Notes (Demonetisation) Act, which replaced an ordinance, was brought into effect early 1978. Its validity was assailed in 1979, on grounds that it impinged on the fundamental right to trade and as it stood then, to property. In 1996, a five-judge Constitution bench of the SC upheld it as a valid legislation. "It can't be said it was not enacted for public purpose," a bench of Justices Kuldip Singh, M M Punchhi, N P Singh, M K Mukherjee and S S Ahmad had said. There was no dissenting judgement.

"From the preamble it was manifest that the Act was passed to avoid the grave menace of unaccounted money, which had resulted not only in affecting seriously the economy of the country but had also deprived the state exchequer of vast amounts of its revenue," said the ruling authored by Justice Mukherjee.

The objective in the gazetted notification to scrap Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 notes from November 9 is similar.

The SC had rejected a challenge of unreasonableness to the limited seven-day deadline then, for exchange of old high denomination notes—defined as those with a value of Rs 1,000, 5,000 and 10,000, that had been rendered illegal tender from January 16, 1978.

The SC referred to the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) Act of 1934 which empowers the RBI to issue bank notes and imposes an obligation on it to exchange those notes, as legal tender. Section 26 of the Act allows the Centre to notify any series of bank notes to cease to be legal tender. The arguments centred around provisions for exchange of notes, as refusal by banks violated their fundamental and legal rights, the petitioners J R Shah and others claimed. People had to submit their cash by January 19 or latest by January 24. But the SC held, "after compulsory acquisition under the Act, their "rights thereto stood extinguished. "Equally untenable is the contention that they were deprived of right to compensation for such acquisition since the Act laid down "elaborate procedure to apply and obtain equal value of the notes held.

Any extension of time to tender money to banks for exchange would "defeat the very purpose of the Act of banning circulation and transfer of the notes.

Senior advocate Rajiv Kumar in Mumbai said, "Demonetisation is a valid law but it needs to be brought in as a financial policy every five yearly basis. That would deter a parallel economy and more significantly reduce hardships to the common man, caught up in a move targeted at hoarders.

Unlike in 1978, the scrapped notes are available even with the masses. The RBI pegs Rs 500 notes in circulation at 16.5 billion and Rs 1000 notes at 6 billion. While the Centre has assured a review after 15 days on the exchange of currency, solicitor Ashok Paranjpe said, "in view of the huge quantum, it would be helpful if time is extended to avoid the huge inconvenience being caused to general public.

1946 and 2016: Stories from the past

Manimugdha Sharma, 2016 vs 1946: Tale of two notebandis, Dec 11 2016 : The Times of India

From long queues to heart attacks, the two demonetisations have a lot in common

On November 7, a young man in Kanpur received Rs 70 lakh in Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 notes as advance for a plot of land he was selling. On November 8, as Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced demonetisation, the man had a cardiac arrest and died.

Seventy years ago, on January 12, 1946, a 40-year-old woman died of heart failure in Karachi, then a commercial hub of British India. She had saved up Rs 10 lakh in 1,000-rupee notes, rendered invalid by the Government of India's High Denomination Bank Notes (Demonetisation) Ordinance, according to a Times of India report on January 14, 1946.

For a few weeks after that move, there were several reports in the Indian press on never-ending queues outside banks, on how the Raj move against `black capitalists' was bound to fail as they would invest in gold bullion and real estate, and how Britain and Australia had done it without causing much hardship to their citizens.

The similarities between the two demonetisation exercises and the impact they had on people's lives are striking. Indeed, if you were to read TOI's coverage during the period, you might wonder if it's talking about 1946 or 2016.

MAKING NEWS

In the edition dated January 19, 1946, TOI said “there was a Gilbertian wit and wisdom“ behind the move, while arguing the costs and benefits of it. Our editorial dated January 25, 1946, took a balanced view: “The main grounds of criticism are that the step was taken after much black market money had already found refuge in gold, securities, jewellery, and land...It is felt that by splitting up their holdings, some of the largest note hoarders may escape without a trace. There is an element of truth in that criticism.“

In Bombay alone, it was estimated that 80,000 people had their savings in Rs 1,000 notes. The number was far greater for those having Rs 500 notes.But unlike now, the move wasn't projected as a great masterstroke to end “black capitalism“. “It has never been claimed that demonetisation was a specific cure for the black markets...big notes and black markets go together,“ the TOI editorial had said then. Several letters to the editor showed that people were quite happy that the illgotten wealth of the rich would be rendered useless. The Congress had criticised the move even then. Dr Rajendra Prasad spoke to the press on behalf of the Congress Working Committee. “I do not know how far and to what extent the new ordinance will be able to affect the persons for whom it is intended. One thing is clear. A large number of people belonging to the middle and lower middle classes will be hit hard on account of the demonetisation of currency notes of the value of Rs 500 and Rs 1,000,“ Prasad said (TOI, January 16, 1946).

He added, “While we, Congressmen, have no sympathy for profiteers and dealers in the black market, it is not right to penalise honest people who in good faith have their savings in notes of demonetised value.“

As it turned out, this big-bang move to curb the shadow economy didn't quite succeed. Black-marketeering thrived in the run-up to Partition and Independence.

