Indus Water Treaty

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

The Times of India

Contents |

The treaty

Nehru “purchased peace with the treaty“

Indus pact once a peace gesture, Sep 27 2016 : The Times of India

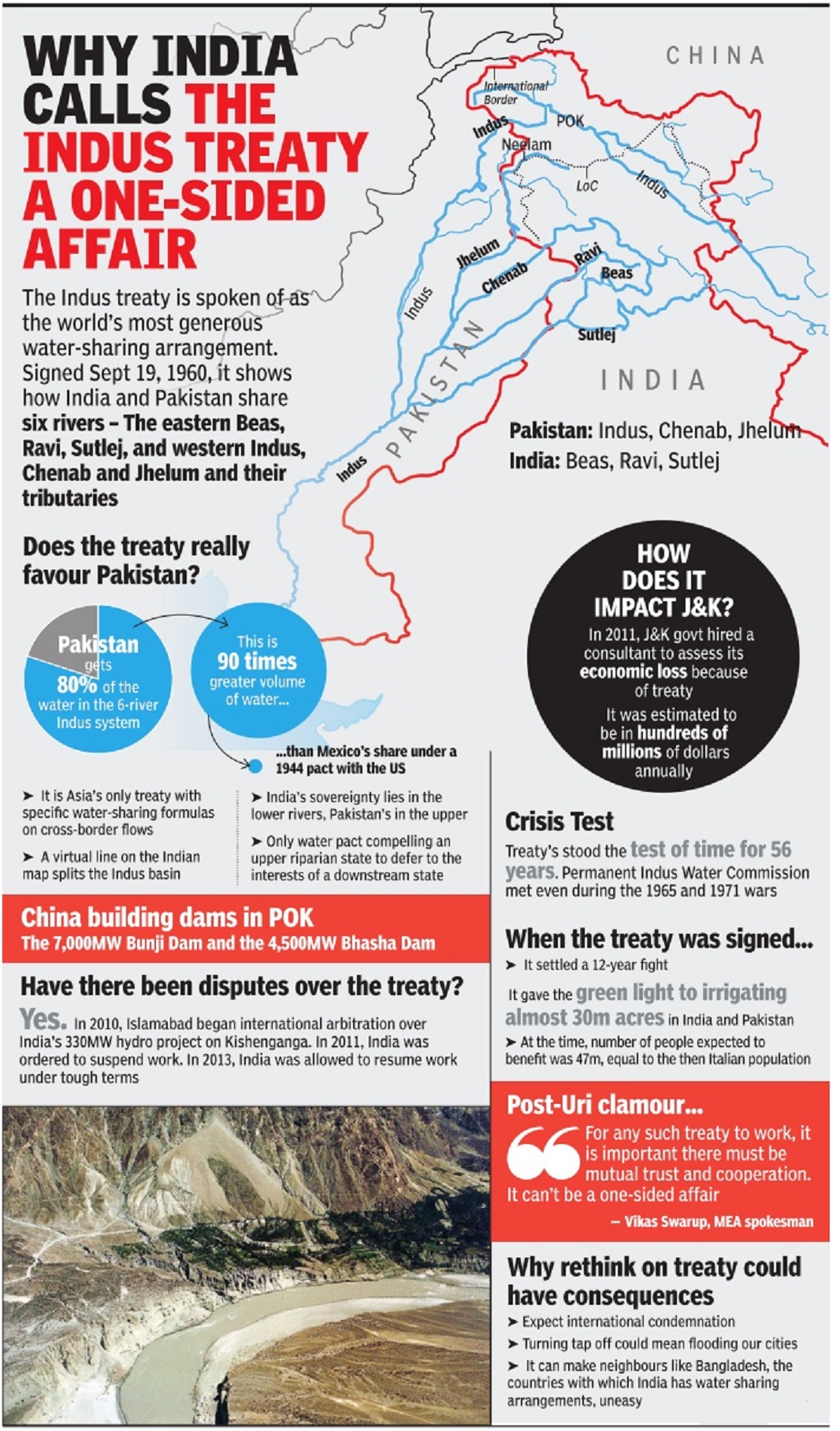

The Indus Water Treaty was once seen by India as a gesture of peace. The treaty was, in fact, believed to be an incredibly generous gesture by an upper riparian state for a lower riparian one.

