Nagpur District, 1908

Contents |

Nagpur District, 1908

This article has been extracted from THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908. OXFORD, AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. |

Note: National, provincial and district boundaries have changed considerably since 1908. Typically, old states, ‘divisions’ and districts have been broken into smaller units, and many tahsils upgraded to districts. Some units have since been renamed. Therefore, this article is being posted mainly for its historical value.

Physical aspects

District of the Central Provinces, lying between 20° 35' and 21° 44' N. and 78° 15’ and 79° 40' E., in the plain to which it gives its name at the southern base of the Satpura Hills, with an area of 3,840 square miles. It is bounded on the north by Chhindwara and SeonT ; on the east by Bhandara ; on the south and west by Chanda and Wardha ; and along a small strip on the north-west by the AmraotI District of Berar. The greater part of Nagpur District is an undulating plain, but it is traversed by low hill ranges. In the north a strip of the Satpura Hills is included within its limits, narrow on the west but widenmg to a breadth or 12 miles or more towards the east. Immediately south of them lies the western extremity of the Ambagarh hills, on which stand the well-known temples of Ramtek. On the western border another low range of hills runs down the length of the District, and, after a Ijreak formed by the valley of the Wunna river, continues to the south-east past Umrer, cutting off on its southern side the valley of the Nand. A third small range called the Pilkapar hills crosses the Katol idhsil from north to south. There are also a few detached hills, notably that of SIta- BALDI in Nagpiir city, which is visible for a long distance from the country round. The hills attain no great altitude, the highest peaks not exceeding 2,000 feet, but vary greatly in appearance, being in places extremely picturesque and clothed with forest, while elsewhere they are covered by loose stones and brushwood, or are wholly bare and arid. The Wardha and wainganga rivers flow along part of the western and eastern borders respectively, and the drainage of the District is divided between them. The waters of about a third of its area on the west are carried to the Wardha by the Jam, the Wunna, and other minor streams. The centre is drained by the Pench and Kanhan, which, flowing south through the Satpura Hills, unite just above Kamptee, where they are also joined by the Kolar ; from here the Kanhan carries their joint waters along the northern boundary of the Umrer tahsil to meet the Wainganga on the Bhan- dara border. To the east a few small streams flow direct to the Wainganga. The richest part of the District is the western half of the Katol tahsil, cut off by the small ranges described above. It possesses a soil profusely fertile, and teems with the richest garden cultivation. Beyond the Pilkapar hills the plain country extends to the eastern border. Its surface is scarcely ever level, but it is closely cultivated, abounds in mango-groves and trees of all sorts, and to- wards the east is studded with small tanks, which form a feature in the landscape. The elevation of the plain country is from 900 to 1,000 feet above sea-level.

The primary formation of the rocks is sandstone, associated with shale and limestone. The sandstone is now covered by trap on the west, and broken up by granite on the east, leaving a small diagonal strip running through the centre of the District and ex- panding on the north-west and south-east. The juxtaposition of trap, sandstone, and granite rocks in this neighbourhood invests the geology of Nagpur with special interest.

The forests are mainly situated in a large block on the Satpura Hills to the north-east, while isolated patches are dotted on the hills extending along the south-western border. The forest growth varies with the nature of the soil, saj (Terminalia tomentosa), achar (Biicha- nania latifolid), and tetidJi (Diospyros fomentosa) being characteristic on the heavy soils, teak on good well-drained slopes, salai (BoswelHa serrata) on the steep hill-sides and ridges, and satin-wood on the sandy levels. In the open country mango, mahiia (Bassia latifolia), tamarind, and bastard date-palms are common.

There is nothing noteworthy about the wild animals of the District, and from the sportsman's point of view it is one of the poorest m the Province. Wild hog abound all over the country, finding shelter in the large grass reserves or groves of date-palm. Partridges, quail, and sand-grouse are fairl)- common ; liustard are frequentl)' seen in the soutli, and florican occasionally. Snipe and duck are obtained in the cold season in a few localities.

Nagpur has the reputation of being one of the hottest places in India during the summer months. In May the temperature rises to ii6°, while it falls on clear nights as low as 70°. During the rains the highest day temperature seldom exceeds 95°, and the lowest at night is about 70°. In the cold season the highest temperature is between 80° and 90°, and the lowest about 50 degree . Except for three months from April to June, when the heat is intense, and in Septem- ber, when the atmosphere is steamy and the moist heat very trying, the climate of Nagpur is not unpleasant.

