Hyderabad State, Agriculture 1908

This article has been extracted from THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908. OXFORD, AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. |

Note: National, provincial and district boundaries have changed considerably since 1908. Typically, old states, ‘divisions’ and districts have been broken into smaller units, and many tahsils upgraded to districts. Some units have since been renamed. Therefore, this article is being posted mainly for its historical value.

Contents[hide] |

Agriculture

The soils of the Hyderabad State may be divided into two main divisions. Those of all the Telingana Districts may be classed gener- ally under three kinds, black, red, and sandy; and those in the Maratha Districts may be similarly classed in three divisions, black, red, and a mixture of the two. Locally, a number of varieties are distinguished in Telingana. Thus, utcha regar is dark in colour and plastic when wetted, and consists chiefly of alluvium, with a good supply of lime and little silica. Katta regar is a stiff loam, containing less lime than utcha regar and little soluble matter. Raura is a good garden soil, containing 7 per cent. of lime in a pulverized state. Rauti zamm is also a garden soil, containing only 5 per cent, of lime. So/a zamin is greyish in colour, and resembles rauti zam'in. It is used for the ahi rice crop, and is manured by herding cattle, goats, and sheep on it. Chunaka regar is a rough aluminous soil, containing 12 per cent, of lime, and is best suited for Jowdr and pulse. Chauka regar or milwa is a mixture of red and black soils, with very little lime. Chalka or rcva zaml?i is a finely pulverized reddish soil, with sand and traces of lime, and is well suited for rainy season crops. Yerra chauka is similar in every respect to chalka zann?i, but not so finely powdered. The Marathwara soils are called ngar (black), masab (red), or mihva (mixture). The soils of the higher tracts are heavy and rich in alumina, wliile those found on the plains are light and loamy ; but neither is of very great depth. Broadly speaking, they are derived from the disintegration of basalt and amygdaloid wacke, the former giving rise to the stiff black soil, and the latter forming a friable earth. But when the black soil is mixed with the light friable earth, the result is a rich loam, which is more retentive of moisture than the others.

The climate of the Maratha Districts is generally hot and dry from March to the end of May, and temperate during the remaining months ; while that of Telingana is hot and damp from March to the end of September, and temperate for the rest of the year. More than three- fourths of the total rainfall, or about 23 inches, is generally received between June and September, the remainder falling between October and November.

Yellow jowdr, bdjra, sesamum, cotton, tuar and other pulses form the khar'if ox monsoon crops; and gram, barley, cotton, and linseed are the chief rabi or cold-season crops. The total area of Government lands cropped in 1901 was 30,240 square miles, of which 94 per cent, was devoted to ' dry crops,' and 6 per cent, was irrigated.

In the Maratha country only two crops are raised, the rabi and the khar'if; while in Telingana there are five crops, the dbi and tdbi for rice, and the khar'if, rabi, and mdghi for 'dry crops,' the last being intermediate between the khar'if and rabi.

As regards Marathwara, the extent of the khartf and rabi crops depends upon the rainfall. If the monsoon commences in June, khartf crops are largely sown at the beginning of the season ; but if the rains are late and the time for the /^//^r//" sowing has passed, then more land is reserved for the rabi. In Telingana, where there is a smaller extent of rabi lands, the khar'if sowing proceeds as late as July, closely followed by the mdghi sowing. Certain kinds of rice may be sown in the dbi so late as the beginning of August, if the rains are late ; and the tdbi or hot-season rice crop is sown ixom December up to the end of February.

The cultivator begins preparing his land for the khar'if sowings in December or January, and for the rahi during the monsoon, whenever there is a break in the rains. The re^ar is ploughed with the large plough or ficli^ar, drawn by eight bullocks, only once in seven or eight years, the bakkhar or harrow being considered sufficient in intei mediate years. The Telingana soils, being mostly sandy and finely divided, require only slight ploughing and harrowing. The land is ploughed first in one direction, and the second ploughing is done at right angles to the first. The ploughing is repeated till the soil is perfectly pulverized and clean.

