Farmers, cultivators and their issues: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. the Facebook community, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be acknowledged in your name. |

Backgrounder

The number of farmers/ dependence on agricultural income: 2004-19

Nov 21, 2021: The Times of India

From: Nov 21, 2021: The Times of India

From: Nov 21, 2021: The Times of India

From: Nov 21, 2021: The Times of India

From: Nov 21, 2021: The Times of India

From: Nov 21, 2021: The Times of India

From: Nov 21, 2021: The Times of India

From: Nov 21, 2021: The Times of India

Agriculture has long ceased to be a prime income generator for the Indian economy, with less than 15% of GDP coming from the sector. But it still employed more people than other sectors. A new study finds that to be no more the case with the share of youth working on farms falling below 15%

The repeal of farm laws may appear like a victory to some farmer leaders, but it’s not. By blackmailing the government—which was guilty of passing the laws without adequate outreach to farmers—into withdrawal, farmer leaders have ensured that farming remains inefficient, unrewarding, dependent on subsidies funded by the middle-class and damaging to the environment.

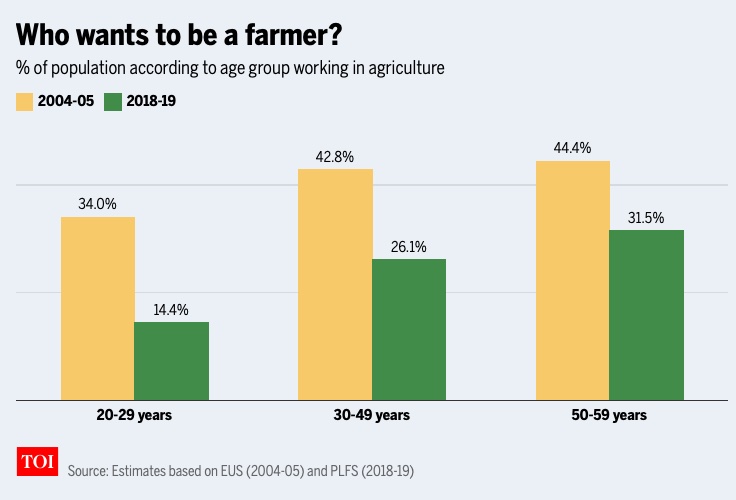

Worse, farming won’t become attractive for young Indians who have been turning away from agriculture given the mess it is trapped in for years. A recently released study shows that the share of 20-to-29 years old working in agriculture has collapsed from 34% to 14.4% in just 14 years. Here are the key details.

These numbers highlight the declining primacy of agriculture in India’s economy. Yet, about 40% of the total employment continues to be in agriculture, it is often said. At the same time, we hear about shortages of farm labour. How do the two go together? To find out the true extent of India’s dependence on agriculture and how it varies across age groups and states, a team of three researchers looked at the unit-level data of the Employment and Unemployment Survey, 2004-05, and the Periodic Labour Force Survey, 2018-19. The researchers – Vidya Mahambare of Great Lakes Institute of Management and Sowmya Dhanaraj and Sankalp Sharma of Madras School of Economics – considered only the 20-to-59-year age group, which they call prime working age segment, because while older people do work on farms, it is the people in the working-age group who are expected to move into an alternative job if the opportunity cost of working on farms rises. Here are some important findings of their report.

The missing farmers

The share of the working-age population (20-59 years) employed in agriculture has fallen to 23.3% in 2018-19 from 40% in 2004-05. Even in rural India, their share has fallen to 33.2% in 2018-19 from 53.7% in 2004-05. The decline is sharper in the share of the younger segment of the working-age population (20-29 years) who work in agriculture. Only about 14.4% of young adults were working in agriculture in 2018-19, down from 34% in 2004-05. “A decline of young people in agricultural work partly explains the incidents of the shortage of agricultural labour that are often reported,” the report says.

The decline of the share of young people in agriculture has also increased the median age of agriculture workers to 40 years in 2018-19 from 35 in 2004-05. The average age of agriculture workers was 46.7 and 43.4 years in Kerala and Tamil Nadu respectively in 2018-19, the highest among major states. “The ageing agriculture workforce would necessitate faster mechanisation of Indian agriculture going ahead, but fragmented farm sizes in India may pose a problem,” says the report.

Where are they going?

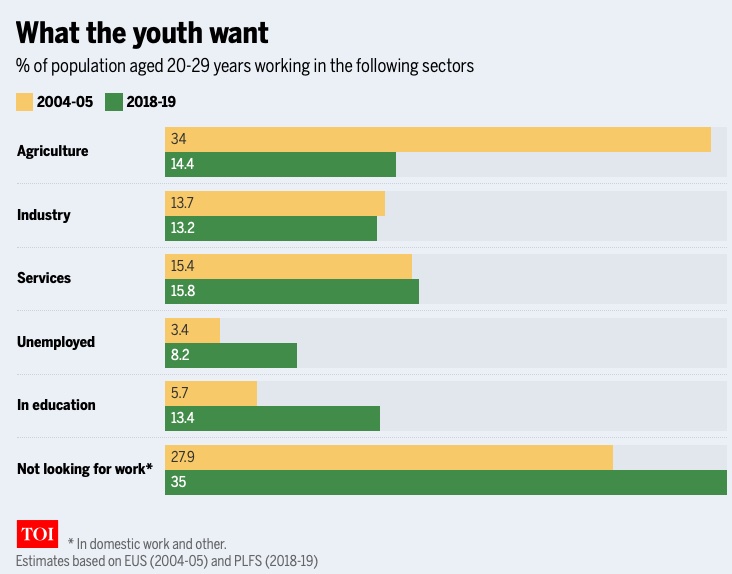

The reduction in the share of young adults in agricultural employment has been accompanied by a rise in those who report being in education (13.4% in 2018-19). However, the proportion of young adults employed in industry and services has remained stagnant. Since educated young adults would be looking to work in non-farm sectors, unemployment among them could rise if non-farm job creation isn’t fast enough, say the researchers.

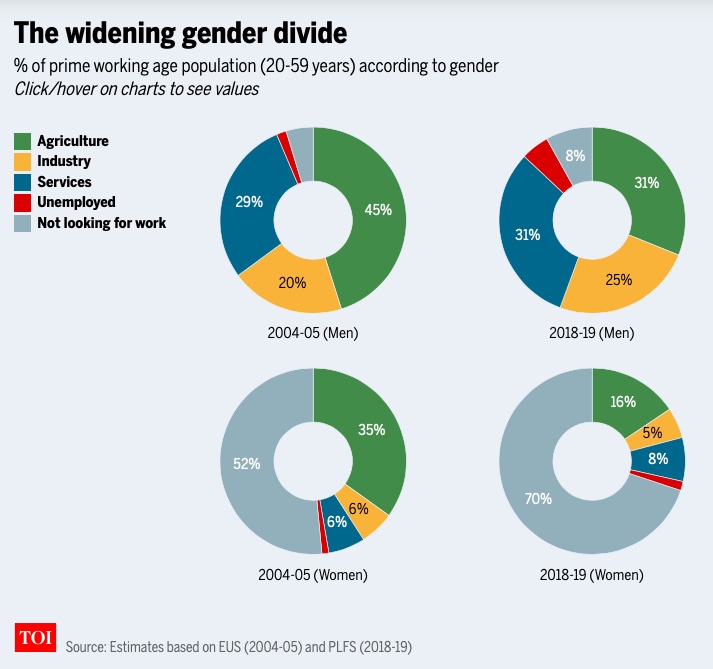

Another part of the decline in the share of the working-age population in agriculture employment can be explained with the increase in the share, mainly of women, who no longer look for paid work. The share of working-age women out of the labour force has risen to 70%. This could be because of women dropping out of work as family incomes went up.

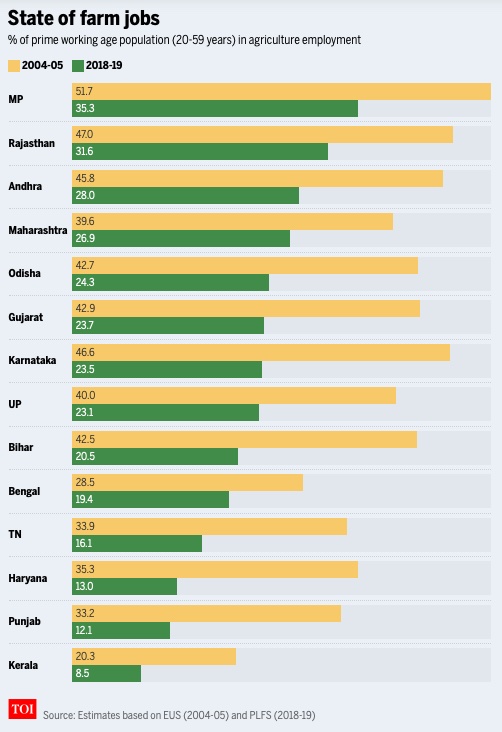

Where farms matter more

There is wide variation in the dependence on farm employment across states. While on the one end is Kerala where only 8.5% of the state’s prime working-age population was working in agriculture in 2018-19 (down from 20.3% in 2004-05), on the other is Madhya Pradesh where 35.3% of the population (down from 51.7% in 2004-05) is working on the farms. Surprisingly, even in states like Punjab and Haryana, where agriculture has a bigger share in the state economy, less than 1 in 5 prime working-age people are engaged in agriculture. This reflects higher farm productivity and incomes that allows women to exit paid farm work. On the other hand, in states like Karnataka, Maharashtra and Gujarat, 40-45% of the rural working age population was still employed in agriculture in 2018-19, pointing towards a lack of enough non-farm jobs.

Good news or bad?

