Hyderabad State, 1908

This article has been extracted from THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908. OXFORD, AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. |

Note: National, provincial and district boundaries have changed considerably since 1908. Typically, old states, ‘divisions’ and districts have been broken into smaller units, and many tahsils upgraded to districts. Some units have since been renamed. Therefore, this article is being posted mainly for its historical value.

Contents |

Hyderabad State

Physical aspects

A Native State better known as the Domi- nions of His Highness the Nizam, lying between 15° 10' and 20° 40' N. and 74° 40' and 81° 35' F.., with an area of 82,698 square miles. It forms a polygonal Physical tract occupying almost the centre of the Deccan plateau. Berar and the Central Provinces touch it on the north, and the Khandesh District of the Bombay Presidency on the north-west; on the south it is bounded by the Kistna and Tungabhadra rivers, which separate it from the (luntur, Kurnool, and Bellary Districts of Madras ; on the west it is bounded by the Ahmadnagar, Sholapur, Bijapur, and Dharwar Districts of Bombay ; and on the east by the Wardha and Godavari rivers, and the Kistna District of Madras. The State is equal in area to the Madras Presidency, minus the Coromandel Coast and Coimbatore, or a little more than two and a half times the area of Ireland, or one and two-fifths of the combined areas of England and Wales.

The country is an extensive plateau, with an average elevation of about 1,250 feet above the level of the sea, but with summits here and there rising to 2,500 and even to 3,500 feet. It is divided into two large and nearly equal divisions, geologically and ethnologically distinct, separated from each other by the rivers Manjra and Godavari. The portion to the north and west belongs to the trappean region, that to the south and east being granitic and calcareous. There is a corresponding agreement between the two ethnological elements. The trappean region is inhabited by Marathas and Kanarese speakers, and the granitic country by Telugu speakers. The trappean or black cotton soil country is a land of wheat and cotton ; while Telingana, or the granitic region, is a land of rice and tanks. The difference between these two tracts is very marked. The trap or black cotton soil region is covered with luxuriant vegetation, with cliffs, crags, and undulating hills. The soil resulting from the decomposition of trap is of a dark colour, and very fertile ; and, being argillaceous, it retains moisture for a considerable time. In the granitic and calcareous region, on the other hand, the hills are bare of vegetation, but the plains are covered with scattered brushwood of every description ; dome-shaped hills and wild fantastic boulders and tors abound in many parts, giving the region a gloomy aspect. The soil derived from the decomposition of the granite is sandy, and does not retain moisture. Consequently the rivers in this region run dry during the hot season,

In 1905 the administralive units of the State, from Divisions to taluks, were com- pletely reconstituted. The text generally refers lo their constitution before the rearrangement, but the main changes are explained in the paragrapli on Adminis- tration and in the individual articles. and this gives rise to the necessity of storing water in artificial reservoirs, known as tanks, with whicli the whole of the Telingana tract is studded. The surface of the country has a general slope from north-west to south-east, the main drainage being in this direction ; the country to the extreme north-west corner near Aurangabad has an average altitude of about 2,000 feet above sea-level, falling imper- ceptibly to near 1,200 feet at Raichur and to between 800 and 900 feet near Kurnool.

The following arc the chief hill and mountain ranges in the State. The Balaghat (/^^/a = ' upper,' ,^//J/ = a 'mountain pass') is a range of hills which extends almost east and v.-est from the Biloli tdhik in the east of Nilnder District, through Parbhani, till it reaches Ashti, in Bhir District, with a length in Hyderabad of 200 miles and an average width of about 4-| miles. A spur of this range branches off through tracts lying between the rivers Sina, Manjra, and Kagna, extending from Ashti in Bhir District through Osmanabad, and terminating in Gulbarga District. A spur of the Balaghat runs between the rivers Godavari and Manjra, and passing southwards from the west of Biloli in Nander District reaches Kaulas in Indur District.

The Sahyadriparvat runs along the north, from Nirmal in Indur District in the east, and passing through the District of Parbhani and the province of Berar reaches Ajanta, and proceeding farther in a westerly direction enters the Bombay District of Khandesh. Its total length within the State is about 250 miles, for about 100 miles of which it is styled the Aj|anta Hills.

Another range, known as the Jalna Hills, starts from the Daulatabad fort in Aurangabad District, and proceeds eastward as far as Jalna in the same District, and thence passes into Berar, having a length of 120 miles.

The Kandikal Gutta, 50 miles in length, extends from Warangal District in a north-westerly direction through the Chinnur taluk of Adilabad District. It is also called the Sirnapalli range.

The principal rivers are the Godavari and the Kistna, with their tributaries the Tungabhadra, the Purna, the Penganga, the M.^njra, the Bhima, and the Maner. There are, besides these, many other smaller streams, such as the Musi, the Windi, the Munair, and others.

The Godavari enters the State at Phultamba in Aurangabad District, flows through it and the Districts of Parbhani, Nander, Indur, and Adilabad for a distance of 500 miles, and changing its course at the north-east corner of Elgandal District, continues in a south-easterly direction for about 170 miles, forming the eastern boundary of El- gandal and Warangal Districts, until at Paranthpalli, in the latter Dis- trict, it enters the Godavari District of Madras. It is joined by the Manjra, which rises in the Patoda taluk of Bhir District, after a course of 387 miles through Ehir, Osmanabad, Bidar, Medak, Nander, and Indur Districts.