The land thus prepared is then ready to receive the seed ; and after the first shower or two, on the breaking of the monsoon in June, khar'if sowings are commenced. In Telingana, after a few good showers have fallen, the land for rice cultivation is ploughed by buffaloes and left for a few days. The seed, which has been soaked beforehand and has sprouted, is now sown broadcast in the fields and ploughed in. But in fields irrigated from large tanks, the preparation of the ' wet ' lands begins even before the monsoon. For the rabi sowings, the land, which has been ploughed during tjie breaks in the rainy season, is sown in September or October, as at this time there are usually autumn showers which help the germination of the seed. For the tabi or hot-season rice crop, the land is first soaked with water from tanks and wells. The sowings proceed for two and even three months, from the beginning of December to the end of February.

The Maratha cultivator has his kharif and rabi crops weeded three or four times during the season ; the Telingana ryot, on the other hand, is generally careless, weeding both crops only once or twice. His attention is chiefly devoted to the rice crop, which pays him best, and he weeds that three or four times during the season.

YeWow Jo'U'dr, bajra, and the rainy season rice ripen about Decem- ber ; and white Jowdr, gram, wheat, barley, and the hot-season rice ripen from April to the end of May.

Cotton is extensively raised in all the black-soil Districts, as well as in Telingana, wherever there is a suitable soil for its production. The short-stapled variety is the only kind which the cultivator grows, as he finds it easiest to produce. In the Districts served by railways, cotton-ginning and pressing factories are taking the place of the old system of hand-ginning ; and within the last four years several of these factories have been opened in those Districts, the railway having made it possible for the machinery required to be conveyed to parts where it was impossible to transport it in carts. Railway extension has also given an impetus to the cultivation of cotton and superior cereals. Of the total population of the State in 1901, 5,132,902, or 46 per cent., were supported by agriculture. Of these, 58,858 were land- holders or rent receivers, 3,454,284 were rent payers, 186,671 were farm servants, and 836,972 were field labourers.

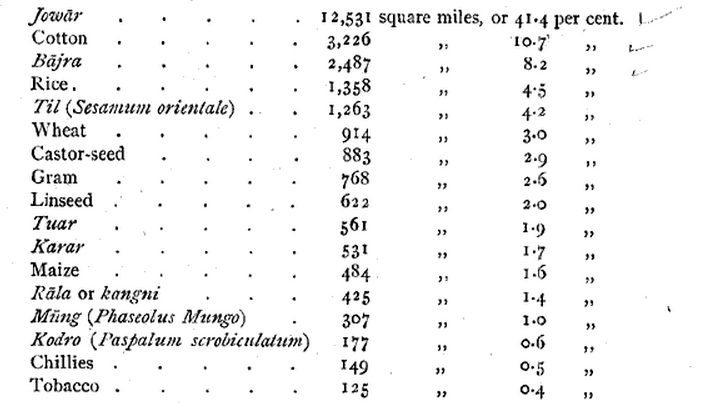

The principal crops in the Maratha country consist oi jowdr, bdjra^ wheat, cotton, linseed, and pulses ; and those in Telingana are rice, yellow jo2vdr, bdjra, castor-seed, sesame, and pulses. The staple food of the people of Marathwara consists oi jowdr, bdjra, and, to some extent, wheat ; while in Telingana, rice, joivdr, and ddjra are con- sumed. Pulses and inferior grains of many kinds are grown every- where. Oilseeds include linseed, sesame (gingelly), karar, and castor-seed, the two last being grown very largely in the Telingana Districts. Besides cotton, san-h.em\) and ambdri are the principal fibre-plants, while aloes and bhendi fibre are not unknown. Large quantities of chillies are grown everywhere, and zira (caraway) and ajivain {Ligiisticum Ajouan) are also grown in the Districts of Bidar, Atraf-i-balda, and Sirpur Tandur. In 1901 the areas occupied by the several important crops and their percentages to the total area cropped were as follows : —