That India has too many farmers working on its too small farms has been reported. That we can do with fewer farmers and more efficient farming is also known. In that sense the decline in the farm employment in of working age population doesn’t seem to be alarming. Fewer farm hands may force Indian farms to become more mechanised and improve their yields too. The decline in agriculture employment also fits in with the country’s structural transformation towards an industry and services-driven economy.

However, as the youth get educated and have higher ambitions or move out of farming because their land holdings have dwindled down to unviable sizes, they need to find suitable non-farm jobs. That is not exactly the case in India. The decline in farm employment is mirrored more in the share of the working-age population leaving the market than its share in taking up non-farm jobs.

The success in raising non-agriculture employment varies widely across states. While states like Bihar, Punjab, Orissa, West Bengal, and Tamil Nadu have seen an increase in industrial employment, partly driven by the construction sector, the southern states of Kerala, and Karnataka have witnessed the highest increase in the share of employment in services since 2004-05. The largest increase in the working-age population leaving the labour market has been in the three relatively prosperous states – Gujarat, Haryana, Karnataka - and more worryingly in a relatively poor state of Uttar Pradesh, says the report.

Farmers’ issues and the status of Indian farming

2018 – 22

February 17, 2024: The Times of India

From: February 17, 2024: The Times of India

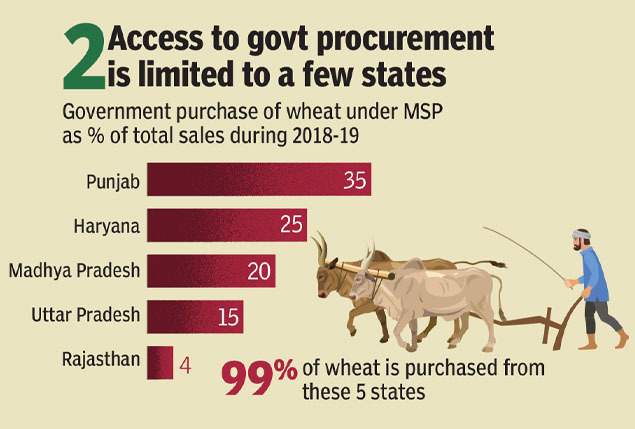

See graphic:

Farmers’ issues and the status of Indian farming, 2018 – 22

Farmers’ agitations in India are almost always about higher price for their output (crops) and lower price for their inputs (example, seed, fertiliser). Here’s why this approach is reaching an end-point and solution to farmers’ real problem requires a different outlook and approach, writes Atul Thakur.

Agitations

History

Jnauary 1, 2021: The Times of India

Mridula Mukherjee taught modern history at JNU. Her area of expertise includes peasant struggles in India and agrarian movements in Punjab. In an email interview with Avijit Ghosh, she links the ongoing farmers’ movement with similar protests in the past:

Which were the major peasant movements of Punjab? Geographically, which areas in the state were the hotspots?

Punjab has a long tradition of peasant protest going back to at least the first decade of the 20th century. Beginning in 1907 with the Swadeshi Movement or Pagri Sambhal O Jatta movement, as it was popularly called in the Punjab, the tradition of peasant or kisan protest was strengthened by the Ghadar movement of 1914-15, the Akali movement from 1920-25, the activities of the Kirti Kisan Party and Naujawan Bharat Sabha, founded by Bhagat Singh in the late 20s, the major national struggles such as the Civil Disobedience Movement of 1930-32 and the Kisan Sabha movements against high land revenue, water rates and indebtedness during the years 1931-36, to name some. In the post-independence period, the biggest movement was in 1958-59 against the imposition of a Betterment Levy to meet the costs of the irrigation part of the Bhakra Nangal project.

Their greatest strength was visible in the Central districts, most of which constitute present day Indian Punjab, followed by the south-eastern part, which is Haryana today. Much of Western Punjab, which went to Pakistan, was home to a very backward, rack-rented tenant population dominated by big feudal landlords, and remained outside the influence of modern politics.

What has been the most recurring cause of peasant discontent?

The most recurring cause of peasant discontent were those government legislations which were seen as adversely affecting peasant interests or those tax demands that were seen as unjust or oppressive by the peasants. In the preindependence period, the movements were also imbued with antiimperialist, or nationalist sentiment, and often peasants participated in movements which had no specific peasant demands, as for example in the Ghadar movement or the Akali movement or the Civil Disobedience Movement, because they were, like other Indians, convinced that British rule had to go if India and Indians were to prosper.

What are the ideological moorings of these movements?

The ideological moorings have been anti-imperialist, secular and egalitarian. Beginning with 1907, the Congress remained the strongest influence, as it represented the most powerful historical urge of the age, that is, anti-imperialist nationalism. The Akalis, of various strands, some pro-Congress, others more loyalist, also were an important force because of the impact of the Akali movement of 1920-25 for the liberation of the Gurdwaras from feudal and loyalist elements, which had involved the Sikh peasants in a big way. From the late 1920s, and especially from the mid 1930s, parties, groups and individuals with left wing ideologies, such as the Kirti-Kisans, Communists, and Congress Socialists emerged as the strongest influence among the peasants.

Bhagat Singh remains a popular figure among farmers. Why?

Bhagat Singh remains a very popular figure because he symbolises the pinnacle of sacrifice for a cause. This is also in keeping with the Sikh tradition of veneration for martyrs, for example, of Guru Tegh Bahadur. Possessing an extraordinary intellect, he proclaimed himself an atheist and a socialist while in jail awaiting his hanging at the age of 23. He is also the nephew of Ajit Singh, the leader of the 1907 Pagri Sambhal O Jatta movement, who was exiled by the British along with Lala Lajpat Rai.

Is there a link between the ongoing farmers’ strike with previous such efforts in the 20th century?

I am surprised by the extraordinary way in which this current protest resonates with the past. The greatgrandparents and grandparents and even parents of some of the older participants fought against government legislation or measures that they did not like, as in 1907, 1934-39, 1946 and 1958-59, demonstrating enormous capacity for struggle and sacrifice.

We even have examples of cultivators revolting against the exploitation by private companies who leased the land. As we witness today, the peasant protest was then too led by an intellectually sophisticated and mature leadership, willing to make tremendous sacrifices. The tradition of contribution by the community, symbolised by the langar, to keep the protest going, is also an old one. Kisan activists would go house to house collecting grain for the langar at the big conferences which were a staple of the movement. Jathas going for a morcha (or struggle) would be fed and housed by villages en route.

2011-20

November 26, 2020: The Times of India

From: November 26, 2020: The Times of India

Why farm protests have become more frequent

NEW DELHI: Armed with sticks and rocks, thousands of farmers from various states are marching towards Delhi to protest against the new farm laws cleared by Parliament in September. The protest march is reminiscent of several agitations held by farmers in recent times over a range of issues, including land allocation deals, loan waivers, suicide rates, and minimum support price (MSP). In fact, India has witnessed a worrying rise in protests, clashes and riots related to agrarian distress over the past few years, shows data.

As per data from 2014 to 2018, there have been more than 13,000 protests by farmers on various agrarian issues. These protests have seen a sharp increase over the years, having escalated by eight times from a little over 600 in 2014 to more than 4,800 in 2016.

Major farm protests, 2011-20

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Government officials admit that frustrated farmers have taken out their anger on the roads in the last couple of years with some major protests reported from states like Madhya Pradesh, Bihar, UP. They said it's due to issues like shrinking of farmlands, failure of crops, poor irrigation facilities, bad seeds, drought, debts etc.

According to 2017 NCRB report, the maximum number of riots related to agrarian distress were reported from Bihar (2,342 cases), almost double the number registered in 2015 (1,156 cases). This was followed by 1,709 riots involving farmers reported from Uttar Pradesh in 2016, while only 752 such incidents were reported from the state in 2015.

A look at the timeline of farmers' protest over the last 10 years show that the minimum support price (MSP) for various crops has been a major grouse. Another issue has been that of land acquisition, with farmers complaining that compensation for land acquired for industrial projects was not in tune with market rates.

Causes

2017: caused by RBI's strong inflation targeting?

`Farmer strikes may have roots in RBI's strong inflation targeting', Jun 10 2017: The Times of India

Food Prices Lower Than Three-Year Average: SBI Report

The recent farmers' agitations across various states may have its roots in the Reserve Bank of India's (RBI's) aggressive stance to target lower retail inflation as this has led to prices, especially of food items, currently being lower than the three-year average.

On the one hand while the government's agri sector reforms are showing results to smoothen out the supply side hurdles, slide in food prices have been much faster because of the RBI's aggressive policies to contain retail inflation, a report by SBI noted.

Food items have about 46% weight in retail infla tion. So to keep the consumer price index (CPI) under the RBI's target of 4%, the rise in food prices should be in the 5-6% range, which has happened at ground level.

Within this category , cereals & products have a 9.7% weight, followed by milk & products with 6.6%, vegetables with 6% and meat & fish with 3.6% weight.

“The interesting part is that even if we compare the October 2016 food prices with the three-year average, the prices have barely moved.This indicates both permanent and transient impact on food prices,“ the report pointed out.

“The permanent factors include the effective supply response by the government in the last three years, while the transient factor is the demonetisation impact,“ the report by Soumya Kanti Ghosh, group chief economic adviser, SBI, pointed out. SBI believes that any rush towards the 4% inflation target “will put further pressure on keeping a vigil on food prices. This is all the more relevant, given the agitations for farm loan waivers in different parts of the country as signs of rural distress, a flip side of the crash in food inflation over the last several months,“ the report noted. “This also shows the dangers of targeting food inflations consistently at very low levels as a part of the overall mandate for inflation targeting without adequate agri reforms.“

‘Farmer agitations reflect clout more than distress’

SA Aiyar, April 8, 2018: The Times of India

The farmers’ march in Maharashtra last month got much sympathy from a public fed on stories of rising farm suicides. But the agitating farmers demanded waivers of all farm loans and electricity dues. Such outrageous demands for freebies may impress politicians wooing the farm lobby, but will not improve justice or fairness.