Former PM Jawaharlal Nehru had even acknowledged it in Parliament and observed that India had, in fact, “purchased peace with the treaty“. The planned action against Pakistan will likely win favour from Jammu & Kashmir, which has believed for years that it had got a raw deal on the water-sharing arrangement.

In 2003, an all-party resolution in the J&K assembly had basically asked the Centre to walk out of the treaty . As per the decisions taken on Monday , India now wants to fully utilise what is due to it for agriculture, storage and hydropower.

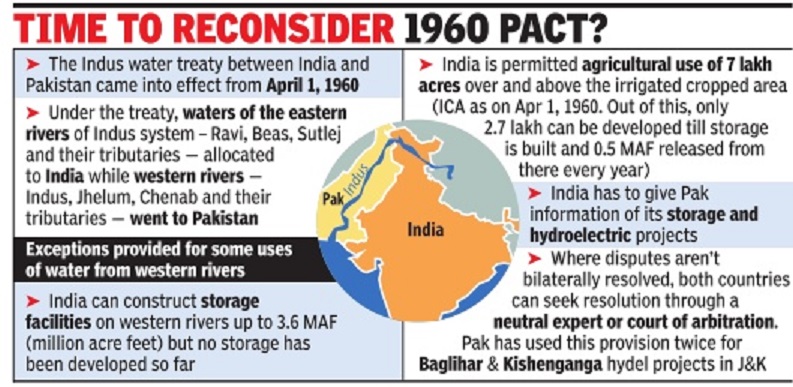

Currently , India stores no water from the western rivers, but is permitted to store 3.6 million acre feet (MAF).That, the government says, will now be done, directly impacting the amount of water available to Pakistan.

Inspection of the Chenab projects

2019: India lets Pak inspect Chenab projects

Breakthrough? India lets Pak team inspect Chenab projects, January 25, 2019: The Times of India

A three-member Pakistan delegation will visit India from January 27 for inspection of projects in the Chenab basin, official sources confirmed. The visit is mandated by the Indus Waters Treaty to allow both sides to resolve issues related to hydroelectric projects.

In what was the first official engagement between India and the Imran Khan-led government in 2018, the two sides had discussed ways to strengthen the role of the Permanent Indus Commission (PIC) for resolving matters under the 1960 treaty.

Pakistan’s water resources minister Faisal Vawda had described India’s approval to the visit as a major breakthrough. “Pakistan and India have been into Indus water treaty dispute for ages. Due to our continued efforts there’s a major breakthrough that India has finally agreed to our request for inspection of Indian projects in Chenab basin,” he had tweeted.

The two countries are currently involved in technical discussions on implementation of various hydroelectric projects under the provisions of the Indus Waters Treaty including Pakal Dul (1,000 MW) and Lower Kalnai (48 MW) in the state of Jammu & Kashmir. Both the countries had in the last meeting agreed to undertake the treaty mandated tours of both the Indus Commissioners in the Indus basin on both sides.

Pakistan media reports had then said that India had invited Pakistani experts to visit the sites of the Pakal Dul and Lower Kalnai hydropower projects on the Chenab river next month to address Islamabad’s concerns over the construction of the projects.

During the talks, India was said to have rejected Pakistan’s objections to the construction work.

Kishenganga, Ratle

2025: World Bank’s neutral expert accept’s India’s position

January 22, 2025: The Times of India

India welcomed the ruling by the World Bank-appointed neutral expert that said differences between India and Pakistan over the Kishenganga and Ratle hydroelectric power projects in J&K fall within his competence under the Indus Waters Treaty. The govt sees this as a vindication of its stand and interpretation of the treaty as it does not recognise or participate in the parallel and “illegally constituted” court of arbitration proceedings being carried out at Pakistan’s request.

In a statement on the neutral expert’s decision, govt said it remains in touch with Pakistan for the modification and review of the IWT. India had last year cited cross-border terror as one of the reasons for seeking a review of the treaty.

