Ladakh

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Ladakh

This article has been extracted from THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908. OXFORD, AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. |

Note: National, provincial and district boundaries have changed considerably since 1908. Typically, old states, ‘divisions’ and districts have been broken into smaller units, and many tahsils upgraded to districts. Some units have since been renamed. Therefore, this article is being posted mainly for its historical value.

The most westerly province of the high mountainous

land spoken of as Tibet is called Ladakh or Ladag. It is now politi-

cally a division of the Kashmir State, lying between the Himalayas

and the Kuenlun mountains, and between Baltistan and Chinese

Tibet. The Karakoram range forms the northern boundary as far

east as the Karakorani pass. The country is known t(j educated

Tibetans by other names — Mangyal, Nearis, Maryul.

Physical aspects

Ladakh is one of the most elevated regions of the earth, its sparse cultivation ranging from 9,000 to 14,000 feet. The scanty population is found in scattered and secluded valleys, where along the river banks and on alluvial plateaux crops are raised by irrigation. Central Ladakh, which lies in the Indus valley, is the most important division of the country.

To the north is Nubra, consisting of the valley of the Nubra river and a portion of the valley of the Shyok. The great floods of the Indus, caused by the descent of glaciers across its stream and that of the Shyok, and the consequent damming back of the Nubra river have caused great destruction to riverain lands, once cultivated but now wastes of granitic sand. Here the fields are fenced to guard the crops from the ponies of traders on their way to Yarkand. The south is the Rupshu country with its great lakes. Rupshu Lake covers an area of 60 to 70 square miles. Tsomoriri is 15 miles in length, and lies at an elevation of 14,900 feet. The lakes are land-locked and brackish. East of Central Ladakh is the lake of Pangkong, and in its neighbour- hood crops of beardless barley and peas are raised at an elevation of 14,000 feet. South-west is the country of Zaskar, with a very severe climate chilled by the lofty snow ranges.

The flora of Ladakh is scanty, and timber and fuel are the most pressing wants of the people. The burtse {Enrotid) is a low-growing bush which gives a fair fuel ; and in the high valleys the dama, a kind of furze, is burnt. On some hill-sides the pencil cedar {padam) occurs, and in occasional ravines the wild willow is found. Arboriculture used to be discountenanced under the Gialpos, on the ground that trees deprived the land of fertility.

On the plains up to 17,000 feet wild asses or kiang {Equiis heini- onus), antelope [Fantholops hodgso/ii), wild yak {Bos grunniens), ibex {Capra sibiricd), and several kinds of wild sheep {Ovh hodgsoni, O. vignei, and O. nahurd) are found ; and the higher hill slopes up to 19,000 feet contain hares and marmots, the beautiful snow leopard {Felis imcid), and the lynx {F. lynx). Knight, in Where Three Empires meet, remarks : —

'Not only man, but also all creatures under his domination— horses, sheep, goats, fowls — are diminutive here, whereas the wild animals on the high mountains are of gigantic size.'

Drew counted as many as 300 kiang in a day's march. In outward appearance the kiang is like a mule, brown in colour with white under the belly, a dark stripe down the back, but no cross on the shoulder. One kiang shot by Drew was 54 inches in height. The flesh is rather like beef. They are common on the Changchenmo, and are met with in many parts of Ladakh, where their curiosity often disconcerts sports- men by alarming game worth shooting. A curious fact in the fauna of Ladakh is the absence of birds in the higher parts of the country. An occasional raven is the only bird to be seen.

The climate is very dry and healthy. Rainfall is extremely slight, but fine dry flaked snow is frequent, and sometimes the fall is heavy. There is a remarkable absence of thunder and lightning. The air is invigorating, and all travellers notice the extraordinary extremes of cold and heat. In Rupshu the thermometer falls as low as 9° in September. The minimum temperature of the month is 23'5°, and the mean tem- perature 43°. As Knight remarks : —

'So thin and devoid of moisture is the atmosphere that the varia- tions of temperature are extreme, and rocks exposed to the sun's rays may be too hot to lay the hand upon, at the same time that it is freez- ing in the shade. To be suffering from heat on one side of one's body, while painfully cold on the other, is no uncommon sensation here.'

