Immunisation: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Contents |

Extent of under-5 population immunised

As in 2017-18

Sushmi Dey, ‘60% of under-5 kids fully immunised’, July 21, 2020: The Times of India

Around 60% of children under five years of age were fully immunised, a survey conducted by National Statistical Office (NSO) during July 2017-June 2018 shows. This includes about 59% of boys and 60% of girls across the country who had been fully immunised with all eight prescribed vaccinations — BCG, OPV- 1, 2,3, DPT- 1,2,3 and measles.

In rural India, about 58% (57% boys and 60% girls) children under five years, and about 62% (62% boys and 61% girls) children in urban India had been fully immunised.

The report also shows a decline in estimated anaemia cases during the 75th round of the survey with cases dropping to 5,96,200 from 8,80,700 during the 71st round. Proportion of persons suffering from tuberculosis has fallen to half during the latest survey to 38 per 1,00,000 persons from the earlier level of 76 per 1,00,000. The Intensified Mission Indradhanush, launched by PM Modi in 2017, aims to reach each and every child under two years of age and all pregnant women who have been left uncovered under the routine immunisation programme.

The survey shows majority of the children received vaccination from government hospitals or clinics.

About 95% of children in rural India and 86% of children in urban India had received some vaccination from government hospitals including primary and community health centres or even Anganwadi centres. Private sector catered to about 5% of children in rural India, though the percentage was slightly higher at 14% of children in urban India who received any vaccination. The government had set a target to achieve 90% immunisation coverage this year. However, the programme has suffered a big blow due to the pandemic, experts said.

Growth of immunisation

2014-18 growth> and vaccine hesitancy

From: Sushmi Dey, Vaccine refusal among top 10 threats to public health: WHO, January 24, 2019: The Times of India

Refusal or hesitation to get vaccination against deadly diseases despite availability of vaccines is seen as one of the top threats to public health, according to World Health Organisation (WHO). The UN agency recently released a list of what it considers the top 10 threats to global health for 2019, which include air pollution, obesity and antibiotic resistance.

This is the first time that vaccine hesitancy has made it to the UN agency’s list of ten biggest threats to world health. “Vaccination is one of the most cost-effective ways of avoiding disease — it currently prevents 2-3 million deaths a year, and a further 1.5 million could be avoided if global coverage of vaccination improved,” it said.

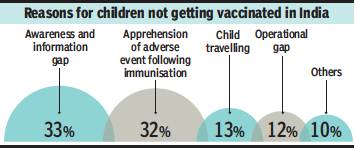

In India, lack of awareness and information coupled with apprehension of adverse event following immunisation are seen as the major reasons for children not getting vaccinated. The two factors together account for around 65% of the children not getting vaccine coverage, as per government estimates.

Between 2014 and 2018, India’s annual immunisation growth rate has risen to 4% from 1% previously.

2017-18: India behind Bangladesh, Sri Lanka

From: Rema Nagarajan, Why India lags Sri Lanka, Bangladesh in immunisation of children, August 29, 2020: The Times of India

The poor coverage of measles vaccination and later doses of basic vaccines like those for polio, diphtheria, pertussis and tetanus (DPT) are pulling down the proportion of fully immunised children which currently stands at around 60%. This indicates a poor mechanism to track children already registered in the immunisation system despite a Mother and Child Tracking System (MCTS) being in place since 2009.

A recently released NSO report on health for 2017-18 shows that from over 94% coverage for the BCG vaccine given at birth, coverage fell to just 67% for the measles vaccine, given between 9-12 months, the poorest coverage among all basic vaccines needed for a child to be counted as being fully immunised. Similarly, from 94% coverage of the oral polio vaccine’s (OPV) birth dose, the coverage went down with every subsequent dose to reach 80.6% by the third dose. The DPT vaccine coverage went from 91% coverage for the first shot given at six weeks to 78% by the third shot at 14 weeks. This meant that India’s proportion of fully immunised children remained at around 60% in 2017-18, not much different from the National Family Health survey of 2015-16, which found it to be around 62%.

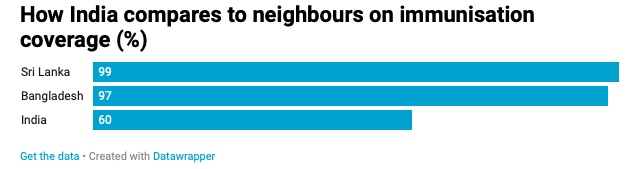

While this was a huge improvement from just 44% in 2005-06, the budget allocated for immunisation has also jumped from Rs 473 crore in 2005-06 to approximately Rs 2,000 crore allocated for the Universal Immunisation Programme (UIP) excluding shared costs such as staff salary, establishments etc. India’s immunisation coverage has remained low relative to its neighbours. In Sri Lanka 99% of children are fully immunised. In Bangladesh, the coverage for DPT-3 was 98% and for measles was 93% in 2018, according to the World Health Report 2020. In Nepal, the coverage for the third shot of DPT was 91% and that for measles was 69%. A child is considered to be fully immunised if she has received BCG, three doses of OPV, three shots of DPT vaccine and the measles vaccine. All these, if delivered on schedule, are within the child’s first year, with measles being the last.