The Kistna crosses the border of the Bijapur District of Bombay at Echampet in Lingsugur District, and taking a south-easterly course traverses the Districts of I^ingsugur, Raichur, Mahbubnagar, Nalgonda, and warangal, forming the southern boundary of the last three Dis- tricts and consequently of the State. Its tributary, the Bhima, enters Hyderabad at Urchand in Gulbarga District from the Sholapur District of the Bombay Presidency, flows through Gulbarga and RaichCir, and falls into the Kistna in the latter District. The Tunga- bhadra, another tributary of the Kistna, touches Lingsugur District at Madlapur, and flows in a north-easterly direction until it reaches Raichur District, whence it flows due east until its confluence with the Kistna near Alampur in the same District. The Tungabhadra separates Lingsugur and Raichur from the Bellary and Kurnool Districts of Madras.

The Penganga rises in the Sahyadriparvat and runs east along the north of Hyderabad, separating Parbhani, Nander, and Sirpur Tandiir (now Adilabad) L)istricts from the southern parts of Berar. In Sirpur Tandur it flows along the western and northern borders until it falls into the Wardha river, north of the Rajura taluk.

This wide expanse of country presents much variety of surface and feature. In some parts it is mountainous, wooded, and picturesque ; in others flat or undulating. The champaign lands are of all descrip- tions, including many rich and fertile plains, much good land not yet brought under cultivation, and numerous tracts too sterile ever to be cultivated at all. Aurangabad District, besides its caves at Ajanta and Ellora, presents a variety of scenic aspect not met with elsewhere. The country is undulating in parts, with steppe-like ascents in some places and abrupt crags and cliffs in others.

Properly speaking there are no natural lakes in the State, but some of the artificial sheets of water are large enough to deserve the name. These are reservoirs formed by throwing dams across the valleys ot small rivulets and streams, to intercept water during the rains for irriga- tion purposes, and they number thousands in the Telingana tract. The largest and most important is the Pakhal Lakk in the Narsampet tCiluk of Warangal District, the dam of which is 2,000 yards long, and holds up the water of the river Pakhal. Its area is nearly 13 square miles, and its lenglli and braultli are respectively 8,000 and 6,000 yards.

The geological formations of the Hyderalxid State are the recent and ancient alluvia, lateritc, Deccan tra[), Gcmdwana, Kurnool, and Cudda- pah, and Archaean, 'i'hose nujst largely develoi^ed are the Deccan trap and the Archaean, covering immense areas in the north-western and soulh-easlcrn portions of the territory respectively. The Gond- wana rocks extend for a distance of 200 miles along those portions of the valleys of the Godavari and Pranhita which form the north-east- ern frontier of the State. Though the main area of the Cuddapah and Kurnool formations lies in the Madras Presidency, south of the Kistna, they are found in the valley of that river along the south- eastern frontier for 150 miles, and again in the valleys of the Kistna, the Ehima, and their tributaries in the south-west.

The oldest formation, the Archaean, consists largely of massive granitoid rocks, particularly well developed round Hyderabad, which extend eastwards past Khammamett as far as the eastern corner of the State, where the rocks become more varied and schistose, con- taining mica and hornblendic schists, beds of magnetite, metamorphic limestones, and other rocks. Again, a great series of schistose rocks occurs between the Kistna and Tungabhadra in the south-western Dis- tricts, which has been mapped and named as the Dharwar system. This consists of hornblendic, chloritic, and argillaceous schists, epidio- rites, and beds of quartz, associated with varying amounts of hematite and magnetite, representing a highly metamorphosed sedimentary and volcanic series. Except the groups mentioned above, the Archaean formation has not been studied in sufficient detail to define the character and boundaries of its component petrological types. The long narrow bands forming the Dharwar schist outcrops in the last-mentioned region constitute deeply folded and faulted synclines, embedded within older crystalline schists and gneiss, and injected by later granitoid intrusions. They are intersected by auriferous veins, of great economic importance, leading in the past to considerable mining activity which is now being resumed. Innumerable basic volcanic dikes occur throughout the Archaean area, some of which are epidiorites, probably of the Dharw'ar period, while others, consisting of augite-dolerite or diabase, with micro- pegmatitic quartz of a later period of volcanic activity, are connected with the lavas of the Cuddapah group.

The outcrop of the Cuddapah series north of the Kistna river, con- sisting of quartzites, slates or shales, and limestones, has been divided into several unconformable groups, upper groups of which principally occur in this State. The Kurnool series, which is unconformable to the Cuddapah, consists of quartzites, limestones, and shales, which are not so altered and indurated as those of the Cuddapah. Both these have long been known as the diamondiferous sandstones of Southern India. The gems occur principally towards the base of the Kurnools. A portion of the Cuddapahs corresponds with the Bijawars of Central India, while the Kurnools are closely related to the Vindhyas. The main area of the Cuddapahs and Kurnools terminates near Jaggayya- pet, north of the Kistna. A considerable outcrop of the Cuddapahs follows the south-western border of the Godavari, its fcnmer connexion with the main area being indicated by a series of elongated ouThers, the ■largest of which lies east of Khammamett. The largest continuous spread commences north-east of Khammamett, forms the Pakhal hills, and extends to within a short distance of the Godavari and Maner con- fluence. The beds reappear north of the Godavari, and continue north- west up to the frontier of Hyderabad, where they disappear beneath the basaltic lavas of the Deccan trap. The Cuddapahs of this area are unconformably overlaid by a vast series of quartzites and conglomerates with a few slaty beds, known as the Sullavai series, which possibly represent the Kurnools. Another outcrop of the Cuddapahs, locally known as the Kaladgi series, occupies a large area in the Bombay Districts of Belgaum and ] )harwar, the eastern extremity of which lies within the Dominions. Farther to the north-east is another belt of the Kurnool strata, intercalated between the Archaean gneiss and the Deccan trap, and locally named after the Bhima river, which flows through their outcrop.