The annual rainfiiU averages 46 inches, but less is received in the west than in the east of the District. Complete failure of the rain- fall has in the past been very rare ; but its distribution is capricious, especially towards the end of the monsoon, when tlie fate of tlir harvest is in the balance.

There is no historical record of Nagpur prior to the commence- ment of the eighteenth century, when it formed part of the Gond kingdom of Deogarh, in Chindwara. Bakht Buland, the reigning prince of Deogarh, proceeded to Delhi, and, appreciating the advantages of the civilization which he there witnessed, determined to set about the development of his own terri- tories. To this end he invited Hindu artificers and husbandmen to settle in the plain country, and founded the city of Nagpur. His successor, Chand Sultan, continued the work of civilization, and re- moved his capital to Nagpur. On Chand Sultan's death in 1739 there were disputes as to the succession, and his widow invoked the aid of Raghuji Bhonsla, who was governing Kerar on behalf of the Peshwa. The Bhonsla femily were originally headmen of Deorn, a village in the Satara District of Bombay, from which place their present representative derives his title of Rajn. Raghuji's grand- father and his two brothers had fought in the armies of Sivaji, and to the most distinguished of them was entrusted a high military command and the collection of c/iai//h in Berar. Raghuji, on being called in by the contending Gond factions, replaced the two sons of Chand Sultan on the throne from which they had been ousted by a usurper, and retired to lierar with a suitable reward for his assistance. Dissensions, however, broke out between the brothers ; and in 1743 Raghuji again intervened at the request of the elder brother, and drove out his rival. But he had not the heart to give back a second time the country he held within his grasp. Burhan Shah, the Gond Raja, though allowed to retain the outward insignia of royalty, became practically a state j)ensioner; and all real power passed to the Marathas. Bold and decisive in action, RaghujT was the type of a Maratha leader ; he saw in the troubles of other states an opening for his own ambition, and did not even require a pre- text for plunder and invasion. Twice his armies invaded Bengal, and he obtained the cession of Cuttack. Chanda, Chhattlsgarh, and Sambalpur were added to his dominions between 1745 and 1755, the year of his death. His successor Janoji took part in the wars between the Peshwa and Nizam ; and after he had in turn betrayed both of them, they united against him, and sacked and burnt Nagpur in 1765, On Janoji's death his brothers fought for the succession, until one shot the other on the battle-field of Panchgaon, 6 miles south of Nagpur, and succeeded to the regency on behalf of his infant son Raghuji 11. who was Janoji's adopted heir. In 1785 Mandla and the u])per Narbada valley were added to the Nagpur dominions by treaty with the Peshwa. Mudhoji, the regent, had courted the favour of the British, and this policy was continued for some time by his son Raghuji II, who acquired Hoshangabad and the lower Narbada valley. But in 1803 he united with Sindhia against the British Government. The two chiefs were decisively defeated at Assaye and Argaon; and by the Treaty of Deogaon of that year Raghuji ceded to the British Cuttack, Southern Berar, and vSambalpur, the last of which was, however, relinquished in 1806.

To the close of the eighteenth century the Maratha administration had been on the whole good, and the country had prospered. The first four of the Bhonslas were military chiefs with the habits of rough soldiers, connected by blood and by constant familiar intercourse with all their principal ofificers. Descended from the class of cultivators, they ever favoured and fostered that order. They were rapacious, but seldom cruel to the lower classes. Up to 1792 their territories were rarely the theatre of hostilities, and the area of cultivation and revenue continued to increase under a fairly equitable and extremely primitive system of government. After the Treaty of Deogaon, however, all this was changed. Raghuji had been deprived of a third of his territories, and he attempted to make up the loss of revenue from the remainder. The villages were mercilessly rack-rented, and many new taxes imposed. The pay of the troops was in arrears, and they maintained themselves by plundering the cultivators, while at the same time commenced the raids of the Pindaris, who became so bold that in 181 1 they advanced to Nagpur and burnt the suburbs. It was at this time that most of the numerous village forts were built, to which on the approach of these marauders the peasant retired and fought for liare life, all he possessed outside the walls being already lost to him.

