Global capability centres: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Benefits to the Indian economy

Till 2024, early

The unanticipated but phenomenal rise of Global Capability Centres (GCCs) of multinationals has been India’s greatest economic achievement in 2014-2024. These have made India a global hub for brainpower with no hoopla but to stunning effect.

According to a recent study by Wizmatic, a Pune-based consultant, GCCs now employ 3.2 million Indians, mostly engineers and scientists. They are estimated to generate a total revenue of $121 billion, of which $102 billion represents export earnings. That makes GCCs one of the biggest sectors in India, as well as saviours of the balance of payments.

In 2023-24, Indian exports of goods were $437 billion, and the trade gap in goods was a whopping $240 billion. But this was closed substantially by the trade surplus in services (to which GCCs contribute) of $162 billion. It saved our bacon.

Yet, paradoxically, this owes very little to government policies. It is an outcome of globalisation, of international forces that have driven technical jobs across the world to where the brains are. The West does not produce remotely enough STEM (science, technology, engineering, mathematics) graduates to meet its needs. Apart from China, India is the only country in the world producing an estimated 2.3 million STEM graduates per year, of whom half a million are engineers. Once of spotty quality, MNC confidence in them has risen sharply.

Initially, GCCs were called offshore captives of MNCs. At that time, they performed simple tasks like call centre operations and back-office work. As India’s skills developed, GCCs moved up the value chain into business process operations and software for their parent companies. Now, they have moved up further to become global MNC hubs for R&D, design, and artificial intelligence.

They constitute a financial black box because they have no separate balance sheets. MNCs often want to downplay their Indian operations for fear of being accused of exporting jobs. IBM, for instance, stopped giving a country-wise break up of its employees when its India numbers looked embarrassingly high. Accenture, the world’s top consultancy company, said a few years ago that 3 lakh of its 7 lakh worldwide workforce was in India, a stunning ratio.

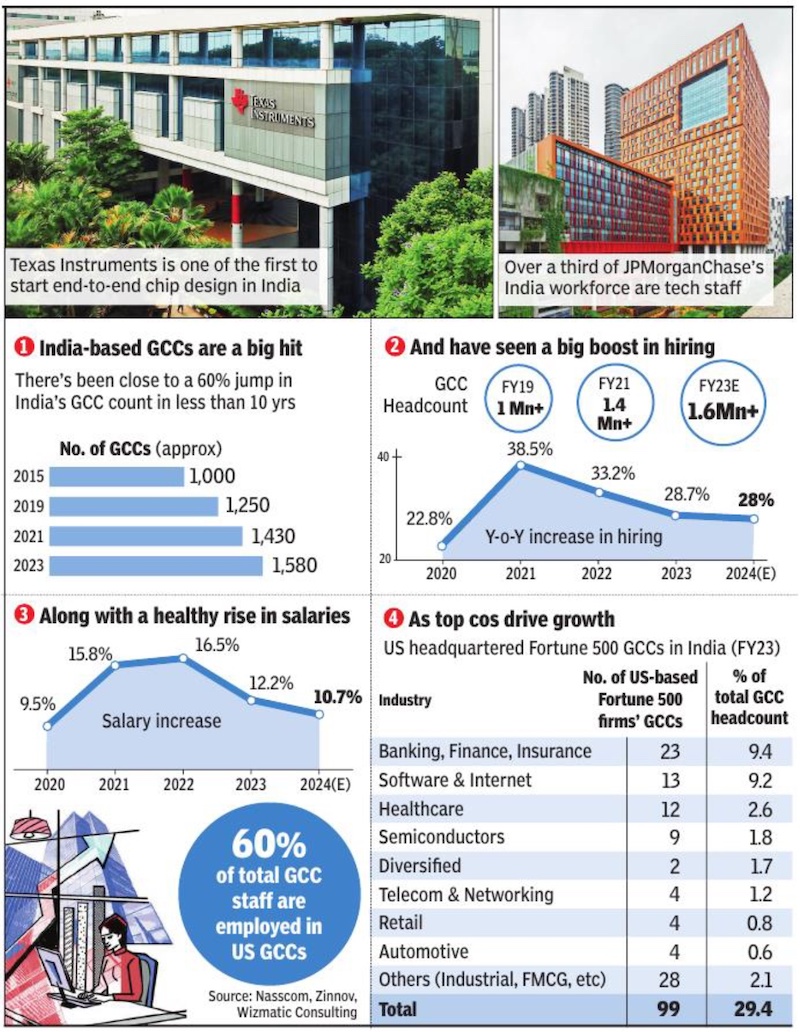

The first revelation of the meteoric rise of GCCs came in a 2021 Nasscom-Deloitte report. It said that between 2015 and 2020, GCC employment rose 75% to 1.3 million, and their number rose to more than 1,400. GCC revenues increased to $33.8 billion.

Moreover, GCCs provided many indirect benefits through maintenance, transport, suppliers and other linkages. Nasscom-Deloitte estimated that the gross output of all taken together was $99-103 billion in 2019-20, employment was 5.2 to 5.5 million, and taxes paid were $4-5 billion. Top engineering MNCs now depend on India for brainpower. The report estimated at the time that no less than 42% of GCC staff were in engineering R&D. General Electric, Volkswagen, and Mercedes Benz were all using India for engineering R&D.

But engineering is now only a minor part of the story. The MNC list has expanded to cover global retailers like Target and Tesco. Global pharma companies are notoriously worried about patents leaking out and have been slow to come in, but Roche is here.

From just in-house software, many GCCs went into producing Software as a Service (SaaS), a major revenue generator. But the most explosive growth has now been in AI. All top companies are now using India as a base for AI design and development.

The Deloitte Technology Trends 2024 report highlights the growth and global dominance of India’s GCCs, predicting that it will surpass $100 billion by 2030, fuelled by the emergence of approximately 2,500 more GCCs employing over 4.5m.

Employment provided

2024-25

March 3, 2025: The Times of India

India’s tech sector added 1.2 lakh people to its workforce in 2024-25, with global capability centres (GCCs) accounting for over 1 lakh of these roles, report Veena Mani & Shilpa Phadnis.