Rising farmer agitations are not good indicators of rural distress. Rather, they reflect high returns to agitations, increasing the incentive to organise and make new demands. Farm loan waivers have been granted by UP, Maharashtra, Rajasthan, Karnataka and Punjab. Many states provide free farm electricity. Meanwhile non-performing bank loans for agriculture are up from 2% to 6%. One reason is that farmers default, hoping their dues will soon be waived.

The biggest farmers get the biggest bank loans. Marginal farmers and labourers get little or no formal credit, and borrow at extortionate rates from moneylenders. Waiving bank loans will fatten the richest while neglecting those in real need.

Some farm families own hundreds of acres, and one farmer in Punjab has 150 tubewells. Most small farmers have no tubewell at all. So free electricity benefits the biggest and richest farmers. Landless labourers are far poorer than farmers, but get no benefit from loan waivers or free electricity. The Modi government promises higher food prices to help farmers, but this will hit labourers, for whom cheap food is a blessing.

Farmers are a powerful lobby across the world, even in rich industrialised countries like the US. In India, rural areas represent two-thirds of the population and almost half of all employment, so they have much political clout. State governments have been falling over one another to woo the farm vote bank. The fact that loan waivers and free power mostly benefit large farmers and not poor labourers is hardly mentioned in media debates.

One reason is that the public has been fed with stories of rising farm suicides, so nobody wants to be accused of promoting such suicides. Sorry, but there is nothing special about suicide rates of farmers, and they are not rising. The national suicide rate has historically been in the region of 10-11 deaths per one lakh of population, not very different from the rate globally or in rich countries like the US. Indian farmers have a lower suicide rate than non-farmers.

In a 2012 research paper in The Lancet, Vikram Patel and others found that suicides among unemployed persons and those professions outside agriculture were, collectively, thrice as frequent as among farmers and agricultural labourers. Suicide rates are 10 times higher in southern states than northern ones, mainly for cultural reasons. Former Niti Aayog chief Arvind Panagariya showed that barely 25% of rural suicides were farm-related.

Some other studies using a narrow definition of farmers claim that farmers have a higher suicide ratio than others. The question remains whether farmers should be defined as self-cultivators, cultivators plus agricultural workers, or all persons connected with agriculture. Broadly speaking, almost half of Indian households claim to be employed in agriculture. On any broad basis, the farm suicide rate is lower than the non-farmer rate.

Puducherry, with little agriculture, has the highest suicide rate among states, followed by Kerala. This surely has nothing to do with low farm prices. Anuradha Bose in The Lancet in 2004 found that the suicide rate among Tamil girls aged 10-19 was 148 per lakh people. This is over ten times the farm suicide rate, yet the latter hogs the headlines. Depression and mental health are the main causes of suicides, which is why rich nations also suffer, but nobody discusses this problem. Official data shows farm suicides rose from around 11,000 in 1995 to 18,241 in 2004, and then fell substantially. Farm suicides fell to 12,602 in 2015 and 11,370 in 2016. This is hardly 8% of total suicides, although almost 50% of the population is engaged in farming. The accuracy of suicide data can be questioned, but the overall trend shows declining, not rising distress.

A reply to a Lok Sabha question showed suicides rising among agricultural labourers (from 4,595 in 2015 to 5,019 in 2016) even as they fell among land-owning farmers (from 8,007 to 6,351). This suggests rural distress is greater among labourers than farmers.

Let me repeat a suggestion made in an earlier Swaminomics column. If farmers are to be aided, the best way is a flat subsidy of Rs 4,000 per acre per cropping season, up to a limit of five acres, while ending other subsidies. This will provide a safety net without distorting farm prices and production.

The agitation of 2020

See Farmers' agitation, 2020-21: India

The root cause

Bloomberg, February 13, 2021: The Times of India

The root of the conflict lies in a system that evolved over more than half a century after the Green Revolution of the 1960s slowly transformed the nation from a land of frequent famines to an agricultural powerhouse. India is now the world’s biggest exporter of rice and the second-largest producer of wheat and sugar. At the same time, a complex and inefficient system of state support, controlled markets and government welfare grew up that Modi is trying to unpick.

Under the present system, the government sets minimum prices for about two dozen crops and buys large volumes of rice and wheat for its welfare programs. While traders aren’t legally obliged to pay the government-set rates, the sheer volume of state purchases creates de facto price support for key grains from small farmers, who sell their produce through licensed traders in designated markets. These markets were set up to open up the industry and prevent exploitation of smallholders, but over time many became effective monopolies, with traders pulling together to stifle competition. As a result, prices of rice and wheat have remained stable over years, while other crops such as soybeans, corn and rapeseed have seen sharp price swings.

Farmers like the arrangement because the government provides them with a guaranteed buyer, allowing them to easily secure informal short-term loans to buy farm inputs like seeds in a country where rural banking services are often inadequate.

The new rules intend to liberalize trading by allowing farmers to sell crops outside the designated markets. Modi’s administration has promised that the welfare support mechanism will remain, but protesters aren’t convinced.

Many believe the reforms are designed ultimately to cut the government’s food subsidy bill— expected to be $33.4 billion in 2021-22— by allowing market forces to drive down prices. The current support rates reflect the cost of production plus a 50% profit, which, along with assured purchases, has encouraged farmers to overproduce some crops. With India growing more wheat, rice, sugar cane and cotton than it needs, a free-for-all could cause prices to slump.

Worse still, 86% of India’s farmers cultivate plots of about 2 hectares (5 acres) or less, while the other 14% own more than half the cultivated land. In an unfettered market, large landowners with lower costs per acre and better access to funds could end up dominating markets, forcing smallholders to sell their land. That’s a shift that took decades in many developed nations as rural residents migrated to cities to work in factories. But an accelerated transition on the scale of India’s population risks a major humanitarian crisis.

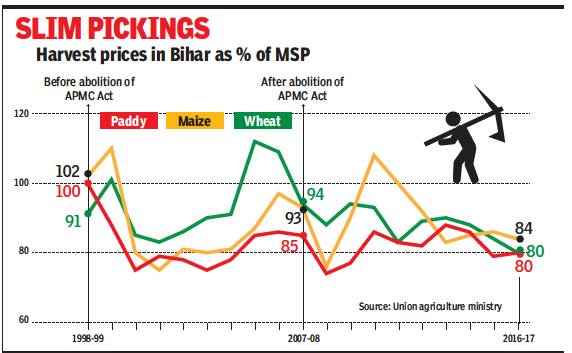

Migrating Farmers

Jokhu Ray, who grew corn and rice in the eastern state of Bihar, has had a taste of what a free market could mean. Bihar abolished its government-managed market in 2006 and Ray says the result was disastrous for him. In the 2019-20 crop year, he could only get 10 rupees (14 cents) a kilogram for his corn, less than the support price of 17.6 rupees or the 15 rupees he got the year before. Like many others, Ray left his village to seek work elsewhere and now works on a construction site in Rajasthan.

Stories like Ray’s have fueled farmers’ fears. Protesters around the country held 3-hour “chakka jams” at the weekend, holding up traffic. The government blocked the internet at major protest sites and deployed some 50,000 police and paramilitary, along with riot control vehicles in and around Delhi, according to local media. After violence broke out at a Republic Day rally in the capital in January, the United Nations urged farmers to keep protests peaceful.

“The government has shut down the Internet here out of fear,” said Singh, by phone. “We are not scared. We are informing people through phone calls.”

“We are urging those involved in agitation to end protests,” Modi told lawmakers in parliament on Feb. 8. “We should give these agriculture reforms a chance.”

Farmers instead are demanding new legislation that makes it illegal to pay less than the minimum support rate, a policy analysts say would distort the market even more. Private buyers could be scared off, forcing the government to have to step in and buy even more. That would worsen a fiscal deficit that is already expected to widen to 9.5% of GDP due to the coronavirus.

State-run Food Corp. of India, the nation’s biggest food-grain buyer, is already stretched after buying 39 million tons of wheat and 52 million tons of rice from last year’s crop of about 108 million tons and 118 million tons respectively. Recent bumper harvests have filled many state granaries to bursting.

Raising minimum prices each year could also hit exports, said B.V. Krishna Rao, president of the nation’s Rice Exporters Association. “The moment we make minimum prices a legal obligation, we are bound to lose our share in the global market.” He suggested that support prices should be set close to global levels and farmers compensated if needed for any losses.

And there are other, even more serious long-term consequences if India doesn’t find an equitable way to reform its agriculture, especially in states like Punjab and Haryana, where the protests began.

Green Revolution

India’s Green Revolution in the 1960s brought a surge in grain output in Punjab thanks to high-yielding seeds, mechanization and increased application of pesticides and fertilizers. Known as India’s bread-basket, the state supplied about one third of the 62 million tons of water-intensive paddy that the government purchased from monsoon-sown crops so far this year, according to the food ministry.

“States like Punjab grow more rice than they consume despite unfavorable terrain, which has resulted in a drastic depletion of their water tables,” Rini Sen, an economist with ANZ Banking Group, said in a report.

India has only about 4% of the world’s fresh water and farmers tap almost 90% of the groundwater available. Growers say they can’t afford to switch from water-intensive crops such as rice and sugar cane unless the government ensures the same kind of price support for more sustainable crops like soybeans, mustard or pigeon peas (used to make dal).

Finding a compromise that would reassure farmers they can still make a decent living while dismantling an archaic and inefficient agriculture market may be Modi’s hardest task to date. But as the two sides dig in for what could be a long and bitter stand-off, it’s one that India must solve.