On the death of Raghuji II in 181 6, his son, an imbecile, was soon supplanted and murdered by the notorious Mudhoji or Appa Sahib. A treaty of alliance providing for the maintenance of a subsidiary force by the British was signed in this year, a Resident having been appointed to the Nagpur court since 1799. In 181 7, on the outbreak of war between the British and the Peshwa, Appa Sahib threw off his cloak of friendship, and accepted an embassy and title from the Peshwa. His troops attacked the British, and were defeated in the brilliant action at SitabaldT, and a second time round Nagpur city. As a result of these battles, the remaining portion of Berar and the territories in the Narbada valley were ceded to the British. Appa Sahib was rein- stated on the throne, but shortly afterwards was discovered to be again intriguing, and was deposed and forwarded to Allahabad in custody. On the way, however, he corrupted his guards, and escaped, first to the Mahadeo Hills and subsequently to the Punjab. A grandchild of Raghuji n was then placed on the throne, and the territories were administered by the Resident from 181 8 to [830, in which year the young ruler known as RaghujT HI was allowed to assume the actual government. He died without heirs in 1853, and his territories were then declared to have lapsed. Nagpur was administered by a Com- missioner until the formation of the Central Provinces in i86r. During the Mutiny a scheme for a rising was formed by a regiment of irregular cavalry in conjunction with the disaffected Muhammadans of the city, but was frustrated by the prompt action of the civil authorities, sup- ported by Madras troops from Kamptee. Some of the native officers and two of the leading Muhammadans of the city were hanged from the ramparts of the fort, and the disturbances ended. The aged princess Baka Bai, widow of Raghuji H, used all her influence in support of the British, and largely contributed by her example to keep the Maratha districts loyal.

In several localities in the District are found circles of rough stones, occasionally extending over considerable areas. Beneath some of them fragments of pottery, flint arrow-heads, and iron implements, evidently of great antiquity, have been discovered. These were constructed by an unknown race, but are ascribed by the people to the pastoral Gaolls, and are said to be their encampments or burial-places. The remains of the fort of ParseonI, constructed of unhewn masses of rock, which are also ascribed to the Gaolls, certainly date from a very early period. The buildings at Ramtkk, Katol, Kelod, and Saonf.r are separately described. Other remains which may be mentioned are the old Gond fort of Bhiugarh on the Pench river, and the temples of Adasa and Bhugaon, and of Jiikhapur on the Saoner road.

Population

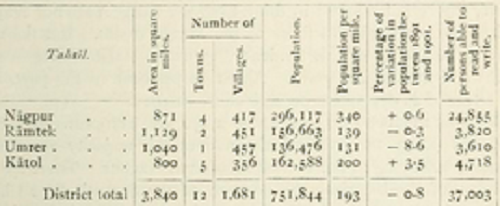

The population of the District at the last three enumerations was as Follow (1881) 0 697,356; (1891) 757,863; (1901) 751,844. Between i88r and 1891 the increase was nearly 9 per cent., the District having been generally prosperous. During the last decade the population has been almost stationary. The number of deaths exceeded that of births in the years 1894 to 1897 inclusive, and also in 1900. There was a considerable loss of popula- tion in the wheat-growing tracts of Nagpur and Umrer, while the towns and the cotton lands of Katol showed an increase. There are twelve towns— -Nagpur City, the District head-quarters, Kamptee, Umrer, Ramtek, Narkher, Khapa, Katol, Saoxer, Kalmeshwar, Mohpa, Kelod, and Mowar — and i,6Si inhabited villages. The urban popu- lation amounts to 32 per cent, of the total, which is the highest proportion in the Province. Some of the towns are almost solely agricultural, and these as a rule are now declining in importance. But others which are favourably situated for trade, or for the establishment of cotton factories, are growing rapidly. The following table gives the principal statistics of population in 1901 : —

About 88 per cent, of the population are Hindus, nearly 6 per cent. Muhammadans, and 5 per cent. Animists. There are 2,675 Jains and 481 Parsis. Three-fourths of the Aluhammadans live in towns. Many of them come from Hyderabad and the Deccan, and thev are the most turbulent class of the population. About 77 per cent, of the population speak MarathI, 9 per cent. Hindi, 51/2 per cent. Gondi, 5 per cent. Urdu, and I per cent. Telugu. It is noteworthy that nearly all the Gonds were returned at the Census as retaining their own vernacular.