There are booster shots and vaccines for other diseases, but they do not count for considering a child fully immunised. The central government’s Mission Indradhanush launched in December 2014 set the goal of ensuring full immunisation for children up to two years of age and pregnant women. The govt identified 201 high focus districts across 28 states that had the highest number of partially immunised and not immunised children.

Diphtheria immunisation: India lags globally

- Globally in 2019, half of children unvaccinated for DPT3 lived in just six countries: Brazil, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, India, Nigeria, and Pakistan - Despite achieving relatively high rates of immunisation coverage, India hosts 2.1 million of the under-vaccinated even with 91% coverage of a cohort of approximately 21 million surviving infants

How Covid-19 put immunisation on hold

Early in the course of the pandemic in India, several states had curtailed outreach services for immunisation and maternal health services such as ante-natal check-ups citing the need to take precautions against Covid-19 infection as TOI reported on April 2.

An estimated 26 million children are born in India each year, which is more than 71,000 babies each day. Every day of immunisation services remaining suspended thus could mean thousands missing crucial vaccines. Public health experts warned against suspension of these crucial services saying it could lead to an increase in maternal mortality and further lower the already low immunisation levels in most states.

In Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Rajasthan, Kerala and Karnataka, governments suspended outreach programmes like organising of vaccination days or door-step services. Though most states continued to offer vaccination in primary health centres, district hospitals, medical colleges etc., most health facilities, being too far away, were difficult for people to access, especially with the transport lockdown. Even in states where vaccination work was not formally suspended, additional Covid work imposed on health care workers threw it out of gear.

The impact is evident in data from the union health ministry’s Health Management Information System. For the period from April to June this year, it shows a huge fall in the number of children who got the various vaccines that are part of the Universal Immunisation Programme. For each vaccine, the number of children who got it this April-June is lower by anywhere between 12 and 22 lakh than in the same period last year. The number of fully immunised children aged 9 to 11 months is about 16 lakh less.

While all non-Covid health services have suffered during the pandemic, the setback to immunisation services could mean an outbreak of deadly diseases like measles, not just now, but well into the future. While the government might manage to vaccinate many of the children who missed a shot in this period through mop-up rounds, in many cases the window to give a particular vaccine might have closed, as many vaccines cannot be given beyond a particular period of time. According to Unicef, during the outbreak of Ebola in Congo, while 2,000 died of the epidemic outbreak, double that number died of measles as immunisation services were affected. There is apprehension in the public health community in India now that the disruption of immunisation services during Covid might similarly end up leading to greater maternal and infant mortality.

2017-18: 60% full immunisation according to NSO

Rema Nagarajan Dec 3, 2019 Times of India

From: Rema Nagarajan Dec 3, 2019 Times of India

Though well over 90% of children in India are born in an “institution” — a government or private facility — the proportion of children up to five years who have been fully immunised stagnates below 60%, according to the latest survey by the National Statistical Office. This highlights the health system’s failure to track children born in hospitals to ensure their full immunisation.

The data was revealed in an NSO survey conducted from July 2017 to June 2018 whose findings were released over the weekend. The National Family Health Survey (NFHS) done in 2015-16 showed a similar level of immunisation coverage (62%), indicating a lack of progress in the two intervening years. The data also runs counter to the government claim that the health ministry’s internal data on immunisation coverage till November 2018 showed it had touched 83% with just 2% of children getting no vaccination at all. While the data on unimmunised children ties in with the NSO survey, the data on coverage does not match.

According to the NSO, the proportion of fully immunised children was just 58.4% in rural India and 61.7% in urban areas. Moreover, in states like Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, which account for the highest number of children being born, the coverage is just 48% and 55%, respectively (see graphic).

The NSO survey covered almost 1.2 lakh households across India and the NFHS-IV conducted from January 2015 to December 2016 covered over 6 lakh households. Mission Indradhanush, meant to propel India towards 90% full immunisation coverage, was launched on December 25, 2014. Full immunisation means that children under five years should receive all eight doses of prescribed vaccines — BCG to prevent tuberculosis, three doses of oral polio vaccine (OPV), three doses of DPT or vaccine against diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis or whooping cough and measles vaccine.

NFHS-IV, which recorded almost 89% institutional births, showed that about 92% of the children received BCG vaccine given as a single dose at birth. The NSO survey, too, shows that the percentage of children who received any vaccination was over 97%. This is not surprising with over 96% institutional childbirths in urban areas and over 90% in rural areas since BCG and one OPV dose are given at birth.

As part of Mission Indradhanush, children were also given meningitis and Hepatitis B vaccines. In selected states, children were also given vaccines for Japanese encephalitis and haemophilus influenza type B. In 2016, the health ministry added more vaccines against rubella, rotavirus and an injectable polio vaccine. In 2017, the mission added pneumococcal conjugate vaccine meant to prevent pneumonia to the universal immunisation programme. While more vaccines have been added to the immunisation programme and funds deployed to purchase them, survey data indicates that coverage has been stagnant.

On October 8, 2017, Prime Minister Narendra Modi launched the Intensified Mission Indradhanush with a special drive to reach those not covered by the routine immunisation programme by focusing on select districts and cities to achieve over 90% full immunisation coverage by December 2018. Earlier, the target of the mission was to achieve this by 2020.

According to a health ministry statement in October 2017, while the increase in full immunisation coverage was 1% per year earlier, this had shot up to 6.7% per year through the first two phases of Mission Indradhanush. Considering that the mission was launched in December 2014, the NSO survey should have shown over 82% coverage. However, even in the best performing states such as Andhra Pradesh and Kerala, the coverage was just 74% and 73% respectively in the NSO survey.

2023: India’s rank in the world

July 16, 2024: The Times of India

From: July 16, 2024: The Times of India

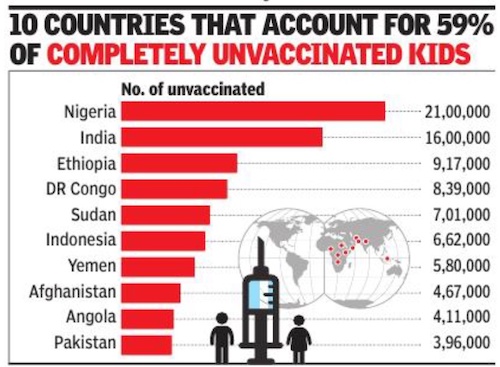

India has the second highest number of kids who did not receive any vaccine at all in 2023, 1.6 million, just after Nigeria with 2.1 million “zero dose children”, according to Unicef.

This 2023 report of WHO/Unicef estimates of National Immunisation Coverage (WUENIC) was based on member states reporting to WHO and Unicef up to July 1, 2024, the 2024 World Bank Development Indicators Online and United Nations Population Division, 2024 revision.

“The number of completely unvaccinated children (“zero-dose”) is slightly up from last year (by 600,000 from 13.9 million to 14.5 million) and is still 1.7 million higher than in 2019,” stated the report. It added that some children also “drop out”, i.e., receive a first but not a third protective dose of DTP. The total number of unand under-immunised children stands at 21 million in 2023, 2.7 million above the baseline value.

India also had the third highest number of “measles zero dose children”, 1.6 million. Nigeria with 2.8 million and Democratic Republic of Congo with 2 million children took the top spots. India was among ten countries accounting for 55% of children without measles vaccines globally.

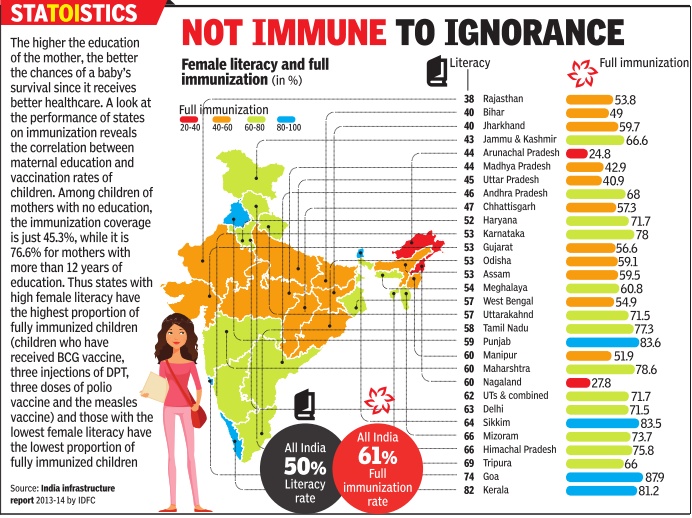

Immunisation and literacy

See graphic

Immunisation and literacy. Chart