The yield per acre of different cro[)s varies so much thai it is dinicult to give a fair average ; the weight of rice, for instance, ranges between 3 cwt. and 23 cwt. per acre. An attempt, however, has been made to give an average from figures obtained from the several Districts. Raw sugar, 18^ cwt. ; rice, 10^ cwt. ; Jowdr, 2^ cwt. ; wheat, 2^ cwt. ; bdjra, 2\ cwt. ; sd7vdH, 2^ cwt. ; /:///////, 2 cwt. ; castor-seed, 2 cwt. ; gram, i| cwt. ; .sesame, i^ cwt.; linseed, li cwt.; and cotton, 641 lb.

All the rice and sugar-cane fields arc manured, the latter very heavily. The manure generally used is that obtained from the village cattle, and the sweepings from the village, and from leaves and branches of trees. Jowdr and wheat in the reg^ar receive no manure. Rotation of crops in the Telingana Districts is Ajllovved in the inferior kinds of soils called chalka. When waste lands are first prepared, oil- seeds are sown for the first year ; the next year yellow jowar is grown, and in subsequent years they are put under sdivdn {Fanicuiii fruinen- taceuvi) and kodro iyPaspalum scrobiculatum). In lands of a better description, if the soil has become exhausted, jowdr is followed by cotton. \tW.Q\s joivdr, being a very exhausting crop, is never grown for two successive seasons on the same land. Where new land is of better cjuality, such as regar and mihva, and is suited for rabi crops, it is usual first to sow kiilthi {Dolichos biflorus), lakh, or castor-seed.

These are followed in the next year by kiilthi, gram, or peas. In the third year jowdr is grown, mixed with linseed or kardi gram ; after that, jowdr and kulthi are sown every alternate year. In rice lands no regular rotation is followed, but sugar-cane and betel-leaf are sometimes raised. In the Maratha Districts the rotation is as follows. When waste land is prepared for the kharif sowing, it is first put under bdjra or cotton ; and for two or three years afterwards only bdjra is raised. Then, successively, mung, iird, matt, or j'rt^z-hemp is grown ; and when the land is in a fit condition for being ploughed, a tiiar crop follows. The roots of this crop strike deep into the soil and loosen it, thereby making ploughing easy. When waste land is prepared for rabi cultiva- tion, jowdr or kardi is sown first, followed by wheat or jozvdr for the next four or five years. In ' wet ' cultivation sugar-cane is followed by rice in the next year.

Oranges are extensively grown in and around Aurangabad, Osman- abad, Parbhani, and Nirmal, but at Hyderabad and other places they are found only in private gardens. Ordinary mangoes are produced everywhere, but very superior grafted mangoes are grown in gardens around Hyderabad. During the rainy season, country vegetables are raised in all parts, but English vegetables are grown only at Hyder- abad, its suburbs, and at Secunderabad, and also at some District head-quarters. Excellent grapes were formerly grown at Daulatabad, and an attempt is being made to revive their cultivation.

The area under cultivation has considerably increased during the last twenty years. Large tracts of unoccupied cultivable land are still to be found in the Sirpur Tandur, Mahbubnagar, Warangal, Elgandal, and Indur Districts of Telingana. In the Maratha Districts the whole of the cultivable land has been taken up. The ryots have taken no interest in improving the quality of their crops by selection of seed, or by the cultivation of new varieties, or by introducing improved agricultural implements.

In the Maratha tract, a large heavy plough is used for breaking up the hard black soil, which is drawn by four or five yoke of cattle, but in Telingana a light plough is employed. Other implements arc bullock-hoes, the bakkhar (harrow), and the tippaii (seed-drills). The ordinary mot or leathern bucket is the most common water-lift, and is worked by a pair of bullocks. On the banks of rivers and streams, the ydtam or bhiidki (a lever-like contrivance) is used by one or two men.

