Nuclear weapons testing: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

From the archives of The Times of India

April 10, 2013

They are hostile neighbours widely seen by many as competing to have a bigger nuclear arsenal. However, after its first nuclear test in 1974, India offered to share nuclear technology with Pakistan. In her statement to Parliament after the tests on July 22, then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi said she had told her Pakistani counterpart, Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, that New Delhi would be ready to share the relevant technology with Islamabad. Quoting her statement, the US embassy reported, as revealed by Wikileaks, “I have explained in my letter to Prime Minister Bhutto the peaceful nature and the economic purposes of this experiment and have also stated that India is willing to share her nuclear technology with Pakistan in the same way she is willing to share it with other countries, provided proper conditions for understanding and trust are created. I once again repeat this assurance.”

Sanjay, Rajiv vied to bag IAF deals

Rajiv and Sanjay Gandhi may have, during the Emergency, vied with each other as representatives in at least one of the most rewarding IAF contracts, US Embassy cables released by WikiLeaks suggest. While Maruti, controlled by Sanjay, was negotiating for British Aircraft Corporation to land two IAF contracts, Rajiv was working for Saab-Scania, whose Viggen aircraft was in the fray with Jaguar for one of the two projects.

Gandhi was bemused by int’l fallout after Pokhran

Indira Gandhi’s offer to share nuclear technology with Pakistan was extraordinary in its audacity, but equally in its foresight. The Indian offer came as her Pakistani counterpart Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto termed as insufficient Gandhi’s assurance that tests were not meant to harm Pakistan. In his response to Gandhi, Bhutto said, many past assurances from India “regrettably remain unhonored”. Testing a nuclear device is no different from detonation of a nuclear weapon, he wrote.

Pakistan first tested a nuclear weapon in May 1998 — a fortnight after India conducted its second nuclear test. But Gandhi’s offer to share nuclear technology with Pakistan was not the move of a potential nuclear proliferator. Instead, it showed the confidence of a leader who probably believed that India, after the test, could seamlessly become part of the international nuclear system, where New Delhi could become a legitimate nuclear supplier. Gandhi’s confidence, as it turned out, was misplaced. India was immediately placed under a tough technology denial regime. In fact, the Nuclear Suppliers Group was created as a result of the test precisely to keep countries like India beyond the pale. It took a hard-fought nuclear deal with the US to open that door for India in 2008.

But on July 22, 1974, Gandhi was looking ahead, and wanted to ensure that the craters formed by nuclear explosions could be used for strategic storage of oil and gas or even shale oil extraction. In her statement to Parliament, she seemed bemused by the international reaction to the first Pokharan test. “It was emphasized that activities in the field of peaceful nuclear explosion are essentially research and development programmes. Against this background, the government of India fails to understand why India is being criticized on the ground that the technology necessary for the peaceful nuclear explosion is no different from that necessary for weapons programme. No technology is evil in itself: it is the use that nations make of technology which determines its character. India does not accept the principle of apartheid in any matter and technology is no exception.”

‘Smiling Buddha’

Omkar Gokhale, May 28, 2023: The Indian Express

Kiren Rijiju was dropped as Union minister for law and justice and replaced by Arjun Ram Meghwal. Rijiju has been assigned charge of the Ministry of Earth Sciences. He took over as the law and justice minister on July 8, 2021.

However, over the last six months, Rijiju has been at the forefront of the tussle between the central government and the Supreme Court collegium over several issues.

In the battle that played out through the speeches and court proceedings in Mumbai since November last year, Rijiju took on the judiciary on several issues and received a response from the judiciary.

On November 4, stating that the collegium system of appointing judges is “opaque” and “not accountable”, Rijiju said he had to work with the present system until the government came up with an alternative mechanism. On December 14, Rijiju said in Parliament that if the Supreme Court “starts hearing bail applications…all frivolous PILs” it would add “a lot of extra burden on the court”.

In response, while delivering the Ashok H Desai memorial lecture, organised by the Bombay Bar Association in Mumbai, Chief Justice of India D Y Chandrachud on December 17 stated that citizens can have confidence in judges to be “guardians” of (their) liberties and reiterated that “no case is big or small for the courts, be it the district courts, high courts or the Supreme Court”.