The principal landholding castes are Brahmans (23,000), Kunbis (152,000), and Marathas (11,000). The Maratha Brahmans naturally form the large majority of this caste, and, besides being tVie most ex- tensive proprietors, are engaged in money-lending, trade, and the legal profession, and almost monopolize the better class of appointments in Government service. The KunbTs are the great cultivating class. They are plodding and patient, with a strong affection for their land, but wanting in energy as compared with the castes of the northern Districts. The majority of the villages owned by Marathas are included in the estates of the Bhonsla family and their relatives. A considerable pro- portion of the Government political pensioners are Marathas. Many of them also hold villages or plots : but as a rule they are extravagant in their livinc;, and several of tlie old Maraiha nobility have fallen in the world. 'I'he native army does not attract them, and but few are sufKiciently well educated for the more dignified posts in the civil employ of Government. Raghvis (12,000), LodhTs (8,000), and Kirars (4,000), representing the immigrants from Hindustan, are exceptionally good cultivators. The Kirars, however, are much given to display and incur extravagant expenditure on their dwelling-houses and jewellery, while the Lodhls are divided by constant family feuds and love of faction. There are nearly 46,000 Gonds, constituting 6 per cent, of the population. They have generally attained to some degree of civilization, and grow rice instead of the light millets which suffice for the needs of their fellow tribesmen on the Satpuras. The menial caste of Mahars form a sixth of the whole population, the great majority being cultivators and labourers. The rural Mahar is still considered as impure, and is not allowed to drink from the village well, nor may his children sit at school with those of the Hindu castes. But there are traces of the decay of this tendency, as many Mahars have become wealthy and risen in the world. About 58 per cent, of the population were returned as dependent on agriculture in 1901.

Christians number 6,163, ^f whom 2,870 are Europeans and Eura- sians, and 3,293 natives. Of the natives the majority are Roman Catholics, belonging to the French Mission at Nagpur. There are also a number of Presbyterians, the converts of the Scottish Free Church Mission. Nagpur is the head-quarters of a Roman Catholic diocese, which supports high and middle schools for European and Eurasian children and natives, and orphanages for boys and girls, the clergy being assisted by French nuns of the Order of St. Joseph who live at Nagpur and Kamptee. A mission of the Free Church of Scotland maintains a number of educational and other institutions at Nagpur and in the interior of the District. Among these may be mentioned the Hislop aided college, several schools for low-caste children, an orphanage and boarding-school for Christian girls, and the Mure Memorial Hospital for women. A small mission of the Church of England is also located at Nagpur, and one of the Methodist Episcopal Church at Kamptee.

Agriculture

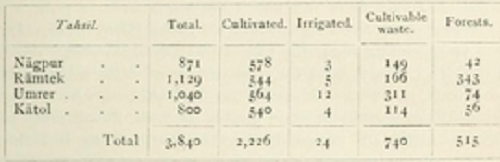

The prevailing soil is that known as black cotton. It seldom attains to a depth of 12 feet, and is superimposed on a band of conglomerate and brown clay. Rich black clay is found only in very small quantities, and the commonest soil is a dark loam mixed with limestone pebbles and of considerable fertility. The latter covers 65 per cent, of the cultivated area ; and of the remainder, 27 per cent, consists of an inferior variety of the same soil, very shallow and mixed with gravel or sand, and occurring principally in the hilly country. Little really poor land is thus under cultivation. About 383 square miles are held wholly or partially free of revenue. and 2,500 acres of Government land have been settled on the ryotwdri system. The balance of the District area is held on the ordinary mdlgiizdri tenure. The following table shows the principal statistics of cultivation in 1903-4, areas being in square miles : —