There is no agricultural department in the State at present. The duties of a department of Land Records are performed by the Revenue department. Advances for the construction of wells are given by the State in times of scarcity and famine. The well and field are assigned as security, and the loan is repaid by instalments, interest being paid at 6 per cent, per annum. The cultivators are often largely indebted to the money-lender, and frequently become tenants of their creditors. Money is usually advanced by professional money-lenders, but wealthy agriculturists also lend money. Agricultural banks established on sound principles would probably succeed and would be beneficial to the cultivators. The ordinary rate of interest on money advanced is nominally 25 per cent, for the season. The money-lender advances a loan on the security of the future crop, and at harvest time receives 25 per cent, as interest in cash or in kind, at prices ruling at the time, so that the real interest is about 50 per cent, per annum.

With the exception of the white cattle of Eastern Telingana, the Khammamett and Devarkonda cattle, and the small bullocks of Adilabad District and the Amrabad idh/k, no special breeds of cattle are to be found in the State. The white cattle are indigenous to the country, and are a hardy stock, with black-tipped tails. The Khammamett and Devarkonda breeds are much stronger than the white cattle, and resemble the Mysore breed. The Sirpur Tandur and Amrabad bullocks are of small size, but are fast trotters. The waste lands and forests of the Telingana Districts are the pasture- grounds where they breed. Horses adapted for military and general purposes were formerly reared in large numbers, but the importation of Arabs and Australian horses has diminished the demand. The Government maintains a few Arab sires in some of the Maratha and Telingana Districts, and it is believed that the result has been satis- fectory. The Deccan ponies are still noted for their surefootedness, hardiness, and powers of endurance. The other animals, such as buffaloes, goats, and shee}), are all of the ordinary type. The Marath- wara buffaloes are very superior milch cattle, and fetch double or treble the price of the ordinary buffaloes of Telingana. Sheep and goats of the ordinary kind are bred everywhere. In most of the Maratha districts, goats of the Gujarat breed are reared, which gene- rally yield a good su[)ply of milk. The [)rice of cattle varies from Rs. 40 to Rs. 150 or even Rs. 200 per pair ; that of ponies from Rs. 15 to Rs. 150 each. Milch buffaloes in Telingana are worth from Rs. 30 to Rs. 45, hut \\\ the Mariltha Districts they fetch from Rs. 50 to Rs. 150. Slieep and goats are sold at from Rs. 2 to Rs. 3-8 per head, and milch goats at from Rs. 7 to Rs. 20 or Rs. 25.

The last famine caused great mortality among cattle in the famine- stricken districts. Grazing lands have been set apart, but in dry seasons the grass in them is very poor. Kadbi, or jowdr stalks, form the chief fodder supply, of which more than sufficient is raised in good years, and large quantities are stacked to meet requirements in times of scarcity.

Until recently (1897), a great horse fair was held annually at Malegaon, in Bidar District, at which a large number of horses and cattle were sold ; but for several years past the fair has not taken place owing to the prevalence of plague. At Hyderabad there is an extensive horse mart. In every District weekly or monthly horse and cattle fairs are held.

The Maratha country being composed of black soil, there is not so much necessity for irrigation as in Telingana ; the black soil has the power to retain moisture, which is further supplemented during the cold season by a copious deposit of dew, which supplies the crops with moisture sufficient for their growth and maturity. Where rice, sugar-cane, and garden produce are raised, the chief sources of supply are wells. The Telingana soils being sandy, it becomes of paramount importance to store water ; and for this purpose advantage has been taken of the undulating character of the ground. Dams have been thrown across the valleys of streams and gorges between hills, and rain- water which falls over a large catchment basin is thus collected, and made available for purposes of irrigation by means of sluices.