TOI earlier reported how this would be the second consecutive year when GCCs would surpass IT firms in net hiring. The scenario reflects a period when major IT companies are experiencing single-digit growth rates and workforce reduction, while GCCs contributed significantly to employment growth in the previous year.

Locations preferred

Hyderabad/ 2019-2024

Swati Bharadwaj, May 29, 2024: The Times of India

While Bengaluru continues to be India’s hottest GCC hub, accounting for about a third of the total, it’s Hyderabad that has seen the biggest jump in the share of GCCs. In 2019, when India was home to around 1,250 GCCs, Hyderabad had a 13% share at around 160 GCCs, while today, when the total number of GCCs has grown to over 1,600, the city houses around 19% or 304 GCCs, as per data provided by ANSR Research.

Hyderabad’s better infrastructure and lower costs compared to Bengaluru, a proactive government, and MNCs’ Bengaluru+1 strategy is benefiting the city. All of the five biggest global tech companies – Microsoft, Google, Apple, Meta and Amazon – have large centres in Hyderabad. As do big pharma like Novartis, Bristol Myers Squibb and Sanofi, healthcare and medtech players such as Providence and Medtronic, BFSI giants like Goldman Sachs, StateStreet, S&P and London Stock Exchange Group, semiconductor biggies like Micron, AMD and Qualcomm, and automotive giants like Stellantis and ZF.

Hyderabad is estimated to have added around 40 GCCs in 2023 and is on track to add a similar number in 2024. Real estate consultancy Knight Frank’s Q12024 report estimates that Hyderabad accounted for 39% of the total 5 million sqft of GCCoriented transactions across the top eight markets in the country.

“Hyderabad offers more affordable and cost-efficient real estate options than other major cities, allowing GCCs to optimise their operational expenses,” points out Anshuman Magazine, chairman & CEO – India, SE Asia, ME & Africa of property consultancy CBRE.

He says the Telangana government has also implemented favourable policies to attract and support businesses, including streamlining of real estate approval processes and incentives for setting up operations.

Telangana’s IT minister Duddila Sridhar Babu says Hyderabad’s biggest asset in the GCC race is the availability of a healthy pool of skilled talent along with the fact that it is an affordable city that boasts of world class amenities and infrastructure that has been built over the past two to three decades.

Of the over 1.6 million talent employed by GCCs in India currently, Hyderabad accounts for around 3.1 lakh (18%). In 2019, when the GCC talent pool in India was around 1 million, Hyderabad accounted for about 1.2 lakh or 12%. These talent pool is poised to go up to nearly 3.5 lakh by 2025, says ANSR Research. The city has a total IT talent pool of around 9-10 lakh.

Gaurav Gupta, partner & GCC industry leader at Deloitte India, says what Hyderabad also has going for it is the fact that it has evolved from the talent perspective. “Today close to 17% of the country’s digital and tech talent sits out of Hyderabad, roughly 10% of India’s finance and accounts related talent and 13% of business operations talent is based in this city,” Gupta points out.

Midmarket GCCs

2024-25: 27 per cent growth

Swati Bharadwaj & Shilpa Phadnis TNN, April 26, 2025: The Times of India

From: Swati Bharadwaj & Shilpa Phadnis TNN, April 26, 2025: The Times of India

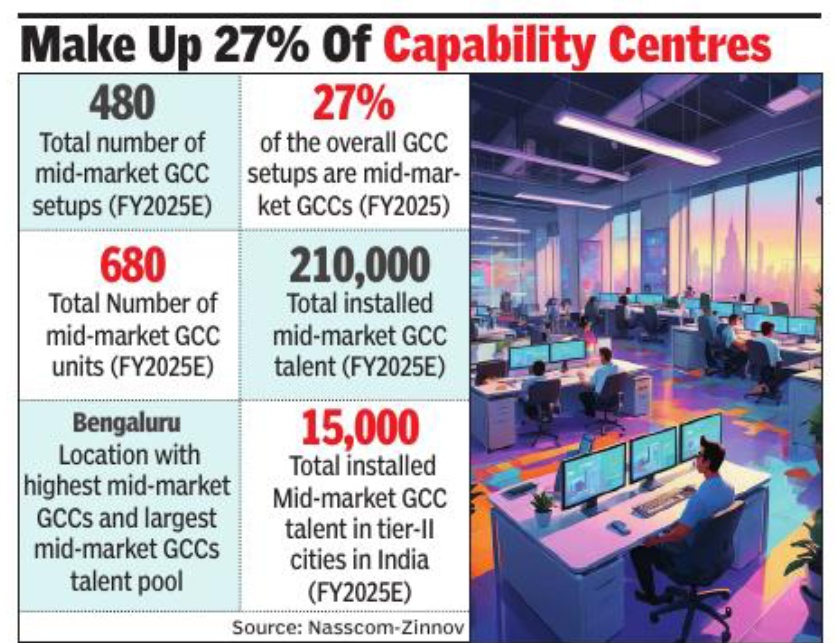

Hyderabad : India’s midmarket GCCs (global capability centres) are experiencing a surge, outshining their peers by unlocking new opportunities. This growth is creating a flywheel effect, allowing them to leverage a diverse talent pool. India has over 480 midmarket GCCs, with 2.1 lakh employees, as shown in a Nasscom-Zinnov report.

Mid-market GCCs are capability centres set up by midsized firms with annual revenue ranging from $100 million to $1 billion. They represent 27% of all GCCs and 22% of total units in the country. In the last five years, more than 110 new facilities were set up, representing approximately 35% of all new GCC units in India within this period.

About 60% of end-to-end platform ownership in enterprise portfolios is driven from India by mid-market GCCs.

Significant work is being done across AI/ML, cybersecurity, cloud, and data science. India hosts 47% of global product management talent and 25% of the deeptech workforce for mid-market GCCs.