Jowar and cotton are the principal crops, covering (either alone or mixed with the pulse arhar) 661 and 633 square miles respectively. Of other crops, wheat occupies 353 square miles, til 84 square miles, linseed 132 square miles, and gram 31 square miles. Cotton and joivdr are grown principally in the west and centre of the District, rice in the east, where the rainfall is heavier, and wheat, linseed, and gram in the centre and south. The main feature of recent years is the increase in the area under autumn crops, cotton and jowar, which are frequently grown in rotation. The acreage of cotton alone and cotton with arhar has more than doubled since 1864, and that of joivdr alone and joivdr with arhar has risen by 23 per cent. This change is to be attri- buted mainly to the high prices prevailing for cotton, and partly also to the succession of unfavourable spring harvests which have lately been e.xperienced. Wheat shows a loss of 146 square miles and linseed of 106 during the same period. There are two principal varieties of cotton, of which that with a very short staple but \ielding a larger supply of lint is generally preferred. Cotton-seed is now a valuable commercial product. The recent years of short rainfall have had a prejudicial effect on the rice crop, the area under which is only 22 square miles as against 50 at settlement. Most of the rice grown is transplanted. A number of profitable vegetable and fruit crops are also grown, the most important of which are oranges, which covered 1,000 acres in 1903-4; chillies, nearly 6,000 acres; castor, nearly 4,000 acres; tobacco, 450 acres; and turmeric, 170 acres. About 17,000 acres were under fodder-grass in the same year. The leaf of the betel-vine gardens of Ramtek has a special reputation, and it is also cultivated at ParseonT and Mansar, about 130 acres being occupied altogether. Kapuri pdn (betel-leaf) is grown for local consumption and bengald pdn for export.

The occupied area increased by 12 per cent, during the currency of the thirty years' settlement (1863-4), and has further increased by 3 per cent, since the last settlement (1893-5)- I he scope for yet more extension is very limited. The area of the valuable cotton crop increases annually, and more care "is devoted to its cultivation than formerly. Cotton fields are manured whenever a supply is available, and the practice of pitting manure is growing in favour. In recent years the embankment of fields with low stone walls to protect them Irom erosion has received a great impetus in the Katol tahsil. During the ten years ending 1904, Rs. 79,000 was advanced under the Land Improvement Loans Act for the construction of wells, tanks, and field embankments, and 1-77 lakhs under the Agriculturists' Loans Act.

Owing to the scarcity of good grazing grounds, the majority of the agricultural cattle are imported, only one-fourth being bred locally. The hilly country in the north of the Ramtek tahsil is the principal breeding ground. Cattle are imported from Berar, Chhindwara, and Chanda. Buffaloes are kept for the manufacture of ght. Goats arc largely bred and sold for food, while the flocks are also hired for their manure. Cattle races take place annually at Silli in Umrer, at Irsi in Ramtek, and at Sakardara near Nagpur, these last being held by the Bhonsla family. Large weekly cattle markets are held at Sonegaon, Kodamendhr, Bhiwapur, and Mohpa.

Only 24 square miles are irrigated, most of which is rice and the re- mainder vegetable and garden crops. Wheat occasionally gets a supply of water, if the cultivator has a well in his field. The District has 995 irrigation tanks and 4,302 wells. A project for the construction of a large reservoir at Ramtek, to irrigate 40,000 acres and protect a further 30,000 acres, at an estimated cost of 16 lakhs, has been sanctioned.

Forests,&c.

The Government forests extend over 515 square miles, of which nearly 350 are situated on the foot-hills of the Satpuras on both sides of the Pencil river, and 170 consist of small blocks lying parallel to the AVardha boundary, and extending from the west of Katol to the south and east of Umrer. Small teak is scattered through the first tract, mixed with bamboos on the extreme north, but in no well-defined belts. .Satin-wo(xl, often nearly pure, is found on the sandy levels. The second tract contains small but good teak in its central blocks from Katol to the railway, but poor mixed forests to the north, and chiefly scrub to the south in the Umrer hjJis'il. Owing to the large local demand, the forests yield a substantial revenue. This amounted in 1903-4 to Rs. 63,000, of which Rs. 10,000 was realized from sales of timber, Rs. 16,000 from firewood, and Rs. 26,000 from grazing.

Deposits of manganese occur in several localities, principally in the Ramtek tahsil. A number of separate mining and prospecting leases have been granted, and a light tramway has been laid by one firm from Tharsa station to waregaon and Mandri, a distance of about 15 miles. The total output of manganese in 1904 was 66,000 tons. Mines arc being worked at Mansar, Kandri, Satak, LohdongrI, Waregaon, Kachur- wahi, Mandri, Tali, and other villages. A quarry of white sandstone is worked at Silewara on the Kanhan river, from which long thin slabs well suited for building are obtained.