Besides the tanks and kuntas or ponds, irrigation is carried on by means of wells generally, and by means of canals and anicuts in certain districts. For rice, sugar-cane, and turmeric the land is constantly watered as long as the crops are standing, while bdghat, or garden lands, require only occasional irrigation. Wheat and barley are usually sown near wells and are watered from them once a week. Across the Tungabhadra, in Lingsugur District, a series of anicuts have been constructed to hold up the water, which is directed into side channels and is used for supplying tanks and lands along the banks of the river. There are several anicuts in a length of 30 miles on the Tungabhadra, the ! principal one being at Kuragal, which extends completely across the river. All of these anicuts were built many years ago, and no statistics are obtainable regarding their cost. A new project is now under construction for taking water from the Manjra river in Medak District for irrigation purposes and the supply of tanks.

The water from Government tanks is utilized for irrigating the ' wet ' lands, which pay a water tax. There are altogether 370 large tanks and 11,015 kiDiias or ponds, besides 1,347 channels, in the State. The large tanks are maintained by the Public Works department, while the smaller ones, as well as kiintas, are in charge of Revenue ofticers ; but since the introduction of the dastband system, zaminddrs and local officials and others have taken up some of the breached tanks, receiving a certain percentage for their maintenance after reconstruction. These, however, are mostly tanks of no very large size.

Most of the tanks — such as the Husain Sagar, the Ibrahimpatan, the Mir Alam, the Afzal Sagar, the Jalpalli, and many other large tanks, as well as irrigation channels — were constructed by the former rulers or ministers of the State. The mincer tanks are the work of zamttiddrs. No complete record is available as to the actual capital outlay, but those constructed in recent years will be described in dealing with Public Works.

The land served by wells is irrigated by the old primitive method of lifting the water by means of large buckets drawn by bullocks. The total number of wells in the State is 123,175. Where any supply channels from a river or a perennial stream are constructed to carry water to tanks, the ryots sometimes bail out water on either side of the channel by means of hand-buckets called bhurki or guda, and so get a constant flow. Masonry wells cost between Rs. 400 and Rs. 600, and those lined with stone without any mortar between Rs. 200 and Rs. 300 ; such wells have two bullock runs and two buckets, and are capable of irrigating 4 to 5 acres of rice or sugar-cane, and 10 acres of garden land.

Rent,Wages,and Prices

As ryotwdri is the prevailing revenue system throughout Hyder- abad, the sum paid by the cultivator represents the land revenue, which will be dealt with later. In the case of deserted villages, which have been leased by the ^^^ pdces^^' State, the holder is free to charge his tenants what rent he pleases, provided the rates do not exceed those previously l)aid to the State. The pattaddrs or ryots, who hold directly from the State, sometimes sublet the whole or a part of their lands or take partners called shikmlddrs. The latter cultivate land in part- nership with the pattaddrs, and divide the produce and expenses in jjroportion to the cattle employed by each, the pattaddr receiving from his co-sharcr a proportionate amount of the State dues. If he sublets, the occupant frequently receives from his sub-tenant an en- hanced rental for the land in money or in kind. Iiidiiiddrs and non-cultivating classes usually let their lands. The non-cultivating occupant, if he be a money-lender and has purchased the occupancy right of the land, generally obtains a larger rent or share from his sub- tenant than the inamdar, who, having no cattle of his own, is obliged to let his land fur a small share. The money-lender, on the other hand, supplies his sub-tenant with funds to purchase cattle and imple- ments, and either charges interest or lets his land at rates far higher than he himself pays to the State. The latter system is very common in the Maratha Districts, where land has acquired a much higher value since the settlement, and where the non-cultivating classes, mostly comprising money-lenders, form a much higher pro- portion of the population than in Telingana.