History

See Ladakh: history

Population

Leh (population, 2,079) is the only place of importance in Ladakh, and there are besides 463 villages. With the exception of one village of Shiah IMusalmans in Chhachkot, and of the Arguns or half- breeds, practically the whole population, excluding Population.

the town of Leh, is Buddhist. Ihe people style themselves Bhots. According to the last Census, there are now 30,216 Buddhists living in Ladakh. They have the Mongolian cast of features, and are strong and well made, ugly, but cheerful and good- tempered. If they do quarrel over their barley beer (chang), no bad blood remains afterwards. They are very truthful and honest, and it is said that in court the accused or defendant will almost invariably admit his guilt or acknowledge the justice of the claim.

There are five main castes {riks) : the Rgrial riks, or ryot caste ; the Trangzey riks^ or priestly caste ; the Rjey ^riks, or high officials ; the Hmang riks, or lower officials and agricultural classes ; and the Tolbay riks, or artificers and musicians. This last caste, also known as Bern, is considered inferior.

The Ladakhis may be divided into the Champas or nomads, who follow pastoral pursuits on the upland valleys, too high for cultivation ; and the Ladakhis proper, who have settled in the valley and the side valleys of the Indus, cultivating with great care every patch of cul- tivable ground. These two classes do not, as a rule, intermarry, and Champas rarely furnish recruits to the monasteries. The Ladakhis are mostly engaged in agriculture, and in spite of the smallness of their holdings they are fairly prosperous. Their great wants are fuel and timber. For fuel they use cow-dung and the bush known as burtse. Their only timber trees are the scattered and scanty willows and poplars which grow along the watercourses.

There can be little doubt that the modest prosperity of the Ladakhis, in contrast to the universal poverty of Baltistan, is due to the practice of polyandry, which acts as a check on population. Whereas the Baltis, used to the extremes of temperature, are able to seek employ- ment in hot countries, the Ladakhis would die if they were long away from their peculiar climate. In a family where there were many brothers, the younger ones could neither marry nor go abroad for their living. When the eldest son marries, he takes possession of the Httle estate, making some provision for his parents and unmarried sisters. The eldest son has to support the two brothers next him in age, who share his wife. The children of the marriage regard all three husbands as father. If there be more than two younger brothers, they must go out as Lamas to a monastery, or as coolies ; or, if he be fortunate, a younger son can marry an heiress, and become a Magpa. (If there is no son in a family the daughter inherits, and can choose her own husband, and dismiss him at will with a small customary present. The Magpa husband is thus always on probation, as the heiress can discard him without any excuse or ceremony of divorce.) When the eldest dies or becomes a Lama, the next brother takes his place. But the wife, provided there are no children, can get rid of his brothers. She ties her finger by a thread to the finger of her deceased husband. The thread is broken, and she is divorced from the corpse and the surviving brothers. The woman in Ladakh has great liberty and power. She can, if she likes, add to the number of her husbands. Drew, who had a very intimate knowledge of Ladakh, thinks that polyandry has had a bad effect on the women, making them overbold and shameless. But others, who are equally entitled to form an opinion, consider this an unfair criticism.

In the town of Leh are many families of half-castes known as Arguns, the results of the union between I^dakhi women and Kash- miris, Turk! caravan-drivers, and Dogras. The Dogra children were known as Ghulamzadas, and were bondmen to the State. The half-castes of Leh are no more unsatisfactory in Tibet than else- where, and many travellers have testified to the good qualities of the Argun.

The monasteries {gompa) play an important part in the life of the Ladakhis. Nearly every village has its monastery, generally built in a high place difficult of access. At the entrance are prayer cylinders, sometimes worked by water-power, and inside a courtyard is a lofty square chamber in which the images and instruments of worship are kept. No women may enter this chamber. Every large family sends one of its sons to the monastery as a Lama. He goes young as a pupil, and finishes his studies at Lhasa. In a monastery there are two head Lamas : one attends to spiritual, the other to temporal matters. The latter is known as the Chagzot or Nupa.

He looks after the revenue of the lands which have been granted to the monastery, carries on a trade of barter with the people, and super- vises the alms given by the villagers. He also enters into money- lending and grain transactions with the surrounding villages. Many monasteries receive subsidies from Lhasa. The Lamas wear a woollen gown dyed either red or yellow. The red Lamas predominate in Ladakh. The red sect known as Drukpas are not supposed to marry while in the priesthood. Nunneries are frequently found near the monasteries of both sects, but the Chotnos, or nuns of the yellow sect, have a higher character than those of the red sisterhood. About a sixth of the population of Ladakh is absorbed in religious houses. The Lamas are popular in the country, are hospitable to travellers, and are always ready to help the villagers.