Trade and communications

The weaving of cotton cloths w-ith silk borders is the staple hand industry, the principal centres being Nagpur city and Unirer. (jdld and silver thread obtained from Eurhanpur is also woven into the borders. The silk is obtained from Bengal and from China through Bombay, spun mto thin thread, and is made up into different thicknesses locally. Tasar silk cocoons are received from Chhattlsgarh. A single cloth of the finest tjuality may cost as much as Rs. 150, but loin-cloths worth from Rs. 8 to Rs. 25 a pair, and siiris from Rs. 3 to Rs. 25 each, are most in demand,White loin-cloths with red borders are woven at Umrer, the thread being dyed with lac, and coloured sdrls are made at Nagpur. Cheap cotton cloth is produced by Momins or Muhammadan weavers at Kamptee and by Koshtis at Khapa. Coarse cloth is also woven by the village Mahars, hand-spun thread being still used for the warp, on ac- count of its superior strength, and is dyed and made up into carpets and mattresses at Saoner and PatansaongT. Sawargaon, Mowar, and Narkher also have dyeing industries. In 1901 nearly 13,000 persons were returned as supported by the silk industry, 39,000 by cotton hand-weaving, and 2,500 by dyeing. Brass-working is carried on at Xagpur and Kelod, and iron betel-nut cutters and penknives are made at Nagpur.

Nagpur city has two cotton-spinning and weaving mills — the Em- press Mills, opened in 1877, and the Swadeshi Spinning and ^^"eaving Company, which started work in 1892. Their aggregate capital is 62 lakhs. Nagpur also contains 12 ginning and 11 pressing factories, Kamptee 3 and 2, and Saoner 3 and 2, while one or more are situated in several of the towns and larger villages of the cotton tract. The majority of these factories have been opened within the last five )ears. They contain altogether 673 gins and %7, cotton-presses, and have an aggregate capital of 29 lakhs approximately. Nearly 1 1,000 persons were shown as supported by employment in factories in 1901, and the numbers must have increased considerably since then. The ginning and pressing factories, howcAer, work only for four or five months in the year. The capitalists owning them are principally Marwari Banias and ]^Iaratha Brahmans, and in a smaller degree Muhammadan Bohras, Parsis, and Europeans.

Raw cotton and cotton-seed, linseed, til, and wheat are the staple exports of agricultural produce. Oranges are largely exported, and an improved variety of wild plum (Zisyphus Jujuba), which is obtained by grafting. The annual exports of oranges are valued at a lakh of rupees. Betel-leaf is sent to Northern India. Yarn and cotton cloth are sent all over India and to China, Japan, and Burma by the Empress Mills, while the Swadeshi Mills find their best market in Chhattisgarh. Hand- woven silk-bordered cloths to the value of about 5 lakhs annually are exported from Nagpur city and Umrer to Bombay, Berar, and Hyderabad, the principal demand being from Maratha Brahmans. Manganese ore is now a staple export. Many articles of produce are also received at Nagpur from other Districts and re-exported. Among these may be mentioned rice from Bhandara and Chhattisgarh, timber and bamboos from Chanda, Bhandara, and Seoni, and bamboo matting from Chanda. Cotton and grain are also received from the surround- ing Districts off the line of railway. Sea-salt from Bombay is commonly used, and a certain amount is also received from the Salt Hills of the Punjab. Mauritius sugar is imported, and sometimes mixed with the juice of sugar-cane to give it the appearance of Indian sugar, which is more expensive by one pound in the rupee. Giir, or refined sugar, comes from the United Provinces, and also from Barsi and Sholapur, in Bombay. Rice is imported from Chhattisgarh and Bengal, and a certain amount of wheat from Chhindwara is consumed locally, as it is cheaper than Nagpur wheat. The finer kinds of English cotton cloth come from Calcutta, and the coarser ones from Bombay. Kero- sene oil is bought in Bombay or Calcutta according as the rate is cheaper. The use of tea is rapidly increasing all over the District. Soda-water is largely consumed, about ten factories having been estab- lished at Nagpur. woollen and iron goods come from England. A European firm practically monopolizes the export trade in grain, and shares the cotton trade with Marwari Banias and Maratha Brah- mans. Lad Banias export hand- woven cloth, and Muhammadans and Marwaris manage the timber trade. Bohras import and retail stationery and hardware, and Cutchi Muhammadans deal in groceries, cloth, salt, and kerosene oil. Kamptee has the largest weekly market, and the Sunday and wednesday bazars at Nagpur are also important. The other leading markets, including those for cattle which have already been mentioned, are at Gaori and Kelod for grain and timber, and at Mowar for grain. . A large fair is held at Ramtek in November, at which general merchandise is sold, and small religious fairs take place at Ambhora, Kudhari, Adasa, and Dhapewara.