CJI Chandrachud’s comment came a day after a bench of the apex court led by him remarked that “it is in the seemingly small and routine matters involving grievances of citizens that issues of the moment, both in jurisprudential and constitutional terms, emerge”.

On January 21, days after Vice-President Jagdeep Dhankhar questioned the basic structure doctrine, as laid down by the Supreme Court in the 1973 Kesavananda Bharati case, CJI D Y Chandrachud said in Mumbai that it was “like the north star,” providing invaluable guidance for the interpretation of the Constitution.

A month later, terming Rijiju’s remarks against the collegium system for appointing judges as a “diatribe”, former Supreme Court judge Rohinton Fali Nariman said in Mumbai that if the last bastion of the independent judiciary fell, the country would enter the “abyss of a new dark age”. Nariman, who was part of the Supreme Court collegium before retiring from the apex court in August 2021, also said that “sitting on names” recommended by the collegium was “deadly against democracy”.

Meanwhile, a lawyers’ organisation had filed a PIL petition in the Bombay High Court seeking action against Rijiju and Vice President Dhankhar over their public comments “showing lack of faith in the Constitution by attacking institutions, including the Supreme Court”.

However, a bench of Acting Chief Justice Sanjay V Gangapurwala dismissed the plea observing that “the credibility of Supreme Court of India is sky high and it cannot be eroded or impinged by the statements of individuals”.

The bench noted that the constitutional authorities cannot be removed by the court as suggested by the petitioner and that “fair criticism of the judgment is permissible”, adding that it was a “fundamental duty of every citizen to abide by the Constitution” and to “respect the majesty of law”.

On May 2, Rijiju, while addressing an event organised by the Bar Council of Maharashtra and Goa in Mumbai, said the Centre had not done anything to undermine the independence and authority of the judiciary ever since Narendra Modi became prime minister.

Asked whether the government was interfering in the functioning of the judiciary, Rijiju remarked on a lighter note that the question that should be asked was whether the judiciary was interfering in the government’s work.

On May 15, a Supreme Court bench led by Justice S K Kaul dismissed an appeal filed by the Bombay Lawyers Association against the high court order on its PIL against comments by Dhankhar and Rijiju.

The apex court upheld the Bombay high court’s view. “If any authority has made an inappropriate observation, then the shoulders of the Supreme Court are broad enough to deal with the same, is the correct view,” it said.

Pokhran I/ 1974

The events

Pokhran I: India's first ever hands-on with nuclear technology, May 18, 2016: India Today

From: Pokhran I: India's first ever hands-on with nuclear technology, May 18, 2016: India Today

From: Pokhran I: India's first ever hands-on with nuclear technology, May 12, 2018: India Today

The day was May 18 in the year 1974. On this day, the Indian government conducted its first nuclear test in the deserts of Pokhran, Rajasthan making it a peaceful nuclear explosion. Smiling Buddha (MEA designation: Pokhran-I) was the assigned code name of India's first successful nuclear bomb test.

With the Smiling Buddha, India became the world's sixth nuclear power after the United States, Soviet Union, Britain, France and China to successfully test out a nuclear bomb.

Here is the history and aftermath of the nuclear test:

India started its own nuclear program in 1944

Physicist Raja Ramanna expanded and supervised scientific research on nuclear weapons and was the first directing officer of a small team of scientists that supervised and carried out the tests The name Pokhran came from the place it was tested which is a city of the same name located in Jaisalmer, Rajasthan.

A team of 75 scientists and engineers, led by Raja Ramanna, PK Iyengar, Rajagopala Chidambaram and others had worked on it from 1967 to 1974

The test was a success but the aftermath of the nuclear test was not an encouraging one

The test became the center of attention as there was widespread outrage and concern over the move since this nuclear bomb was tested by the country, which was outside the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council, and the experiments took place without any warning to the international community

As a result, the US took offense to India barging into the nuclear society without any warning and then, blocked aid to India and imposed numerous sanctions

The device tested was a fission device and there had been no release of radioactivity in the atmosphere Although, India has still not joined the 1970 nuclear non-proliferation treaty, claiming that the nuclear tests were for peaceful reasons, the nuclear deal between India and the United States showed that India's status as a responsible nuclear power has been accepted by the rest of the world.