Pari Natarajan, CEO and co-founder of global management company Zinnov, said that in mid-market companies, private equity ownership plays a significant role. These private equity firms implement structured value creation strategies, with India-based GCCs being a crucial component. “When such centres don’t exist, establishing them becomes a strategic board-level directive. For mid-market firms without private equity backing, the push towards India centres comes from board members who serve as operational leaders,” he said. North American firms, the report said, show a higher propensity to globalise, and India becomes an ideal destination given the learning agility and depth in the talent. The key destinations for mid-market GCCs continue to be Bengaluru, Hyderabad, NCR, and Chennai, which collectively host 74% of new GCC establishments. Notably, Hyderabad has evolved into a significant talent hub for mid-market GCCs during the past five years, accounting for 25% of the workforce expansion.

Mid-market GCCs focus on delivering high-value, specialised services while maintaining a leaner operational model compared to larger GCCs. Midmarket GCCs promote talent to site leadership 20% faster, enabled by leaner structures, early ownership, and direct visibility to global leaders. While mid-market GCCs often start as outposts like their larger peers, they tend to progress 1.2 times faster along the maturity curve.

Retail GCCs

2021

Avik Das1, January 13, 2021: The Times of India

From: Avik Das1, January 13, 2021: The Times of India

“We are not here for cost; it is about talent, capability and building a team to support various functions, including our online platform. Our Bengaluru office is the engine room for analytics,” says John Kenny, director of KAS Services, the India tech arm of Australia’s biggest discount department retailer, Kmart.

The company is among the numerous global retailers that are establishing technology centres in India, or expanding existing ones, to become more digital, so that they can take on the likes of Amazon and Alibaba. The Covid-19 pandemic has only underlined the urgency – the internet is where customers increasingly want to buy on, and without a digital backbone, supply chains can get badly disrupted.

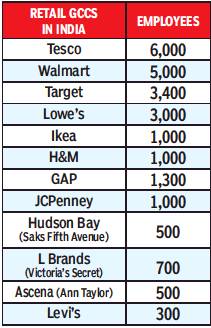

Bengaluru is home to the majority of these centres – Walmart, Target, Tesco, Lowe’s, JCPenney, Hudson Bay, L Brands, Ikea, Falabella. Not one has a single store here (an Ikea is coming up), but they are all developing new technology to make the shopping experience pleasant.

“The retail industry represents the highest levels when it comes to maturity of global capability centres (GCCs, as the captive centres are now called). They have become strategic to their parent companies,” says Lalit Ahuja, CEO of ANSR, a company that helps set up such centres in India. “Retail was slow to Amazon-ise, and now these retail centres are coming up to drive change and bring new technology and innovation,” he says.

India has nearly two decades of experience in retail tech. Target and Tesco came to Bengaluru in the early 2000s to consolidate back-office operations and make them more efficient with the use of IT. Flipkart’s emergence and Amazon’s entry, and their intense rivalry added to the retail tech talent pool. The new retail GCCs are benefitting from this talent. “The country now has extremely relevant talent – talent that understands all aspects of retail,” says Lalitha Indrakanti, head of global business operations for Sweden’s Ingka Group, which runs Ikea, and which recently established a global business operations cum digital centre in India.

Chilean retailer Falabella’s India centre has built the point-of-sale (PoS) system for its stores in seven Latin American countries, and integrated its indigenous e-wallet in the retail ecosystem. The centre also manages the e-commerce operations and digs into data to provide more personal experiences.

“Falabella has multiple retail formats, and a host of other businesses including financial payments, banking & insurance, driven by the goal to build an ecosystem for our customers. It requires a holistic technology transformation across the conglomerate. We knew it wouldn’t be possible to do that in Chile or anywhere in Latin America alone, so we chose India as a key location, given the talent pool,” Ashish Grover, MD of Falabella India, says.

The digital acceleration is taking place across ten key retail themes, consultancy firm Zinnov says. These include automated checkout, contactless payments, omnichannel inventory management, warehouse automation, stores as fulfilment centres for online orders, autonomous last-mile delivery, virtual trials, assisted shopping, social commerce, and move to marketplaces. It estimates that globally, the retail sector has invested in three years’ worth of digital transformation within six months, spurred by the pandemic.

Walmart’s engineers in India have helped build the tech stack for the US supply chain and have developed tech solutions for its Mexican e-commerce platform. They are reimagining in-store and online shopping experiences.

US home department chain Lowe’s centre in Bengaluru is involved in developing and pricing products. It has product management, engineering, data analytics and operations teams in India that help manage assortments at the stores, pricing, inventory and store design.

Kmart’s Kenny says one of the advantages of having a base in Bengaluru is the presence of other retailers, which facilitates sharing and learning unlike other places. “The team here works on high-end technology. We have built PoS solutions, we have built solutions that make teams more effective. We have a demand fulfillment team that allows us to forecast stock in store a lot more accurately,” he says.

Minneapolis-based Target started in India as a shared services centre. Today, the centre supports global strategy across technology, marketing, human resources, finance, merchandising, supply chain, analytics, and reporting. The company says the work involves creating highvalue tools and products to create a competitive advantage.

Retail GCCs, says KS Viswanathan, vice president of industry initiatives at Nasscom, are increasingly working on services like marketing, social media campaigns, designs for new shops and managing e-commerce operations and online customer experience. And are providing analytics and insights.

Salaries/ compensation

As in 2024

Shilpa Phadnis, May 29, 2024: The Times of India

GCCs have emerged as great paymasters, outshining their IT services peers. Around 100 Indian GCCs have top leaders netting nearly $1 million in annual compensation, including cash and stock rewards, says Lalit Ahuja, founder of consulting firm ANSR. These roles include India site leaders and SVPs who lead technology functions.

Other roles too have seen a good increase in salaries. ANSR’s research shows that the average salaries for those who have around seven years of experience in digital roles have increased by 33% to $45,000 (Rs 38 lakh) in 2024, from $33,000 (Rs 28 lakh) in 2021. On the other hand, the median remuneration of employees in an IT services company in India was around Rs 9 lakh ($11,000) in FY23, up from Rs 5 lakh ($7,400) in FY15 – a CAGR of 8% over the last eight years, in line with industry revenue growth, says a report by Goldman Sachs.