No official returns of the prevailing rates of wages are available. Agricultural labourers and domestic servants may be taken as types of unskilled labour, and carpenters, blacksmiths, and masons as those of skilled labour. The former are paid from Rs. 30 to Rs. 36 per annum, besides receiving one meal a day, and a blanket and a pair of sandals every year. Sometimes the labourer borrows two or three years' wages from his employer for marriage expenses and undertakes to serve for a stipulated period at a reduced rate, the reduction repre- senting the amount of interest on the sum borrowed. Wages are sometimes paid partly in cash and partly in kind. To persons hired by the day, wages are generally paid in grain, but in the case of cotton- picking the labourer gets a certain proportion of the quantity picked. Village artisans are usually paid in kind, and in some few instances partly in cash and partly in grain. ^Vhen grain is dear, cash wages are substituted by the employer.

In the vicinity of towns cash wages are the rule ; and wherever cotton-ginning and pressing factories are established, or mining indus- tries developed, such as coal-mining and stone-quarrying, or railway and road construction are started, high cash wages are demanded, varying from Rs. 7 to Rs. 10 per month.

In times of scarcity wages fall considerably below the average, owing to the large number of labourers thrown out of employment. The favourable rates of assessment introduced since the last settlement have been conducive to much agricultural activity and a greater demand for labour, whereby wages have risen, and the labourer who got Rs. 30 per annum now demands Rs. 36. The same may be said of all other labourers, artisans, and domestic servants. The higher prices of food-grains have also contributed towards enhancement in the rates of wages.

In the absence of any regular record of prices, information specially collected has been embodied in Table III (p. 302). No records exist of prices prior to the construction of railways, but it is certain that prices were then much lower than now, because owing to the absence of means of transport only a small quantity of the grain pro- duced was exported. The railways have made prices of grain uniform over large tracts ; and in times of famine and scarcity in the neigh- bouring Provinces the surplus grain of the country is exported, thus causing a rise in prices. During the famines of 1897 and 1 899-1900 prices of grain were extraordinarily high, though, while grain was being imported for the relief of the affected areas, it was being largely ex- ported from the other parts of the State to Provinces where large profits were probable. During the famine of 1 899-1 900, jowar sold at 5 seers per rupee in Aurangabad, at 3^ seers in Bhir and Nanden at 4I seers in Parbhani and Osmanabad, and at 5^ seers in Bldar. In Table III the price of salt is given for Hyderabad only, the prices in the country being almost the same.

Forests

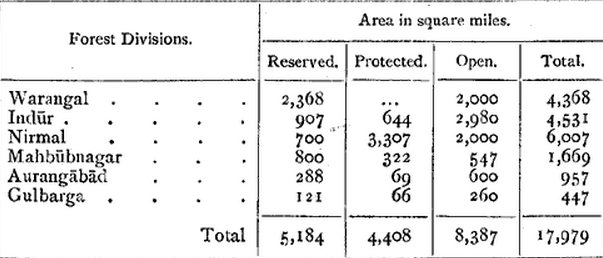

A total area of nearly 18,000 square miles is under forests, which are divided into three classes: the 'reserved' (5,184 square miles), the protected (4,408 square miles), and the open or unprotected (8,387 square miles). In the 'reserved' and protected forests, trees are under the control of the Forest depart- ment ; but in the open forests only sixteen species are reserved : namely, sandal {Sajitalum album), teak {Tedojia grandis), shisha>n {Daibergia Sissoo), ebony i^Diospyros melanoxylon), satin-wood {Chlor- oxylon Sivietenia), eppa {Hardtvickia binata), nalldmadi {Ten/iinalia tomentosd), bijdsdl {Fterocarpus Marsuptnm), batta-gunam {Stephegyne parvifolid), somi {Soymida febrifugd), dhaura or tirmani {Anogeissus latifolid), kodsha {Cleistanthus coUiniis), sandra [Acacia Caiechie), bhan- ddra {Adina cordifolia), Jiiokab {Schrebet-a swieienioides), and chinnangi {Lagerstroemia parviflora). The forests form six divisions — Warangal, Indur, Nirmal, Mahbubnagar, Aurangabad, and Gulbarga — the last two being in Marathwara, and the remainder in Telingana. Each division is under an Assistant Conservator. The management of this department is guided by the Forest Act of 1899, which empowers the Conservator to exercise full control over ' reserved ' and protected forests, and reserved species of trees in open forests. Timber is supplied to purchasers at prescribed rates, while cultivators receive free timber and fuel for agricultural implements and domestic purposes. Minor produce, such as grass, branches, and leaves, &c., is likewise granted free to the local ryots. Free grazing is also permitted, under certain restrictions. After meeting the local demand, timber of various kinds is exported to different parts of the State. Local railways and the military workshop are also supplied with timber, exploited and transported departmentally. No use is made of elephants nor are floating operations resorted to.