Interested in General Knowledge and Current Affairs? Click here to stay informed and know what is happening around the world with our G.K. and Current Affairs section.

To get more updates on Current Affairs, send in your query by mail to education.intoday@gmail.com

Why India conducted its first nuclear tests

May 19, 2024: The Indian Express

The Pokhran tests of 1974 were held amid secrecy. Countries such as the United States were against the idea of more nations acquiring nuclear weapons. Why did India go ahead with the tests, and what happened after them?

Then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi termed the event a “peaceful nuclear explosion”, perhaps to assuage the rest of the world and particularly the members of the United Nations Security Council’s permanent five (or P-5) members: the United States, the United Kingdom, France, China and Russia. What exactly was their opposition, and what was India’s aim behind the test? We explain.

Following the end of World War II in 1945, which led to the deaths of millions and unprecedented destruction, new global alliances and alignments emerged. The US and the USSR continued engaging in proxy wars in other countries, for ideological and economic superiority, in what was dubbed the Cold War.

With the US dropping two nuclear bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki towards the end of the war in August 1945, and the Soviet Union carrying out its own nuclear test in 1949, it was decided that certain regulations were required to prevent massive devastation at the hands of nuclear weapons.

To maintain a kind of minimal peace, one such treaty was signed in 1968, called the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT). Nuclear-weapon States parties under the NPT are defined as those that manufactured and exploded a nuclear weapon or other nuclear explosive devices before January 1, 1967, effectively meaning the P-5 countries.

Firstly, its signatories agreed not to transfer either nuclear weapons or nuclear weapons technology to any other state. Second, the non-nuclear states agreed that they would not receive, develop or otherwise acquire nuclear weapons.

All of the signatories agreed to submit to the safeguards against proliferation established by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). Parties to the treaty also agreed to help end the nuclear arms race and limit the spread of the technology.

Why did India choose to conduct nuclear tests?

India objected to this treaty on the grounds that it was discriminatory to countries except the P-5. As foreign policy researcher Sumit Ganguly wrote, “The government of India refused to accede to the terms of the treaty because it failed to address India’s misgivings”, specifically, the fact that non-nuclear states’ pledge to not develop such weapons was not linked to any such definite obligation on part of the states already possessing nuclear weapons.

Domestically, Indian scientists Homi J Bhabha and Vikram Sarabhai had laid the groundwork earlier for nuclear energy to be tested in India. In 1954, the Department of Atomic Energy (DAE) was founded, with Bhabha as director.

An early proponent of nuclear energy, Bhabha once wrote, “Moreover, when nuclear energy has been successfully applied for power production in say a couple of decades from now, India will not have to look abroad for its experts but will find them ready at hand.” But Prime Minister Jawahar Lal Nehru continued being skeptical of nuclear weapons and expanding arms acquisition in general.

A change of leadership in the 1960s (with the death of PM Nehru and his successor Morarji Desai), a war with China in 1962 that India lost, and wars with Pakistan in 1965 and 1971, both won by India, changed the direction of India’s plans. China also conducted its nuclear tests in 1964.

How did Pokhran-I happen?

Unlike Nehru, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi did not hold a negative view of nuclear tests. But given the treaties that the P-5 had in place, India decided to conduct its tests without any prior information being released to the world.

There was uncertainty even till the end, according to an account detailed by political commentator Inder Malhotra in The Indian Express. “Raja Ramanna, the mastermind of the venture [Atomic Energy Commission Chairman], two of Indira Gandhi’s top advisers, PN Haksar and PN Dhar, were opposed to it, and wanted it postponed. Homi Sethna, chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission, offered no opinion. D Nag Chaudhuri, Scientific Adviser to the Defence Minister, started weighing pros and cons but was cut short by the prime minister. ‘Dr. Ramanna,’ she said, turning to him, ‘please go ahead. It would be good for the country’. The next morning, the Buddha smiled,” he wrote.

A nuclear device was detonated, with a yield of 12-13 kiloton of TNT, on May 18, 1974. Pokhran, an army test range located in the desert of western Rajasthan, was chosen. A team of around 75 researchers and scientists were involved. Its code name came from the test’s date being on the same day as Buddha Jayanti, the birth date of Gautam Buddha.