Consulting firm Zinnov estimates that GCCs gave increments of 12.6% last year, even as most major IT services com- panies deferred salary increments or gave it only to select few top performers. Those at junior levels in GCCs received on average 13.2% increments. Top performers, Zinnov says, received average increments of 20.2%.

An HSBC report highlights that GCCs’ cost per head is 30%-40% higher than that of Indian IT services providers, given that GCCs have traditionally hired laterally, and have far fewer freshers. GCCs also give higher salaries for the same level. However, as IT service providers have a significant offshore markup (pricing over costs), GCCs’ cost per head is 20-25% cheaper than the billing rate of service providers, says HSBC analysts Yogesh Aggarwal and Prateek Maheshwari.

An EY report says that the overall cost of a full-time employee in a GCC will increase from the current average levels of $29,100, to $37,760 by 2030. According to its research, the cost per employee has increased by 27% from the year 2019 to 2023. However, it is expected to increase by 30% from now until 2030.

12-20% more than IT companies: 2024

Swati Bharadwaj, August 27, 2024: The Times of India

Hyderabad : Global capability centres (GCCs) are not only rapidly making their presence felt across India’s tech landscape in terms of their expanding footprint, which is now spilling over beyond tier-1 cities to tier-2 centres, but also when it comes to heftier pay packages.

GCCs are offering 12-20% higher compensation compared to traditional IT products and services companies or even non-tech companies hiring for tech roles, the findings of a TeamLease Digital report show.

India has over 1,600 GCCs employing over 1.66 million professionals. This is poised to touch 1,900 GCCs with over two million professionals by 2025, focusing on GenAI, AI/ ML, Data Analytics, Cybersecurity, Cloud Computing, and RPA, the report said.

This is even as the Indian tech industry is projected to reach $350 billion by 2025 with significant investments in AI, ML, and blockchain, up from $254 billion in FY24, it said.

The report, which spans over 15,000 job roles, found that in the key functional areas such as software develop- ment and engineering, cybersecurity and network administration, data management and analytics, cloud solutions and enterprise applications management, project management and user experience as well as systems operations and technical support services, the compensation packages offered by GCCs across entry, mid and senior levels in top in-de- mand roles far outpace those offered by traditional IT and non-tech companies.

The report also points out that metro cities such as Bengaluru, Gurgaon, Hyderabad, Delhi, Mumbai, and Chennai offer the highest salaries for tech job roles. Tier-2 centres like Jaipur, Indore, and Coimbatore, which are the upcoming hubs for GCCs and data centres, are seeing a growth in demand for functions of Data Science, Product Management, and Data Engineering.

Krishna Vij, vice-president, TeamLease Digital, said GCCs, focused on advanced technologies such as Generative AI, AI/ML, Data Analytics, Cybersecurity, and Cloud Computing, are driving digital transformation and setting new standards in innovation.

“The compensation in these centres is notably higher—ranging from 12% to 20% more than traditional IT services—underscoring the premium on digital skills,” she said. “With 800 new GCCs anticipated in the next 5-6 years, this sector’s growth is not limited to major cities like Bengaluru and Hyderabad. There is a growing expansion into tier-2 cities,” Vij explained.

The status of GCCx in India

2022: India’s rise as GCC hub

SWAMINATHAN S ANKLESARIA AIYAR, India’s rise as GCC hub shows way forward

One form of globalisation is progressing rapidly without much recognition. This is the rise of Global Capability Centres (GCCs). Nasscom (National Association of Software and Service Companies) estimates that by 2021 more than 1,400 MNCs (multinational corporations) set up GCCs in India, employing 1. 3 million highly skilled people with a revenue of $36 billion. Nasscom projects that by 2025 India could have 2,000 GCCs employing 2 million people and generating $60 billion of revenue.

Many Indian start-ups have been created by former employees of the GCCs. Thus, skills nurtured by GCCs spill over into other sectors. This helped India create 100 unicorns (unlisted start-ups with an estimated market value of over one billion dollars).

The rise of GCCs has escaped attention because MNCs do not publish separate balance sheets for offshore operations, in India or anywhere else. Many MNCs have no interest in highlighting the growth of their GCCs because it might open them to accusations of exporting jobs to low-wage countries. Once, high-level skills were available only in advanced economies. Today MNCs cannot get enough skilled staff in their home countries and so search the world. They find India is a major source of talent.

Back in the 1990s, foreign companies began offshoring low-level work like call-centres and medical transcriptions to India and other developing countries. Next computer software and business processes were offshored on a large scale after 1998. Much offshored work went to Indian companies but an increasing amount was also done by captive centres of MNCs in India, an in-house form of offshoring. These centres have now risen in sophistication and technical excellence to become GCCs that are global hubs for design and R&D. Nasscom estimates that 42% of employees in GCCs are in engineering R&D.

Ironically, education in India is terrible overall. Schools and colleges produce millions of semi-literate students who are unemployable. Yet India also has some world-class educational institutions that are expanding in both the public and private sectors. MNC managers say that no other coun-try (save China) produces half a million engineering graduates of decent quality every year. Doing business in India can be tough, but fierce competition for talent obliges MNCs to come to India, in services if not manufacturing. Deloitte estimates that 45% of the world’s GCCs are in India. Accenture, the world’s biggest consultancy company, recently revealed that of its 700,000 employees worldwide, no less than 300,000 were in India. Goldman Sachs reportedly plans to expand its Indian GCC to 2,500 employees by 2023. IBM and CapGemini have over 100,000 employees in India.

Historically pharma MNCs were reluctant to expand in India for fear of losing their intellectual property rights to Indians who were seen as expert “copycats. ” Today Indian skills have gone well beyond mere copying and so MNCs are beefing up their R&D centres in India. AstraZeneca had a great collaboration with Serum Institute of India to produce anti-Covid vaccines that saved millions of lives globally. AstraZeneca now plans a GCC in India.