The agrarian crisis and the political class

May 11, 2015

Ravish Tiwari

The political class has read the agrarian crisis wrong. It's about time rhetoric met reality

Gajendra Singh : In his death, Gajendra Singh gave the political class much to outrage over. And outrage they expressed, but mostly over the wrong reasons. The middle-aged man from a farming family in Rajasthan's Dausa district hanged himself at a farmers' rally organised by Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal at Jantar Mantar on April 22, 2015. Almost immediately, the televised suicide was taken over by the opposition parties to rail against the Narendra Modi government's land acquisition ordinance, equating Singh's death, and those of other farmers, with the law.

There's very little, however, to suggest any connection between land acquisition and either the rising level of agrarian crisis or the overall number of farmers who took their own lives. And those numbers have in fact declined in the last 10 years until 2013, says the National Crime Records Bureau. But in their attempt to score brownie points, the politicians seemed to be barking up the wrong tree. Discussions in both houses of Parliament focused mostly on easy solutions to the crises, virtually ignoring deeper structural issues that need political solutions.

Not that agrarian crisis is a non-issue. Far from it. The 2011 Census estimates 168 million of India's total 247 million households are in rural areas. The "Situation Assessment Survey of Agricultural Households", conducted during the 70th round of the National Sample Survey Office (NSSO) held in 2013, says only 90.2 million of those 168 million rural households are engaged in agriculturally productive operations. But that's not the problem. The assessment survey suggests that farmers involved in farming operations on land up to 2 hectares (ha)-the small or marginal farmers-cannot meet even their average monthly consumption expenditure from only incomes generated from farming (cultivation and animal husbandry). It says as many as 78.1 million of the 90.2 million farming households (86.6 per cent) do not earn enough from farming to meet their expenses. And that is where the problem lies.

Fragmented ownership

A NABARD paper released in February 2015 suggested that the average size of operational landholdings has reduced by half in the last 40 years-from 2.28 ha in 1970-71 to 1.16 ha in 2010-11. As a result, the number of landholdings in the marginal and small categories have swelled by 56 million and 11 million, respectively. NABARD's assessment of unviability of smaller farms, in a way, has been validated by NSSO survey results made public in December 2014, which say only farms more than 2 ha are yielding more income than farmers' consumption expenditure.

The solution then lies in arresting this fragmentation and consolidation of farms-a task the political class needs to take up forthwith. "The answer lies in farmers getting together to collectivise farmlands; not Soviet collectivisation but taking the shape of producer companies. (It requires a) limited form of cooperation where a farmer does not give his land away but cooperates for input purchases and selling of the produce," says noted agricultural economist Y.K. Alagh.

Ramesh Chand, director, National Centre for Agricultural Economics and Policy Research (NCAP), suggests a regulatory framework to facilitate legal leasing of farmland to ensure security and stability for farmers. India's land lease laws are based on conditions dating back to Independence, which makes many farmers unwilling to lease out land. "Or those who want to take farms on lease don't get it," Chand says. "Farmers prefer to keep land fallow rather than lease them out; they fear they would lose control."

For the political class, the challenge lies in fragmentation of landholdings that are getting unviable. Agriculture administrators recommend proliferation of oral or informal leasing/renting of farmland to advocate a legal framework to protect landowners and facilitate consolidation of landholdings.

Race for insurance

If this was the winter of discontent for farmers in most parts of north India, the spring arrived with little hope. The unseasonal rain and hailstorm in patches ravaged standing crops on nearly 189 lakh ha of about 606 lakh ha of rabi acreage. The twin demands that arose as a result were of central relief by state governments and relaxation of procurement norms by farmers to ensure their spoilt crop is assured of a market.

As expected, the political rhetoric has hit the high notes: in Parliament, ruling NDA MPs were keen to highlight the Centre's call to relax relief disbursement norms, while the Opposition panned the government for its failure to release more funds to states promptly. Lost in this politicking was the fine difference between relief and compensation. Lesson for politicians: the Centre provides relief if crops fail, but the need of the hour is to insure them.

Farmers are hardly out of the woods once the yield comes out good and is harvested. The next part of the harrowing journey only begins then. And one merely needs to follow the Gangetic plain eastward to hear complaints of farmers in Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and West Bengal about their produce remaining unsold, or being sold below the minimum support price (MSP).

"Farm holdings are so fragmented in eastern India that farmers find little merit in incurring transportation cost to procurement centres. This allows aggregators, traders to purchase the produce at the farm gate instead of the mandi (wholesale), and that is usually below the MSP," says Ashish Bahuguna, former agriculture secretary.

While the political leadership of Punjab and Haryana, the original Green Revolution states, have institutionalised their procurement networks, political leaders elsewhere, especially in the Gangetic plain, need to learn a lesson from Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh Chief Ministers Shivraj Singh Chouhan and Raman Singh respectively. The two CMs have given a sustained push to a sound procurement network for wheat (MP) and paddy (Chhattisgarh) farmers, and thereby good price for their crops.

Not unlike the politicians, the prevailing laws also do not help much. Both the Agricultural Produce Market Committee Acts and the Essential Commodities Act have patronised traditional and entrenched traders and have not allowed modern trading, and need to be amended. Political leaders need to mull over how to modernise domestic trade to facilitate modern capital infusion to create logistics and storage facilities.

Fight for inputs

The entire political class may take pride in India's agricultural tradition, but most farmers still continue to struggle for basic inputs such as seeds, fertiliser pesticide, irrigation, power and credit. There was a large-scale disruption in fertiliser supply only last year, raising the political heat in several parts. "Inputs such as seed and fertiliser need to be available on time. Fertiliser requirements for kharif crops should be tied up at the end of the previous rabi crop," points out Gurbachan Singh, for-mer federal agriculture commissioner and now chairman of the Agricultural Scientists Recruitment Board.

"The political class should be alive to the demand forecast rather than react to a crisis generated by (their) misgovernance. Political pressure should ensure proactive coordination between placing orders, ensuring movement (of fertiliser) and timely distribution," says Ajay Vir Jakhar, chairman, Bharat Krishak Samaj.

The political class also needs to learn from state governments such as Shivraj Singh Chouhan's to expand irrigation coverage to reach the benefits to farmers. Similarly, for power supply for irrigation and other operations they need to look at Rajasthan, Gujarat, Andhra Pradesh, Haryana, Punjab, Karnataka, Maharashtra and Madhya Pradesh, which have demonstrated efficacy of separate agricultural feeders for farmers.

As for agriculture credit, though it has jumped to more than Rs 8 lakh crore, Ramesh Chand underlines the wide inequality in institutional credit between states.

There's a lot to be learnt for politicians to address the varied crises farmers face. As India looks at a year of below-normal monsoon, it's important that they show outrage over deaths such as that of Gajendra Singh's. But that fury has to be for the right reason for it to have any lasting effect.

Political parties unaccountable to farmers

Apr 27 2015

Dhananjay Mahapatra

Parties must rise above politics over farmer deaths

We have been told that agriculture is the mainstay of the Indian economy . Monsoon gives life to agriculture. The agricultural workforce reinforces India's granaries and ensures its food security . If agriculture occupies a pivotal role, why have governments in 65 years not been able to improve the plight of the farm workforce? At the same time, land owners have flourished. They own huge tracts of land, which helps them acquire money , muscle and political influence. In contrast, farmers have remained on the fringes. Over the years, ruling parties have tom-tommed policy decisions to sanction easy farm loans and later, write them off. Who benefits the land owners or the farmers? To take a loan, a farmer has to show that he has land. A small percentage of farmers own land. So, loans are cornered by land owners. When loans are written off, its double benefit for them.

Most land owners give their land for farming on contract basis. The usual contract is the farmer will till the land, sow the seeds, water the crop and look after it. At harvest time, the land owner will take either onethird or half the crop. To buy seeds, fertilizer and other farm requirements, the farmer needs money . He takes loan, not from banks but village money-lenders at hefty rate of interest. Given the inadequate irrigation system, most farmers feel the heat in a bad monsoon year. Failed crop means loan defaults. Spiraling interest soon overtakes the principal, due to which the trapped farmers seek release by embracing death.

A farmer's death at the AAP rally at Jantar Mantar showed us yet again the eagerness of parties to score brownie points, unmindful of the fact that our policies have failed to ensure a better life for those who take care of our food and fill our granaries.

All parties behaved as if this death exemplified the present situation of farmers.Irrespective of the party in government in various states, thousands of farmers have ended their lives over the years to escape the debt trap. The party which sold dreams to hitch a ride to power says it is not even a year-old and blames the previous party which was in power. But no one has given a concrete policy framework providing farmers an honourable release from the debt trap.

The farmers' plight was explained vividly by the Supreme Court in its December 14, 2010 judgment in Maha rashtra vs Sarangdhar Singh Shivda Singh Chavan case. It was about the illegal money lending (at the rate of 10% interest a month) racket in Maharashtra. The petitioners said, “Nearly 300 farmers have committed suicide in Vidarbha as victims of such illegal money lending business and the torture perpetrated by the recovery of such money . A complaint has been made that the farmers do not get the benefit of various packages announced by the government and the state machinery is ruthless against farmers.“

The collector of Buldhana, on instructions of the then Congress CM, had ordered non-registration of police case against a money lender, Gukulchand Sananda, and his family , despite 50 complaints against them.The SC had sought explanation from the ex-CM, who in 2010 was Union minister for heavy industries. The exCM didn't deny the charge of his office asking the collector not to register a case against the Sananda family .