There are two missions at Leh — the Moravian and the Roman Catholic. The Moravian Mission is an old and excellent institu- tion, much appreciated by the people for its charity and devotion in times of sickness. The mission has a little hospital, whither the Ladakhis, whose eyes suffer from the dustiness of the air and the confined life in the winter, flock in great numbers.

Agriculture

The soil is sandy, and requires careful manuring, and nothing can be raised without irrigation. The chief crops are wheat, barley, beard- less barley, peas, rapeseed, and beans in the spring if buckwheat, millets, and turnips in the autumn. Lucerne grass is grown for fodder. The surface soil is frequently renovated by top-dressings of earth brought from the hill-sides, and it is a common practice to sprinkle earth on the snow in order to expedite its disappearance. Fruit and wood are scarce, except in villages situated on the lower reaches of the Indus.

Beardless barley {grim) is the most useful crop, and can be grown at very high elevations (15,000 feet). In the middle of Ladakh the crop is secure if there be sut^cient w-ater ; and in the lower villages the soil is cropped twice a year, as there is ample sunshine ; but in Zaskar, which is near the high snowy range, the crops often fail for lack of sun- warmth. Ploughing is chiefly done by the hybrid of the j'ak bull and the common cow, known as zo (male) or zomo (female). This animal is also used for transport purposes. Grazing is limited, and conse- quently the number of live-stock is not large ; but there are a fair number of ponies, those from Zaskar being famous. The food of the Ladakhis is the meal of grim, made into a broth and drunk warm, or else into a dough and eaten with butter-milk. The Ladakhis have no prejudices, and will eat anything they can get. .

Borax is produced in Rupshu, and salt is found. About 1,436 maunds of borax are extracted annually, but the industry is profitable neither to the people nor to the State. In former days sulphur, salt- petre, and iron were manufactured in factories at Leh, but the scarcity of fuel has now rendered these industries impossible.

Practically the only manufacture is that of woollen cloth, known as pattu and pashmhia.

Trade and Communication

The people trade in agricultural products with the communications Champas of Tibet and with Skardu. Salt is largely exported to Skardu, and in a less degree to Kashmir, being exchanged for grain, apricots, tobacco, madder, and ponies. The chief commerce is the Central Asian trade between Yarkand and India. Ladakh is in the charge of a Wazir Wazarat, who is responsible for Pakistan and the three tahsil of Ladakh, Kargil, and Skardu. His duties are light. There is little crime and scarcely any litigation. 1he chief cases are disputes regard- ing trees, or complaints that one villager has stolen the surface soil of another. No police force is maintained, but a small garrison of State troops is quartered in the fort at Leh, a building with mud walls. The Wazir Wazarat and his establishment cost the State Rs. 9,166 per annum. One of the chief functions of the Wazir is the supervision of the Central Asian trade which passes through Leh. For this purpose he is ex-officio Joint Commissioner, associated with a British officer appointed by the Indian Government. Each subdivision of Ladakh is in the charge of a kdrddr, who is a Bhot. His chief duties are to see that all reasonable assistance is rendered to the Central Asian traders and travellers. For this purpose the villages of each kdrddri are made responsible for furnishing baggage animals and supplies in turn, and according to the capacity of each village to the stages situated within the limits of the karddri. This is known as the reis system. Primary schools are maintained at Skardu and at Leh.

The land revenue system in the past has been of a very arbitrary description, the basis of assessment being the holding or the house. The size of the holding or the quality of the soil receives little con- sideration. Taken collectively, it has perhaps not been heavy, though the rates are considerably higher than those now applied in Baltistan ; but its incidence has been unfair, oppressive to the poor, and very easy to the rich. A redistribution of the old assessments on a more equi- table principle, and a summary revision where the assessments were obviously too high or unnecessarily light, have recently been carried out by a British official lent to the State. The greater part of the revenue is paid in cash, but some is taken in grain and wood, which are necessary for the supply of the Central Asian traders. The grain is stored at convenient places on the caravan route in the charge of officials who sell to the traders. But for this system trade would be hampered ; for after leaving the Nubra valley and crossing the Karakoram range no fodder is available on the Yarkand road till ShahiduUah in Chinese territory is reached, and grain for feeding animals must be carried from Nubra. The strain of forced labour is heavy in Ladakh. Not only is unpaid transport taken for political missions, assistance to the trade route, &c., but several monasteries are allowed to impress unpaid labour for trading purposes.