The status in 2023

June 15, 2023: The Times of India

On the eastern side of Bengaluru, sits a campus housing three cube-like glass buildings. Each is 10 storeys high, with facades glistening in the sun.

These are the offices of Goldman Sachs group, home to about 8,000 workers, the bank’s largest venue outside New York. When Goldman set up in the city in 2004, it had roughly 300 people mainly providing information technology and other support. Now, its workers are quants and software engineers, building systems for everything from making trades to managing risk.

Across India, the offices set up by multinationals to provide cheap operational support are taking on more sophisticated roles. While the shift has been underway for years, recent economic data highlights a rapid service-sector expansion that many attribute to the offices known as global capability centres (GCCs).

These now account for more than 1% of India’s gross domestic product (GDP). But the boom also creates challenges, both for the companies and the cities that host them. Finding qualified employees is becoming more difficult, pushing salaries up, while offshoring may become politically sensitive again in the US presidential race.

The pull of India

“Over the last 30 years, while China specialised in becoming the world’s factory, India specialised in becoming the world’s back office,” said Duvvuri Subbarao, a former governor of the Reserve Bank of India. “Over the years, India moved up the value chain,” he said. But it can’t “take its comparative advantage for granted”. India has roughly 1,600 of the centres, more than 40% of the number worldwide, according to Nasscom, a trade body for the technology industry.

Dotted around Bengaluru are the offices of luxury retailer Saks Fifth Avenue, aircraft-engine maker Rolls Royce, US bank Wells Fargo and Japanese e-commerce firm Rakuten. Some 66 global companies set up their first GCC in India in 2022. Even the lingerie brand Victoria’s Secret has a Bengaluru GCC.

The offices generated about $46bn in combined revenue in the fiscal year ended March, more than the output of Nepal.

The qualities that turned India into the world’s back office starting decades ago are propelling GCCs’ metamorphosis: A vast pool of young people, an education system that emphasises science and technology, and the lower staffing costs that made India attractive in the first place.

Add an unforeseen catalyst: The pandemic, which convinced decision-makers jobs can be done anywhere, including far-flung shores.

“India’s story starts with its demographics and its talent,” said Gunjan Samtani, the country head of Goldman Sachs Services, the entity that operates the bank’s GCCs in India. A software engineer by trade, he still codes from time to time. “What brought us here even two decades back was our ability to get access to technology and talent.”

More than a back office

Last year, a mysterious surge appeared in the country’s economic data. Services exports rose to a record for December, leading economists to speculate why. The trend continued. They climbed to about $323bn in the fiscal year ended March, up 27% from the year before. Analysts reached the same conclusion: It was the GCCs.

GCCs have been driving the exuberance in services exports, Pranjul Bhandari, HSBC Holdings' chief economist for India and Indonesia, and colleagues wrote in a report in March, calling it a “meaningful” shift in India’s economy.

Its significance went beyond the boost in output. The increase helped narrow the country’s current-account deficit, which in turn could support a rupee that’s been depreciating for years.

It was an important moment for a business that’s been in the making for decades. Global capability centres trace their roots to the 1980s, when Texas Instruments established a facility in Bengaluru.

India took off as an outsourcing hub in the 1990s, when airlines, technology companies and firms including American Express and General Electric set up centres in the country. The facilities took over business processes including accounting, payroll and customer support, with lower labour expenses allowing companies to cut costs.

The multinationals soon saw they could use their India offices for more than back-office functions. Today, they often handle core operations, such as inventory management or purchasing, while also using AI and other advanced technologies to improve how businesses run.

Retailer Target is working on new systems for order collection and shipping. At Goldman, engineers have helped develop a trading system called Atlas for quant clients with latency in microseconds. They’ve also expanded a commodities platform called Janus, which provides data analytics.

“The conversation has changed completely,” said Sindhu Gangadharan, senior vice-president and managing director of SAP Labs India. Cost is “a beautiful advantage that we have, but that’s not the conversation starter like it was 20 years back”.

SAP Labs India is now responsible for almost 40% of software firm SAP’s global research and development and a quarter of its patents annually, Gangadharan said.

Goldman’s GCCs carry out more than 120 global functions across engineering and business operations. JPMorgan Chase employs more than 50,000 people at GCCs in five locations across India, in areas including quant research, data science and cloud computing.

GCCs “are now following a very different path”, said Lalit Ahuja, the founder and chief executive officer of ANSR, a consultancy that has helped clients establish more than 100 of the centres in India. He says he sets up two every month and has never been busier.

The pandemic changed everything by making remote work more acceptable, Ahuja said. The industry came of age in the last few years, he said.

Huge talent pool

One of India’s biggest attractions is its supply of workers. In April, it overtook China as the world’s most populous country. It’s now home to almost a fifth of humanity, and more than half its population is under 30, with a median age of 28. That compares to 38 in both the US and China.

In a nation obsessed with education, many parents want their children to take subjects that will help them get good jobs and careers. Some 34% of students study science, technology, engineering or mathematics at university, the highest among major economies, according to Unesco Institute for Statistics data.

And these days, India’s thriving startup scene is also a boon for companies setting up GCCs and seeking people to hire. India has about 90,000 startups, the third-biggest number of any country in the world.

But the surge in GCCs is making it harder to find employees and creating a need to pay them more. Companies are forming ties with academia to develop hiring pipelines.

SAP Labs India has a partnership with engineering school Birla Institute Of Technology and Science, Pilani. Goldman runs an annual contest called GS Quantify for students to find solutions to real-world financial problems. Samtani says the bank gets job applications from more than 1,100 campuses in 20 states.

“The war for talent definitely exists,” SAP Labs India’s Gangadharan said.

Even before competition for staff intensified, companies needed to spend much time training new hires, according to Dileep Mangsuli, executive director and head of the development centre at Siemens Healthineers, a medical-technology company involved in imaging and diagnostics, which now does half its software and digital-services research and development (R&D) in India. Good jobs exist in the country, but the booming education industry often doesn’t adequately prepare people to do them.

The employability of new graduates “is still a challenge”, he said. “Till they’re trained and retrained and many times trained, they don’t become employable.”