The SC quoted National Crime Records Bureau data to say that nearly 2 lakh farmers committed suicide in India between 1997 and 2008. Two-thirds of the 2 lakh suicides took place in five states Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, MP and Chhattisgarh. The SC drew a pathetic contrast, saying, “Even though Maharashtra is one of the richest states in the country and 25,000 of India's one lakh millionaires reside in its capital Mumbai, the Vidarbha region is today the worst place in the whole country for farmers. The position is so pathetic in Vidarbha region that families are holding funerals and weddings at the same time and some times on the same day .“

In the verdict's concluding paragraph, the SC had said, “This court is extremely anguished to see that such an instruction could come from the chief minister of a state which is governed under a Constitution which resolves to constitute India into a socialist, secular, democratic republic. CM's instructions are so incongruous and anachronistic, being in defiance of all logic and reason, that our conscience is deeply disturbed.We condemn the same in no uncertain terms.“

Such serious judicial condemnation did not cast any shadow on the politician's career. He merrily continued in the UPA cabinet. None he himself, his party or the prime minister -suffered any moral pang.

“ BJP’s rural votes indicate farm crisis exaggerated”: 2018-19

SWAMINATHAN S ANKLESARIA AIYAR, June 2, 2019: The Times of India

BJP’s rural votes show talk of farm crisis misleading

Annual GDP growth fell from 6.9% in 2017-18 to 6.8% in 2018-19. Worse, GDP in the latest January-March 2019 quarter slowed to just 5.8%. Yet Narendra Modi swept the general election. The BJP’s national vote share rose from 31.3% to 37.5%. In the seats it contested, its vote share rose to 46%. Contradicting conventional wisdom on agrarian distress, the BJP actually boosted its vote share in rural areas to roughly 46%, double the Congress’ 23%.

This suggests that talk of agrarian distress is much exaggerated. The latest data shows that agricultural growth in 2018-19 was 2.9%. Growth fell quarter after quarter — 5.1%, 4.9%, 2.8% and -0.1%. Clearly a good rabi and summer crop in 2018 was followed by serious slowing because of drought.

But the annual average of 2.9% is the highest ever in a drought year. This heart-warming achievement reflects increasing irrigation plus diversification into animal husbandry, fisheries and tree crops that are less monsoon-dependent. Indeed, traditional crops now account for barely half the agricultural output. Maharashtra was the worst-hit drought state in India, yet the NDA won 41 of the 48 seats there, and the Congress only one.

Congress apologists argue that Modi diverted voter attention from agrarian distress to the Balakot bombing, highlighting the need for a strongman to enhance national security. But the very fact that economic issues could so easily be overwhelmed by security issues proves that the economy is not in such bad shape. Yes, there is a slowdown. That always causes some pain. But it does not amount to a crisis. That word is seriously overused.

No country has managed more than 3% agricultural growth over a long period. The main reason is that you can build more factories to boost industry and more offices to boost services, but you cannot create more land to expand agriculture. Indeed, with growing urbanisation, India’s cultivated area is falling. So, all gains have to come from higher productivity.

Globally, agricultural productivity has grown historically at barely 2% a year. India’s potential is higher than in some other countries because of catch-up possibilities. Yields in India are far below those in China or Egypt. Even so, calling India’s agricultural growth of 2.5 -3% in the last decade an “agrarian crisis” is simply wrong.

Between 2004-05 and 2011-12, India raised 138 million people above the poverty line. We still await the 2017-18 data. But the World Poverty Clock, an internationally recognised source of quick estimates, says the number in India below the World Bank’s poverty line of $1.90 per day has fallen from 218 million in 2011-12 to barely 50 million in 2018. That would be impossible if India really had an agrarian crisis.

Farmer agitations have risen. They are equally common in rich countries where farmers earn 100 times more. Rising agitations reflect rising returns from demonstrations as governments give in, not distress. Distress was worst in the twin droughts of 1965-66 but there were no agitations, just starvation.

The main rural problem is that rising population has reduced the average farm size to 1-2 acres. Prosperity on such tiny plots is impossible. Agriculture accounts for barely 13% of GDP today but almost 50% of employment. The answer is to move people massively out of agriculture into industry and services.

India has failed there. Its labour laws have prevented the emergence of giant factories (as in China and Bangladesh) with tens of thousands of workers. So, ironically, the biggest rural problem is labour legislation. A massive shift of people out of agriculture would help double or triple farm size.

In poor Bihar and eastern UP, villagers say farming and MNREGA occupies them for only a few months in the year. This looks insufficient to account for rising ownership of cellphones, TVs and motor cycles. Villagers say this is explained by virtually every rural family having one or more members working in a town, often within commuting distance, sending or bringing home remittances. This rural diversification is not captured by statistics. Besides, the arrival of roads, electricity and telecom in almost all villages has created many new rural economic opportunities, from dhabas and repair shops to agro-processing. Doubtless Modi’s charisma is the overwhelming reason for the BJP’s electoral success. It lost state elections in Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh five months ago when voters were choosing a chief minister. But even there the BJP vote share was almost as high as the Congress. There is indeed short-term distress because of the drought and long-term distress because of shrinking land per person. But to call this a crisis is very misleading. Modi’s victory proves that.

Agrarian crises, flashpoints, distress signals

As in 2018

Surojit Gupta, 10 REASONS WHY FARMERS ARE IN DISTRESS, December 13, 2018: The Times of India

Value of agricultural output

Value of manufacturing production

Share of agriculture & manufacturing in states' GDP

Per capita GDP

From: Surojit Gupta, 10 REASONS WHY FARMERS ARE IN DISTRESS, December 13, 2018: The Times of India

1 Two years of drought

Two successive years of drought (2014, 2015) have taken a toll on the farm sector. The government has allocated significant funds for the sector but slow implementation of projects has not eased the pain. Drought in Maharashtra, Gujarat and Karnataka have also added to farmers’ woes

2 Collapsing farm prices

Prices have collapsed for farm commodities. Low international prices have meant exports have been hit while imports have hurt prices at home. For example, there was a bumper production of pulses in 2016-17 but imports of nearly 6.6 million tonnes arrived, compounding the problem. In 2017-18, another 5.6 million tonnes flowed in, depressing domestic prices further. The government delayed imposing tariffs on imports, which heightened the problem of prices for farmers. According to a Niti Aayog paper, on average, farmers do not realise remunerative prices due to limited reach of the minimum support prices (MSP) and an agricultural marketing system that delivers only a small fraction of the final price to the actual farmer

3 Insurance fails to serve

The Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana was launched in 2016 to provide insurance and financial support to farmers in the event of failure of any crops due to natural calamities, pests and diseases. It was also meant to stabilise the income of farmers and ensure they remain in farming. But the scheme has seen lower enrolments due to a string of factors, including high premiums and lack of innovation by insurance firms

4 Irrigation takes a hit

Irrigation is crucial for the farm sector, where large tracts of land still depend on monsoon rains. The Centre launched the Rs 40,000-crore Long-Term Irrigation Fund, operated by the National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (Nabard). Under this programme, 99 large irrigation projects were to be completed by December 2019 but the progress so far has been limited. Experts say a number of factors, including bureaucratic delays and slow implementation by states, have hurt progress for this crucial input

5 Marketing is ignored According to a Niti Aayog document, farm sector development has ignored the potential of marketing. Archaic laws still hobble the sector. Access of farmers to well-developed markets remains an issue although several initiatives have been launched to develop an electronic market place. Reforms to the APMC Act have been slow and most states have dragged their feet on it. Experts suggest an entity such as the GST Council to bring together states and the Centre to jointly take decisions to reform the sector and provide better access to markets for farmers. According to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the combination of market regulations and infrastructure deficiencies leads to a price depressing effect on the sector

6 Modern tech missing

Introduction of latest technology has been limited due to a number of reasons. Access to modern technology could act as a boost to productivity through improved variety of seeds, farm implements and farming technology. According to a Niti Aayog paper, there has been no real technological breakthrough in recent times

7 Fragmented supply chains

Large gaps in storage, cold chains and limited connectivity have added to the woes of farmers. It has also added to the significant post-harvest losses of fruit and vegetables, estimated at 4% to 16% of the total output, according to the OECD

8 Lack of food processing clusters

This has meant that there is little incentives for farmers to diversify. According to an OECD document, share of high-value sectors in food processing is low with fruit, vegetable and meat products accounting for 5% and 8% of the total value of output compared to cerealbased products at 21% and oilseeds at 18%

9 Delayed FCI reforms

A government-appointed panel had recommended that FCI hand over all procurement operations of wheat, paddy and rice to states that have gained sufficient experience in this regard and have created reasonable infrastructure for procurement. These states are Andhra Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Haryana, Madhya Pradesh. It had suggested a complete overhaul of FCI and recommended that farmers be given direct cash subsidy (of about Rs 7000/ha) and fertiliser sector deregulated. The panel had said direct cash subsidy to farmers will go a long way to help those who take loans from money lenders at exorbitant interest rates to buy fertilisers or other inputs, thus relieving some distress in the agrarian sector. The report has been put in cold storage

10 Low productivity

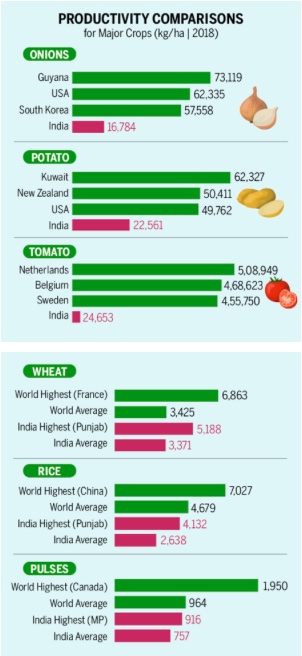

The share of the farm sector in GDP has declined from 29% in 1990 to about 17% in 2016, but it remains a major source of employment. According to OECD data, 85% of operational land holdings are less than 2 hectares and account for 45% of the total cropped area. Only 5% of farmers work on land holding larger than 4 hectares, according to the Agricultural Census, 2016. Productivity lags other Asian economies such as China, Vietnam and Thailand and average yields are low compared to other global producers. Wheat and rice yields are nearly 3 times lower than world yields while those for mango, banana, onion or potato are between 2 and 7 times lower than the highest yields achieved globally, according to the OECD

=Agribusiness/ Agriculture business

Some possibilities, as in 2020

Prabhu Pingali and Mathew Abraham, December 26, 2020: The Times of India

As India continues its rapid urbanisation, supplying cities and district towns with food provides a new growth opportunity for rural areas. Urbanfacing agribusinesses and value chains offer employment opportunities in aggregation, logistics, storage and processing. In city centres, food-related services such as restaurants, organised retail, and food delivery will increase in importance as a channel of employment generation.