Agricultural advances, chiefly seed-grain, are made for the most part not by the State, but by the monasteries, and the poorer classes are heavily in debt to the religious institutions. These are not harsh creditors. When the debtor is hopelessly involved, the monastery takes possession of half of his land for a period of three years. If the debt is not liquidated within three years, the land is restored to the debtor and the debt written off. 'J'he monastery will never sue a debtor, nor is land ever permanently alienated for debt.

Society, mindset

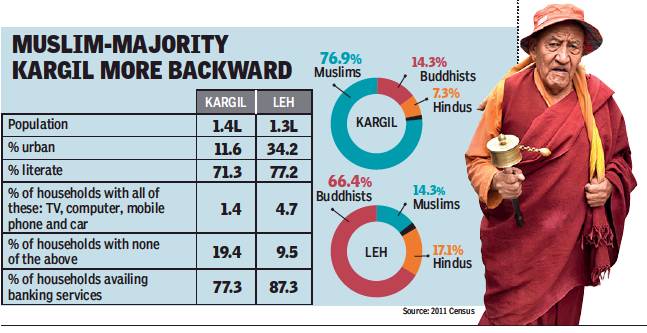

Kargil vis-à-vis Leh

2019 Aug: After the UT status

August 18, 2019: The Times of India

From: August 18, 2019: The Times of India

From: August 18, 2019: The Times of India

From: August 18, 2019: The Times of India

It is the day after Eid but celebrations are in the shadow of Section 144. Many shops are shut, and even though people throng the main market near Imam Khomeini chowk, it is in a hurry to buy medicines, vegetables and essentials. The odd bunch of young girls stops to share an ice-cream or a soft drink despite the army patrol.

Chatting with mostly reluctant locals reveals an anger and frustration simmering underneath. Some, like Akhtar Hussain, a student of International Relations in Delhi’s Jamia Millia Islamia University, did come out on the streets to protest. “I am studying in Delhi and I have always argued with my Kashmiri friends in favour of India. Jo yakeen tha woh khatam ho gaya (The faith in Indian democracy is finished),” he says. Hussain says that their immediate future too appears to be in shadow. “How can we compete for exams and jobs with people who have studied in Delhi and Mumbai,” he asks.

The absence of yakeen has hit people in many ways. It is in the absence of daily necessities like onions that have been missing from the market because of the highway blockade. It is in the absence of internet and erratic phone connectivity making it difficult to even wish Eid Mubarak to a loved one. It is the absence of being heard. As 23-year-old Mohammed Salim says, “Our view has not been taken. Why has the internet been shut down? Where is democracy when it comes to us?”

Activist Sajjad Hussain, who recently fought and lost the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, says the abrupt decision to declare Kargil a part of Ladakh union territory without taking political leaders into confidence has broken the trust between the Centre and the people. “Even at the height of militancy we have never given the call for azaadi. We have always been in favour of India yet we have been treated so badly,” he says.

Former minister in the National Conference government, Qamar Ali Akhoon, points out that ties go beyond geographical borders. “We have a historical connection with J&K. How can we be cut off from them now? We are landlocked and our only connection to the rest of India is through the highway that passes through J&K,” he says. Just three kms from the LoC is Hardas village that lies along the apricot belt. Syed Rizvi, who lives there and has family across the mountain in Pakistan’s Gilgit-Baltistan, says he used to scoff at his family for their lack of political representation. “With this decision I have become voiceless,” he says, “I felt safer during the 1999 Kargil conflict when my village was being shelled than I feel now.” Leh: Chhang Dolma’s wizened face lights up when she is asked about Ladakh’s UT status. Dolma, a farmer from Katpa village, who sells fresh salad leaves, carrots, and cauliflower in Leh’s main market, has sat on several agitations for it. “Dus baar (Ten times),” she says when asked how many agitations she has participated in. “Dil bahut khush hua (I was very happy),” she says.