As GCCs use more advanced technologies, they’re also finding it harder to find staff. An example is artificial intelligence. India has about 416,000 AI workers, far short of the more than 1mn it will need by 2026, according to Nasscom.

Not an easy road ahead

Making the most of India’s demographic advantages “will require significant investments and government attention”, said Partha Iyengar, the country leader for research at Gartner in India. Only 30-40% of graduates in India are employable, he estimates. “Not enough attention is being given to this, given the massive scale of intervention required”, he said. “If that is not done on a war footing, the demographic dividend can very easily and quickly turn into a demographic disaster.”

The boom is also adding to challenges for India’s cities, especially Bengaluru.

Home to about 30% of the country’s GCCs, India’s tech capital is constantly congested. As work continues on expanding the metro system, large stretches of the city are dug up, resulting in long traffic jams. Last year, torrential rain caused floods across key roads, forcing chief executive officers to ride to work on tractors.

Multinationals are setting up in other places. Hyderabad is emerging as a popular location. Goldman opened its second India GCC there in 2021 with a focus on consumer-banking services and business analytics. Pune is another favoured destination, as are some areas near New Delhi.

Another risk is that Donald Trump will revive his campaign against offshoring of jobs as he runs for president again in 2024. Data sovereignty — another argument for keeping jobs at home — could also become an issue.

Still, Nasscom estimates India will have at least 1,900 GCCs by 2025, and annual revenue from the industry will increase to as much as $60bn. “India can overcome the geopolitical challenges because such a large talent pool is not available elsewhere,” said K S Viswanathan, the trade body’s vice-president of industry initiatives.

At Goldman, Samtani shares the optimism. He points out the bank had one managing director in the city in 2004. Today, in Bengaluru and Hyderabad, 58 people have reached the coveted rank. “If India is not part of the talent story for any firm globally, they’re missing something,” he said.

The Top GCCs in India /2023

From: May 29, 2024: The Times of India

See graphic:

The Top GCCs in India in 2023, industry-wise

2020-24: number of GCCs, employment created, salaries, growth

Shilpa Phadnis, August 17, 2024: The Times of India

From: Shilpa Phadnis, August 17, 2024: The Times of India

Once they were considered back offices catering to Fortune 500 companies. But that was then. Global Capability Centres (GCCs) have since emerged from the shadows, expanding their sphere of influence within the Indian tech landscape. They have evolved into tech powerhouses, seamlessly integrating with their parent enterprises and becoming strategic assets providing access to digital talent at scale. This has reshaped the perception of GCCs within the Indian tech industry. From peripheral centres, GCCs have emerged as global hubs of strategic operations.

Nearly 40 years after India’s GCC poster boy, Texas Instruments, made Bengaluru its home for R&D operations, Indian GCCs have created a compelling story for global companies to acknowledge India’s enviable tech talent pool. This has, a) created more tech jobs in India; and b) solidified India’s position as a hub for advanced technological development.

6 Lakh New Jobs In 5 Years

Just consider these numbers: India now has about 1,600 GCCs. This is estimated to go up to 1,900 by next year. According to a Nasscom-KPMG report, their combined market size now is $60 billion. In 2014-15, it was $19.6 billion, which more than doubled to $46 billion in 2022-23, a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 11.4%. GCCs added over 6 lakh new jobs between 2018-19 and 2023-24, taking the total job count to over 16 lakh or 1.6 million. If this sounds good, here’s some better news for the sector. The latest Economic Survey was upbeat about the future of GCCs. By 2030, the Survey projects, GCCs will contribute a total revenue of $121 billion — roughly 3.5% of India’s current GDP. Of this, $102 billion will come from exports.

Take JPMorganChase, for instance. Its headcount in India grew to over 55,000 from 34,000 in 2018. Deepak Mangla, CEO, corporate centres, India, and Philippines at JPMorganChase, in a recent interaction with TOI, said its India operations are a microcosm of all lines of businesses and functions, not just technology. “We consider ourselves a technology-driven bank. I think we have a very good strategy for distributed talent across the globe. We have more than 60,000 technologists at the firm and approximately one-third of them are in India. Our India corporate centres specifically employ 55,000 people, of which there are approximately 20,000 people in technology.”

Gunjan Samtani, global COO of engineering at Goldman Sachs and country head of Goldman Sachs Services India, said over 120 global functions across business and engineering are carried out from its Indian GCCs in Bengaluru and Hyderabad, which employ 8,500 people. “Over the last two decades, functions performed from India have evolved from end-of-day support for trading platforms and exchange connectivity to algo trading platform support, data analytics, and client reporting. Today, the India GCC is a centre of excellence with thought leadership for several equities engineering functions,” he said.

Innovation Hubs

GCCs in India have emerged as a playbook for innovation hubs. Texas Instruments (TI) India, for instance, is one of the first players to enable endto-end chip design in the country. “TI engineers play a significant role in the entire chip design process, from concept to design, product engineering, testing and validating, and system software... Some of the best teams in the industry for product development exist here in TI India,” said Santhosh Kumar, TI president and managing director.

Goldman Sachs’ India centre has developed Atlas, a low-latency trading platform that hosts a comprehensive suite of trading strategies to help clients achieve their trading objectives, perform histor- ical analyses, build quantitative models with real-time market information, and trade execution. “This platform helped trim microseconds in the execution of trades for our (low-latency trading) clients. The latency reduction from this platform helped us engage existing and newer hedge funds and quant clients,” Samtani said.

Recently, GE Aerospace CEO Larry Culp told TOI that the company’s 1,200 engineers at the John F Welch Technology Centre in Bengaluru are involved in cutting-edge work on the future of aviation — including the Leap engine for narrow-body aircraft, the GEnx in the wide-body space, and the next-generation Rise platform for the narrow-body market. The company also announced an investment of over Rs 240 crore to expand and upgrade its manufacturing facility in Pune. The factory already produces components that are supplied to GE’s global factories, where they are used to assemble engines like the G90, GEnx, GE9X, the world’s most powerful commercial jet engine, and the Leap engines by CFM, a GE and Safran joint venture.