And what happened after the tests?

India demonstrated to the world that it could defend itself in an extreme situation and chose not to immediately weaponise the nuclear device it tested at Pokhran. This was to happen only after 1998’s Pokhran-II tests.

But before that, it would face significant criticism from many countries.

In 1978, US President Jimmy Carter signed the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Act, following which the US ceased exporting nuclear assistance to India. The US view on India testing such technologies would only shift on July 18, 2005, when US President George W Bush and Prime Minister Manmohan Singh first announced their intention to enter into a nuclear agreement in Washington.

The US also pushed for setting up a club of nuclear equipment and fissile material suppliers. The 48-nation Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG) would go on to implement agreed rules for exporting nuclear equipment, with a view to controlling the spread of nuclear weapons and where members would be admitted only by consensus.

India has been trying, since 2008, to join the group, which would give it a place at the high table where the rules of nuclear commerce are decided — and, eventually, the ability to sell equipment. Many countries that initially opposed its entry, like Australia, have changed stance; Mexico and Switzerland are the latest to voice support. India’s effort has been to chip away at the resistance, leaving only one holdout — China.

This was one reason as to why India did not immediately go for the next step, that of the testing a nuclear bomb, doing so only in 1998. Then too, the international reaction was critical, but over the years India has projected itself as a “responsible” owner of these weapons, allowing acceptance among countries and into groups like the NSG.

Nixon Caught Off-Guard By the 1974 Nuclear Test

From: Srinivas Laxman, Declassified: Nixon Caught Off-Guard By India’s 1974 Nuclear Test, December 7, 2011: Asian Scientist

The Nixon administration in the 70s was caught off-guard by India’s first nuclear weapon test on May 18,1974, say declassified intelligence documents made public by the American National Security Archive.

The Nixon administration in the 70s was caught napping while India was making preparations to conduct its first nuclear weapon test at Pokhran in Rajasthan on May 18,1974. This startling revelation has been made in declassified intelligence community staff post mortem documents which were made public on December 5, 2011 by the American National Security Archive and the Nuclear Proliferation International History Project.

“India’s peaceful nuclear explosion on 18 May, 1974 caught the U.S. by surprise in part because the intelligence community had not been looking for signs that a test was in the works,” the documents state. According to the documents which number more than 20, Nixon administration policy makers had given a low priority to the Indian nuclear weapon program, with intelligence production (analysis and reporting) “falling off” during the 20 months prior to the tests. The first Indian nuclear weapon test – codenamed “Smiling Buddha” – was conducted at 8.05 a.m. on May 18, 1974 at Pokhran. Its key players were Raja Ramanna who lead the atomic bomb team, R. Chidambaram, and P. K. Iyengar.

The documents state that in early 1972, two years prior to the test, the U.S. State Department’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research (INR) had predicted that India could make preparations for an underground test without detection by the U.S. intelligence. The INR report warned that the U.S. government had accorded a “relatively modest priority to relevant intelligence collection activities,” which suggested that a concerted effort by India to conceal such preparations may well succeed.

According to the documents, the Nixon White House was focused on the Vietnam War and a grand strategy towards Beijing and Moscow. The documents also suggest that Nixon’s trip to China during that time may have also prompted India to conduct the nuclear weapon test. Significantly, the INR had prepared its India report at a time when secret sources were telling U.S. intelligence that New Delhi was about to test a nuclear device. The small spate of reports about a nuclear weapon test had such “congruity, apparent reliabity and seeming credibility” that they prompted a review of India’s nuclear intentions by INR and other American government offices. “In the end government officials could not decide whether India had made a decision to test although a subsequent lead suggested otherwise,” the documents state. Relations between New Delhi and Washington were already cool during the Nixon administration which treated India as relatively low priority.

“That India refused to sign the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) was a non-issue for Nixon and Kissinger, who had little use for the NPT and treated nuclear proliferation as less than secondary. While the State Department cautioned India against nuclear tests in the late 1970, concern did not rise to the top of the policy hill,” the documents stressed. ——

Source: The National Security Archive.