Like her, most Ladakhis continue to support the Centre’s decision, but doubt about its implications have begun to creep in. While some feel that cutting Ladakh off from the Valley’s politics will bring it muchneeded attention, there are others who are anxious that a deluge of outsiders might ruin this ecologically sensitive region.

The older generation is worried about the impact on jobs for their children. Tsering Sampage, 55, who runs a store at the Kigu Tak market near the Old Bus Stand in Leh, says both his sons are looking for jobs. “Earlier we had reservation in jobs and it was still difficult to get employment. I don’t know if it will be possible now,” he says.

Younger people, seamlessly shifting from Badshah to Billie Eilish at the city’s numerous cafes, are not bursting the bubbly yet either. Namgyal Tundu, 23, a western dance instructor, says that the demand was for a UT with a legislature but the region has lost political representation. “We don’t know what it means for jobs and for our land. Will it be taken over by outsiders,” he asks.

Twenty-two-year old Yangchan Lhamo, who graduated from Delhi, says that overtourism has already had a negative impact on the fragile ecology of the region. “The influx of tourists during the summer months is more than our entire population. They come and trash the place with plastic. Ladakh will not be able to survive an onslaught like this if there are no regulations to curb the numbers,” she says. Tundup Nurbu, a restaurateur, is even more direct, “Let us be clear. UT status was not given to us because we demanded it. Woh Kashmir ko tabah karne ki liye diya hai (It has been given to destroy Kashmir),” he says.

Designer Stanzin Palmo, 26, who has been working to popularise traditional Ladakhi pashmina and textile, is much more optimistic. Palmo, a NIFT graduate who will present her collection at the 2019 Lakme India Fashion Week, says the move could raise awareness about the region. “People don’t know about Ladakh. An independent UT status will help us promote our culture, our handlooms. It is a great opportunity,” she says.

A significant reason that discordant notes are restricted to murmurs is that political leaders have been more than enthusiastic about the decision. Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Council (LAHDC), Leh chairperson Gyal P Wyangal, the Ladakh Buddhist Association and the head of the powerful Hemis monastery HH Gyalwang Drukpa have welcomed the move. This is in part because of the prospect of freedom from Srinagar-focused politicians, whether in Delhi or J&K, and the growing differences between Kashmiri Muslims and Ladakhi Buddhists. Decades ago, the two communities enjoyed close ties whether through inter-marriages or business. Now, relationships are fraught. So Kashmiri Muslims in Leh shop only at Kashmiri shops while Ladakhi Buddhists will patronise their own, say officials. In 2017, a marriage between Ladakhi Buddhist girl and a Kashmiri Muslim brought about protest marches in Leh, while a year later in October 2018, when a Ladakhi girl was harassed on the street by Kashmiris, monks came out to pelt stones and protest.

Small wonder then that Ladakh MP Jamyang Tsering Namgyal’s spirited speech in Parliament finds echo across party lines. Says Congress leader and former LAHDC head Rigzin Spalbar, “The Modi government has fulfilled a long standing demand for the Ladakhis and we have to appreciate that. But we must also ensure that the development of Ladakh does not depend on the whims and fancies of Delhi.”

No one knows this better than Nawang Gyalsen, principal in a government school in Nang village, 27 kms from Leh. Though only an hour’s drive from the city, the school has erratic power, no water connection and a road that reduces to a dirt track closer to the village. He hopes that UT status will mean more infusion of funds into education. “We have no infrastructure. Our children are forced to learn Urdu which is alien to them,” he says.

P Stobdan, academician and former ambassador, says as an adjunct of J&K, Ladakh has no specific personality and has suffered in terms of development. “But UT status is not an absolute protection. It is incumbent on the Centre to take care of Ladakh’s concerns whether it is environment, employment or strategic interests,” he says.

Tourism, trekking

2018: govt opens 5 new routes

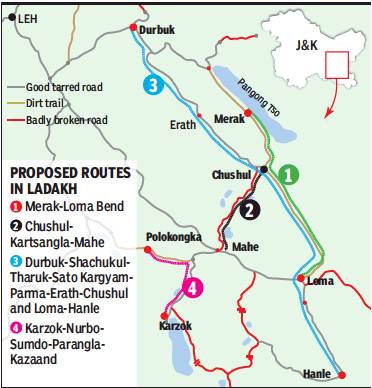

To boost tourism in Ladakh, govt opens 5 new routes, December 19, 2018: The Times of India

From: To boost tourism in Ladakh, govt opens 5 new routes, December 19, 2018: The Times of India

Validity Of Permits Hiked To 15 Days

Visitors now have more options to get high on adventure and adrenaline in Ladakh, the high-altitude cold desert in Jammu & Kashmir. The home ministry on Tuesday cleared the state government’s proposal to open up five new routes through the moonscape for tourists and four trails for trekkers.