The Gondwana rocks, containing the coal-measures, and occupying an enormous area in the valleys of the Godavari and Pranhita, are divided into the Chikiala, Kota-Maleri, Kamptee, Barakar, and Tal- cher groups. The first two belong to the Upper and the rest to the Lower Gondwanas. The boundaries of this area are mostly faults, as in most of the Indian coal-fields, which accounts for their straightness and parallelism. The Talchers consist of fine buff sandstones, often of a greenish tinge, overlying greenish-grey slaty shales and sandstones, beneath which lies the well-known boulder-bed. The glacial origin of this latter formation has been thoroughly confirmed by the remarkable section in the Penganga near the village of Irai, not quite a mile above the Wardha confluence, where not only do the boulders exhibit glacial striations, but the surface of the underlying Cuddapah limestones is deeply furrowed and grooved by ice-action, as is commonly seen in glacial regions.

The Barakars are not more than 250 feet thick, but they are of great economic importance, owing to the coal-seams which they include. They consist of coal-beds, sandstones, and shales, with a few impure thin carbonaceous layers. The coal-beds are of great thickness, the Singareni thick coal averaging 56 feet.

The Kamptees rest unconformably on the Barakars and contain no coal. They consist of clays, conglomerates, and especially sandstones, many of them highly ferruginous, others calcareous, and a few manga- niferous. Their principal outcrop lies west of the Godavari, below the confluence of the Pranhita, extending almost as far as the delta.

The Lower Gondwanas are principally u|)per palaeozoic in age. The Upper Gondwanas contain mesozoic fossils. Some of the most interest- ing are those of the Kota-Maleri group, including several species of fishes and reptiles, which occur in limestone beds associated with clays. Abundant red and green clays and clayey sandstones form the most distinctive petrological feature of these beds, which rest unconformably on the Kamptees, occupying vast areas to the west of the Godavari and Pranhita. The Chikiala beds, resting on the Kota-Maleri, and consisting of highly ferruginous glassy-looking sandstones and iron bands, are unfossiliferous. Their connexion with the Gondwanas is doubtful.

The Deccan trap, consisting of bedded lava-flows of basalt and dolerite, with occasional intercalations of fresh-water deposits, known as intertrappeans, covers the western part of the State, and extends all along its northern frontier.

Ancient alluvial gravels and clays, sometimes of considerable thick- ness, occur at various parts in the valleys of the Godavari, Kistna, Tungabhadra, and some of their tributaries, indicating geographical conditions differing from the present ones. Their vast antiquity is shown by their containing the remains of extinct mammalia of pleisto- cene or upper pliocene age. The surface of the rocks is often concealed by laterite, which is a peculiar form of rock-weathering special to tropical regions. Rocks rich in iron, like the Deccan trap, are particularly liable to this form of decomposition. In the absence of laterite, the weathering of the Deccan trap produces the well-known fertile black soil, which may be in parts contemporaneous with the trap, while in the large river valleys it must have been formed or reconsolidated within a (geologically speaking) recent period, judging from the palaeolithic or even neolithic stone implements found in it. Recent alluvial flats cover considerable areas of the large river valleys, espe- cially along the Godavari below the Pranhita confluence down to the delta.

The principal mineral products of the Dominions are diamonds, gold, and coal. The first occur in the Kurnool series ; the gold in the Dharwar system in Lingsugur ; and. the coal in the Barakar, in the Godavari-Pranhita-Gondwana system, which is worked at Singareni. Rich iron ores occur in the Chikiala sandstones, and in the Dharwar schists. These products will be more fully described in dealing with Minerals.

Much of the land in the Hyderabad State is level, and a large portion of it is under cultivation, though there are tracts where arable soil has never been broken or cultivated, or where cultivation has lapsed. But wherever the ground is left uncultivated for a year or two, it becomes covered with a low jungle, consisting chiefly of Cassia auriculata and Zizyphus microphylla. Other level tracts also exist where the ground is quite unfit for cultivation. The forests contain, among the larger species, Teclona gra/idis, Diospyros iofitciUosa, Bos- ive/lia serrata, Anogeissus latifo/ia, Termmalia iomc/itosa, Dalheri:;ia laiifolia, Ougeinia daldergioides, Schreibera stvietenioides, Pterocarpus Marsupiiim, and Adina cordifolia, with smaller species like Briedelia retusa, Lagerstroemia parvifiot'a, Woodfordia floribiinda, Zizyphtts, Mori?ida, Gardenia, Bi/iea, Acacia, Baiihinia, Cochlospej-mum, Grc7via, and Phyllanthus. When ground once occupied is allowed to go out of cultivation for a short time, a similar forest speedily asserts itself, containing, besides the trees already mentioned, a considerable number of the semi-spontaneous shrubs and trees that are frequently found in the neighbourhood of Indian dwellings, such as Bombax, Erythrina, Moringa, Cassia Fistula, Anona reticulata, Melia Azadirachta, Crataeva Roxburghii, Feronia Elephantum, Aegle Marmelos, and various species of Acacia and Ficus.