One-sided, against India

India’s options vis-à-vis Pakistan

The Times of India

The Times of India

The Times of India

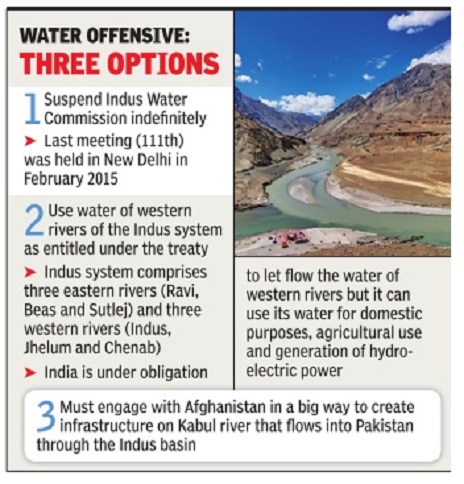

Amid clamour for a rethink on the Indus Waters Treaty with Pakistan in the wake of the Uri terror strike, experts have argued that short of the “extreme“ step of abrogation, India has other options like use of water of western rivers of the Indus system or suspension of the meetings of Indus Water Commission to put pressure on its neighbour.

The experts point out that these available options would be enough to send signal to Pakistan about the leverage India has over the entire river system without actually scrapping the treaty or violating any of its clauses.

“Abrogation of treaty is neither practical nor desirable. India can rather go for the extreme option of suspending the meeting of the Commission. However, the more realistic option would be to use water of the western rivers of the Indus system, which is well within the framework of the treaty ,“ said Uttam Sinha of the Institute of Defence Studies and Analyses (IDSA).

Under the Indus Water Treaty , signed between the two countries in 1960, water of eastern rivers (Ravi, Beas and Sutlej) are allocated to India while the country is under obligation to let flow the water of the western rivers (Indus, Jhelum and Chenab) to Pakistan.

India can, however, use the water from the western rivers for its domestic purposes, irrigation and generating hydro-electric power.

“We should use this option legitimately . It is India's right under the treaty . Pakistan cannot challenge this as it knows that India can use water of western rivers under the specified clauses of the treaty. If India exercises this option, it would be enough to put Pakistan under extreme pressure,“ Sinha told TOI on Friday .

River expert and environmentalist Himanshu Thakkar of the South Asia Network on Dams, Rivers and People (SANDRP) agrees with such an option. India has been permitted to construct storage of water on western rivers up to 3.6 million acre feet (MAF) for various purposes, but the country has, so far, not developed any storage facility .

Thakkar said, “We have never exercised our rights under the treaty as we have not created infrastructure on our side to use water of western rivers. We must, therefore, concentrate on building barrages and other storage facilities to use the water.“

Thakkar too found the idea of abrogating the treaty impractical. He said, “It will not solve any purpose. It won't help India militarily . It will, instead, damage India's credibility at international forums. We have treaties and water-sharing arrangements with other neighbours like Nepal, Bhutan, Bangladesh and China. Abrogation of treaty will certainly not send the right signal.“

The experts also pointed at the third option where India can align itself with Afghanistan by helping it create infrastructure on the Kabil river that flows into Pakistan through the Indus basin.

Sinha said, “Though India has been engaged with Afghanistan, there is a need to go for it in a big way in our strategic interest. This option will also exert pressure on Pakistan.“

A one-sided treaty and benefits to Pakistan: Till 2017

Brahma Chellaney, Shed The Indus Albatross, Mar 20 2017: The Times of India

Indus Waters Treaty offers one-sided benefits to Pakistan, World Bank too is partisan

At a time when India is haunted by a deepening water crisis, the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT) hangs like the proverbial albatross from its neck. In 1960, in the naïve hope that water largesse would yield peace, India entered into a treaty that gave away the Indus system's largest rivers as gifts to Pakistan. Since then that congenitally hostile neighbour, while drawing the full benefits from the treaty, has waged overt or covert aggression almost continuously and is now using the IWT itself as a stick to beat India with, including by contriving water disputes and internationalising them.

A partisan World Bank, meanwhile, has compounded matters further.Breaching IWT's terms under which an arbitral tribunal cannot be established while the parties' disagreement “is being dealt with by a neutral expert“, the Bank proceeded in November to appoint both a court of arbitration (as demanded by Pakistan) and a neutral expert (as suggested by India). It did so while admitting that the two concurrent processes could make the treaty “unworkable over time“.

World Bank partisanship, however, is not new: IWT was the product of the Bank's activism, with US government support, in making India embrace an unparalleled treaty that parcelled out the largest three of the six rivers to Pakistan and made the Bank effectively a guarantor in the treaty's initial phase. With much of its meat in its voluminous annexes this is an exhaustive, book-length treaty with a patently neo-colonial structure that limits India's sovereignty to the basin of the three smaller rivers.

The Bank's recent decision was made more bizarre by the fact that while the treaty explicitly permits either party to seek a neutral expert's appointment, it specifies no such unilateral right for a court of arbitration. In 2010, such an arbitral tribunal was appointed with both parties' consent. The neutral expert, however, is empowered to refer the parties' disagreement, if need be, to a court of arbitration.

The uproar that followed the World Bank's initiation of the dual processes forced it to “pause“, but not terminate, its legally untenable decision. Stuck with a mess of its own making, it is now prodding India to bail it out by compromising with Pakistan over the two moderate-sized Indian hydropower projects. But what Pakistan wants are design changes of the type it enforced years ago in the Salal project, resulting in that plant silting up. It is threatening to target other Indian projects as well.

Yet Indian policy appears adrift.Indeed, India is backsliding even on its tentative moves to deter Pakistani terrorism. For example, after last September's Uri attack, it suspended the Permanent Indus Commission (PIC) with Pakistan. Now the suspension has been lifted, allowing the PIC to meet in the aftermath of the state elections.

In truth the suspension was just a charade, with the PIC missing no meeting. Prime Minister Narendra Modi reversed course in time for PIC, which meets at least once every financial year, to meet before the current year ended on March 31in order to prepare its annual report by the treaty-stipulated June 1deadline. But while the suspension was widely publicised for political ends, the reversal happened quietly.

Much of the media also fell for another charade that Modi sought to play to the hilt in Punjab elections: He promised to end Punjab's water stress by utilising India's full IWT-allocated share of the waters. His government, however, has initiated not a single new project to correct India's abysmal failure to tap its meagre 19.48% share of the Indus waters.

Instead, Modi has engaged in little more than eyewash: He has appointed a committee of secretaries, not to find ways to fashion the Indus card to reform Pakistan's conduct, but farcically to examine India's own rights under IWT over 56 years after it was signed. The answer to India's serious under-utilisation of its share, which has resulted in Pakistan getting more than 10 billion cubic metres (BCM) yearly in bonus waters on top of its staggering 167.2 BCM allocation, is not a bureaucratic rigmarole but political direction to speedily build storage and other structures.

Despite Modi's declaration that “blood and water cannot flow together“, India is reluctant to hold Pakistan to account by linking IWT's future to that renegade state's cessation of its unconventional war. It is past time India shed its reticence.

Pakistan's interest lies in sustaining a unique treaty that incorporates water generosity to the lower riparian on a scale unmatched by any other pact in the world. Yet it is undermining its own interest by dredging up disputes with India and running down IWT as ineffective for resolving them. By insisting that India must not ask what it is getting in return but bear only IWT's burdens, even as it suffers Pakistan's proxy war, Islamabad itself highlights the treaty's one-sided character.

In effect, Pakistan is offering India a significant opening to remake the terms of the Indus engagement. This is an opportunity that India should not let go. The Indus potentially represents the most potent instrument in India's arsenal more powerful than the nuclear option, which essentially is for deterrence.

1960-2025: Was the Treaty fair to India?

Since it was signed in 1960, what has the Indus Waters Treaty meant for India?

The Indus Waters Treaty was a product of the context in which it was signed. A lot has changed since then, not just politically, but hydro-geomorphologically and in terms of population growth and irrigation use. In all fairness, the treaty needs to be renegotiated keeping the current realities in mind.

Under the treaty, Pakistan got a higher volume of water. The average annual flow of water in the ‘western rivers’ (135.6 million acre feet) is more than four times that of the eastern rivers (32.6 maf). But two things are important to note here. India needed the exclusive use of the waters of the eastern rivers, which the treaty secured for us. India has since built dams and other water projects on these rivers, including the Bhakra Nangal dam and the Rajasthan canal project now called the Indira Gandhi Canal, which have helped irrigate Punjab, Haryana, and Rajasthan.

In return, Pakistan got a much larger portion of the flow of water from the three western rivers but India was entitled to certain use on these rivers such as domestic use, non-consumptive use, agriculture use and generation of hydro-electric power. This we have not fully utilised. Also, India has the right to create water storage capacity of up to 3.6 million acre-feet (MAF) on the western rivers. A capacity of only about .7 MAF on Salal and Baglihar dams havebeen achieved. With the Pakaldul dam nearing completition, the storage capacity is set to inch up to .8 maf.

It helps to remember that the treaty was negotiated by civil engineers and not politicians and diplomats. So it took a pragmatic and utilitarian view of the Indus Basin. The system of rivers was apportioned or divided into eastern and western rivers and not volumetric allocations. If it was based on volumes, it would have required negotiating six separate agreements, a task that would have never been accomplished.

Yashee is an Assistant Editor with the indianexpress.com, where she is a member of the Explained team. She is a journalist with over 10 years of experience, starting her career with the Mumbai edition of Hindustan Times. She has also worked with India Today, where she wrote opinion and analysis pieces for DailyO. Her articles break down complex issues for readers with context and insight. Yashee has a Bachelor's Degree in English Literature from Presidency College, Kolkata, and a postgraduate diploma in journalism from Asian College of Journalism, Chennai, one of the premier media institutes in the country

India has set in motion its ambitious plan to utilise its share of water from western tributaries of the Indus, a decision driven by India-Pakistan geopolitics, which may see work begin on a major hydel project on the Chenab early next year.

It is a long haul to implement PM Narendra Modi's September 27 decision to review water use within the ambit of the Indus Water Treaty (IWT) with Pakistan, but the government has prioritised three hydel projects on Chenab and its tributary --Sawalkot (1,856 MW), Pakal Dul (1,000 MW) and Bursar (800 MW) --in a time-bound manner.

Building infrastructure on Indus, Chenab, Jhelum and their tributaries is a huge task but the short-listed projects are intended to express India's political will and preparedness to respond to Pakistan's use of terrorism against India with every option at its command including a new preparedness to use all possible leverage points.

“The Centre has constantly been in touch with Jammu & Kashmir government for all necessary ground work. Execution of Sa walkot project is expected to start early next year. The under-construction Pakal Dul project has already received an impetus after the government displayed an urgency to complete it on time,“ said an official.

The Sawalkot project envisages a 193-meter-high dam on Chenab for generating 1,856 MW. It will be constructed in two phases. Since 629 families consisting of 4,400 individuals are likely to be displaced, the state government has been working on a proper rehabilitation plan before actual work begins.

The Bursar project will, however, take time before it gets clearances. “Since had initially termed it an unviable project on certain grounds, there is need for proper study before the government goes ahead with it. The project may be tweaked to make it viable as it is now our priority area,“ said the official.

As previous cost and viability calculations are revised in view of the political imperative, India could be looking to use as much of Indus water as it can. “Maximising use of water must be priority. It is good that the government has sincerely moved to execute pending pro jects to legitimately use its share of water within IWT.This is the most realistic option well within the framework of the treaty,“ said Uttam Sinha of the Institute of Defence Studies and Analyses (IDSA).

Towards this end, speeding up pending hydro-power projects is only one component of what India can do to utilise its share of water under the IWT. Under the 1960 treaty, India is permitted to construct storage capacities on the western rivers up to 3.6 million acre feet (MAF) for various purpo se including domestic use.India has, so far, not developed any storage facility or tapped its full quota of water for irrigation.

Referring to the World Bank's recent decision to set up a Court of Arbitration (CoA) to settle disputes relating to Kishanganga and Ratle hydro projects on Pakistan's demand, Sinha said India should forcefully tell the Bank to factor in technological changes and new knowledge while looking at the implementation of ongoing projects.

India has second thoughts

September 2016- 2023 Jan

Sanjay Datta, January 28, 2023: The Times of India

NEW DELHI: A hint of the Narendra Modi government's rethink on the Indus water treaty came for the first time in September 2016. "Blood and water cannot flow together," the Prime Minister had told officials attending a treaty review meeting that took place 11 days after Pakistan backed terrorists attacked the Indian Army base at Uri in Jammu, killing 18 soldiers.

Less than two years later, the Prime Minister in May 2018 inaugurated the 330 MW (megawatt) Kishanganga hydel project at Bandipore and laid the foundation stone for the 1,000 MW Pakal-Dul plant at Kishtwar in Jammu & Kashmir.

Indeed, two other large hydel projects – the 1,856 MW Sawalkote and 800 MW Bursar – were also fast-tracked soon after the September 2016 treaty review meeting mentioned earlier.

Situated on two tributaries of Chenab – Kishanganga and Marusudar, respectively – the projects indicated the government was ready to respond to Islamabad's use of terror against India with every option, including denying Pakistan liberal flow of Indus water in excess of the 1960 treaty’s provisions.

The launch of the Pakal-Dul project, which has been hanging fire for a decade, underlined the Modi government’s intent to fast-track infrastructure on the Indus water system, to maximise India’s water use within the treaty’s ambit. This includes building hydel projects on western tributaries of Indus such as Chenab and Jhelum as well as streams feeding them.

Since then, the Centre has fast-tracked a slew of stalled hydel projects aggregating nearly 4,000 MW capacity in Jammu & Kashmir, with PM Modi in April last year laying the foundation stones of 850 MW Ratle and 540 MW Kwar hydroelectric projects on Chenab in Kishtwar.

A 2011 report by the US Senate Committee on Foreign Relations had said India could use these projects as a way to control Pakistan’s supply from the Indus, considered its jugular. “The cumulative effect of these projects could give India the ability to store enough water to limit the supply to Pakistan at crucial moments in the growing season,” the report had said.

Clearly, speeding up pending hydel projects and storage infrastructure is a key component of India’s Indus strategy as the treaty in its present form allows India to build storage capacities on the western rivers upto 3.6 million acre feet (MAF) for various purposes, including domestic use.

YEAR-WISE DEVELOPMENTS

2025: After surviving three wars, Indus Waters Treaty finally gets the axe

Vishwa Mohan, April 24, 2025: The Times of India

New Delhi : India’s decision to suspend Indus Waters Treaty (IWT) is one of the most stringent actions against Pakistan as the 1960 treaty had survived three wars — 1965, 1971 and Kargil — and multiple terror attacks, largely on humanitarian grounds despite the treaty being in focus as a key tool to punish Islamabad for its nefarious acts.

The decision means water flow from the western rivers — Indus, Jhelum and Chenab and their tributaries —will be stopped immediately from wherever it is regulated through dams or whatever little structures India has on these rivers. Though the flow from natural channels will continue, India’s move will impact irrigation and drinking water supply to some extent in two of the four provinces of Pakistan during the peak of summer when it needs water the most.

Subsequently, India will have to increase its water storage capacity and work on Kishanganga and Ratle hydro-electric projects. Only then will India have more control over water in the long run. The Permanent Court of Arbitration in the Hague, Netherlands has already endorsed the Indian govt’s stand of resolving the dispute on design and water usage of the projects through a World Bank- appointed neutral expert.

IWT was signed between India and Pakistan for sharing of waters of the Indus Basin. Under the treaty, the total waters of the eastern rivers — Sutlej, Beas and Ravi — was allocated to India for unrestricted use while the waters of western rivers — Indus, Jhelum and Chenab — was allocated largely to Pakistan.

India is, however, permitted to use the water of western rivers for domestic use, irrigation and generation of hydro-electric power. But India has not been fully utilising its legal share due to lack of storage capacity.

Though India has right to create water storage capacity up to 3.6 million acre-feet on western rivers as per IWT, not enough storage capacity has been created. Besides, out of estimated power potential of 20,000 MW, which can be harnessed from power projects on western rivers, only 3,482 MW capacity has been constructed.

See also

Water Resources: India (ministry data)

Pakistan- India relations: water

Indus Water Treaty