Coupled with income and population growth, urbanisation is also changing food preferences. The share of rice and wheat in Indian diets has declined, while the consumption of fruits, vegetables, and livestock products has increased. According to NSSO surveys, monthly expenditure on cereals and cereal products fell from 41.1% to 10.8% in rural India and from 23.4% to 6.6% in urban areas between 1971-72 and 2011-12.

The rising demand for diversified agricultural products is an opportunity for smallholder farmers to commercialise, improving agricultural incomes and nutritional status at the household level. However, smallholders face obstacles in accessing credit, purchased inputs, technology and extension services to produce the quality required for urban consumption.

High transaction costs resulting from a low volume of produce, poor connectivity to markets, difficulty finding buyers and low bargaining power limit their market participation. This empowers intermediaries, who purchase from farmers at the lowest competitive price at the farmgate and sell in markets in their stead.

India’s market structure has long favoured staple grains. MSP incentivises farmers to grow staples and the APMC enables procurement into PDS, ensuring a productivity increase in staple grains. But the system is inadequate for marketing higher value crops. Only 6% of Indian farmers benefit from the MSP, and there are few alternative value chains for quality, high-value produce.

Though permitted in 2003, onerous requirements and fees have limited contract farming, except for a few crops like cotton and barley. The most significant challenges have been collective action problems of companies having to form contracts with hundreds of small farmers in informal groups, poor contract compliance by buyer or seller with low accountability, and the limitation of procuring from the area of a particular market’s jurisdiction.

The Producer Companies Act of 2002 made provisions for small producers’ aggregation into companies, allowing farmers to jointly access inputs, credit, farm machinery, and together sell in the markets. These FPOs can address contracting and adherences problems in contract farming with small farms. Although the initial uptake has been slow, government schemes and corporate, NGO, and private foundation interests have led to a rapid increase in FPO formation. Only 445 FPOs were registered in 2013, but since 2016, over 5,881 have been registered.

Despite the increased focus, success stories have been few. The extended gestation period required for FPOs to become self-sustaining, limited financing opportunities, weak linkages to markets, high coordination costs, and inadequate managerial expertise remain significant challenges.

This is where the FPTC and FAPAFS acts play essential roles. FPTC allows the creation of ‘trade areas’ where any corporate buyer, processor, private trader, or agri-entrepreneur can buy directly from farmers. Referred to as the ‘Contract Farming Bill’, FAPAFS allows for noncompulsory written contracts between buyer and seller across the country, beyond the purview of APMCs. While this freedom is a welcome change, FAPAFS excludes land leasing and prevents sponsors from constructing structures on farmland.

The easing of market restrictions will result in a private sector response in agricultural value chains. Cold chains, better connectivity, the establishment of grades and standards, and storage infrastructure will be in the private sector’s best interest while linking directly to farms. But without strong FPOs, FAPAFS and FPTC will do little to improve smallholder market access by themselves.

Prabhu Pingali is Director, Mathew Abraham is Assistant Director of Tata-Cornell Institute for Agriculture and Nutrition, Cornell University

Agriculture census

2010-11

9th December 2018: Press Information Bureau

Department of Agriculture, Cooperation& Farmers Welfare has released Agriculture Census 2010-11(Phase-II). Highlights of the Census are:

Highlights

As per Agriculture Census 2010-11,

· Total number of operational holdings were estimated as 138.35 million.

· The total operated area was 159.59 million hectare.

· The average size of the holding has been estimated as 1.15 hectare. The average size of holdings has shown a steady declining trend over various Agriculture Censuses since, 1970-71.

· The Size Group wise percentage of number and area of operational holdings are given in the following table.

|

Sl.No |

Size-Group |

Percentage of number of operational holdings to total |

Percentage of area operated to total |

|

1 |

Marginal (below 1.00 ha.) |

67.10 |

22.50 |

|

2 |

Small (1.00 - 2.00 ha.) |

17.91 |

22.08 |

|

3 |

Semi-medium (2.00 - 4.00 ha.) |

10.04 |

23.63 |

|

4 |

Medium (4.00 - 10.00 ha.) |

4.25 |

21.20 |

|

5 |

Large (10.00 ha. & above) |

0.70 |

10.59 |

· The Gross Cropped Area (GCA) was estimated at 193.76 million hectare.

· The nine States, viz., Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Punjab, and West Bengal together account for about 78 per cent of the Gross Cropped Area in the country.

· Out of the total 64.57 million hectare Net Irrigated Area, 48.16 percent is accounted by Small and Marginal holdings, 43.77 percent by Semi-medium & Medium holdings and 8.07 percent by Large holdings.

· The Cropping Intensity as per Agriculture Census 2010-11 works out to 1.37.

· For 96.95 per cent of operational holdings, entire operated area was located within the village of residence.

· Among various sources of irrigation, Tube-wells was main source of irrigation followed by canals.

All India level, during 2010-11, the proportion of net irrigated area to net area sown was 45.70 percent.

Agriculture Census in India is conducted at five yearly intervals for collection of information about structural aspects of agricultural holdings in the country. The basic statistical unit for data collection is ‘Operational Holding’. The reference year for the present Census was Agriculture Year 2010-11 (July-June). Agriculture Census data is collected in three phases. During Phase-I, data is collected on primary characteristics such as number and area of operational holdings. In Phase-II, detailed data is collected on sample basis from 20 per cent villages covering characteristics such as tenancy, land use, irrigation, cropping pattern, dispersal of holding etc. During Phase-III, generally referred to as Input Survey, data is collected on pattern of use of inputs.

|

Sl.No. |

Category |

Operated Area |

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

|

1 |

Marginal holdings |

Below 1.00 hectare |

|

2 |

Small holdings |

1.00 -2.00 hectares |

|

3 |

Semi-Medium holdings |

2.00 - 4.00 hectares |

|

4 |

Medium holdings |

4.00 - 10.00 hectares |

|

5 |

Large holdings |

10.00 hectares and above |

The concept of agricultural operational holdings does not include those holdings which are not operating any agricultural land and are engaged exclusively in livestock, poultry and fishing etc. On the basis of operated area, operational holdings in Agriculture Census are categorized as follows:-

The results of Phase-I and Phase-II of Agriculture Census 2010-11 have already been finalized and released. The detailed data /tables of Agriculture Census are available in the website of the Department at http://agcensus.nic.in. The All India Report of Agriculture Census 2010-11 is based on the data collected during Phase-II of the Census.

1970-2016: farm size shrinks, women landowners rise

From: Vishwa Mohan, Slide in farm size, but women landowners rise: Agri census, October 2, 2018: The Times of India

The increase in farmland holdings, a consistent trend since the 1970s, has been slowing down in the past 20 years but there is a rise in the number of female landholders, a possible indicator of higher involvement in farm activities, the provisional agriculture census 2015-16, has revealed.

The trend could mean the association of farming with “kisan bhai (farmer brothers)” might be less exclusively a male domain than popular belief has it. The trend may reflect migration of men to cities for non-agricultural activities and also explain slowing down of land division as rural people seek alternate livelihoods.

The figures show landholdings have doubled in past 45 years (from 71million in 1970-71 to 146 million in 2015-16), resulting in decline in average size of farms by more than 50% — a real worry for policy-makers as this makes agriculture unremunerative for farmers.

But the pace of such division is declining. Number of land holdings increased by 12% from 1995-96 to 2000-01, 7.5 % after that till 2005-06, 6.9% by 2010-11and 5.33% till 2015-16.

The agriculture census is carried out at five-year intervals as part of the world agriculture census programme. The first census in India was conducted in 1970-71. Data provides valuable inputs to policy makers as they plan various intervention.

The current agriculture census is the 10th in the series whose final figures, comprising other details, are expected to be released by December. According to provisional data, the percentage share of female land holders increased from 12.79% (17.65 million) in 2010-11 to 13.87% (20.25 million) in 2015-16. Their numbers were nearly 11% ( 15.11 million) in 2005-06.

Decreasing size of land holdings, however, remains a serious challenge. Being the final unit for agriculture-related decisions, an operational holding has been taken as statistical unit at micro-level for various policy interventions.

Landholdings

Vishwa Mohan, UP to gain most from PM’s farm proposal, February 3, 2019: The Times of India

From: Vishwa Mohan, UP to gain most from PM’s farm proposal, February 3, 2019: The Times of India

In Percentage Terms, Kerala Top Beneficiary

Uttar Pradesh may be the biggest beneficiary of the Centre’s assured income support programme due to sheer number of small and marginal landholders in the state, but it is Kerala which figures at the top if one looks at the data in percentage term as over 99% of the farmers there have landholdings of less than five acres.

Under the income support programme (PM-KISAN), announced in the government’s interim budget on Friday, the Centre will annually provide Rs 6,000 each to only those over 12 crore landholders who have cultivable land of less than five acres (two hectares).