In the hilly tracts the hills are often covered with forests, not as a rule containing much large timber, the leading constituent species being the same as those that grow in the level tracts and arable lands, but these are stunted and deformed. Throughout the whole State scattered trees of Acacia arabica and Acacia Catechu and toddy-palms {Borassus flabellifer and Phoenix sylvestris) are common ; the latter two are extensively cultivated on account of their sap and juice, which, when drawn and allowed to ferment, produces an intoxicating beverage largely consumed in the Telingana tract. The soils of this area are also favourable to the growth of the coco-nut, which cannot be grown even with the greatest care in the Maratha region. Around villages, groves of mango {Alangifej-a), tamarind, Bombax, Ficus bengalensis, F. religiosa, and F. infectoria, and similar species exist. The tamarind does not flourish in the Maratha Districts to the same extent as in Telingana.

A greater variety of wild animals and feathered game is not met with in any other part of India, excepting perhaps the Mysore State. Tigers and leopards are found everywhere, while bison and occasionally elephants are met with in the immense jungle about the Pakhal Lake. The high lands are resorted to by spotted deer {Cervus axis), nilgai [Boselaphus tragocamelus), sdmbar {Cervus unicolo?-), four-horned antelope, hog deer, and ' ravine deer ' or gazelle. \\'ild hog arc found in the jungles, and innumerable herds of antelope in the plains. Hyenas, wolves, tiger-cats, bears, porcupine, hare, jackals, c\;c., are in great abundance. Of the varied species of the feathered tribe in Hyderabad, may be mentioned the grey and painted partridge, blue rock and green pigeon, sand-grouse, quail, snipe, bustard, peafowl, jungle- fowl, wild duck, wild geese, and teal of various descriptions. The florican and flamingo are occasionally seen on the banks of the Godavari and Kistna.

The climate is not altogether salubrious, but may be considered as in general good, for it is pleasant and agreeable during the greater part of the year. The country being partially hilly, and free from the arid bare deserts of Rajputana and other parts of India, the hot winds are not so keenly felt. There are three marked seasons : the rainy season from the beginning of June to the end of September, the cold season from the beginning of October to the end of January, and the hot season from early in February to the end of May.

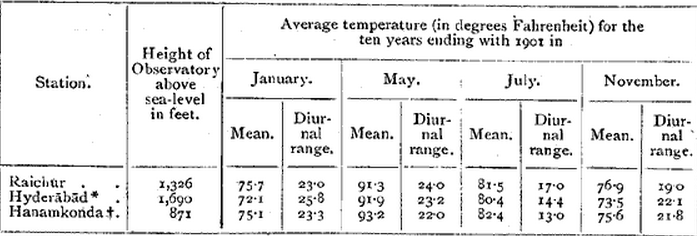

The mean temperature of the State is about 8i°. The following table gives the temperature for the three stations where observations have been taken regularly : —

The figures for January, May, and July are for ten years, and for November for eleven, t The figures for January are for three years and the rest for four.

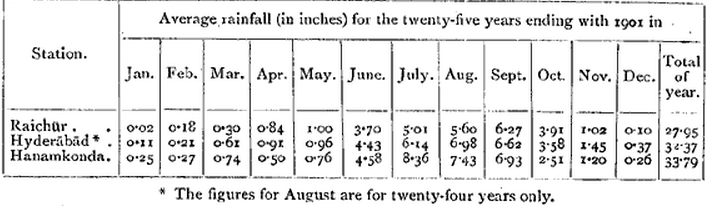

The annual rainfall is estimated at from 30 to 32 inches, principally received during the south-west monsoon between June and October. The north-east monsoon brings between 4 and 7 inches of rain. The rainfall in 1901 was 32 inches, but in 1900 the total fall amounted to only 15 inches or less than half the normal. Westerly winds blow generally from the beginning of June to the end of September ; during the ne.\t five months, from October to February, the wind blows from the east ; and in March, April, and May north-easterly winds are frequent. The following table gives the rainfall at three stations : —

History

In prehistoric times the great Dravidian race occupied the southern and eastern portions of the State together with the rest of Southern India. The Telugu-speaking division of this race constitutes the most numerous section even to the present day. The Ramayana and the Mahabharata contain traditions of Dakhshinapatha (Deccan), which forms the central portion of the State. The visit of Rama to Kishkindha, identified with the modern Vijayanagar and Anegundi, is familiar to all students of ancient literature.

It is uncertain when the invasion of the Deccan by the Aryans occurred, but the dominions of the Buddhist king Asoka (272-231 B.C.) covered the whole of Berar and a considerable portion of the north- western and eastern tracts of the vState. Among the list of conquered nations in Asoka's inscriptions occurs the name of the Pitenikas, who inhabited the city and country of Paithan, on the upper Godavari in Aurangabad District.

The Andhras were the next kings who ruled the Deccan. They are mentioned in Asoka's inscriptions, but their rise to power dates from about 220 B. c. Gradually extending their sway from the Kistna delta, they soon possessed an empire reaching to Nasik ; and towards the close of the first century of the Christian era were contending with the Sakas, Pallavas, and Yavanas of Mahva, Gujarat, and Kathiawar. Pulumayi II, who succeeded about a.d. 138, and married a daughter of Rudradaman the Western Satrap, is mentioned by Ptolemy. He was defeated by his father-in-law and thus lost the outlying portion of his dominions. About a hundred years later the dynasty came to an end, but little is known of the reasons for its collapse. It is possible that the Pallavas who ruled south of the Kistna then extended their power into Hyderabad.