Pokhran-II

The objectives

Indrani Bagchi, Tests that made world see India in different light, May 13, 2018: The Times of India

From: Indrani Bagchi, Tests that made world see India in different light, May 13, 2018: The Times of India

Twenty years ago, a sudden late-afternoon announcement by then Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee and his national security adviser, Brajesh Mishra, shook the world. On 11th and 13th May, India conducted a set of five nuclear tests, setting the country on the road to not merely being a nuclear power, but a country deserving of a space at the global high table.

Rakesh Sood, former diplomat and someone who was involved in the post-nuclear tests diplomacy, said India had three objectives. “First was to validate new designs to ensure credibility of the nuclear deterrent as the data set from the 1974 test was limited. Second was to declare that India was now a nuclear weapon state and modify the terms of our engagement with other states accordingly. Third was to generate an acceptance of India as a responsible state with an impeccable nonproliferation record.”

The nuclear tests announcement was followed closely by a massive global outreach by India, starting with the United States.

The first response was outright condemnation issued from every multilateral platform. But in a counter-intuitive action, then foreign minister Jaswant Singh and US deputy secretary Strobe Talbott began a conversation — that led to a whole new relationship being built between US and India. As Raja Mohan, director Carnegie India says, the tests “were needed to end India’s international isolation. They provided the basis for reconciliation with the global nuclear order, and redefined our relationship with the US”.

Former NSA, Shivshankar Menon believes the tests “shook loose our relations with all major powers, US, China, even Pakistan. The world had got used to a certain kind of India. That was challenged, successfully”. Former foreign secretary S Jaishankar says the tests created one of the prerequisites for India’s aspiration to become a leading power. “The actions we took 20 years ago ensured our national security. Our responsible record and subsequent engagements ensured global understanding of our policies. That is also shown by our nuclear collaborations around the world.”

The 1998 nuclear tests began the process for the world to acknowledge India as a responsible nuclear power. It was something Indian strategists said ad infinitum, that from 1974 despite decades of economic and technological sanctions, India had remained true to the highest NPT standards despite being an NPT outlier. While harmonising itself with the global nuclear order, the tests and their aftermath ironically destroyed the prevalent “nuclear superstructure”.

Ironically, with Pakistan, the 1998 tests — Pakistan followed soon after — gave Islamabad-Rawalpindi a sense of a ‘threshold’ below which they could continue to wage a proxy war, most spectacularly during Kargil. Since then, Pakistan has taken the riskier path, developing tactical nuclear weapons, while India separated its civil and military programmes and put a nuclear doctrine in place.

Two decades on, Pokhran-II culminated in the India-US nuclear deal, membership of three of four global non-proliferation regimes and a waiver from the NSG, doors that had been closed to India.

Taking the long view, Ashley Tellis, senior fellow at Carnegie, who helped to negotiate the nuclear deal for US described the tests as “a turning point in India’s engagement with the world — long overdue, but still incomplete, investment in assuring Indian security”.

The events

India Today.in , Building up a nuclear muscle “India Today” 15/12/2016

1998

Pokhran-II

On May 13, 1998, Prime Minister Atal Behari Vajpayee announced India's new status as the world's sixth nuclear weapons armed power. Two days before the prime minister's announcement, on May 11, 'Operation Shakti' had been initiated. India had stunned-and somewhat alarmed-the world community with a series of five nuclear weapons tests. The weapons were of three different kinds-one fusion or thermonuclear weapon, two fission devices and two sub-kiloton devices-which indicated the flexibility and range of India's nuclear arsenal, slowly built up over the years. Pokhran-II was the first Indian test of a nuclear weapon since 1974. Post-1974, bomb technology had been placed on the backburner, until Pakistan came close to acquiring a nuclear weapon with Chinese assistance. Faced with the twin threats of a Chinese and Pakistani nuclear weapons arsenal and a closing global window-the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty was opened for signatures in 1996-the strategic community was left with no other option but to hit the test button.

Kalam, atomic panel differed on Pokhran-II tests: AEC chief

Srinivas Laxman, Nov 6, 2019: The Times of India

A hitherto unknown aspect of the 1998 nuclear tests at Pokhran was that Abdul Kalam, then chief of DRDO, differed with scientists at Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) about conducting a thermonuclear test (hydrogen bomb) over safety concerns.

