Lawyers: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Dress code

2023: HC announces common dress code for interns

February 24, 2023: The Times of India

New Delhi : Delhi High Court said that law interns can enter court complexes in the national capital by wearing a white shirt, black tie and black pants as prescribed by Bar Council of Delhi.

The single bench of Justice Pratibha M Singh also said that the advocates appearing before any courts would have to wear white bands along with the uniform prescribed for the m. “It is clarified that the advocates appearing before any courts, from city civil courts to Supreme Court, would have to wear white bands along with uniform. Interns can enter cour t complexes with black tie, black pants and white shirt as prescribed by Bar Council of Delhi,” directed the bench while disposing of a petition.

The court was hearing theplea , which was m oved by one Hardik Kapoor, a second-year law student, challenging a circular issued by Shahdara Bar Association stating that interns practising at the Karkardooma Court oug ht to wear white shirt and blue coat and trousers. The petitioner claimed that the circular would cause unnecessary financial burden on the interns who work without any stipend o r with a stipend of meagre amount.

The bench further addedthat the Shahdara Bar Association’s circular would be superseded by the uniform prescribed by Bar Council of Delhi, which would be followed uniformly across the city. “The impugned circular would not survive and shall be superseded by the uniform prescribed by Bar Council of Delhi, which would be followed uniformly across Delhi. The petition is accordingly disposed of,” the bench said. Earlier, the court had asked the chairman of Bar Council of Delhi to call for a meeting of all the stakeholders, including the district bar associations and Bar Council of India, to evolve a common consensus regarding a uniform dress code for interns. It had observed that since a larger numbe r of interns enter the premises of district courts and the high court, a uniform policy ought to be arrived at by all the stakeholders.

Foreign nationals practising in India

Korean lawyer and general principles: 2025

Abhinav Garg, March 20, 2025: The Times of India

New Delhi : Delhi High Court has asked the Bar Council of India (BCI) to immediately enrol a South Korean citizen as an advocate so that he can practise in India.

A bench of Justices Prathiba M Singh and Rajneesh K Gupta pointed out that there was no stay on a 2023 single-judge bench’s order allowing him to enrol in India.

"This court is of the opinion that in the absence of any stay which was granted by this court against the Ld. Single Judge’s judgment, withholding the enrolment of the Respondent No.1 would not be permissible," it observed, giving two days’ time to BCI to do the needful.

It noted that after the court’s earlier order, enrolment was issued to Daeyoung Jung, who holds a law degree from the National Academy of Legal Studies and Research (NALSAR) Hyderabad, an institute recognised under the Advocates Act. Jung’s counsel said the Korean national also appeared in the All India Bar Examination (AIBE) where initially his result was reflected as having passed the AIBE examination. However, the portal later showed that his result was withheld. On its part, the BCI said it is still verifying if there is reciprocity given by South Korea to Indian lawyers even as it has challenged the 2023 order. However, the high court said enrolment must be issued immediately while posting BCI’s appeal for hearing on March 28.

BCI moved against a single judge order of 2023 allowing Jung’s plea to enrol himself as an advocate in India. The single judge observed that BCI “clearly appears to have lost sight of the fact that Jung was not a 'foreign lawyer' claiming a right to establish his own legal practice in India. In fact, the petitioner is a foreign national with a degree in law which is recognised under the Act, thus entitling him to seek enrolment.”

The court said that under the Advocates Act, a national of any country may be admitted as an advocate and the right of enrolment of such a foreign national was subject only to the condition that duly qualified Indian citizens were permitted to practise law in the other country.

How a few tar a profession

Delhi: 1988 case dissuades police from action against lawless lawyers

The Times of India, Feb 19 2016

Abhinav Garg

1988 case no excuse for police inaction on lawless lawyers

Observers familiar with Delhi Police's functioning and track record say the force has been wary of handling lawyers' agitations ever since a series of controversial incidents unfolded at Tis Hazari some three decades ago. Trouble began after the police handcuffed a lawyer accused of theft and produced him at a Tis Hazari court. Angry lawyers went on strike and barged into the office of then DCP North -India's first woman IPS officer Kiran Bedi. The police struck back with a massive lathicharge that left several lawyers injured. The police later justified their action saying they took recourse to resolute action to break the advocates' strike and prevent lawlessness in the court complex.

A probe headed by Justice D P Wadhwa differed. Indicting Bedi and other senior police officers of “grave irregularities“, the Wadhwa inquiry faulted the IPS officer for “indiscriminate and un justified“ use of force. Soon, heads rolled, including that of Bedi's who the government shunted out.

Eminent lawyer K K Venugopal represented the Delhi Bar Association in its fight against the police during the legal proceedings that followed. But speaking on the Patiala House outrage, the senior SC lawyer wasn't willing to buy the argument that the 1988 case should hold back the Delhi Police. This, he said, was just an “excuse“ to justify the department's failures.

“They aren't prepared to take action against an MLA indulging in violence. They can allow students and media representatives to be beaten up by lawyers? It is only an excuse that the Tis Hazari incident deterred them. If a police force is posted in a court complex its job is to ensure law and order and rule of law. Who else will you find in court if not lawyers? It is a strange defence,“ the Constitutional expert countered.

His views were shared by others. Senior advocate Dayan Krishnan, who was Special Public Prosecutor for Delhi Police in the Nirbhaya and Nitish Katara cases, too rubbished the excuse. Having briefly been the police's standing counsel in high court, Krishnan is familiar with their functioning. He too refused to accept that police are wary of acting against the errant lawyers.

“Even after the 1988 incident, the police lathicharged lawyers in 2002-03 when a group marched to Parliament. It appears in Patiala House they received instructions not to take any action against those indulging in violence. I don't think Delhi Police is scared to deal with lumpen elements but freedom to act has not been given. Problem is such elements bring a bad name to our entire profession,“ he said.

The conduct of some lawyers

Since economic liberalisation in 1991, the cost of litigation has spiralled. Lawyers’ fees form the major component of it. In an adjournment-friendly judicial system, litigations linger. Lawyers’ fees keep multiplying. The financial drain, loss of time, and emotional and physical exhaustion caused by the labyrinthine queue for justice dissuades many from accessing courts.

In a judgment last week, the Supreme Court hoped that the Centre would heed Law Commission’s recommendations and introduce legislative changes for an effective regulatory mechanism to check violations of professional ethics by lawyers and also ensure access to legal services by regulating the “astronomical” fees charged by them.

In a free economy, it is impractical to fix ‘floor and ceiling’ of fees charged by professionals. A minuscule number of lawyers charge fees running into lakhs for very brief hearings on Mondays and Fridays in the SC. They cater to the super rich clients and corporate houses. Daily earning of this small band of lawyers in the SC on Mondays and Fridays probably exceeds the average annual salary of successful professionals in other fields.

Their strike rate-based reputation, coupled with high fees, probably exerts immense pressure on them to settle for nothing less than a favourable outcome for their clients. Most of them get riled on hearing a no from the judges. When judges are not inclined to grant relief, they use every tactic under their belt, ethical or unethical, to make the judge accede to their demand.

There is another small band of lawyers, who are advocates in court, activists on Twitter and semi-politicians outside the court. Most successful lawyers as well as activist-advocates have a welldefined political lineage or conviction. When they file public interest litigations, the court must entertain these and dare not reject them. The judges who make the ‘cardinal mistake’ of disagreeing with them are quickly branded ‘corrupt’, ‘inefficient’ or ‘government lackey’.

To overcome ‘difficult’ judges, these two categories of lawyers raise their voices

and often make the judge feel deficient in legal knowledge. Some judges stand up to this affront and run the risk of getting branded. And if browbeating a judge does not bring the desired result, they seek the judge’s recusal.

This brand of advocacy by this small group of lawyers is fast gaining ground. High-fee litigation and socio-political standing of lawyers have transformed advocates to employ an adamant ‘I am right’ argument. They have the licence to dissent. But if anyone else dissents with their views, then they set social networks afire by incessantly insinuating about the dissenter’s character and integrity.

In this process, the courts, which were once the granaries of knowledge, have become veritable battle fields. The lines are constantly drawn. The ‘if you don’t agree with me then you are my enemy’ line has gained currency. Respect for each other and judges has diminished. The institution’s reputation has suffered.

We saw this in the Subrata Roy Sahara case. On May 6, 2014, a bench of Justices K S Radhakrishnan and J S Khehar, exasperated by the hounding arguments of renowned lawyers, vented their angst by approvingly referring to Delhi High Court’s response to advocate R K Anand’s plea for recusal of Justice Manmohan Sarin in a case where the counsel was facing criminal proceedings related to the BMW hit and run case.

Justice Sarin had said, “The path of recusal is very often a convenient and soft option. This is especially so since a judge really has no vested interest in doing a particular matter.” Referring to a judge’s oath of office, he had said, “In a case where unfounded and motivated allegations of bias are sought to be made with a view of forum hunting/ bench preference or browbeating the court, then succumbing to such pressure would tantamount to not fulfilling the oath of office.”

Instances of browbeating of judges by advocates are not of recent origin. But it has increased in recent times. In ‘Re: Ajay Kumar Pandey’ [ AIR 1998 SC 3299], the SC had said, “No one can be permitted to intimidate or terrorise judges by making scandalous, unwarranted and baseless imputations against them in the discharge of their judicial functions so as to secure orders which the litigant wants… The liberty of expression cannot be treated as a licence to scandalise the court.”

In M/s Chetak Construction Ltd vs Om Prakash [AIR 1998 SC 1855], the SC had deprecated the practice of making allegations against judges. It had said, “Lawyers and litigants cannot be allowed to terrorise or intimidate judges with a view to secure orders which they want. This is basic and fundamental and no civilised system of administration of justice can permit it.”

In 1937, the American Bar Association adopted the following canon of professional ethics, “The lawyer should not purchase any interest in the subject-matter of the litigation which he is conducting.” This is also part of the ethics code applicable to Indian lawyers.

These days, many lawyers file PILs in which stakes are socially and politically very high, even if one discounts monetary benefits. These lawyers, being author, mentor and force behind these PILs, have an intrinsic interest in sustaining the litigation to keep their position intact in social and political amphitheatres. Some of the high-fees lawyers too suffer this syndrome.

It is time for the legal fraternity — judges and lawyers — to work together to devise means and ways to infuse values and a self-correcting mechanism to protect public faith in the institution. Courts cannot shy away from inquiring into allegations with reasonable proof against judges. But insinuations based on suspicions must not punch holes in the ship delivering justice, for the judicial sea is witnessing rough weather.

Government lawyers

’Performance in courts, not political connection to determine appointment’

An advocate's performance in courts, and not his political connection, would count for herhis appointment as government lawyer, the Supreme Court has said dismissing the Bihar government's plea for a free hand in making appointment of government lawyers.

The Nitish Kumar government engaged attorney general Mukul Rohatgi in addition to standing counsel Shoeb Alam to challenge the Patna High Court's judgement directing the state to follow the model procedure set by the apex court for appointment of government lawyers for district courts and additional advocates general for Punjab and Haryana. The two states were infamous for appointing dozens of advocates as AAGs merely because of their proximity to politicians.

Rohatgi argued before a bench of Chief Justice J S Khehar and Justices D Y Chandrachud and Sanjay Kishan Kaul that the state already has put in place a litigation policy which envisages a process for appointment of government lawyers. “Where will this end? If the HC can direct today how government lawyers should be appointed, tomorrow it would be for public sector enterprises, panchayats and other semigovernment organisations,“ he said.

With the common knowledge that governments are the biggest litigants, the CJIheaded bench said: “The cases involving the governments were crucial in many aspects touching key areas of governance. A certain degree of competence was required from the advocates to represent the government and render meaningful assistance to the courts. Have some mercy on the courts too. Mere connec tion with politicians should never be the criteria to appoint an advocate as government lawyer.“

With these remarks, the SC dismissed the Bihar government's appeal against the November 17, 2016 judgement of the Patna HC, which had asked the state government to adopt the Punjab and Haryana model dictated by the apex court for selection of government lawyers in Brijeshwar Prasad case last year.

The SC had also said that though these directions were for Punjab and Haryana, other states would do well to reform their system of selection and appointment of government lawyers to make the same more transparent, fair and objective. The HC had faulted the Bihar litigation policy saying it did not satisfy the criteria of transparent, fair and objective appointment process.

In Brijeshwar Prasad case, the SC had regretted that “the states continue to harp on the theory that in the matter of engagement of state counsel, they are not accountable and that engagement is only professional andor contractual, hence, unquestionable. It is too late in the bay for any public functionary or government to advance such a contention leave alone expect this court to accept the same“.

International forums

Rajput elected to ILC by UNGA

In major diplomatic victory, Indian lawyer elected to ILC, Nov 05 2016 : The Times of India

UNGA Returns Rajput By Record Vote

In what the government described as a major diplomatic victory for India, 33-year-old Supreme Court lawyer and PhD student Aniruddha Rajput was elected to International Law Commission (ILC) by the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) with a record number of votes. Established by UNGA, the Geneva-based ILC encourages promotion of international law and its codification. Rajput got 160 votes, topping the Asia-Pacific group in the election which was held through secret ballot.

“This is a real honour for me and I want to thank the ministry of external affairs (MEA), especially India's permanent representative to UN Syed Akbaruddin, for their support,“ Rajput told TOI.

Japan's Shinya Murase got the second highest number of votes in the Asia-Pacific group at 148, followed by Mahmoud Daifallah Hmoud of Jordan and Huikang Huang of China with 146 votes each, Korea's Ki Gab Park with 136 votes, Ali bin Fetais Al-Marri of Qatar with 128 votes and Hong Thao Nguyen of Vietnam with 120 votes.

This was the first time that the MEA did not nominate anybody from its pool of lawyers for the membership and instead decided to go with an outsider.

An alumnus of the London School of Economics and Political Science, Rajput was a member of an expert group appointed by the Law Commission of India to study and comment upon the Model Bilateral Investment Treaty 2015 of India, according to his profile submitted to the UN. He has written several books, chapters, articles, conference papers on diverse legal subjects.

The newly elected members will serve five-year terms of office with the Geneva-based body beginning January 2017. The members have been elected from five geographical groupings of African, Asia-Pacific, Eastern European, Latin American and Caribbean and Western European states.

While some have said that Rajput's links with R S S might have had a role in his nomination, which is denied by MEA, he himself said, “International relations is important but member-states of the UN have to vote for the candidate who has recognised competence in international law and the number speaks for itself.“

Judges/ courts: Lawyers vis-à-vis judges/ courts=

Insinuations through the media

Dhananjay Mahapatra, Jan 31, 2019: The Times of India

Insinuations by lawyers make our job hard, says Supreme Court NEW DELHI: Ringing the alarm bell, the Supreme Court said in a hard-hitting judgment that it was becoming increasingly difficult for judges to render justice in a fair, impartial and fearless manner because of insinuations made by advocates in cases of political importance. “Whenever any political matter comes to court and is decided, either way, political insinuations are attributed by unscrupulous persons/advocates. Such acts are nothing but an act of denigrating the judiciary itself and destroys the faith of the common man which he reposes in the judicial system,” a bench of Justices Arun Mishra and Vineet Saran said in its 75-page judgment. Taking note of the tendency among some advocates to rush to the media from courtrooms, the bench said “hunger for cheap publicity is increasing” and termed it as anathema to the standards of the noble profession. “Statutory rules prohibit advocates from advertising and cater to press/media,” it said, adding it had become common to dish out “distorted versions of court proceedings”. Cases cannot decided by media trial, says apex court This had a chilling effect on judges who could not go to the media with their point of view, the bench said. “It is making it more difficult to render justice in a fair, impartial and fearless manner,” the bench said and complained that making public accusations against judges was a tactic adopted by unscrupulous elements to “influence the judgment and even to deny justice with ulterior motives”. In the last year, apex court judges have faced a lot of insinuations from activist lawyers while dealing with politically sensitive matters — plea of Muslim parties for reference of Ayodhya land dispute to a five-judge bench, petition seeking quashing of UAPA charges against social activists including Sudha Bharadwaj and Gautam Navlakha, plea for SIT probe into judicial officer B H Loya’s alleged suspicious death, PILs for probe into Rafale jet purchase and petitions challenging the Centre’s decision to divest then CBI director Alok Verma of his powers. “Something has to be done by all concerned to revamp the image of the bar,” the SC said. Writing the judgment for the bench, Justice Mishra said, “It is impermissible to malign the system itself by attributing political motives and false allegations against the judicial system and its functionaries. Judges who are attacked are not supposed to go to the press or media to ventilate their point of view.” Taking note of hype created in media by certain advocates in matters of political importance, the SC said, “Cases cannot be decided by media trial... No outside interference is permissible. A lot of sacrifices are made to serve the judiciary for which one cannot regret as it is with a purpose and to serve judiciary is not less than the call of military service. “For the protection of democratic values and to ensure that rule of law prevails in the country, no one can be permitted to destroy the independence of the system from within or outside... Let each of us ensure our own institution is not jeopardised by the blame game and make an endeavour to improve upon its own functioning and independence.” The SC was testing the validity of the rule framed by Madras high court empowering it to debar an advocate to control situations which arose in the past, including shouting of slogans, using foul language against judges and vandalism. Though anguished by past conduct of lawyers in the HC, it struck down the rule and said the HC could not usurp disciplinary powers vested in bar councils.

Lawyers’ fees/ earnings

As in 2019

Dhananjay Mahapatra, July 8, 2019: The Times of India

Lawyers will constitute the largest group of individual professionals who will be affected by a steep hike in tax rate on crorepatis, which was proposed in the budget by India’s first fulltime woman finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman. The proposed tax rate of 39% on an annual income of Rs 2-5 crore and 42.7% on annual income of over Rs 5 crore would be applicable to many well-known figures in the legal world. It would also include many retired judges who are sought after as arbitrators and are raking in the moolah.

Some successful lawyers earn over Rs 1 crore on a daily basis. Remember the bill raised by India’s ace criminal lawyer Ram Jethmalani on Delhi chief minister Arvind Kejriwal for defending him in a Rs 10 crore defamation suit filed by successful lawyerpolitician Arun Jaitley?

Jethmalani charged a retainer fee of Rs 1 crore and Rs 22 lakh per appearance before the trial court. He will not feel the heat of the stiff tax proposed by Sitharaman. He has earned his fame and money and has quietly retired from practising law on a day to day basis. Others who could measure up to him in success, knowledge and wealth, achieved through practice of law, would include Soli J Sorabjee, Fali S Nariman and K Parasaran. Unlike Jethmalani, they still take up a select few cases and appear before the Supreme Court. A few years ago, all three would have been bracketed among the super rich based on their annual income, but not now. A few others who will also escape Sitharaman’s ‘tax the super rich’ proposal will be Rohinton F Nariman, U U Lalit and L Nageswara Rao as they accepted offers and become SC judges, sacrificing huge personal incomes.

But those who will feel the pinch of higher tax include Harish Salve, Mukul Rohatgi, Kapil Sibal, A M Singhvi, Gopal Subramanium, P Chidambaram, Salman Khurshid, Parag Tripathi, K T S Tulsi, Maninder Singh, Vikas Singh, Ranjit Kumar, Siddharth Luthra, Ajit Sinha, Shyam Divan and K V Vishwanath. The list is much longer but it is difficult to recall names of all who earn much more than Rs 2 crore a year with their law practices in the SC and high courts. The taxmen will not find it as difficult!

The profession of law became a cash-rich occupation post-liberalisation in 1992. In the next two decades, fees of successful lawyers zoomed and reached a level where they were unaffordable for most unless they decided to take up a case pro bono. There will not be many in any other profession across countries who command fees of Rs 15-20 lakh for a five-minute argument in a case before the SC. There are instances where senior advocates demand consultation fees running into lakhs for discussing a case with the briefing counsel while travelling in a car from the SC to the Delhi high court, a distance covered in 10 minutes in peak traffic. But how did the legal profession take birth in India? The British East India Company’s Charter of 1774 empowered courts existing then to approve, admit and enrol advocates and attorneys to plead and act on behalf of suitors, simultaneously conferring power on courts to remove lawyers from the rolls on a reasonable cause and to prohibit practitioners not properly admitted and enrolled from practising (Law Commission’s 131st report, 1988).

After the British took over administration of India in 1858, Indian High Courts Act, 1861, was enacted and HCs were established in Calcutta, Madras and Bombay in 1862. This was followed by HCs in Allahabad (1880), Patna (1916) and Lahore (1919). The Law Commission report said, “Although establishment of the Indian legal profession was originally a case of ‘transfer of a western institution’ brought about by a foreign power to meet exigencies of administration in India, it soon assumed leadership of national struggle for independence. It acquired its awareness because of its connection with British democratic institutions through legal literature.”

India’s struggle for independence was led by a lawyer, Mahatma Gandhi. There were many stalwart lawyers — Motilal Nehru, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, Bal Gangadhar Tilak, C Rajagopalachari, Lala Lajpat Rai, C R Dar, Saifuddin Kichlew, Rajendra Prasad, Bhulabhai Desai, Jawaharlal Nehru, Madan Mohan Malviya, Tej Bahadur Sapru, Asaf Ali, B R Ambedkar and K N Katju — who played stellar roles in the freedom struggle. They richly contributed for ‘swaraj’ without amassing personal wealth. Not many of them, except Motilal and Jawaharlal, could be categorised as rich, money-wise. The Law Commission had said, “Till the advent of freedom, it cannot be gainsaid that the members of legal profession occupied a vantage position.” And then, it asked, “Is that the position maintained till today? In the post-independent era, has the legal profession maintained and augmented its position as leaders of thought and society?”

It went on to say, “No one can seriously question, though evidence of a concrete nature is hard to come by for reasons not difficult to foresee, that the fees charged (by advocates) have reached astronomical figures. There may be a class of litigants who can afford the same. But that microscopic minority class need not destroy the culture of legal profession nor the market of fees.” If 30 years ago, the commission headed by retired SC judge D A Desai thought fees quoted by lawyers were astronomical, it is hard to find a term which can appropriately describe the fees sought by them today.

By imposing a higher tax on the super rich, many of whom are lawyers, the government may add a few more crores to its kitty but unless these successful legal practitioners attempt to achieve a healthy balance in taking up cases of rich and poor litigants, their stature as money minting machines will not get a humane face.

Pioneering the high fee demand

Dhananjay Mahapatra , May 22, 2021: The Times of India

Who started the trend of senior advocates demanding very high fees for appearing for litigants in Supreme Court?

Senior advocates A M Singhvi and Vikas Singh, during banter in video-conferencing platform for a vacation bench in Supreme Court, revealed that it was former law minister Shanti Bhushan who started the trend of charging high fees for single appearance in cases before the apex court.

Singhvi, one of the top lawyers of the country commanding fees that could be matched by few at present, said finding such high charges awkward, senior advocate Murli Bhandare, who held two terms as president of Supreme Court Bar Association, had proposed a resolution capping the legal fees to be charged by senior advocates.

“But, Shanti Bhushan tore that resolution and threw it in the dustbin and asked as to how SCBA could implement its resolution limiting the fees of senior advocates,” Singhvi said. Singh agreed with Singhvi that Bhushan was the pioneer in charging high fees. At present many senior advocates command a fee in excess of Rs 10 lakhs for arguing miscellaneous matters before the Supreme Court, which generally does not last more than 10 minutes.

The banter started with SCBA president Vikas Singh jokingly inquiring from solicitor general Tushar Mehta as to who is earning more, he or attorney general K K Venugopal. When SG said that he could not disclose the earnings of the AG, Singh said that “the cat is out of the bag”. SG immediately said that Venugopal had been a high fee charging lawyer even before he became an AG. “AG's income is definitely much more than mine,” he said.

In his characteristic deftness in changing the course of the debate, SG in lighter vein said Vikas Singh as SCBA president should pass a resolution similar to the one attempted by Bhandare. “You pass the resolution and together we will take it to Singhvi,” he said. A smiling Singhvi was saved from reacting as the bench of Justices Vineet Saran and B R Gavai assembled.

With the senior advocates and the SG unsure whether the judges heard the banter, it was Singhvi who lightened the moment further by saying that in the absence of physical hearing, the advocates are using the video-conference facility to engage in some light-hearted naughty conversations.

The bench disarmed them by saying “we have been at the bar before becoming judges. We know how lawyers exchange naughty gossips”.

Lawyers who defended much-hated clients

The Times of India, Apr 10, 2016

Amulya Gopalakrishnan, Swati Deshpande & A Subramani

Why they defend the indefensible

No matter how horrific a crime, the accused deserves a defence counsel. But it is not a job for the faint-hearted, say lawyers who've represented some of the most hated figures in recent times

"Everyone will hate me, but at least I'll lose," says American lawyer James Donovan, played by Tom Hanks in Bridge of Spies, when asked to defend a Soviet spy. Having taken on this thankless, risky job, he does what any lawyer should do sincerely try to secure justice for his client.

People often wonder what prompts lawyers to defend a seemingly "monstrous" or "indefensible" individual. Those questions are being asked again, as the Supreme Court appointed senior advocates Raju Ramachandran and Sanjay Hegde as amicus curiae in the Nirbhaya gangrape case that galvanized the nation. Though they already have lawyers, Ramachandran and Hegde have been asked to make sure that the four convicts on death row are given a "full and fair" hearing.

Ramachandran, who has been amicus curiae for 26/11-accused Ajmal Kasab and has also represented Yakub Memon in the Supreme Court, is used to having his motives questioned. "When an accused is undefended, the court appoints a lawyer to defend him. To refuse to assist the court, when asked, is a dereliction of duty," he explains.

When media and popular opinion demonize the accused, as they did with the Nirbhaya convicts or Kasab, it is a lawyer's job to make sure they get the full hearing they are owed. This is not an endorsement of rape or terrorism. As all first-year law students learn, the lawyer is not defending the crime, but due process.

In our adversarial justice system, if you're hauled into court, you need counsel for a fair trial. "The accused has the right to assert his or her innocence by picking holes in the prosecution case. And it is the duty of the prosecution to prove the case beyond reasonable doubt. Everything that can be said in favour of the accused needs to be said," says Ramachandran.

Take the Kasab case. To a nation shocked by the CCTV footage of his rampage at Chhattrapati Shiva ji Terminus, his guilt was clear as daylight. And yet, it had to be established by the court. It was hard to find a defence lawyer, and the few who came forward were threatened by political activists. In fact, the Bombay Metropolitan Magistrate Court's Bar Association unanimously resolved not to represent alleged terrorists. This is not an isolated incident. Bar associations often turn on lawyers who defend difficult clients.

Anjali Waghmare, the first advocate appointed for Kasab, was dismissed immediately because of a clash of interests. Abbas Kazmi, who defended Kasab until November 2009 — he was replaced by his assistant KP Pawar — had mounted a spirited defence. Pawar, too, had argued for leniency, saying that "the court should explore the possibility of Kasab's reform and rehabilitation. We have to consider that he is a young man who was brainwashed and blinded by an extremist organization". Kasab's death sentence, though, was upheld all the way until the President's final nod.

"Defending the indefensible is not for the weak. It is not only the lawyer but his or her family that needs to be strong, says Kazmi. His family went through their own trial in those months, and required separate police protection. "I had three or four police guards at all times," he says. Friends and well-wishers used to express concern and anguish. "They'd ask: why are you risking your life?" recalls Kazmi.

The same dilemma faced S Duraiswamy, who defended the accused in the Rajiv Gandhi assassination case in June 1991, braving intimidation from Congress workers. "No other leading criminal lawyer would take up the case," he says. "The court was initially hostile, but as the trial progressed I was able to advance arguments with ease. In 1991 itself, I argued that the suspects could not be tried under TADA. Though the trial court rejected this line, in 1999 the Supreme Court came around and declared that TADA could not be invoked because it was not an act of terrorism." Some lawyers may have a personal code on the subject. "As a general rule I don't appear in rape cases as defence counsel," says senior lawyer Mahesh Jethmalani. But this is a deviation from the professional norm, which requires lawyers to take on anyone who needs counsel.

"A lawyer is not meant to act as a judge before the trial is through," explains Ramachandran. Except for pressing personal reasons or conflicts of interest that make it difficult to push the client's case, an advocate has to follow what Ramachandran terms the "British cab rank rule". "A cab driver at Paddington station is bound to take any person who comes and offers the full fare, and so it is with lawyers," he says.

There are several advocates of comparable standing who are asked to step in on controversial cases, not necessarily criminal ones. "Senior advocates have the duty to reinforce this from time to time by accepting such cases", says Ramachandran. It is, in fact, in the most emotionally charged cases, like that of Nirbhaya, that the rule of law must gird itself most strongly.

Legal aid, free

Majority have little faith in the counsel provided

Most Go For Them Out Of Compulsion: UGC-Funded Study

A pioneering study on Delhi's legal aid system reveals that lack of commitment and competence of lawyers has badly hit a programme that receives crores of rupees from the government.

The empirical study, funded by University Grants Commission (UGC), shows that a majority of those who avail legal aid opt for it out of compulsion and have little faith in the counsel provided under the scheme.

Statutory bodies such as National Legal Services Authority (NALSA) and Delhi State Legal Services Authority (DSLSA) have been set up to ensure access to poor litigants who can't afford a private lawyer.

The study, authored by National Law University Delhi (NLUD) professor Jeet Singh Mann, focused on “Impact Analysis of legal Aid Services provided by the Legal Aid Counsels on the Legal Aid System in City of Delhi“.

Mann analysed 11 district courts in Delhi and the high court. His research reveals that almost 50% of those interviewed under the category of beneficiaries of legal aid avail of the service only when they do not have any resource to engage private legal practitioners. Though the Constitution and Legal Services Authorities Act 1987 envisage that poor get access to justice, the study laments that “ground realities depict a shoddy picture of the legal aid programme“.

Due to a variety of factors -chief being disinterested and ill equipped legal aid la wyers -“legal aid system is not functioning effectively and also not catering to the requirements of the beneficiaries“, the report adds.

It also cites the experience of over 170 judges whose courts regularly see poor and indigent persons appearing who can't afford a lawyer. “As per the considerate views of 89.30% of senior judicial officers such as additional session judges, they do not prefer the involvement of legal aid counsel (LAC) in serious crimes such as rape, murder, culpable homicide not amounting to murder and narcotics. They always consider the appointment of amicus curiae, generally experienced legal practitioners of competency known to the judicial officers, to protect the interests of poor people, who are not in a position to engage a legal practitioners on their own,“ the study points out.

The report also says it is visible from the data that legal aid counsel “are not considered trust-worthy and competent to protect the interest of poor people in serious crimes“ and recommends more effective monitoring and greater control on empanelled lawyers as also on timely payments to keep them engaged in the system.

To begin with, the study stresses the need to have a more rigorous empanelment process as most of the LAC view Legal Aid services as just a platform to achieve other better employment opportunities. This, in turn, translates into “lack in the zeal and commitment towards their work“ affecting the quality of legal aid services across Delhi, the report concludes.

Legislators who are lawyers

SC, 2018: MPs/ MLAs are not employees, can practise law

Dhananjay Mahapatra, MPs not employees, can practise law: SC, September 26, 2018: The Times of India

Ruling A Relief For Lawyers-Turned-Legislators

In a big relief to several senior advocatesturned-legislators, the Supreme Court rejected a PIL which sought a ban on MPs, MLAs and MLCs from practising as lawyers in courts because they drew salaries and perks as people’s representatives.

A bench of Chief Justice Dipak Misra and Justices A M Khanwilkar and D Y Chandrachud dismissed the PIL by advocate Ashwini Upadhayay and said legislators might be getting salaries and perks from the Consolidated Fund of India but could not be termed employees of anyone to attract disqualification to practise as advocates.

“The fact that legislators draw salary and allowances from the Consolidated Fund in terms of Article 106 of the Constitution and the law made by Parliament in that regard, it does not follow that a relationship of a full-time salaried employee(s) of the government or otherwise is created,” said Justice Khanwilkar while dismissing the PIL.

Had the court agreed for a ban as sought by the PIL, it would have affected successful advocate-turned-politicians Kapil Sibal, P Chidambaram, A M Singhvi, Vivek Tankha, K T S Tulsi, Arun Jaitley and Ravi Shankar Prasad (the last two used to practise when they were opposition MPs but stopped after becoming ministers).

Justice Khanwilkar said MPs, MLAs and MLCs occupied a unique position as they took oath but did not get appointed to a post to be termed an employee unlike the PM, CMs and ministers. “The fact that disciplinary or privilege action can be initiated against them by the Speaker of the House does not mean they can be treated as full-time salaried employees. Similarly, participation of legislators in the House, by no standards can be considered as service rendered to an employer,” he said.

The SC said it was for the Bar Council of India to consider whether practise by legislators could impinge upon their duties towards the House concerned.

“To sum up, we hold that the provisions of the Act of 1961 and the rules framed thereunder do not place any restrictions on the legislators to practise as advocates,”the bench added.

The SC said it was for the Bar Council to consider whether practice by legislators could impinge upon their duties towards the House concerned

Professional duties, discharge of

Notices/ summons to lawyers for appearing for accused/ giving legal advice

Dhananjay Mahapatra, June 26, 2025: The Times of India

New Delhi : Close on the heels of ED’s controversial summons to senior advocates Arvind Datar and Pratap Venugopal, SC said probe agencies or police could not issue notices or summons to lawyers, merely because they appeared for an accused or gave legal advice.

Staying Gujarat police SC/ST cell’s notice to the advocate of an accused to appear as a witness, a bench of Justices K V Viswanathan and N Kotiswar Singh took cognizance of the larger issue and sought assistance from attorney general R Venkataramani, solicitor general Tushar Mehta, Bar Council of India chairperson Manan Mishra, SCBA president Vikas Singh and SC Advocates-on-Record president Vipin Nair. “What is at stake is the efficacy of administration of justice and capacity of lawyers to conscientiously, and more importantly, fearlessly discharge their professional duties,” it said. “Since it is a matter directly impinging on the administration of justice, to subject a professional to the beck and call of an investigation agency/prosecuting agency/police when he is a counsel in the matter, prima facie it appears to be untenable, subject to further consideration by the SC.

In view of the importance of the matter, let the papers be placed before the CJI for passing such directions he deems appropriate,” it added.

Professional ethics

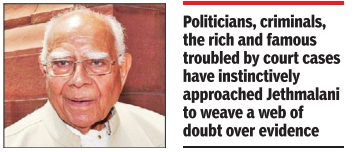

Ram Jethmalani: derogatory word blamed on client's instructions

How does one introduce Ram Boolchand Jeth malani? A lawyer par excellence? Irrepressible? The proverbial phoenix in the inseparable legal-political theatre of India, he has constantly reinvented and reinvigorated himself from decade to decade. In the process, he has earned fame in and outside courts. But his caustic tongue continues to be a magnet for controversies.

Jethmalani, who will celebrate his 94th birthday on September 23, has been a teacher of law to judges, advocates and politicians since he took part in the murder trial against K M Nanavati in 1959.

Politicians, criminals, businessmen, rich and famous troubled by court cases have instinctively come to him, trusting his magically analytical brain to weave a web of doubt over evidence to persuade judges to give the benefit of doubt to the accused.

If there was a celestial court to decide the consequences of divine wrath, he would have been the ideal advocate to plead for leniency .Jethmalani is that kind of lawyer, who is best described by American comedian Steven Wright, “I busted a mirror and got seven years bad luck, but my lawyer thinks he can get me five.“

A non-exhaustive list of his clients gives a glimpse of the immense trust litigants repose in his ability L K Advani, Amit Shah, Lalu Prasad, J Jayalalithaa, B S Yeddyurappa and Kanimozhi; Haji Mastan and Harshad Mehta; Asaram Bapu and Baba Ramdev; Parliament attack case accused. The list would remain incomplete if one forgets to mention his demolition of the Bofors payoff case to get the Hinduja brothers discharged.

His legal prowess earned him friends in politics. He had become active in politics during Emergency and got elected to Lok Sabha for the first time in 1977 from Bombay .Since 1988, he has been a member of the Rajya Sabha, representing Rajasthan, Bihar and Karnataka in the upper House. Jethmalani has also got himself embroiled in legal suits. In 1983, he sued Swaraj Paul in London following a spat with him. His verbal duel with Subramanian Swamy , during proceedings of M C Jain Commission inquiring into the events leading to assassination of Rajiv Gandhi, led to a defamation litigation between them.

So, it was no surprise when Delhi CM Arvind Kejriwal rushed to him when facing civil suit and criminal case filed against him by finance minister Arun Jaitley . Besides Jethmalani's proven prowess as a lawyer, Kejriwal also chose him considering the former's hostility for Jaitley. It worked well for both Kejriwal and Jethmalani for some time. Jethmalani used the opportunity to keep embarrassing Jaitley during cross-examination.

The tables turned on May 17, when Jethmalani got carried away and used a derogatory word for Jaitley , who kept his cool and asked Jethmalani whether the word was used by himself or on his client's instructions. “Client's instruction“ was Jethmalani's instinctive reply. Jaitley promptly slapped another defamation suit against the CM.

Rattled, Kejriwal denied instructing Jethmalani to use the word. Jethmalani never takes kindly to anyone who discredits him, rightly or wrongly . If he can bite with words, he stings with his tail too. The fallout was swift and furious. Jethmalani exited as the CM's counsel, but not before sending a stinging letter to his erstwhile client. But in the process, he probably crossed the line of professional ethics for advocates drawn by the Bar Council of India. He made public the letter giving details of what could be privileged communication between him and his client.

For, the rules on an advocate's duty towards the court say,“ An advocate shall be dignified in use of his language in correspondence and during arguments in court. He shall not scandalously damage the reputation of the parties on false grounds during pleadings. He shall not use unparliamentary language during arguments in the court.“ Jethmalani also appeared to breach the rule on an advocate's duty towards his client, which says, “ An advocate should not ordinarily withdraw from serving a client once he has agreed to serve them. He can withdraw only if he has a sufficient cause and by giving reasonable and sufficient notice to the client. Upon withdrawal, he shall refund such part of the fee that has not accrued to the client.

“It shall be the duty of an advocate fearlessly to uphold the interests of his client by all fair and honourable means. An advocate shall do so without regard to any unpleasant consequences to himself or any other. He shall defend a person accused of a crime regardless of his personal opinion as to the guilt of the accused. An advocate should always remember that his loyalty is to the law, which requires that no man should be punished without adequate evidence.“

Moreover, Section 126 of Indian Evidence Act, 1872 provides, “No barrister, attorney , pleader or vakil shall at any time be permitted, unless with his client's express consent, to disclose any communication made to him in the course and for the purpose of his employment as such barrister, pleader, attorney or vakil, by or on behalf of his client, or to state the contents or condition of any document with which he has become acquainted in the course and for the purpose of his professional employment, or to disclose any advice given by him to his client in the course and for the purpose of such employment.“

No one can ever imagine teaching law or rules to Jethmalani. But sometimes, even the best slip.

`Senior advocate' designation

SC wants transparent procedure

Law degrees from reputed foreign universities and years of practice in courts are no guarantee for a lawyer to earn the `senior advocate' designation from the Supreme Court.

This was stated by a bench of Chief Justice T S Thakur and Justice D Y Chandrachud and Justice L N Rao on Friday in response to allegations that the `senior advocate' designation was being increasingly given arbitrarily to undeserving lawyers through a non-transparent procedure without making public the criteria of evaluation.

The transparency flag was raised by senior advocate Indira Jaising, the first woman to be appointed as a law officer for the Union government during UPA regime. She said it is a perception that senior advocate designations were gained through lobbying and kinship and it has become an elite club restricted to a few.

“Those who have domain expertise in environment, public interest litigations and those who have spent large number of years practising in the Supreme Court do not get considered for the designation,“ she complained and suggested that there should be a codified evaluation process followed by an interview before grant of the designation.

She was supported by senior advocate A M Singhvi who said there should be five or six listed discrete qualiti es for which an advocate should be assessed. There is also a vociferous section of advocates, led by advocate Mathew Nedumpara, opposing the present system of designating senior advocates.

But the bench said it evaluated advocates on a daily basis when they appeared before the judges in the Supreme Court, and took note of their knowledge in law, court craft and standing at the bar -the three cardinal qualities that play a huge role in designating a lawyer as senior advocate.

“Neither degrees from fo reign universities, nor number of years of practice could automatically make a lawyer earn the senior designation,“ the bench said. But with many high courts continuing to confer senior advocate designation on lawyers who did not even practise before that HC, the words of the CJI-headed bench failed to convince the petitioner.

Attorney general Mukul Rohatgi and Supreme Court Bar Association president Dushyant Dave agreed with the court that it was at the discretion of the SC judges to decide who should be designated as senior advocate. However, they said it would be proper to seek views of eminent members of the bar on advocates applying for senior advocate designation.

The bench said it would pass orders on the petition and indicated that it was not averse to making a few changes in the procedure for designating lawyers as senior advocates.

SC’s guidelines, 2017

Acquiring that much sought after status, elevating and money spinning `senior advocate' designation for a practising lawyer just became even tougher than being selected for appointment as a constitutional court judge.

The Supreme Court laid down elaborate and stringent guidelines, applicable to both the apex court and high courts, to evaluate merit and suitability of lawyers, who have put in a minimum 10 years in the profession and have applied for senior advocate designation. Conferment of the designation elevates a lawyer to a select band of senior advocates who command much higher fee from clients compared to advocates.

Senior advocate Indira Jaising, who has discarded the senior advocate's gown but not the designation, had first raised the banner of revolt against the “arbitrary and opaque“ manner in which the SC selected a group of advocates for the coveted designation two years ago. A few names in that list had raised eyebrows, leading to Jaising filing a petition.

She was soon joined by many advocates and lawyer bodies who alleged that the selection of `senior advocates' was heavily tilted towards the kith and kin of those already in the big league and ignored those who had laboured honestly and diligently for years without a lineage to flaunt.

A bench of Justices Ranjan Gogoi, R F Nariman and Navin Sinha appreciated the heartburn caused by perceptible discrimination in conferring senior designation status to lawyers, some of whom were unanimously singled out by lawyers as undeserving. The bench laid down an eight-point check list, which is far more stringent than the method employed to select judges for the SC and HCs.

2023/ SC upholds system

SC’s Verdict is in line with constitutional principles

Oct 18, 2023: The Times of India

By Hitesh S JainIn April 2023, the Supreme Court transferred to itself a batch of petitions filed seeking legalisation of same sex marriages in India. The petitioners essentially sought the interpretation of the term 'marriage' in the Special Marriage Act, 1954 (SMA) to include a marriage between 'persons' as opposed to just between male and female and for Section 4 of the SMA to be declared unconstitutional. They thus challenged personal laws related to marriage and the SMA on the grounds that these laws did not recognise same-sex marriages. In response, the Centre, relying on the doctrine of separation of powers enshrined under the Constitution, submitted that the debate, if any, on equal marriage and/or same sex marriage ought to be put up before Parliament. The SC was thus faced with the conundrum of not only balancing societal and individual rights but also deciding the contours of its own powers without impinging on the legislature's powers.On October 17, a five-judge bench pronounced its judgment in the case of Supriyo@Supriya Chakraborthy v. Union of India & Anr. The SC has unequivocally recognised the right of union and partnership of queer couples. It has asked the centre to proceed with formation of a committee to decide rights and entitlements of persons in queer unions. This committee will consider the following aspects: Inclusion of names in family ration cards, enabling queer couples to nominate their partners for joint accounts, rights accruing to partners for statutory dues such as pension and gratuity. The SC has also clarified that marriage is not a fundamental right, however, the rights of the LGBTQ+ community have to be recognised and protected with the force of law. Through this judgment, the SC has observed that separation of powers as a doctrine is elastic. However, the intention and manner in which the judgment has yielded to Parliament's decision-making power is testament to the SC's conscious adherence to institutional comity.It has always been the Centre's stand that questions and matters relating to same sex marriage are not a matter of being 'for' or 'against' the LQBTQ+ community. The government's efforts to uphold the rights of the LGBTQ+ community are well documented. In fact, the hearing of these batch of petitions came at the time when the SC had already passed landmark judgments in the case of Navtej Singh and NALSA v Union of India. Notably, none of these judgments have been attempted to be scuttled by the Centre, which has honoured the SC's verdicts and worked towards a progressive and inclusive society to give effect to the rights interpreted by the court.Questions of marriage, succession and maintenance in India are all governed by personal laws. This is precisely why the SC restricted itself to the challenge under SMA. However, questions of marriage naturally have an effect on other familial rights and the domino effect is vast. The government's stance was socio-legal, as to whether the judiciary's authority to indulge in this sphere amounts to overreach and whether such interpretations can be viewed in isolation. As submitted before the SC, any interpretation as sought by the petitioners would likely affect over 160 laws. Unlike matters where fundamental rights are enforced, their scope widened and/or defined in Part III of the Constitution, the question of equal marriage is not a mere matter of judicial interpretation.Questions of marriage and family permeate through the very fabric of Indian society. Any reference to American and/or European jurisprudence in this regard is akin to comparing apples with oranges. In a diverse social set-up with specific emphasis on personal laws, to read into provisions of the SMA to account for equal marriage cannot be at the cost of distinctions specifically mandated under personal laws. Any attempt by the SC to grant such reliefs would have stirred a hornet's nest.The judiciary has now indicated its alignment with the doctrine of separation of powers, while also recognising the need for practical benefits that ought to accrue to the queer community on account of their union/partnership. The SC was faced with the conundrum of distinguishing between a question of judicial interpretation vis-a-vis recognition of substantive rights, albeit in isolation. Which organ of the State is empowered to grant rights that affect the fabric of a democratic society? Is it the people's representatives, the legislature, or the indirectly appointed judiciary which is unaccountable to the electorate? With this verdict, the SC has answered the question in alignment with constitutional principles and basic tenets of constitutional democracies. It has balanced its own powers and upheld the rights of a marginalised sector of society.The SC observed that striking down provisions of SMA would relegate the nation back to the pre-independence era, while reading words into the SMA would tantamount to assuming the role of the legislature, which would be ex-facie unconstitutional. In realising that the legitimacy of marriages brings with it more important practical benefits/rights, the SC has deferred the decision to Parliament but has in the same breath ensured that all rights that accrue by way of marriage are granted by the State to members of the LGBTQ+ community. Ultimately, the SC has ensured that while personal laws and sentiments towards those laws are respected, no citizen of India is to suffer on the basis of their sexual orientation.(The writer is Managing Partner, Parinam Law Associates)

`Senior advocate' in position

2024: women lawyers

January 20, 2024: The Times of India

New Delhi : Supreme Court designated a record 11 women as senior advocates while granting the tag to a total of 56 lawyers, reports Dhananjay Mahapatra. Only 13 women lawyers have got the coveted gown from the highest court since it designated Indu Malhotra senior advocate in 2007.

If one counts five retired women high court judges — Shobha Dixit (1998), K K Usha (2004), Sharda Aggarwal (2006), Rekha Sharma (2015) and Mridula Mishra (2018) — designated senior by the SC, women advocates given the designation add up to 18, among the 436 to be designated such since 1966, before Friday’s list.

On Friday, the full court of the SC led by CJI D Y Chandrachud, a supporter of women’s increased participation in all spheres of life, decided to designate 56 lawyers as senior advocates. Among them were 11 women — Shobha Gupta, Swarupama Chaturvedi, Liz Mathews, Karuna Nundy, Nisha Bagchi, Uttara Babbar, Haripriya Padmanabhan, Archana Pathak Dave, N S Nappinai, S Janani and Shirin Khajuria.

Apart from Malhotra, the 12 other women lawyers designated senior advocates by the SC are Meenakshi Arora, Kiran Suri and Vibha Datta Makhija (2013); V Mohana and Mahalakshmi Pavani (2015); Madhavi Divan, Menaka Guruswamy, Anitha Shenoy, Aparajita Singh, Aishwarya Bhati and Priya Hingorani (2019) and Rachana Srivastava (2021).

Of the 56 designated on Friday, 34 are first-generation lawyers and six are below 45 years of age. Interestingly, the five-member selection committee, for the first time, had a woman member in Kiran Suri. Other members of the committee were the CJI, Justices Sanjiv Khanna and B R Gavai, and attorney general R Venkataramani.

For the first time, the academic work of the advocates was evaluated by professors of national law universities and the assessment was included in the process for shortlisting those who had applied for the senior designation.

Interestingly, the husband-wife advocate duo of Liz Mathews and Raghent Basant got their designation as senior advocates on Friday. Among the 56 who were designated, 30 are advocates-on-record, a special category of lawyers who on passing a tough written examination qualify to file cases in the SC.

Indira Jaising was the first woman in the country to get designated as senior advocate by Bombay HC in 1986. It was on her petition that the SC passed a series of orders streamlining the process for conferring senior advocate designation.

Strikes by lawyers

2003, 2018: SC’s strict instructions against striking lawyers

Holding that irreversible damage is done to the judicial system by lawyers going on strike, the Supreme Court on Wednesday decided to act tough against erring advocates and Bar associations that passed resolutions for strike and directed the Centre to file quarterly reports on the basis of which contempt proceedings would be initiated against them.

A bench of Justices A K Goel and U U Lalit said SC declared 15 years ago lawyers could not go on strike but the order was being flouted rampantly, resulting in delays in delivery of justice.

“Since the strikes are in violation of law laid down by this court, the same amount to contempt and at least the office bearers of the associations that give call for strikes cannot disown their liability for contempt. Every resolution to go on strike and abstain from work is per se contempt.... It is necessary to provide for some mechanism to enforce the law laid down by this court, pending a legislation to remedy the situation,” the bench said.

The bench said lawyers going on strike was one of the major reason for huge pendency of cases and the time had come to deal with the problem. “By every strike, irreversible damage is suffered by the judicial system, particularly consumers of justice. They are denied access to justice. Tax payers’ money is lost on account of judicial and public time being lost,” it said.

According to the Uttarakhand HC, advocates were on strike for 455 days from 2012- 2016 (on average, 91 days per year). The figures for UP courts are the worst and the periods of strike over five years in the worst affected districts were — Muzaffarnagar (791 days), Faizabad (689 days), Sultanpur (594 days), Varanasi (547 days), Chandauli (529 days), Ambedkar Nagar (511 days), Saharanpur (506 days) and Jaunpur (510 days).

UP: lawyers strike work for over 100 days a year

State Has 51L Cases Pending In Trial Courts

Even if the strength of judicial officers were to increase from the present 18,000 to 70,000 on CJI T S Thakur's impassioned plea, the staggering pendency of over two crore cases may not be cleared in a hurry , thanks to frequent disruption of work in trial courts due to strikes by lawyers.

Uttar Pradesh has 51 lakh cases pending in trial courts, which accounts for over 25% of total pendency in all states taken together. A ground zero report given to Allahabad high court listed 10 districts where lawyers disrupted trial court work for more than 100 days on an average, every year for the last five years. Even if the number of trial court judges were increased substantially, how would they deal with how would they deal with pendency unless permitted to work by the advocates' associations, asks law commission chairman Justice B S Chauhan.

The report about the working of trial courts in Uttar Pradesh recorded the number of days that work at trial courts in the districts of Muzaffarnagar, Aligarh, Faizabad, Sultanpur, Moradabad, Mathura, Ghaziabad, Balrampur and Chandauli suffereddue to lawyers' strikes between March 1, 2010 and March 31, 2015.

The five-year data is an eye-opener. In Muzaffarnagar, a total of 753 days was lost due to lawyers' strike, which means an average of 150 days a year. In Aligarh, it was 697 days (140 days a year), Agra 696 days (140 days every year), Faizabad 693 days, Sultanpur 603 days, Moradabad 596 days, Mathura 591 days, Ghaziabad 573 days, Balrampur 560 days and Chandauli 524 days.

After discounting weekly and religious holidays, trial courts generally work for an average 250 days a year. If over 100 days are lost due to advocates' strike, it is understandable why the pendency monster refuses to be tamed.

The report prepared by the Allahabad HC, which is now also with the law commission, gave reasons why advocates struck work. The report said: “The registry of the high court has also collected information from the district judges regarding reasons of strikes in their respective districts, which are based on resolutions passed by the bar associations.“

It named a few of them, It named a few of them, which ranged from bomb blast in Army school in Pakistan to lawyers getting tired due to Republic Day programme, rainy day , death of the mother of colleague advocate and moral support to Anna Hazare's movement.

In addition to this, the report said: “Some of the common causes for the strikes in all districts of UP in the last five years are: non-declaration of holidays like Agrasen Jayanti, Basant Panchami, Nagpanchami, Budh Purnima, Bharat Milap, Saraswati Puja, Guru Teg Bahadur Singh Jayanti, Guru Govind Singh jayanti, Makar Sankranti, Ashtami Puja, birth day of Hazrat Mohammad Sahab, Holi Milan and Kavi Sammelan.“

The panel which prepared the report said it found that lawyers resorted to strike on unacceptable and flimsy grounds. “In most of the districts, the strike is virtually institutionalised. Often these strikes are called for some specific actions, where a group of lawyers either does not want a particular case to be taken up or they desire a particular matter to be adjourned.“

See also

Lawyers: India