The next dynasty of importance is that of the Chalukyas, who rose to power in Bijapur District about 550, and founded a kingdom spreading east and west across the Peninsula with their capital at Kalyani. Pulikesin II (608-42) ruled practically the whole of India south of the Narbada, and even came into contact with Harsha- vardhana of Kanauj. Throughout their period of supremacy, however, the Chalukyas were at war with the I'allavas, and their fortunes and dominions varied, though they continued to rule a large portion of Southern India to the middle of the eighth century, when they were displaced by the Rashtrakutas of Malkhcd in Gulbarga District. About 973, the Chalukyan dynasty was restored, and for nearly 200 years maintained its i)osition, in spite of fierce struggles with the ('holas and Hoysalas of Dorasamudra. The Chalukya power fell about iiSy to the Hoysalas and ^^^,davas, the latter of whom established themselves at Deogiri (Daulalabad). The Yadavas were the last great Hindu rulers of the Deccan, for the Vijayanagar kingdom, which was founded half a century after the advent of the Muhanmiadans, never acquired much sway in the Deccan proper.

Ala-ud-din Khilji led the first Muhammadan expedition into the Deccan, in 1294, against the Yadava ruler of Deogiri and coerced him into submission. In 1296 he assassinated his own uncle and seized the throne, and sent an expedition to Daulatabad. His first expedition was dispatched in 1303 against the Kakatlyas of Warangal, who had been estabHshed there since the middle of the twelfth century. This having failed, he sent a second under MaHk Kafur in 1309, which resulted in the submission of the Raja, and a promise to pay tribute. Ulugh Khan, who afterwards ruled at Delhi as Muhammad bin Tughlak, conducted a later campaign against Warangal, and finally broke the Kakatiya power in 1321, though not without a prolonged struggle. In 13 10 Malik Kafur was sent against the Ballala Raja of Dorasamudra (Halebid in Mysore), who was made a prisoner and lost his capital, the spoils consisting of 600 elephants, 96,000 maunds of gold, quantities of jewels and pearls, and 20,000 horses. In 13 18 Harpal, the Deogiri ruler, rebelled, but was taken prisoner and executed, and with his death ended the Yadava dynasty, after a rule of about 130 years. When Muhammad bin Tughlak ascended the throne of Delhi in 1325, the Muhammadans were masters of the Deccan from north to south, the chief Rajas of Telingana acknow- ledging their sway and paying tribute. He changed the name of Deogiri to Daulatabad and made it his capital. A few years later the imperial governors of the Deccan revolted. Their rebellion resulted in the alienation of the Deccan provinces and the establish- ment of the Bahmani dynasty.

Zafar Khan, who styled himself, according to some historians, Ala-ud-dln Hasan Shah Gangu Bahmani, or, according to a contem- porary inscription, Ala-ud-dln Bahman Shah, founded this line ; and having taken possession of the Deccan provinces, including Bidar and Gulbarga, he made the latter place his capital and commenced to reign in 1347. The Bahmani kingdom extended from Berar in the north to the left bank of the Tungabhadra in the south, and from Dabal on the west coast to the Telingana Districts in the east. Muhammad Shah, who succeeded his father Ala-ud-din in 1358, waged wars with Vijayanagar (1366) and Warangal (137 1)> ^'^^ acquired great booty from both. It is said that 500,000 Hindus were slain during his reign. He died in 1375 and was followed by his son, Mujahid Shah, whose uncle, Daud Khan, three years later, murdered and succeeded him, but was assassinated in the same year (1378). Muhammad \ the grandson of Hasan Gangu, was proclaimed king and ruled peacefully to the time of his death in 1397. His son, Ghiyas-ud- dln, only reigned two months when he was blinded and deposed by Lalchin, a discontented slave, who proclaimed the king's brother, Shams-ud-din. Firoz Khan and Ahmad Khan, the grandsons of

' Wrongly styled Mahmud by I'irishta, whose error has been unfortunately followed by many modern historians.

Bahnian Shah, who had been married to Ghiyas-ud-dln's two sisters, rose against Shams-ud-dln, and forcing their way into the darbdr, made the king and Lalchin prisoners. Firoz was proclaimed king in 1397 ; Shams-ud-din was bUnded after a reign of five months and Lalchin was put to death. Firoz marched against the Vijayanagar Raja, who had invaded the Raichur Doab in 1398, and defeated him, bringing back much plunder. In 1404 the ruler of Vijayanagar advanced to Mudgal and war broke out between the two kingdoms ; the Raja was defeated and sued for peace, which was granted on the condition that he gave his daughter in marriage to the king, besides presenting a large sum of money, and pearls and elephants, and ceding the fort of Bankapur as the marriage portion of the princess. In 141 7 the king invested the fortress of Pangal, and the Rajas of Vijayanagar and ^^^arangal and other chiefs advanced to its relief at the head of a large force.

Although Flroz's army had been decimated by a pestilence which broke out among his troops, the king gave battle, but suffered a severe defeat. The Musalmans were massacred, and Firoz was pursued into his own country, which was laid waste with fire and sword. These misfortunes preyed on his mind and he fell into a lingering disorder, which affected both his spirits and intellect, so that he finally abdicated in 1422 in favour of his brother, Ahmad Shah. Ahmad Shah marched to the banks of the Tungabhadra and defeated the Raja of Vijaya- nagar ; peace was, however, concluded on the latter agreeing to pay arrears of tribute. In 1422 Ahmad Shah sacked Warangal and obtained much plunder. He founded the city of Bidar in 1430, and died there in 1435. ^^ ^443 there was again war between the Vijayanagar Raja and the Bahmani king Ala-ud-din II, in which the latter was defeated. Ala-ud-din was succeeded in 1458 by his son Humayun, 'the cruel.' Soon after his accession, he marched to Nalgonda to quell a rebellion which had broken out in his Telingana provinces. Hearing of an insurrection at Bidar, he left his minister to carry on the campaign and returned to Bidar, and after putting to death thousands of innocent persons of both sexes his cruelties ended only with his own death after a reign of three and a half years. He was succeeded by his eldest son, Nizam Shah, who died two years afterwards (1-463), when his younger brother, Muhammad Shah III, was crowned. The reign of this prince is notorious for the execution of the great minister, Mahmild Gavan. The king died in 1482, and was succeeded by his son, Mahmud Shah, who gave himself up to pleasure and dissipation ; and the governors of provinces, seeing this state of affairs, acted independently, so that only Telingana and adjacent Districts of Bidar remained in the king's possession.