TWIN DEMONS

Incidentally, demonetisation in 1946 came close on the heels of large-scale demobilisation of the armed forces. Post World War II, growth slumped, jobs became scarce and there was a food crisis. Between 1939 and 1945, the colonial state had recruited over 2.5 million people for war service. These men had to be released from military service after the war, adding to the swelling ranks of the unemployed. Military historian and Delhi University professor Anirudh Deshpande has narrated how the Raj bungled up the demobilisation exercise in his book, Hope and Despair: Mutiny , Rebellion and Death in India, 1946.

According to Deshpande, demobilisation in the Royal Indian Navy, in particular, was shoddily done. In February 1946, a little over a month after the demonetisation exercise, the navy rose in revolt. Soon, trade union and peasant revolts broke out in the country.The British used brute force to crush the rebellion.

See Royal Indian Navy (RIN): 1946 uprising

Demonetisation added to the post-war economic distress of the people. The political instability that followed tore their lives apart. In the summer of 1946, the country was gripped by horrifying communal riots. And the road to Independence became a slippery slope that hurtled India towards Partition.

Debate on demonetisation between 1978 and 2015

Economic Times had recommended demonetisation before it actually took place in 2016. See below.

Against: Finance ministry committee, 2012

A high-level finance ministry committee, set up to suggest measures to track black money in the country and abroad, had in its report in 2012 opposed demonetisation of Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 notes and said it was not a solution to trace illicit wealth which was largely held in the form of benami property , bullion and jewellery . The previous two attempts at demonetisation only had partial success with just 15% of high currency notes coming back into the system, the panel had said.

The committee, which was headed by chairman of the Central Board of Direct Taxes and had director general (DG), currencies, as its member, had observed that such measures would only have an adverse impact on the banking system.

“Demonetisation undertaken twice in the past (1946 and 1978) miserably failed, with less than 15% of high currency notes being exchanged, while more than 85% of currency notes never surfaced as the owners suspected penal action by government agencies,“ the report had said. The committee was constituted in view of civil society unrest in 2011 and against the backdrop of a series of CAG reports on “loss to the exchequer“ on account of government policies benefitting corporate houses.

The DG, currencies, pointed to the huge economic cost of demonetising higher denomination notes and observed that “it was not a feasible idea“.

“Further, demonetisation will only increase the cost, as more currency notes may have to be printed for disbursing the same amount. It may also have an adverse impact on the banking system, mainly logistic issues,“ the report had said. The panel had also said that huge amounts of black money was invested in real estate and it was difficult to detect this.

For: ET/ Nathan: ‘Withdraw Rs 500/ 1,000 notes’ / May 2016

This article had asked the government to withdraw Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 currency notes six months before the actual demonetisation.

Increased currency in circulation is a burning issue we are facing now. As on April 29, 2016, total value of currency in circulation has reached Rs 16.50 lakh crore, an increase of 15.32% compared to same period last year. This 15% plus yoy growth is happening continuously for the last 2 months now, something not seen after July 2011.

There are several theories explaining this spike. The first theory states that it is because of the just completed assembly elections in five states. But a close look at currency in circulation data will reveal that the increase is more gradual and therefore, these elections are not the main reason behind this spike. More importantly, there were bigger elections earlier and the currency circulation was smaller then. For example, currency in circulation now is 27.55% more than 2 years back, when national election was going on.

Increased banking restriction may be another reason for this. For example, you need to furnish PAN details now for depositing more than Rs 50,000 in cash. Due to this, black money stays outside the banking system. Co-operative banks used to be a safe haven for tax evasion because they were exempt from deducting TDS on deposit by members. Now they have to deduct TDS for everyone, including its members.

Since black money can’t be used for buying financial assets, the same is used for purchasing mostly real estate and gold. The cash component is still very high in real estate transactions. The government’s efforts to tackle gold import by imposing 10% import duty compounded the problems further. Though official gold import figures have come down, a large part of that shifted to smuggled route. Foreign payment for smuggled gold can’t happen through official banking channel and has to be either smuggled cash or through some other stuffs smuggled outside. Similarly, from smuggling point to the end consumer, transactions have to happen in cash.

Situation has come to such level that this has started hurting bank’s deposit growth. So what should the government do? No need to dilute anti-money laundering measures because they are in right directions. Reducing gold import duty is one solution as it will reduce gold smuggling and resultant need for cash transactions.

Since more than 80% of money in circulation are through Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 notes, the best solution to this problem is the withdrawal of these notes from circulation. How will it benefit? First, withdrawal of Rs 500 and Rs 1000 rupee notes will result in immediate unearthing of black money. This is because people who are hoarding black cash currency will be forced to come to banking system for converting.

Second, withdrawal of high denomination notes w ill help to reduce black money generation in future. This is because it will become difficult to deal in cash, especially for large deals that runs into crores. Smuggling of Indian currency outside also become really difficult. This is very important for our national security also because terror outfits usually use smuggling and black money route for financing. Major economies have already started taking steps in this direction. Only recently, the European Central Bank has decided to stop printing Euro 500 bank notes, popularly known as ‘Bin Laden notes’, because of its association with money laundering and terror financing.