The experiments, codenamed ‘Operation Shakti’ consisted of testing an atomic bomb, hydrogen bomb and small devices. The tests were held on on May 11 and May 13, 1998. The differences have been revealed for the first time by former AEC chief Anil Kakodkar in his autobiography, which has been co-authored with Suresh Gangotra of department of atomic energy (DAE).

Speaking to TOI on Tuesday, Kakodkar recalled that Kalam had expressed reservations about detonating a hydrogen bomb because he feared it could cause damage to the village of Khetolai, not far from the Pokhran weapon test site. Due to Kalam’s fears, Kakodkar said differences cropped up between DRDO and DAE regarding the testing of a hydrogen bomb. In his autobiography, Kakodkar says Kalam asked him for a written undertaking that the hydrogen bomb test with a yield close to 45 kiloton would not cause any damage to the village, Khetolai. “I agreed to put my neck on the block and gave a duly signed written note…,” he writes. The test was carried out successfully and there was no damage to Khetolai .

Col. Kaushik’s details

Chethan Kumar, July 15, 2018: The Times of India

From: Chethan Kumar, July 15, 2018: The Times of India

From: Chethan Kumar, July 15, 2018: The Times of India

Pokhran II: 'Cricket to trick spy satellites, billiards to keep bombs safe'

It’s been 20 years since India stunned the world with Pokhran II. It wasn’t the fact that India had nuclear technology, but the realisation that India was able to conduct these tests without the rest of the world not having a clue as to what was going on in a remote location in Rajasthan’s Jaisalmer, despite having the place under constant satellite surveillance. In an exclusive interview with Chethan Kumar, Colonel Gopal Kaushik, formerly of the 58th Engineering regiment, talks about those groundbreaking tests.

“Before we start, I want you to assure me that my location won’t be made public,” Colonel Gopal Kaushik (retired) said, sitting in his living room, somewhere in South India. Twenty years after the regiment he was commanding – the 58th Engineers Regiment – ensured the successful nuclear tests that put India on the map of nations with nuclear arms capability, he still has some untold stories.

Code named Operation Shakti, the 1998 tests in Pokhran were the second time India tested its nuclear capability, following on from the failed efforts in 1995-96 when the country had to put off the tests owing to international pressure led by the US as details of the tests got leaked.

The challenges, therefore, were many, unlike in 1974 when India under Indira Gandhi carried out the first test – code named ‘Smiling Buddha’. In 1974, India’s intention and capability were unknown, the test location preparations remained unknown, and the US did not have satellites that could keep an eye on developments around the world.

But by the time Atal Bihari Vajpayee occupied the Prime Minister’s chair, India had demonstrated that it had nuclear capability—although the 1974 tests were officially never meant for weapons—and the entire world knew of Pokhran as the test site and powerful US satellites were already in the sky.

So, when “Buddha Smiled” again on May 11 and 13 of 1998, there were a lot of stories. And, of the many stories around Operation Shakti, the most popular has been how India handed US’ Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) its significant defeat, keeping the spying agency completely in the dark.

But some of the little known facts about the tests are here: The 58th Regiment that was responsible for carrying out the tests and keeping it a secret used cricket, practically a religion in India and billiards, to deceive spying satellites and saving the bomb, respectively.

“The security of information and activities from satellites, spies on the ground and even the general public and our troops was paramount given the leaks earlier, but along with that we also had to create and maintain six shafts as opposed to one in 1974,” Kaushik said.

About a hundred scientists, led by the former chairman of the atomic commission, R Chidambaram, former Bhabha Atomic Research Centre (BARC) chief Anil Kakodkar, former president and then Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) chief APJ Abdul Kalam, and DRDO adviser K Santhanam, Kaushik and his men worked cautiously.

The 58th Regiment had a vast high security area with periphery of outer fence measuring 24 km, with an intermediate fence of 11 km and inner fence of 6 km. Everything was on a need-to -know basis as they knew that they were being watched.

From code names to decoy security posts and from carrying out work in the night and returning equipment to their spots before the satellites came back to track in the morning, the army was literally working in camouflage in extreme weather conditions—temperatures going up to 51 degrees Celsius in summers and minus three in the winters — in a place infested by snakes and scorpions.