Moving Up The Value Chain

Sangeeta Gupta, senior VP and chief strategy officer at Nasscom, said India will continue to be central to the growth of GCCs, making significant impacts across economic, human capital, innovation, social, and environmen- tal dimensions. “Talent will be a key driver of this growth, with both new and established centres expanding their capacities. There’s a notable shift towards incorporating corporate functions, analytics, and AI, with tasks increasingly focusing on corporate functions, product management, decision support, and embedded systems capabilities.”

Gupta added: “GCCs are increasingly important to their parent enterprises, focusing on moving up the value chain, creating opportunities for future leadership, and enhancing their overall impact.”

Ramkumar Ramamoorthy, partner in tech growth advisory firm Catalincs, said, “With several hundred GCCs gaining critical size, I expect their employment numbers to accelerate from here. I will not be surprised if the GCC headcount crosses 4 million in India in the next five years. The oth- er big impact that today’s GCCs are making is the transfer of technology through R&D, and knowhow in newer areas such as product development and management, AI, cyber engineering, edge computing, synthetic biology, etc. The fact that ISB, IIMs and IITs today offer advanced programmes in product management is a case in point.”

As the boundaries blur between tech and traditional industries, GCCs are becoming talent hotspots in newer areas like full-stack development, AI, IoT, embedded systems, and automation, reshaping global markets. “Established GCCs are nurturing advanced skills beyond pure technology, including product management and architecture, where they are building deep domain expertise. This shift enables them to deliver higher-value work and gain a more comprehensive understanding of business contexts,” said Pari Natarajan, CEO of global management consultancy Zinnov. Its research showed that the number of global roles in GCCs in India is projected to grow from a mere 115 in 2015 to 30,000 by 2030.

Better Salaries

Lalit Ahuja, founder of Bengaluru and US-based ANSR, which has set up over 120 GCCs, said GCCs have emerged as good paymasters, outshining their IT services peers in several roles across firms. Around 100 Indian GCCs have top leaders netting nearly $1 million in annual compensation, which includes cash and stock rewards, Ahuja added. These roles include India-based site leaders and senior VPs who lead technology functions.

Arindam Sen, EY India Global Business Services & Operations partner, said roles like CIO, CTO, chief financial officer, chief procurement officer will be increasingly based out of India. “People from these centres are growing within the organisation and assuming these roles. Either the role itself sits here or people selected from these centres as part of their talent strategy are eventually taking up those roles.”

As in 2024 April

Sujit John & Shilpa Phadnis, TNN, May 29, 2024: The Times of India

From: Sujit John & Shilpa Phadnis, TNN, May 29, 2024: The Times of India

WILL THE NEXT SATYA NADELLA SIT OUT OF INDIA?

American firms have more employees in India than in any other foreign country

TOI, and Times Techies in particular, have been tracking the meteoric rise of GCCs for years now.

Late 2023 , we wrote, based on consultancy Zinnov’s estimates, that more than 5,000 global leaders of MNCs are sitting out of India GCCs. These are not just tech leaders, but also operations’ leaders, including, significantly, the chief customer officer of US data protection and management company Commvault (by that yardstick, the possibility of a Nadella sitting out of India isn’t far-fetched). Zinnov estimates this number will rise to 30,000 by 2030. In February, we wrote, based on consultancy Wizmatic’s estimates, that the GCC revenue figure of $46 billion that Nasscom put out for 2022-23 could be a gross underestimate, that it could actually be more than $100 billion. That’s more than 3% of India’s GDP.

GAINING GLOBAL ATTENTION

Today, the India GCC phenomenon has caught international imagination. The Economist magazine has just written articles on it, pointing out also that American firms have 1.5 million staff in India, more than in any other foreign country. They note the substantial contribution of GCCs to India’s GDP, and more particularly the country’s services exports. They point out that GCCs could do to India what FDI into China’s manufacturing did for that country. And the value brought in could be even more significant, considering what’s moving into India is the knowledge base of the world.

Ankur Mittal, SVP of technology & MD for India at Lowe’s, the $86-billion US retailer specialising in home improvement and which has a 5,000-strong GCC in India, says US companies have realised that talent availability in India is “far superior to most other locations

EASIER TO TRANSFORM Ahuja says it’s easy to build a large-scale team in India that can be trusted to drive business outcomes with certainty and predictability. “A company like Best Buy that is just coming into India can hire from Walmart, Target, Lowe’s, Amazon, and even Microsoft and Google. They can hire teams within weeks that can build enterprise-grade capabilities and help in digital transformation. A Cigna comes to India and can do 10,000 people in three years,” he says.

UNDER-ONE-ROOF ADVANTAGE

Another huge India advantage is the possibility of housing di verse talent under one roof, which almost every MNC today is consciously putting in place. Mittal notes the presence of technology, design, product management, data science, AI and even business talent like marketing and merchandising in Lowe’s Bengaluru facility.

CUTTING-EDGE WORK

Over 120 global functions across business and engineering are carried out from Goldman Sachs’s India GCCs that have 8,500 employees. Over the last two decades, functions performed from India have evolved from end-of-day support for trading platforms and exchange connectivity, to algo trading platform support, data analytics, and client reporting.

A major project that the India centre led is Atlas, a low-latency trading platform that hosts a suite of trading strategies to help clients achieve their trading objectives, perform historical analyses, build quantitative models with real-time market information and trade execution. This platform helped trim microseconds in execution of trades for Goldman Sachs’ clients. “This latency reduction helped us engage existing and newer hedge funds and quant clients,” Samtani says.

JPMorgan Chase, the world’s largest bank, has some 55,000 people in its India GCCs. Deepak Mangla, CEO of corporate centres for India & Philippines at the bank, says the India GCC is a microcosm of practically all lines of businesses and functions, not just technology. “We manage operations for the bank, we engage extensively in risk management, we perform significant work for finance and HR controls,” he says.

Among several path-breaking work done at Lowe’s India is what’s called LORMN (Lowe’s One Roof Media Network). It was conceptualised in India and is among the fastest growing retail ad networks in the US. It allows vendors to put ads on Lowe’s website and other sites.

2020- 2024: rapid growth

Shilpa Phadnis March 24, 2025: The Times of India

From: Shilpa Phadnis March 24, 2025: The Times of India

See graphic:

Indian GCCs with more than $1 billion revenue, 2020- 2024

Bengaluru : India’s GCC (global capability centre) story is getting bigger and bolder. There were 24 GCCs surpassing the $1 billion export revenue mark in financial year 2023-24, up from 19 in the previous year, according to research by Pune-based consultancy Wizmatic. These 24 collectively generated exports exceeding $43.6 billion.

GCCs are the technology and operations arms of MNCs in India, and they are increasingly embedding themselves into the core of Fortune 500 enterprises with their innovations and strategic influence.

Wizmatic founder Sandeep Panat says India is beginning to see the emergence of giga capability centres.

The number of billion-dollar GCCs has doubled from 12 to 24 in the five years upto FY24. Various consulting firms have projected that the number of GCCs will grow in the coming years, creating additional jobs. According to a PwC report, by 2028, the country is poised to have 2,100 GCCs, with the market size of the centres touching $90 billion. A Nasscom-KPMG report estimates India will have 1,900 GCCs, with $60 billion in revenue, by the end of this year. While some do not include the Indian operations of IT services companies like Accenture and Capgemini among GCCs, Wizmatic inclu- des them on the grounds that their operational models and local legal structure in India are no different from that of other MNCs with GCCs in India. The revenue model is based on services rendered to their parent companies and global affiliates, with a predefined markup regulated by transfer pricing norms.

“The revenue gets credited where the clients are, like the US or Europe, not India. For these firms, income is tied to where clients are located, not where the work is executed. In principle, a GCC doesn’t generate revenue independently, it enables revenue for the parent entity ,” Panat says.

As they scale, their ability to reinvest in R&D, digital capabilities, and strategic initiatives will grow. Transfer pricing policies dictate the margins GCCs can operate on, influencing their financial structuring and growth strategies. “While most GCCs operate on a cost-plus model, their financial success is determined by their ability to increase value addition. Unlike IT service providers that maintain a bench workforce, GCCs function as specialised entities with dedicated service lines for their global parent organisations,” says Panat.

Phil Fersht, CEO of HfS Research, said in terms of contributing to the top-line growth of their parent organisations, the jury is still out on whether GCCs can deliver more than efficiency. Currently, they are more of an efficiency play under the banner of “innovation”. “However, the future hope is they will start to contribute to top-line growth as they grapple with AI opportunities and become more integrated with the leadership of their parent organisations. The simple fact that GCCs offer the chance for Indian talent to get closer to global enterprises and have a more direct impact on their clients is making the GCC career option far more attractive than many of these “back office” service provider roles,” he said.

Lalit Ahuja, founder of ANSR, said GCCs have always hosted leadership roles and executed functions that directly impact topline of companies. “This includes ownership of revenue driver digital products and platforms such as online banking and e-comm. With scaling of GCCs, the ‘billion dollar’ impact club continues to grow at a rapid pace.”

Women in GCCs

2022-23

May 1, 2024: The Times of India

From: May 1, 2024: The Times of India

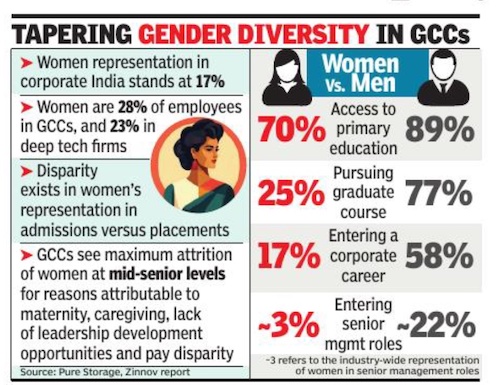

Bengaluru : Indian global capability centres (GCCs) have made significant strides in gender diversity, with nearly five lakh women currently employed in the sector. This represents 28% of the total 16 lakh employees working in GCCs across India, as shown in the Pure Storage and Zinnov report titled “Towards a Gender Equitable World”. Within the deep tech ecosystem, gender diversity stands at 23%.

Despite this positive development, it highlights the substantial ground that still needs to be covered to bridge the diversity gap in the industry. With only 6.7% of women in executive roles in GCCs and 5.1% in deep tech organisations, there is a considerable decrease in the available talent pool of women as they move up the career ladder. In GCCs, at the senior level (9-12 years of experience), the representation stands at 15.7%, the report said.

India has nearly 1,600 GCCs. In 2022-23, GCCs added 2.8 lakh employees, taking its talent base to over 1.6 million. The report stated that family and caregiving responsibilities, limited access to career advancement and leadership opportunities, and poor work-life balance are some of the key factors influencing women’s attrition.

“While India proudly leads in the number of women STEM graduates globally, their under-representation in the deep tech workforce stems from systemic barriers hindering their education and career advancement. To unlock the full potential of our talent pool, we need to take a comprehensive approach, including strategic actions to increase the enrolment of women in leading technological institutions and retaining them in the workforce,” said Ajeya Motaganahalli, VP of engineering and MD, India R&D at Pure Storage.

The median representation of women graduates from top engineering universities stands at 25% between 2020-23, which directly affects the inflow of female candidates in GCCs, especially in the deep tech sector. Despite this disparity in women’s repre- sentation, women graduates consistently outperformed in securing placements compared to the overall average in top-tier universities.

“Advancement in any industry is stagnant without equity. While deep tech has pushed the boundaries of possibility, the sobering truth is that the sector has only 5.1% women at the executive level. Interventions to solve the talent pipeline issue and create work environments enabling women to thrive have become an urgent necessity. Initiatives like leadership development programmes, returnship opportunities, and flexible work arrangements introduced by GCCs are a positive start, but true progress demands unwavering commitment and consistency from the entire ecosystem,” said Karthik Padmanabhan, managing partner at tech advisory firm Zinnov.

See also

Global capability centres: India