The Great Indian Peninsula Railway from Bombay has a length of 21 miles in the District, with 3 stations and its terminus at Nagpur city. Erom here the Bengal-Nagpur Railway runs east to Calcutta, with 5 stations and 34 miles within the limits of the District. The most important trade routes are the roads leading north-west from Nagpur city to Chhindwara and Katol, the eastern road to Bhandara through Kuhi, and the north-eastern road to SeonI through Kamptee. Next to these come the southern roads through Mill to Umrer, and to Chanda through Borl, Jam, and Warora. There is some local traffic along the road to AmraotI through Bazargaon. The District has 231 miles of metalled and 74 miles of unmetalled roads, and the annual expenditure on maintenance is Rs. 99,000. The Public Works department has charge of 253 miles of road, and the District council of 52 miles. There are avenues of trees on 185 miles, Nagpur being better provided for in this respect than almost any other District in the Province. Considering its advanced state of development, the District is not very well supplied with railways, and there appears to be some scope for the construction of feeder lines to serve the more populous outlying tracts.

Famine

Nagpur District is recorded to have suffered from failures of crops in 1819, 1825-6, and 1832-3. There was only slight distress in 1869. In 1896-7 the District was not severely affected, as the Jowar, cotton, til, and wheat crops gave a fair out- turn. Numbers of starving wanderers from other Districts, however, flocked into Nagpur city. Relief measures lasted for a year, the highest number in receipt of assistance being 18,000 in May, 1897, and the total expenditure was 5 lakhs. In 1 899-1 900 the monsoon failed completely, and only a third of a normal harvest was obtained. Relief measures lasted from September, 1899, to November, 1900, 108,000 persons, or 19 per cent, of the population, being in receipt of assistance in August, 1900. The total expenditure was 19-5 lakhs. The work done consisted principally of breaking up metal, but some tanks and wells were con- structed, and the embankment of the reservoir at Ambajheri was raised.

Administration

The Deputy-Commissioner has a staff of four Assistant or Extra- Assistant Commissioners. For administrative purposes the District is divided into four tahsils, each of which has a tahsil- ddr and a naib-tahsilddr. Forests are in charge of a Forest officer of the Imperial service ; and the Executive Engineer of the Nagpur division, including Nagpur and Wardha Districts, is stationed at Nagpur city.

The civil judicial staff consists of a District Judge and five Sub- ordinate Judges, two Munsifs at Ramtek and Katol, and one at each of the other tahsils, and a Small Cause Court Judge for Nagpur city. The Divisional and Sessions Judge of the Nagpur Division has juris- diction in the District. Kamptee has a Cantonment Magistrate, invested with the powers of a Small Cause Court Judge.

Under the Maratha administration the revenue was fixed annually. The Marathas apparently retained as a standard the demand which they found existing when they received the country from the Gonds. This was called the ain jamabandi ; and at the commencement of every year an amount varying partly with the character of the previous season, and partly with the financial necessities of the central Govern- ment, was fixed as the revenue demand. Increases of revenue were, however, expressed usually as fractions on the ain jamahandi.

The local officers or kaniaishddrs, on receiving the announcement of the revenue assessed on their charge, called the pdiels or headmen of villages together and distributed it over the individual villages accord- ing to their capacity. The patel then distributed the revenue over the fields of the village, most of which had a fixed proportionate value which determined their share of the revenue. Neither headmen nor tenants had any proprietary rights, but they were not as a rule liable to ejectment so long as they paid the revenue. Under the earlier Maratha rulers the assessment was fairly equitable ; but after the Treaty of Deogaon the District was severely rack-rented, and villages were let indiscriminately to the highest bidder, while no portion of the rental was left to the patels.