No special fuel and fodder reserves are maintained, but the grazing in the ' reserved ' and protected forests is regulated by the de[)ariment, and fees are collected either departmentally or tlirough contract agency. Grazing rights in the open forests are auctioned annually by the Revenue department. In years of scarcity cattle are sent to the forests, which are then thrown open to free grazing. Measures are adopted to prevent the destruction of trees for leaf fodder, and some attempts have been made to store fodder. Edible fruits, roots, and flowers are utilized during famines by the destitute and starving poor. Some of the valuable forests are protected from fire by making regular fire lines, prohibiting the carrying of inflammable materials, closing areas to grazing, and by the appointment of patrols and guards.

There are no special plantations of any economic value in the State. The following table shows the area of each class of forest in each forest division in 1901 : —

As the forest survey and demarcation have not been completed, the

areas shown above are only approximate, and it is possible that as

much as one-third of the total is really cultivated. The forests are not

equally distributed in all parts, the two Districts of Osmanabad and

Bhir having no forest at all, while the forests in Karimnagar (Elgandal),

Warangal, and Adilabad (Sirpur Tandur) occupy half the area of the

State lands. The Maratha Districts are far less wooded than the

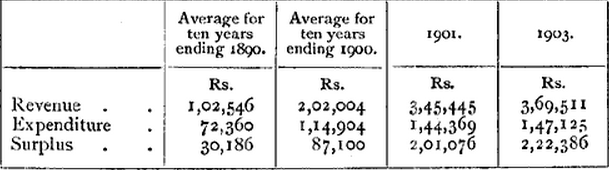

Telingana country. The figures given below show the average revenue,

expenditure, and surplus of the Forest department for a series of

years : —

The practice of shifting cultivation in forests, or pode, which was very common some years ago, is now strictly prohibited; but illicit clearances for temporary cultivation are sometimes made, and, when found out, departmental punishment is inflicted on the offenders. Several grasses are known to possess economic properties. The fibres of ma7inakopri and modian are extensively used for making ropes, for stringing cots, and for various agricultural uses. If properly treated, these might also prove suitable for manufacturing paper. Among other minor products, mahiid flowers are of importance as being generally used for distilling country liquor.

Mines and Minerals

The Hyderabad State is rich in minerals, chief among which may 1)6 mentioned the extensive coal-measures of Warangai, and the gold-mines of Lingsugur. The coal-field of Singareni was discovered by Dr. King of the Indian Geological . ,

Survey so flir back as 1872. Active operations were, however, delayed till 1886, when the Hyderabad (Deccan) Company obtained a concession, and opened the mine at Singareni, which is the only mine profitably worked at present. Four distinct seams have been discovered in the Singareni field. The first varies in thickness from 30 to 50 feet, and is composed of alternating layers of coal and carbonaceous shale, the former being of tolerably good quality and supplying a fair steam coal. The second seam, lying about 100 feet below the first, consists of shaly coal. Similarly, the third seam, which is about 30 to 40 feet below the second, consists of a hard shaly coal ; and as the coal these two contain gives 30 per cent, of ash, they have been abandoned as being of no commercial value. The fourth seam, called the King seam after its discoverer, consists of the most valuable coal, being semi-bituminous hard coal which does not coke but yields a good gas for lighting purposes. This is the seam which is now being worked. Its thickness is from 3 to 7 feet and its area about 9 square miles, and at the average thickness of 5 feet it is computed to contain no less than 47,500,000 tons of coal. The royalty paid to the State varies from 8 annas to R. i per ton. In 1896 the royalty realized was Rs. 1,25,000. The output of coal from the Singareni coal-field rose from 3,259 tons in 1887 to 144,668 in 1891, and 421,218 in 1901, and was 419,546 tons in 1904.