There were plenty of challenges that gave rise to several innovations and strategies, Kaushik said, as he collected water apples from his garden tree to offer. As he washed the apples, he said that one important strategy was to make the spies and satellites believe that everything they did was routine.

“Among the things we did was routinely play cricket, although it isn’t really a troops sport like football or hockey. That was done purely to attract people to watch and mislead the satellites that nothing significant was happening in Pokhran,” Kaushik said.

There were also several innovations. “One was to channelise the sub-soil water entering and getting collected in the shafts meant for the tests. There were some shafts that were already built as early 1981, and the 58th Regiment too built shafts in record time. In one of the older shafts, at about 100 metres inside we found a lot of groundwater collected. This meant that our men had to wear special raincoats to go inside and work, which was extremely difficult given the heat. The brackish water also meant corrosion of the metal used inside the shafts. We knew we couldn’t stop the water but we had to prevent it from raining inside. So, my company commander Major (now Brigadier) Suneeth Sharma and I executed a plan, which involved creating channels at every 100 metres of the 800-odd feet shaft. The water would then collect in the well below the canteen (a storage place built to hold the bombs) that had to be pumped out every day,” he said.

But that didn’t solve the problem completely as the pumped out water could not be released onto the sand as it would have changed colour which would be observed by the satellites.

“We couldn’t let the satellites see that we were pumping out water as it would indicate activity. Therefore, we had to bury a host of pipes under the sand to carry the pumped water away from the shafts and to sand dunes as they absorbed the water,” Kaushik said.

There were several other innovations, but the one without which there would be no Operation Shakti, was the “Billiards Sticks Concept”

With most things ready, it was time to fill up the shaft, up to the level of the canteen with sand. However, the team could not just drop sandbags from the mouth of the shaft as it could potentially damage the canteen, even the bomb, with its impact. So, in January 1998, Kaushik had conducted an experiment of lowering sand bags using a cage.

“...We’d found that it took us about one minute to place one bag. We needed to place 6,000 bags, which meant it would have taken at least six or seven days if we worked normally and five days if we worked without breaks. We didn’t have that luxury as the satellites would pick it up. In 1995-96 the satellites had picked up half-a-day’s work,” he said.

When the time arrived, Kaushik and Sharma came up with the “Billiards Sticks Concept”. “The name was given later by Santhanam, as what we did was inspired by the way cue sticks used to be arranged in Billiard parlours,” Kaushik recollected.

What the team did was to arrange six metal pipes—filled with sand to make them strong—at the door of the canteen as a barricade allowing sand to be dropped from the mouth of the shaft. “We had barricaded the canteen with these pipes after the bombs were placed and then dropped the sand down. Without this, the Buddha wouldn’t have smiled again,” Kaushik said.

A lot has happened since the Summer of 1998, but the stories from Pokhran in that year never fails to capture the audience.

2017/ number of nuclear weapons tested

From: November 6, 2017: The Times of India

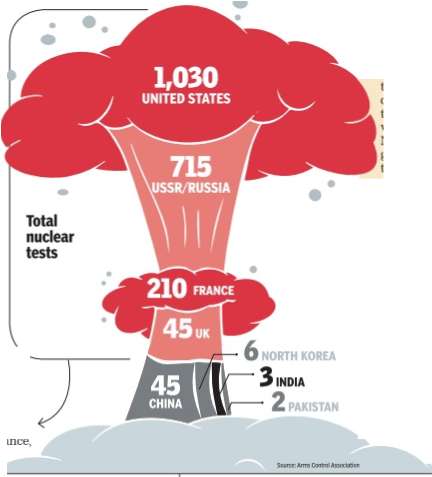

See graphic:

Nuclear weapons tested by India, Pakistan and other countries, till Nov 2017

See also

India–United States Civil Nuclear Agreement

Nuclear arsenals: India, China, Pakistan

Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG) and India

Nuclear weapons testing: India

Nuclear-powered submarine: India

And also

Pakistan- India economic relations

Pakistan- India: Cease-fire and its violations

Nuclear weapons testing: India- Pakistan

Nuclear arsenals: India, Pakistan

and many more articles, especially about the 1965 and 1971 wars, The Kargil war of 1999, 1947...