That’s not all. The validity of tourist permits for travelling through the new and existing routes has also been increased to 15 days from seven days at present. This will make it easier for tourists to draw up their itinerary across the Ladakh district.

Tourists will now be allowed to travel the Merak-Loma Bend axis, Chushul-Kartsangla-Mahe, Durbuk-Shachukul-Tharuk-Sato Kargyam-Par ma-Erath-Chushul and Loma-Hanley, Karzok-Nurbo-Sumdo-Parangla-Kazaand, and Agham-Shayok-Durbuk.

Trekkers can take their pick from the trails of Phyang-Dokla-Hunderdok, Basgo-Ney-Hunderdok-Hunder, Temisgam-Largyap-Panchathank-Skuru, and Saspol-Saspochy-Rakurala-Skuru.

Most of the new tourist routes are desolate windswept terrain at elevations of 14,000 feet and above, accessible by motorable or fairly navigable dirt roads that run along the Chinese border on some stretches.

But permissions will come with a small restriction on night stays to ensure safety and security of tourists. No trekker will be allowed night stay on any trekking route. However, on some tourist routes, people will be allowed night stays.

The district administration has been pushing for opening up more areas, reflecting the demand from locals . An estimated 3 lakh tourists visited Ladakh this year during the summer tourist season. Tourism boom has brought visible economic prosperity in Leh and Nubra in the north and Man-Merak areas along the Pangong Tso lake.

This follows the success of many tourism initiatives under the PM’s development package-2015 for the state.

Wildlife issues

(Note: This section is limited to issues related to wildlife, and not Ladakh’s wildlife itself, detail about which can be found in the very detailed series Bio-diversity in Jammu, Kashmir, Ladakh: Status Of Biodiversity In J&K . Many more articles on Ladakh’s wildlife can be found through the Search box on the top right above.)

Feral dogs multiply/ 2018

Sanjay Dutta, December 19, 2018: The Times of India

From: Sanjay Dutta, December 19, 2018: The Times of India

Feral dogs have emerged as a menace in Ladakh, preying on exotic wildlife species and attacking people as their packs thrive on leftovers from a rising tide of tourists and tent-dhabas mushrooming across the sparsely populated high-altitude region during the tourist season.

These dogs are threatening the region’s exotic wildlife species, hurting their growth. Most notable among the threatened species is the black-necked crane, J&K’s state bird. They are now taking on much larger animals such as the Tibetan wild ass, known as ‘Kiyang’ in local language. One such incident has been captured by a Mumbai-based wildlife researcher Saurabh Sawant.

Earlier in 2014 and 2015, incidents of these dogs killing a woman in Saspol and a teenage girl in Spituk villages near Leh were reported. Locals say many other incidents of non-fatal attacks go unreported. The problem becomes acute during the harsh winters when food vanishes as most of the tourist trails remain under snow.

“The Changthang plains are the nesting ground for migratory birds. All these are ground-breeders and lay their eggs on the ground. The dogs eat the eggs, which can threaten the future of the species. Himalayan marmots too are falling prey in a big way,” according to Leh wildlife warden Pankaj.

He put the number of feral dogs at 3,500-4,000. “It is considered safe if the number of stray dogs is 3% of human population. It is 30% in Ladakh (Census 2011 population of 1.33 lakh).”

He said these are ferocious, intelligent creatures and hunt in packs. These are seen in Hanle and areas around Tso-Moriri as well as Tso-Kar lakes straddling the Changthang plains, some 250 km from Leh. “Their number is growing in Leh and Nubra as well.”

Since law doesn’t allow culling, sterilisation costly and practically difficult due to the vast expanse, dogs are having a field day in Ladakh.

Much of the blame is put on tourists and the tent-dhabas. “Tourists feed dogs or throw around leftovers. The dhabas dump trash with food. But once these sources of food vanishes in the harsh winters, the dogs become desperate and dangerous,” one field official said requesting anonymity.