Kasim Barld now became minister, and induced the king to make war against Vusuf Adil Khan, who had taken liijapur and declared his independence. The l?ahmani forces were defeated and the king returned to Bldar. In 1504 Kasim Barld died, and his son, Amir Barid, becoming minister had the king completely in his power. About this time (15 10) Yusuf Adil Khan died, and Amir Barid attempted to reduce Bijapur. After a reign of constant vicissitude and trouble, Mahmud Shah died in 15 18. Though he was succeeded by his son, Ahmad Shah, Amir liarid remained all-powerful. Ahmad Shah died after a reign of two years, and his son, Ala-ud-din, was assassinated by Amir Barid. Two other kings, Wali-ullah Shah and KalTm-ullah Shah, sucx-ceded one another in the course of five years, the latter dying in exile at Ahmadnagar in 1527; and with him ended the great Bah- mani dynasty, which had reigned first at Gulbarga and then at Bldar for more than 180 years.

Amir Barid assumed sole charge of the affairs of the kingdom ; and after many vicissitudes and constant wars with the rulers of Bijapur and Berar, he died at Daulatalxid (1538), and was succeeded by his son, All Barid, who was the first to assume the title of Shah. In 1565 he, with the other Deccan kings, marched against the Vijayanagar Raja, and the memorable battle of Talikota was fought, which sealed the fate of the kingdom of Vijayanagar. All Barid died in 1582, and was succeeded by three other kings, the last of whom, All Barid II, was expelled by a distant relation. Amir, who continued to rule for some time after 1609, but it is not known exactly when and how his reign ended.

Kutb-ul-mulk, Sultan Kuli, a Turk of noble family, who was governor of the Golconda province under the Bahmanis, took advantage of the distracted state of the kingdom under Mahmud Shah and declared his independence, establishing the Kutb Shahi dynasty, which reigned here from 15 12 to 1687. Sultan Kuli waged wars with the Vijayanagar and Kammamett Rajas, and extended his kingdom in the north to the banks of the Godavari. He defeated the Bijapur forces near Koil- konda, and later on took Medak, Kaulas, and other forts from the Barid Shahi king of Bldar. He was assassinated in 1543 at the age of ninety, while kneeling in prayer in the chief mosque at Golconda, at the instigation of his son Jamshed Kuli, after ruling for sixteen years as viceroy and thirty-one as king. He was succeeded by Jamshed Kuli (1543), Subhan Kuli (1550), and Ibrahim Kuli (1550). The last of these allied himself with the Ahmadnagar king against the ruler of Bijapur, who had sought the alliance of Vijayanagar. In 1564 he proposed the alliance against the Vijayanagar kingdom, which led to the battle of Talikota. He died in 1581, and was succeeded by his son Muhammad Kuli. In 1603 Shah Abbas, the king of Persia, sent an ambassador to Hyderabad with valuable presents. Muhammad Kuli was succeeded in 1612 by his nephew and son-in-law Muhammad II, who died in 1626, and was followed by his son Abdullah.

When the Mughals invaded the Dcccan, the local rulers formed an alliance against them ; but after defeating the invaders, they fell out among themselves, thus enabling the imperial troops gradually to subdue the country. Shah Jahan, after rebelling against his father, fled from Burhanpur and was welcomed at Golconda by Abdullah Kutb Shah. In 1635 Shah Jahan, who had then become emperor, sent a farmdti to Golconda which was well received ; the kJiiitba was read in the name of the emperor in the chief mosque, and coins were also struck in his name. Mir Jumla, the king's minister, appealed to Aurangzeb for help against his master in 1655, and this afforded a pretext for Aurangzel) to invade the territory. Hyderabad was plundered, and Abdullah sued for peace and paid arrears of tribute. He died in 1674, and was succeeded by his nephew Abul Hasan, also called Tana Shah. After the fall of Bijapur in 1686, Aurangzeb turned his attention to Golconda, which was taken in the following year. Tana Shah was made prisoner and sent to Bidar, and thence to Daulatabad, where he died in 1704, and with him ended the line of the Kutb Shahi kings.

The house of the present Nizams was founded by Asaf Jah, a dis- tinguished general of Aurangzeb, of Turkoman descent. After long service under the Delhi emperor, distinguished alike in war and political sagacity, he was appointed Subahdar or viceroy of the Deccan in 1713 with the title of Nizam-ul-mulk, which has since become the hereditary title of the family. The Mughal empire at this i)eriod was on the verge of decline, owing to internal dissension and attacks from without. Amid the general confusion, Asaf Jah had little difficulty in asserting his independence against the degene- rate and weak occupants of the throne of Delhi, but he had to repel the inroads of the Marathfis who were harassing the west of his newly acquired territory. His independence was the cause of much jealousy at Delhi, and the court party secretly instructed Mubariz Khan, the governor of Khandesh, to oppose him by force of arms. A battle was fought at Shakarkhelda (Fathkhelda) in the Buldana District of Berar in 1724, when Mubariz Khan was totally defeated and lost his life. This battle established tlic independence of Asaf Jah, who annexed Berar, and fixed his residence at Hyderabad. At the time of his death in 1748 he was fairly established as independent sovereign of a kingdom co-extensive with the present State, including the province of ]3erar.