State-wise figures of such landholders show that over 50% of total beneficiaries will collectively be from five states with the highest of them (2.21 crore) coming from UP, followed by Bihar (1.59 crore), Maharashtra (1.18 crore), MP and Andhra Pradesh (over 75 lakh each). Over 80% of total beneficiaries will come from 10 states where Kerala figures at the top in percentage terms followed by Bihar, West Bengal, UP and Tamil Nadu. Except Bihar and West Bengal, all the states in the list along with Telangana have adequate digital land records.

These figures are part of the 2015-16 agriculture census, released late last year, which will be the basis of implementing the assured income support programme while arriving at corroborative land data.

Union agriculture minister Radha Mohan Singh confirmed to TOI about making the 2015-16 census as the basis of implementing the programme. The ministry on Friday wrote to all states asking them to share their digital land data base comprising details of beneficiaries including name, gender and SC/ST status. States which don’t have complete records in digital formats may share their data of beneficiaries of various schemes.

The Centre will issue detailed guidelines for the implementation of the scheme in the next two-three days and appoint link officers in agriculture ministry for each state for monitoring.

Asked how the Centre would arrive at exact data of beneficiaries for properly implementing the scheme, additional secretary in agriculture ministry Ashok Dalwai said, “It’ll be implemented through electronic medium so that money is transferred directly to the farmers’ ‘Jan Dhan’ accounts”.

Agriculture reforms

The best performing states, 2015

Maha tops Niti Aayog's agriculture reforms index. Nov 01 2016 : The Times of India

66% Of States Fail To Reach Half Way Mark

Maharashtra is on top of the ladder, followed by Gujarat and Rajasthan, in Niti Aayog's index reflecting states' performance in undertaking agriculture and farm sector reforms.

The first-ever such index, by Niti Aayog, is aimed at ranking states on the basis of implementing agriculture marketing reforms and ease of doing agri-business.

States like Bihar, Kerala and Manipur are not included in the ranking because they either did not adopt Agricultural produce market committee (APMC) or revoked it. “We are talking to them as we think this is not the best thing to do,“ said Ramesh Chand, member of Niti Aayog. Almost two-third of the states could not reach even half way mark of reform score of the index. Major states like UP , Punjab, West Bengal, Assam, Jharkhand, Tamil Nadu and J&K, have poorly performed .

As per the states' score in the in dex, Madhya Pradesh ranked fourth, followed by Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Telangana, Goa and Chhattisgarh.An official said, “The index is aimed at helping the states to identify and address problems in the farm sector, which suffers from low growth, low income and agrarian distress.“

Stressing on urgent need to push reforms in the farm sector, Niti Aayog vice-chairman Arvind Panagariya said that post 1991, reforms focused on non-agriculture sector. “Reforms did not focus on the agri sector. One effort was made in 2003 through the model APMC Act reform and some progress was made but not enough and that has led to gap between industry and services on one hand and agri on other hand,“ he added.

The areas identified by Niti Aayog with a view to double farm income include agriculture market reforms, land lease reform, and reforms related to forestry on private land.

Use of modern techniques

The Times of India, Apr 27 2015

Between the 1940s and 1960s, research helped many countries increase agricultural yields. The yield per hectare is an indicator of the use of modern techniques like mechanisation and use of high-yielding varieties as well as improvement of traditional infrastructure like irrigation. The World Bank includes wheat, rice, maize, barley, oats, rye, millet, sorghum, buckwheat and mixed grains to calculate cereal yields. A comparison of India with other major economies shows that India's cereal yield is among the lowest. In 2013, cereal yield in the US was about two and half times that of India.

‘Big’ landholders

2015-16

Vishwa Mohan, June 4, 2019: The Times of India

From: Vishwa Mohan, June 4, 2019: The Times of India

From: Vishwa Mohan, June 4, 2019: The Times of India

Though such big landholders account for merely 0.6% of total farmers in India, their numbers in some states, such as Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Punjab, Karnataka, Haryana and Gujarat, are high.

Analysis of state-wise figures on landholders shows that 5.3% of total farmers in Punjab are large ones. Similarly, 4.7% of total farmers in Rajasthan and 2.5% in Haryana are big in terms of their landholdings. In other states, however, big landholders make up less than 1% of the total number of farmers due to fragmentation of holdings.

Large landholdings in Rajasthan may not be comparable with similar size of land in Punjab and Haryana in value terms (productivity) if one takes irrigation facilities and soil fertility into account, but the number of large farmers in the arid state presents an interesting picture. Rajasthan alone has 43% (3.6 lakh) out of the 8.3 lakh big farmers in India.

The top 12 states, including Rajasthan, collectively account for 93% of total big farmers in the country. On the other hand, there are 13 states/UTs, including Goa, Sikkim and Delhi, where number of large farmers is negligible. Other than UTs, most of such states are from the north-east. Though Nagaland and Arunachal Pradesh have big landholdings, they are mostly community land.

Among the remaining states, Telangana has 9,000 large farmers followed by Assam and Odisha (4,000 each), Bihar and Himachal Pradesh (3,000 each), Kerala (2,000), and Uttarakhand, West Bengal and J&K (1,000 each).

The figures are part of the Agriculture Census 2015-16.

Contract farming

2018: Centre releases a model act

Vishwa Mohan, May 23, 2018: The Times of India

From: Vishwa Mohan, May 23, 2018: The Times of India

Amid estimates of record production of agricultural and horticultural produce in 2018, the Centre released a model act on contract farming and asked states to adopt it to save farmers from price volatility.

The proposed model law - State/UT Agricultural Produce and Livestock Contract Farming and Services (Promotion & Facilitation) Act, 2018 - intends to integrate farmers with agro-industries and exporters for better price realisation by mitigating market and price risks.

Once adopted by states, it will formally facilitate entry of private players into the farm sector as it would induce competition and ensure assured and better price of farm produce to farmers through advance agreements. It can offer assured price to farmers and save them from a problem of plenty -- a situation where farmers opt for distress sale when bumper crops cause a glut in the market. “There is unanimity among the states to adopt the ‘model contract farming and services’ act in its true spirit so as to ensure assured market at pre-agreed prices,” said Union agriculture minister Radha Mohan Singh.

The proposed law was unveiled here in presence of agriculture marketing ministers from several states including Andhra Pradesh, Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Haryana, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh.

Economic issues

Input Costs And (Low) Returns

2017: Mismatch Between

Subodh Varma, Farmers' ire not about loans alone, June 10, 2017: The Times of India

Key Reason Behind Anger Is Mismatch Between Input Costs And Low Returns

The farmers' agitation in MP, and before that in Maharashtra, has pushed a simmering agrarian crisis into the spotlight.Earlier, the newly elected UP government announced a loan waver for small and marginal farmers, Maharashtra government said it was exploring the possibility. The Centre itself had announced that it would strive to double farmers' incomes by 2022. All these were raising expectations of farmers, especially after enjoying a good monsoon and record harvest in 2016-17, after two consecutive years of drought. Yet why are farmers the lifeline of India angry and resentful?

One of the key factors fuelling agrarian anger is that good year or bad year, they are unable to earn enough. There is always a mismatch between their cost of production and what they get in the mandis.

A quick comparison of cost of production and farm harvest prices as data collected by the agriculture ministry reveals the mismatch for 201415, the last year for which such information is available. In several states, for several widely cultivated produce like paddy and wheat, prices at which farmers are selling their harvest are actually lower than what they spent in cul tivating the crop.

In Madhya Pradesh, the epicenter of current agitation, paddy was fetching 15% less than cost of production while wheat was giving them just 2% profit. MP has emerged as a major player on the national scene exhibiting an agricultural growth rate of 9.7% between 2005-06 and 2014-15 compared to 3.6% for India as a whole. Share of agriculture in MP's gross state domestic product has increased from 25% to over 30% in this period. Area under vegetables and fruits has increased by 78% since 201011. According to a study done by Ashok Gulati and his colleagues at ICRIER, expanded irrigation, strong procurement system for wheat and bonus over its minimum support price and expansion of all-weather roads to connect farmers to markets have led to this boom in agriculture.Yet, after enjoying the boom for several years, the state's farmers have ended up in the same trap that has been haunting their brethren in other states.

The reason why farmers don't get suitable margins is because of their input costs -water, diesel, fertiliser, etc.

For cultivating wheat in MP, Rs 1,241.34 were spent on fertilisers per hectare in 2004-05 which has more than doubled to Rs 2,695.27 per hectare in 2014-15. Similarly , cost of seeds used in one hec tare increased from Rs 998 in 2004-05 to Rs 2,653 in 2014-15.Even cost of irrigation has jumped from Rs 1,961.50 to Rs 2,599.55 in this period. These and other costs like labour, agricultural machinery hiring charges, pesticides, rents, have all gone up while prices that farmers get have lagged behind. As recently reported, support prices may be higher than what farmers get but getting payments is so difficult that farmers often have to sell to traders at lower prices.

This dire situation is also causing mounting indebtedness of farmers with over half of agricultural households in debt as per an NSSO survey for 2012-13. MP was reported to have 46% debt ridden farmers.

Should farmers diversify to get more value for their crops? This would appear to be a way out except that even in those cases, farmers' margins plummet after some time.UP's potato farmers were getting a measly 5% profit, while in Punjab, cotton farmers have suffered enormous losses of as much as 20%.

2012>23

Atul Thakur, July 19, 2025: The Times of India

From: Atul Thakur, July 19, 2025: The Times of India

Indian farmers are hit by the double whammy of stagnant income and declining profit margins, according to an analysis of data compiled by the Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices (CACP). For nearly all major crops, the increase in agricultural income over the last decade has not kept pace with the rural inflation rate. The data also shows that the profit margins for most crops have declined.