Tiold occurs in Lingsugur District, in the rocks of the transition series, in the Muski, Romanhal, and Sagar formations. The total area of gold-bearing rocks in this territory, as proved by the Geological Survey of India and by the prospecting operations of the Hyderabad (Deccan) Company, is about 1,240 square miles. The first band of rock lies between the Tungabhadra and Kistna rivers, and is composed essentially of a schistose l>lack hornblendic trappoid. Tliis band was actively prospected in 1896-7 by the Hyderabad (Deccan) Company, and a sul)sidiary company has since been formed to work the quartz. 'I'he average yield here, it is alleged, has been an ounce to the ton, and certain specimens have yielded as much as 20 oz. to the ton, but this is rare. Want of water for working the stamps has hampered operations, but this difficulty has been got over by the construction of an artificial reservoir. The next band is at Bomanhal, extending from the left bank of the Kistna west of Surapur for about 20 miles, and disappearing under the black cotton soil between the Bhima and the Kistna. This band is not more than 3 miles in width and is chiefly composed of hornblendic schists. Undoubted traces of old workings have been found in this locality, and from this it is inferred that this band may yet prove profitable. The third band, that of Sagar between Sagar and Surapur, is not of much importance.

Innumerable deposits of iron ore of varying qualities are widely distributed over the lateritic and granitic tracts of the State, while similar deposits have been discovered in the sandstone formations in the Godavari and Wardha valleys. In the tract situated between the Kistna and Tungabhadra rivers, hematite occurs in considerable quantities. The rocks of the Kamptee series, which are extensively developed between the Godavari and Wardha valleys, abound in hard ferruginous pebbles and clay iron ores, and are worked in the Chinnur taluk of Adilabad District. Jagtial, Nirmal, \\^arangal, Yelgarab, and other places are noted for their cast-steel cakes or disks, which were largely exported to distant parts.

From ancient times diamond mines have been worked in the alluvial deposits round about Partyal, near the Kistna, as well as in other localities in the alluvial tract of the same river. The Partyal diamond- bearing layer is about 10 to 16 inches thick, and is concealed by black cotton soil. Trials made in recent years by the Hyderabad (Deccan) Company, involving a considerable outlay, proved unsuccessful ; only stones of very small size were found, the gangue having been worked out by the old miners.

Among other minerals found in the country may be mentioned mica in the Khammamett taluk of Warangal ; fine specimens of corundum and garnets in the Paloncha taluk of the same District ; and a small deposit of graphite in the vicinity of Hasanabad in Karlmnagar (Elgandal) District. A copper lode has recently been discovered at Chintrala in Nalgonda District, which promises to be remunerative. Excellent limestone is quarried at Shahabad, between the Wadi Junction and Gulbarga on the Great Indian Peninsula Railway. These quarries are extensively worked on both sides of the line for a considerable distance. The limestone is of two colours, black and grey, the latter being the more abundant of the two, and taking a polish almost equal to marble. An extensive industry has been carried on, and the stone is not only being widely used for flooring purposes, but is exported outside the State also in large quantities for building purposes. In addition to the minerals already mentioned, red chalk and saline deposits are found.

See also

For a large number of articles about Hyderabad State, extracted from the Gazetteer of 1908 (as well as other articles on Hyderabad State) please either click the 'India' link (below, left) and go to Hyderabad State (under H) or enter ' Hyderabad State ' in the 'Search' box (top, right).

Hyderabad State, Population 1908

Hyderabad State, Agriculture 1908