After his death, Nasir Jang, his second son, and Muzaffiir Jang, his grandson by one of his daughters, strove for the succession. vXt this time the English and the French were contending for supremacy in the East, and each of the claimants secured the support of one of these powers ; Nasir Jang's cause was espoused by the English, while Mu- zaffar Jang was supported by the French. The latter, however, fell a prisoner to his uncle, but, on the assassination of Nasir Jang, Muzaffar Jang was proclaimed the sovereign. Dupleix, the French governor, became the controller of the Nizam's authority. Muzaffar Jang was killed by some Pathan chiefs, and the French then selected Salabat Jang, a brother of Nasir Jang, as ruler. Ghazi-ud-din, the eldest son of Asaf Jah, who, it was alleged, had relinquished his claim at first, now appeared as a claimant, supported by the Marathas, but his sudden death put a stop to further struggles. The English and the French were now contesting power and influence in the Deccan ; but the victories of Clive in the Carnatic caused the latter to turn their atten- tion to their own possessions which were threatened, and to leave Salabat Jang to shift for himself. Nizam All Khan, the fourth son of Asaf Jah, at this juncture obtained the support of the English on the promise of dismissing the French from his service. Salabat Jang was dethroned in 1761, and Nizam All Khan was proclaimed ruler.

In 1766 the Northern Circars were ceded to the British, on con- dition that the Nizam was to be furnished with a subsidiary force in time of war, and should receive 6 lakhs of rupees annually when no troops were required, the Nizam on his part promising to assist the British with his troops. This was followed by the treaty of 1768, by which the East India Company and the Nawab of the Carnatic engaged to assist the Nizam with troops whenever required by him, on payment. In 1790 war broke out between Tipu Sultan and the British, and a treaty of offensive and defensive alliance was concluded between the Nizam, the Marathas, and the British. Tipu, however, concluded peace, and had to relinquish half of his dominions, which was divided among the allies. In 1798 a treaty was concluded between the Nizam and the British Government, by which a subsidiary force of 6,000 sepoys and a proportionate number of guns was assigned to the Nizam's service, who on his part agreed to pay a subsidy of 24 lakhs for the support of the force. On the fall of Seringapatam and the death of Tipu Sultan, the Nizam participated largely under the Treaty of Mysore (1799) in the division of territory, and his share was increased because of the Peshwa's withdrawal from that treaty.

In 1800 a fresh treaty was concluded between the Nizam and the British, by which the subsidiary troops were augmented by two battalions of infantry and one regiment of cavalry, for the payment of which the Nizam ceded all the territories which had accrued to him under the treaties of 1792 and 1799, known as the Ceded Districts. The Nizam on his part agreed to employ all this force (except two battalions reserved to guard his person), together with 6,000 foot and 9,000 horse of his own troops, against the enemy in time of war. About 1803 Nizam All Khan's health was in a precarious condition, and Sindhia and Holkar, disappointed by the reinstatement of Baji Rao, the last of the Peshwas, by the British, prepared to resort to arms. To meet the preparations made by the Marathas, the subsidiary force, consisting of 6,000 infantry and two regiments of cavalry, accompanied by 15,000 of the Nizam's troops, took up a position at Parenda on the western frontier of the Nizam's Dominions. General Wellesley was ordered to co-operate with this force in aid of the Peshwa, with 8,000 infantry and 1,700 cavalry. But before the arrival of the General at Poona, Holkar had left, and on his way to Malwa had plundered some of the Nizam's villages, and levied a contribution on Aurangilbad. On hearing of this. Colonel Stevenson advanced towards the Godavari with the whole force under him, and was joined by General Wellesley near Jalna. The next day (September 23) the memorable battle of Assaye was fought by General Wellesley, followed shortly afterwards by the battle of Argaon, which completely crushed the Marathas, and secured the Nizam's territories.

Nizam All Khan died in 1803, and was succeeded by his son, Sikandar Jah. In 1822 a treaty was concluded between the British and the Nizam, by which the latter was released from the obligation of paying the chauth to which the British had succeeded after the over- throw of the Peshwa in 18 18.

On the death of Sikandar Jah in 1829, his son Nasir-ud-daula suc- ceeded. In 1839 a Wahhabi conspiracy was discovered at Hyderabad, as in other parts of India. An inquiry showed that Mubariz-ud- daula and others were implicated in organizing the movement against the British Government and the Nizam. Mubariz-ud-daula was im- prisoned at Golconda, where he subsequently died. Raja Chandii Lai, who had succeeded Munir-ubmulk as minister, resigned in 1843, and Siraj-ul-mulk, the grandson of Mir Alam, succeeded him. In 1847 a serious riot took place between the Shiahs and the Sunnis, and about fifty persons lost their lives in the riot. Siraj-ul-mulk, who- had been removed in the same year, was reinstated as minister in 1851. As the pay of the Contingent troops had fallen into arrears, a fresh treaty was concluded in 1853, and Districts yielding a gross revenue of 50 lakhs a year were assigned to the British. The Districts thus ceded consisted, besides Berar, of Osmanabad (Naldrug) and the Raichiir Doab. By this treaty the British agreed to maintain an auxiliary force of 5,000 infantry, 2,000 cavalry, and four field batteries ; and it was stipulated that after paying the Contingent and certain other charges and interest on the Company's debt, the surplus was to be made over to the Nizam. The Nizilm, while retaining the full use of the sub- sidiary force and Contingent, was released from the unlimited obligation of service in time of war ; and the Contingent ceased to be part of the Nizam's army, and became an auxiliary force kei)t by The British Government for the Nizam's use. A week after the conclusion of this treaty Siraj-ul-mulk died and Nawab Salar Jang, his nephew, was appointed minister.

Nasir-ud-daula died in May, 1857, and was succeeded by his son, Afz.il-ud-daula. This was a critical period for Hyderabad, as the Mutiny which convulsed the whole of India affected this State also. It was feared that, if Hyderabad joined the revolt, the whole of Southern India as well as Bombay would rebel. But though His Highness was urged by some of his reckless advisers to raise the standard of revolt, he listened to the good counsels of his faithful minister, Salar Jang, and cast in his lot with the British with unshaken loyalty. After the storm of the Mutiny had subsided, the British Government, in recognition of the services rendered by the Nizam, modified the treaty of 1853; and by a treaty of i860 Osmanabad (Naldrug) and the Raichur Doab, yielding a revenue of 21 lakhs, were restored, and a debt of 50 lakhs was cancelled, while certain tracts on the left bank of the Godavari were ceded and the Assigned Districts of Berar, yielding a revenue of 32 lakhs, were taken in trust by the British for the purposes specified in the treaty of 1853. Presents to the value of £10,000 were bestowed upon His Highness, and his minister and other noblemen were also rewarded. Afzal-ud-daula was made a G. C.S.I, in i86r.

The present Nizam, Mir Mahbub Ali Khan Bahadur, succeeded on his father's death in 1869. Being only three years old, a regency was constituted for the administration of the country, with Sir Salar Jang I as regent and Nawab Shams-ul-Umara as co-regent, the Resident being consulted on all important matters concerning the welfare of the State. On the death of the co-regent in 1877, his half-brother Nawab Vikar- ul-Umara was appointed co-administrator; but he also died in 1881, Sir Salar Jang remaining sole administrator and regent till his death in 1883.

Not being fettered in any way, the great minister pursued his reforms with untiring effort. The four Sadr-ul-Mahams or depart- mental ministers, who had been appointed in 1868, managed the Judicial, Revenue, Police, and Miscellaneous departments under the guidance of the minister, who, besides instructing them in their work, had direct control over the Military, Afansab, Finance, Treasury, Post, Mint, Currency, and State Railway departments. Transactions with the British Government, His Highness's education, and the manage- ment of the Sarf-i-khds domains also received his personal attention. A revenue survey and settlement were taken in hand and completed in the Maratha Districts, civil and criminal courts were established, stamps were introduced, the Postal department was placed on a sound basis, and the Municipal, Public \\'orks. Education, and Medical departments received their due share of attention. Thus almost every department of the British administration was represented in the State, and worked with creditable efficiency under the guiding s{)irit of the great minister. In particular, the finances of the State, which had become greatly involved, were much improved.

In 1884 His Highness Mir Mahbub Ali Khan, having attained his majority, was installed by Lord Ripon. Sir Salar Jang II was ap- pointed minister, and was followed in 1888 by Sir Asman Jah. In 1892 a Code, known as the Kdmcncha-i-Mubdrak ('the auspicious code '), was issued for the guidance of the minister, and this was followed by the establishment of a Council composed of all the ministers of the State. In the following year Sir Vikar-ul-Umara became minister, and several changes were effected in various depart- ments of the administration. Maharaja Sir Kishen Prasad Bahadur, the Peshkar, was appointed minister in 1 901, and still holds that office.

In November, 1902, the Assigned Districts of Berar were leased in perpetuity to the British Government at an annual rental of 25 lakhs, a most important event in the history of the State.

Many objects and places of historical and archaeological interest are found scattered throughout the State. Among the most noteworthy are the caves of Ellora, Ajanta, Aurangabad, and Osmanabad (Dharaseo). Of the numerous forts may be mentioned those at GOLCONDA, GULBARGA, WaRANGAL, RaICHUR, MuDGAL, PaRENDA, and Naldrug. Besides these, Hindu temples of various descriptions are found in every part of the State^ some of them of great antiquity, such as the 'Thousand Pillars' temple at Hanamkonda, and the temples at Tuljapur and Ambajogai.

The oldest type of architecture is of a religious character, and is represented by the caves already mentioned, which belong to Buddhist, Jain, and Brahmanical styles of architecture. Numbers of other caves are found at places of less importance. The temple at Hanamkonda, the temple and its ruined courtyard in the fort of Warangal, and numerous others, are good specimens of Hindu religious architecture. Among the most remarkable specimens of Musalman architecture may be mentioned the mosque in the old fort of ( lulbarga ; the Mecca and jama Masjids, the Char Minar, the Char Kaman, the Dar-ush Shifa (hos[)ital), and the old bridge on the Musi, all in the city of Hyderabad ; the tombs of the Kutb Shahi kings near Golconda; those of the Bahmani and Barld Shahi kings near the city of Bidar, and that of Aurangzeb's wife at Aurangabad. Besides these, there are numerous other examples of both Hindu and Musalman architecture, now in ruins, such as the palaces of (lolconda, Bidar, Gulbarga, and Daulatabad.

See also

For a large number of articles about Hyderabad State, extracted from the Gazetteer of 1908 (as well as other articles on Hyderabad State) please either click the 'India' link (below, left) and go to Hyderabad State (under H) or enter ' Hyderabad State ' in the 'Search' box (top, right).

Hyderabad State, 1908