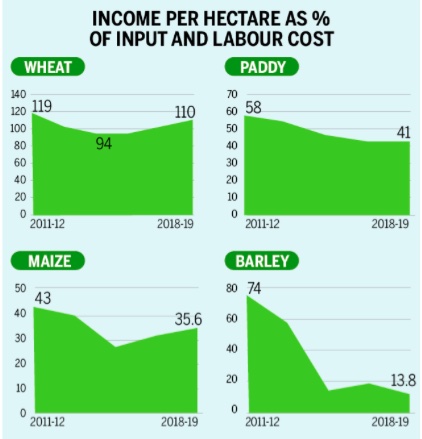

The analysis of ten major crops for both kharif and rabi seasons shows that, except for maize, groundnut and rapeseed/mustard, the increase in farm income has been less than the rural inflation rate during the same period. In 2013-14, the average input cost was Rs 25,179 per hectare for paddy while the value of family labour was assessed at Rs 8,452 per hectare. The value of the crop was Rs 53,242 per hectare, which meant a profit of Rs 19,611 per hectare. In 2023-24, this profit increased to Rs 30,216 per hectare. Although this was a 54% jump, consumer prices in rural areas increased by 65% between 2013-14 and 2023-24. The crop also saw a decline in profit margins. In 2013-14, the profit margin was 58% of the input and labour costs, which has now dropped to 49.3% of the cost. The input cost and family labour is taken as the total expense to calculate the profit margin since this spending is also part of the formula for Minimum Support Price (MSP).

Wheat, unlike paddy, is primarily a rabi (winter) crop, but a comparison of decadal growth in income and margins shows a similar pattern. The surplus over input cost and family labour was Rs 29,442 per hectare in 2012-13 and increased by 53% to Rs 45,179 in 2022-23. That’s lower than the 71% increase in rural consumer prices between 2012-13 and 2022-23. The profit margin too decreased from 123% in 2012-13 to 103% in 2022-23.

Sugarcane, another major crop, also saw a stagnation in net income. From Rs 96,451 per hectare in 2012-13, the profits increased to 1,21,668 in 2022-23. This 26% increase is lower than the increase in consumer price inflation. In 2012-13, the profit margin was 151%, which declined to 102% in 2022-23. Of the ten major crops (based on highest output) for which the comparison is done, only three have shown an increase in income higher than the inflation rate. These are maize (162%), rapeseed & mustard (85.7%) and groundnut (71.4%).

For the rest, the increase was lower than the inflation rate. It was between 50% and 60% for gram, between 20% and 30% for soyabean and cotton, and less than 20% for arhar (tur). Apart from stagnant incomes, the profit margins have declined for all of these crops except maize.

These per-hectare profits are roughly equal to the seasonal incomes for a vast majority of Indian farmers. The average land holding size in the Agriculture Census of 2015-16 was just under 1.1 hectares, but most farmers (68.5%) are marginal farmers, which means they own less than 1 hectare of land (averaging at 0.38 hectare). This means that seasonal income for them will be even lower.

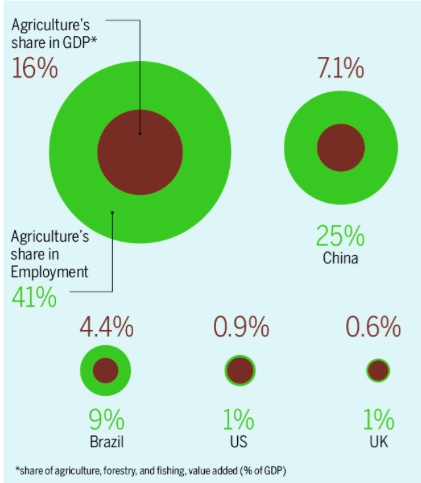

Experts have pointed out that the stagnation as well as lower agricultural income is due to the extent of mismatch between the share of agriculture in GDP and in employment. Despite contributing only 16% of GDP, agriculture employs more than 40% of India’s workforce. In advanced economies like the US, its share in GDP and employment is 0.9% and 2%, respectively. Even in a developing economy like China, agriculture’s contribution to GDP is 6.8% while it employs 22% of the workforce.

Farmers’ earnings

2008-16: How they are eaten away

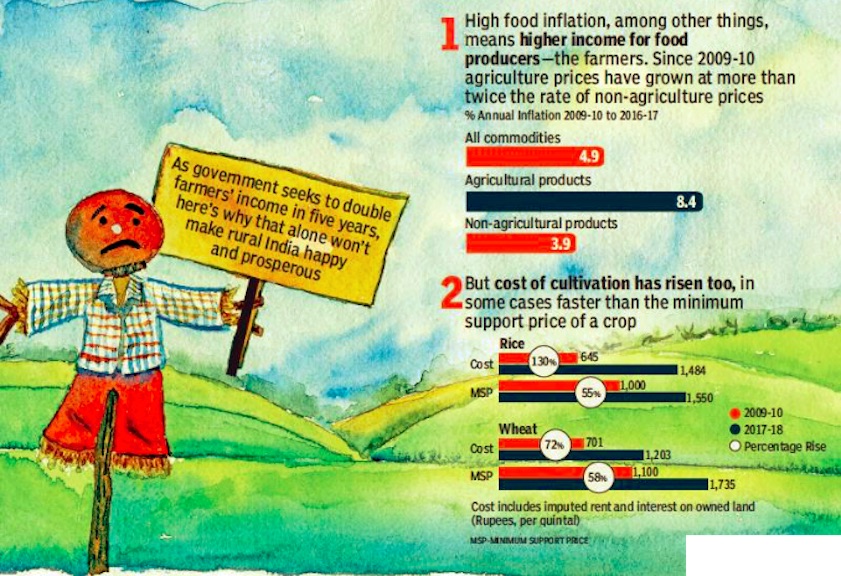

From: December 15, 2018: The Times of India

See graphic:

2008-16- How farmers’ earnings are eaten away

Productivity, returns, income issues

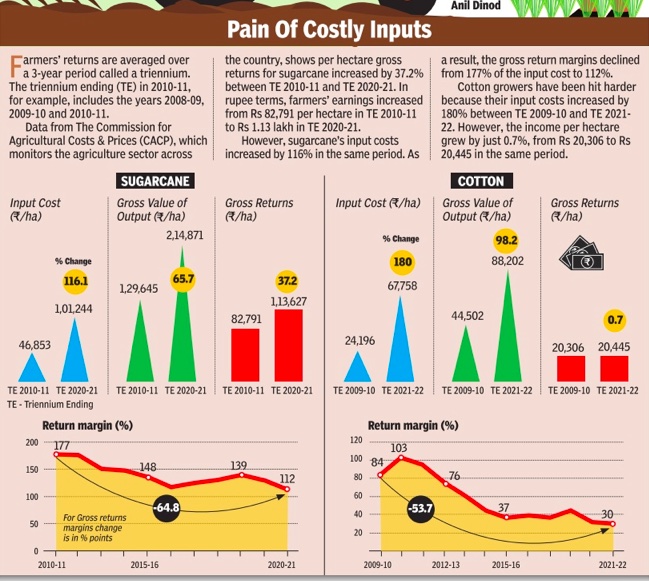

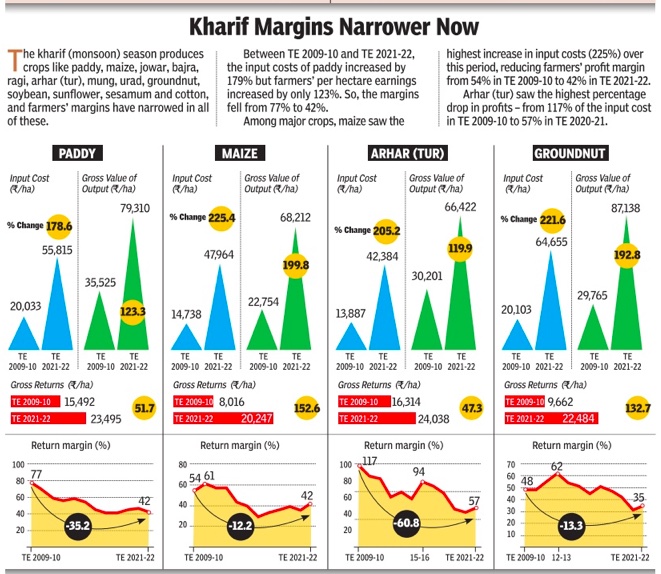

2020

Atul Thakur, December 10, 2020: The Times of India

Graphics: Nirmal Sharma

From: Atul Thakur, December 10, 2020: The Times of India

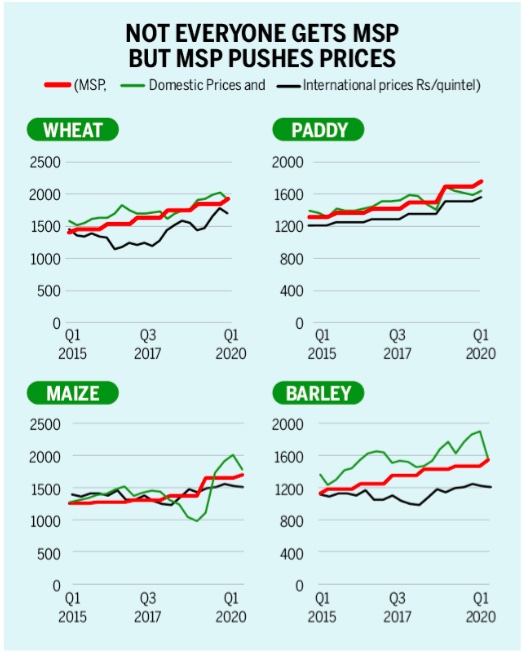

The impact of MSP on domestic Indian prices of foodgrains;