At the commencement of the protectorate after the deposition of Appa Sahib, there were more than 400 villages for which no headman could be found to accept a lease on the revenue demanded. The revenue was at once reduced by 20 per cent. Culti- vation expanded during the management by the British, and some increase was obtained, the assessment being made for periods of from three to five years. During the subsequent period of Maratha govern- ment the British system was more or less adhered to, but there was some decline in the revenue due to lax administration. Many of the cultivating headmen were also superseded by court favourites, who were usually Maratha Brahmans. The demand existing immediately prior to the first long-term settlement was 8-77 lakhs.

The District was surveyed and settled in 1862-4 for a period of thirty years, the demand being fixed at 8>78 lakhs. On this occasion proprietary rights were con- ferred on the village headmen. During the currency of the thirty years' settlement, which was effected a few years before the opening of the railway to Bombay, the condition of the agricultural classes was ex- tremely prosperous. The area occupied for cultivation increased by 12 per cent., and the prices of the staple food-grains by 140 per cent., while the rental received by the landowners rose by 20 per cent. On the expiry of this settlement, a fresh assessment was made between 1893 and 1895. The revenue demand was raised to 10-57 lakhs, or by 18 per cent, on that existing before revision, Rs. 75,000 of the revenue being ' assigned.'

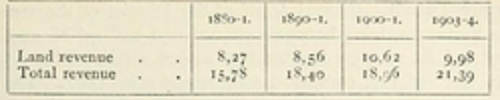

The experience of a number of bad seasons follow- ing on the introduction of the new assessment, during which the revenue was collected without difficulty, has sufficiently demonstrated its moderation. The average incidence of revenue per cultivated acre is R. 0-12-8 (maximum Rs. 1-4-ir, minimum R. 0-6), while that of the rental is Rs. 1-0-3 (maximum Rs. 1-13-10, minimum R. 0-9-1). The new settlement is for a period varying from eighteen to twenty years in different tracts. The collections of land and total revenue in recent years are shown below, in thousands of rupees : —

The management of local affairs outside municipal areas is entrusted to a District council and four local boards, each having jurisdiction over one iahsll. The income of the District council in 1903-4 was Rs. 1,05,000, while the expenditure on public works was Rs. 34,000, on education Rs. 27,000, and on medical relief Rs. 6,000. Nagpur, Ramtek, Kh.apa, Kalmeshwar, Umrer, Mowar, and S.\oner are municipal towns.

The police force — under a District Superintendent, who is usually aided by an Assistant Superintendent — consists of 1,006 officers and men, with a special reserve of 45. There are 2,130 village watchmen for 1,693 inhabited towns and villages. Nagpur city has a Central jail, with accommodation for 1,322 prisoners, including 90 females. The daily average number of prisoners in 1904 was 710. Printing and binding, woodwork (including Burmese carving), cane-work, and cloth- weaving, are the principal industries carried on in the jail.

In respect of education the District stands third in the Province, nearly 5 per cent, of the population (9-2 males and 0-7 females) being able to read and write. The percentage of children under instruction to those of school-going age is 14. Statistics of the number of pupils are as follows: (1880-1) 10,696, (1890-1) 12,394, (1900-1) 14,991, (1903-4) 14,141, including 1,135 girls. The educational institutions comprise two Arts colleges, both at Nagpur city, with 170 students, one of these, the Morris College, also containing Law classes with 42 students; 5 high schools, 16 English middle schools, 17 vernacular middle schools, and 147 primary schools. The District also contains two training schools and four other special schools. The expenditure on education in 1903-4 was 1-74 lakhs, of which i lakh was derived from Provincial and Local funds, and Rs. 30,000 from fees.

The District has 17 dispensaries, with accommodation for 201 in- patients. In 1904 the number of cases treated was 270,025, of whom 1,905 were in-patients, and 6,560 operations were performed. The expenditure was Rs. 40,000. Nagpur city also contains a lunatic asylum with 142 inmates, a leper asylum with 30 inmates, and a veterinary dispensary.

Vaccination is compulsory only in the municipal towns of Nagpur, Umrer, and Ramtek. The number of persons successfully vaccinated in 1903-4 was 33 per 1,000 of the District population, [R. H. Craddock, Setikmetit Report (1899). A District Gazetteer is being compiled.]

See also

Nagpur District, 1908

Nagpur district: Archaean Rocks

Nagpur district: The Satpuda Hills: