Scheduled Castes: status, issues (post-1947)

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. the Facebook community, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be acknowledged in your name. |

Links to articles already published on reputed sites/ in reputed publications may please be sent as messages to the Facebook community, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be gratefully acknowledged in your name.

Contents[hide] |

Christians, SC certificates for

Church-going dalit cannot be denied SC certificates: HC

A Subramani,TNN | Dec 27, 2013

CHENNAI: There is no rationale in denying scheduled caste (SC) certificate and other benefits to a church-going dalit, the Madras high court has said.

A division bench comprising Justice N Paul Vasanthakumar and Justice T S Sivagnanam, passing orders on a person whose application for SC certificate was rejected by a sub-collector in Puducherry, said going to church could seldom be considered a valid reason to reject the application.

"For deciding the community status, the factors that are to be verified are whether the person is suffering from any kind of social and economic disability and whether the scheduled caste Hindus in the locality are treating the person as one among themselves," they said.

Noting that the sub-collector got carried away by the VAO's report and rejected M Jayaraj alias Ramajayam's claim, the judges said: "Rejection of community/social status community certificate to deserving person will deny his valuable rights guaranteed under the Constitution and attaches civil consequences."

The report merely stated that the Jayaraj was often visiting the church in Othiyampattu village.

The judges said the sub-collector was bound to conduct a proper inquiry and could take a decision only after affording opportunity of hearing to the applicant. Pointing out that such a procedure had not been followed in the present case, they set aside the impugned order dated June 21, 2011. The court also restored the application of Jayaraj and asked the officials to consider the matter afresh and pass fresh orders within four weeks.

Education

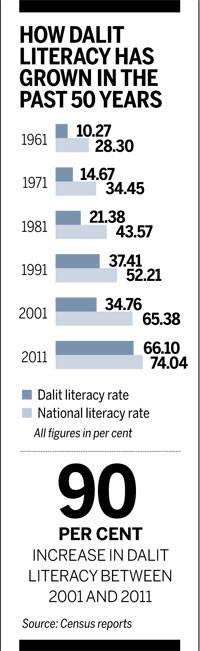

2001> 2011: Remarkable progress, but high dropout rate

The Times of India, January 24, 2016

Subodh Varma

Enrol and dropout, education is a one-way street for Dalits

The surge in education among India's most deprived communities, the dalits and adivasis, is re markable: between 2001 and 2011, the share of dalits attending college zoomed up by a staggering 187% and adivasis, by 164%. The comparable increase for all other castes put together is 119%.

So, a large number of dalits and adivasis entered colleges and universities, many of whom would have been first-generation entrants like Rohith. This is all the more remarkable considering the difficult conditions they live in 21% dalit families live in houses with thatch or bamboo roofs compared to 15% overall, 78% stay in one or two roomed houses compared to 69% overall, 35% have a drinking water source within their home compared to 47% overall, 41% do not have electricity compared to 33% overall, and 66% do not have toilets compared to 53% overall.

While school-level enrollment for all castes and communities is roughly the same, there are many more dropouts among dalits and adivasis. Among dalits, the share of school students drops from 81% in the 6-14 years age group to 60% in the 15-19 group. It plummets further to just 11% in the 20-24 age group in higher education. This fall is noticeable across communities and castes but it is the sharpest among dalits and adivasis.

According to an NSSO survey, nearly two-thirds of male dropouts from school and college said that they were needed to supplement the household income while nearly half the female dropouts said that they were needed for domestic chores. The same survey also showed that attendance rates in educational institutions were about 50% in the poorest 10% families but rose to nearly 70% in the richest 10 per cent. Poverty is thus the biggest barrier to pursuing education, and poverty levels are highest among dalits and adivasis. Besides this, these groups also face social discrimination and sometimes, abuse. At a public hearing organized by the People's Trust and CRY in Salem, Tamil Nadu, a young dalit girl, who dropped out of school, said students like her were often taunted and abused by teachers as well as students. She had started working in brick kilns or fields. Shockingly, the same atmosphere prevails in centres of higher education as incidents from various universities and the IITs show.

So, on an average, very few --about one in 10 -students at the higher levels of education are from dalit or adivasi communities. This heightens the sense of isolation among disadvantaged students. And then you have the discrimination, the high costs, the pressure to perfor m, and perhaps -as in the case of Rohith's alma mater -even official hounding.

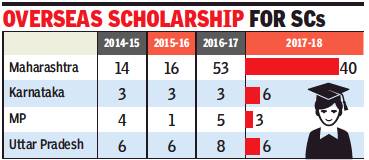

Govt. scholarships for overseas education, 2014-18

Subodh Ghildiyal, Dalits from Maha top foreign univs scholarships, July 4, 2018: The Times of India

From: Subodh Ghildiyal, Dalits from Maha top foreign univs scholarships, July 4, 2018: The Times of India

Maharashtra dominates the government scholarships given to Dalit students to pursue higher studies in foreign universities, with data of recent years showing that the state is head and shoulders above the rest.

Of the 72 fellowships awarded under ‘National Overseas Scholarship for SCs’ (NOS) till February 2018, 40 have gone to students from Maharashtra.

The contrast with other states is evident from the fact that Karnataka and Uttar Pradesh were in second place with six scholarships each.

In fact, the trend has been overwhelmingly skewed in favour Maharashtra for the last few years. Of the 108 fellowships given in 2016-17, 53 went to the western state while UP had eight and Madhya Pradesh and Tamil Nadu five each. Other states languished between 0-4 fellowships.

Maharashtra also topped the list with similar overwhelming numbers in the previous three years.

Run by the social justice ministry, the NOS funds SC students selected for pursuing masters-level courses and PhD abroad. The scheme used to have 30 seats, which was increased to 60, and further raised to 100 in 2014.

According to officials, the reason behind Maharashtra’s ability to literally corner the NOS is better educational guidance available to students. They said awareness level about the NOS was high in Maharashtra because the state also ran a similar scheme.

Sociologists attribute it to Ambedkar and his stress on education as the road to emancipation. The premium the Dalit mascot put on studies resulted in a tradition for higher education.

A group of scholarship beneficiaries who returned to work among Dalits, not willing to be named, is responsible for providing impetus to Ambedkar’s idea. They are involved in creating awareness about the overseas scholarship and providing guidance to interested students.

An expert said Maharashtra instituted its overseas scholarship scheme many years ago, which is viewed as a quality programme, while most big states with high Dalit populations do not have such a provision. It has resulted in the yawning gap in awareness levels between states.

Of the 50 NOS fellowships in 2015-16, Maharashtra bagged 16 follwed by Andhra Pradesh (5), Delhi, Punjab, Tamil Nadu (4), Assam (2), Karnataka (3), Kerala, Odisha, Rajasthan and MP (1).

Education in Scheduled Caste history, issues

2018: Bhim Pathshalas spread across UP

Ishita Bhatia, Bhim Pathshalas now mushroom across UP, April 16, 2018: The Times of India

Pupils Take Lessons On Dalit History, Icons

What had started as a two-hour coaching after school hours for Dalit children in Saharanpur due to lack of facilities in government schools — Bhim Pathshalas — has now spread across Uttar Pradesh with nearly 1,000 such classes being conducted in the state. Sometimes under the shade of a tree, and at other times in the house of a Bhim Army member, Bhim Pathshalas play a key role in teaching Dalit children about BR Ambedkar, Sant Valmiki and others to teach them about their history. Spreading slowly in the rural pockets of the state, these Pathshalas are helping strengthen the Dalit movement in UP.

“The facilities in government schools have always remained questionable. This is why the students look out for tuition classes. But since most of the Dalit students cannot afford tuitions, they tend to lag behind. To ensure that the students become educated and remain on par with others in the society, Bhim Army members came together to teach the kids. The classes are conducted for free. In fact, they are provided with free stationery items and books – the cost of which is borne by Bhim Army members, who contribute for the cause,” said Kamal Walia, Saharanpur district president, Bhim Army.

Spread in Uttar Pradesh including Saharanpur, Muzaffarnagar, Agra and others, Bhim Pathshalas are not just coaching classes for school books, though. The teachers, who are graduates and post graduates, also focus on Dalit history and tell students about the struggles and lives of Dalit icons.

“’Jo qaum apna itihaas nahi jaanti, vo qaum itihaas nahi likh sakti’ (They cannot make history, who forget history), Baba Saheb Ambedkar had said. We are just making his dreams come true by making the students aware about their history and making them educated,” said Walia.

Chandrashekhar Azad, founder of Bhim Army and the son of a former headmaster had started the schools to ensure that Dalit children did not miss on their crucial early education. Azad, who is in jail as of now, had garnered national headlines after violence broke out in Saharanpur on May 9, 2017 when Bhim Army had called a mahapanchayat against alleged atrocities on Dalits.

Vinay Ratan Singh, national president, Bhim Army said, “Bhim Army is not just a Dalit movement. It is a movement about liberal people and Bhim Pathshalas help in bringing kids together to become a part of this movement at a young age.”

Employment in the private sector, self-employed

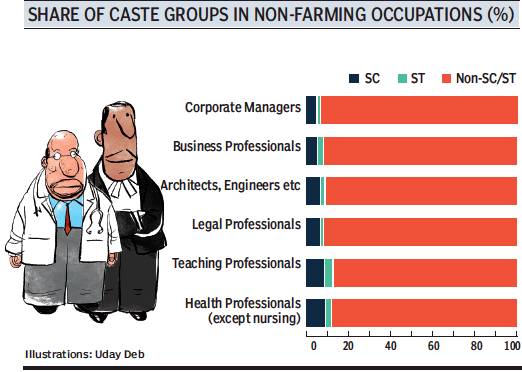

As in the 2011 census

From: Rema Nagarajan, In 21st century India, caste still decides what you do, December 22, 2018: The Times of India

From: Rema Nagarajan, In 21st century India, caste still decides what you do, December 22, 2018: The Times of India

From: Rema Nagarajan, In 21st century India, caste still decides what you do, December 22, 2018: The Times of India

Census Data Shows Low Presence Of SC/STs In Coveted Professions, High Proportion In The ‘Lowly’ Ones

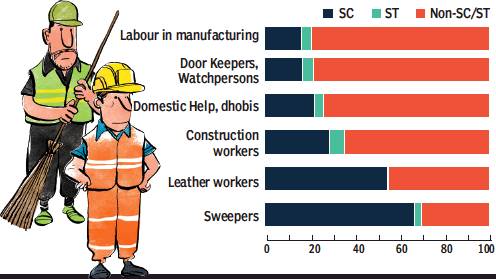

Caste continues to be one of the biggest factors that determine a person’s occupation going by the latest census data on nonfarm workers. Occupations traditionally considered as ‘lowly’, like sweeping and leather work, continue to be dominated by scheduled castes in general, more so by the specific castes associated with such work. And the jobs at the top are almost entirely in the grip of those who are not from scheduled castes or tribes.

Among coveted jobs at the top, those entirely in the private sector—corporate managers and business professionals — have the worst representation of SCs and STs. About 93% of corporate manager jobs are held by non-SC/ST people. In the case of sectors with significant government presence, such as teaching and healthcare, the scenario is much better.

It is difficult to say from the current data set how much this skew in the presence of SCs and STs in many professions is because of class — as class closely mirrors caste in India — and how much is due to actual caste discrimination. But what is amply evident is that the link between caste and occupation remains strong. Also, worryingly, the link between occupations traditionally viewed as ‘lowly’, such as sweepers and leather workers, seems to be as strong in younger age groups as in older ones.

Among the aspirational jobs that TOI looked at in the census data (see graphics), SCs have the highest proportion among teachers and healthcare professionals, 8.9% and 9.3%, respectively, though still well below their proportion of 14% in all non-farm workers. STs have proportional representation in the teaching profession in almost all states.

Another profession with representation of SCs (13.7%) and STs (9.3%) almost in proportion to their population shares is that of policemen, again totally in the government sector. In fact, STs have a representation among police personnel well over their proportion of 4% among all non-farm workers, thanks to many states with significant tribal populations taking them in large numbers into the police force.

Despite several reports of mid-day meal cooks belonging to scheduled castes facing discrimination, intriguingly, there is a fairly high proportion of SCs among cooks in several states, including Punjab (44.3%) and Uttar Pradesh (21.3%), two states generally seen as caste-ridden. Why this is the case is not clear.

Among lower rung professions, those involving hard manual labour again show a pattern of SC and ST representation well above their proportion in the non-farm worker population. In the middling professions, their presence improves considerably compared to the aspirational professions, but remains lower than their share in all non-farm jobs.

There are only two professions, leather work and sweeping, where the scheduled castes are in a majority. For instance, of the 46,000 leather workers in Uttar Pradesh, 41,000 are from castes traditionally associated with leather work — Chamars, Dhusia, Jatava, etc. Similarly, in Rajasthan, of 76,000 sweepers, almost 52,000 belong to castes such as Bhangi, Mehtar and Chura, associated traditionally with this job.

Though there are signs of SCs breaking into better jobs to some extent, in the case of castes associated with sweeping and leather work, a significant chunk is still stuck in these traditional occupations. For instance, in Uttar Pradesh, of the total number of SC persons in the 35-59 age group working as sweepers, 63.4% are Balmikis. Even in the 15-34 age group, 62% of SC sweepers are Balmikis, showing how little has changed for the new generation. Similarly, of SCs engaged in leather work in the 35-59 age group, Chamars, Dhusias, Jatavas account for 88.2%. In the 15-34 age group, too, that proportion is 88.2%. A similar pattern holds in Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan as well.

Employment obtained through exchanges

2014

From: Swati Mathur, Just 0.3% of Dalits got jobs via employment exchanges in 2014, April 4, 2018: The Times of India

Joblessness is one of the key reasons why Dalits across India took to the streets to demand that their social and economic lot be improved.

In the backdrop of widespread protests that saw nine people killed and many more injured in states like MP, Rajasthan and UP, data submitted by the government to Lok Sabha showed extremely high levels of unemployment among Dalits, lower, in fact, than employment given to tribals and minorities.

Labour minister Santosh Gangwar submitted data that showed that of the 76.44 lakh Scheduled Caste persons who registered themselves for jobs with employment exchanges in 2014, only 22,000 (0.3%) were given jobs.

However, the government has not provided employment data for subsequent years leading to the current year and said the figures are “not available”.

Attributing the gap between demand and supply of jobs, former National Commission for SCs chairman and Rajya Sabha MP P L Punia said, “Since Dalits are at the bottom of the social ladder, their employability remains lower than minorities, who are skilled and are not socially disadvantaged.”

‘Invisible Dalits’

In UP

Avijit Ghosh/ The Times of India, Jan 2017: Dalits are 21% of UP population. Badri Narayan’s new book, Fractured Tales, discusses a new sub category called invisible Dalits.

Badri Narayan elaborated:

There are almost 65 Dalit communities in UP but most know only two or three of these communities in every district. The other communities are not visible in the democratic domain. Their participation in public life, in the service sector and in the political sphere is almost negligible. Due to their lack of presence in these important domains i have referred to them as invisible communities.

Dalit castes like Musahars (rat pickers), Nats (wanderers), Basor (weavers), Bansphor (bamboo basket makers) are in fairly decent numbers but it is not enough for these communities to create pressure on the vote bank politics.Apart from them, there are many other Dalit castes in even lesser numbers like Bahelia (bird hunters), Khairha (woodcutters), Kalabaaz (singers), etc. They are not visible in any political or governance strategy. They have not even reached at the door of democracy from where they can knock at the door.

Badri Narayan |Scattered and invisible, December 15, 2016, Indian Express

Non-Jatav Dalits in UP do not find political representation because of their limited role in swaying state and national elections.

The media and political analysts discuss the possibility of the success or failure of any political party on the basis of the numerical percentage of its core voters. Statistical analysis looks at these castes and communities as a homogeneous vote bank, but in reality they are not so. The deep-rooted desire for recognition and the aspiration for political participation lure the numerically large and influential castes among Dalits and backwards to vote in favour of a particular political party. Even among these social groups, the most marginalised — which are scattered and numerically less — follow a different voting pattern.

Dalits, who comprise about 21.6 per cent of the population of Uttar Pradesh, are widely considered to form the base of the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP). On analysing the grassroot reality, we find that among the large number of Dalit castes, it is only the Jatavs who are the core voters for BSP. In addition, castes like Pasi, Dhobhi, Kori, Khatik are considered the “Bahujan voters” of the party. Among the 65 Dalit castes, more than 55 are numerically less, scattered and their presence is almost negligible. A few of them are Basor, Sapera, Kuchbadhiya, Musahar, Begaar, Tantwa, Rangrej and Sarvan. At the local level, these communities often vote under the influence of prominent Dalit, backward and savarna castes. Political parties are either unaware of their presence or do not give them much importance as they make a weak vote bank.

These numerically small castes mostly reside in hamlets comprising of 10 or 20 huts and even in large, multi-caste hamlets only two or three of their huts can be seen. Though their votes are given due importance in the panchayat elections, the same is not true during Lok Sabha and Vidhan Sabha elections. Even political parties like the BSP, which are actively involved in Dalit-Bahujan politics, take them for granted. Neither do candidates from these castes get tickets during elections nor are they provided political participation. Thus, we see such castes living in penury and existing as an invisible social group in Indian democratic politics. It is sad that even after seven decades of Independence they have not been able to become a part of our political society or received any recognition as subaltern citizens.

Though they come under the category of Dalit and Bahujan, their presence is almost negligible in Dalit and Bahujan politics. They get a minor share of the resources distributed to the poor and the marginalised. These castes do not possess their own community leaders and the political parties too are hesitant in giving them leadership roles. They are still far away from the doors of education and are economically weak to the extent that they are not able to develop their own politics. They can develop their own politics only when an economically strong group emerges from amongst their communities.

The R S S has begun some work among these groups in certain regions of UP. The Sangh is actively propagating its samrasta (harmony) programmes in villages at the border areas of UP and Nepal which extends from Gorakhpur to Bahraich, the Awadh region and some areas of eastern UP. The Sangh is organising programmes like the cleanliness of hamlets, having samrasta bhoj with residents and is also running primary schools. It is also running its shakhas in the gardens and ponds near the hamlets of marginalised Dalits and is endeavouring to produce activists from among them.

The Sangh’s work in this direction may produce activists who can take on leadership roles, but it is quite difficult to say the number of years it will take for these marginalised communities to create a place in the BJP’s politics. During my field visits, I observed that in the executive training camps organised in the areas adjoining Allahabad, the R S S is making efforts to establish a connection with the activists from the “small” Dalit castes.

The Congress is also showing an interest in associating with these castes and would like to provide political representation to the non-Jatav Dalit castes. But on coming to terms with the limited vote-share and probability of candidates from these castes winning, it may limit their political participation. The local Congress leadership is keen to get non-Jatav Dalits as voters, but they do not have a long-term policy to establish leaders from among these communities or to provide them any political recognition. BSP leaders show a keen interest is associating such castes with their party and consider them a part of the Bahujan society, yet they have done little for the political inclusion of these communities.

A major irony of Indian democratic politics is that the political value of a citizen is determined by the numerical strength of his/her caste and her/his efficiency in terms of the money and power to achieve victory during elections. Democracy has become a game in the hands of various powerful people and communities. Kanshi Ram laid the foundation of the Bahujan political structure based on the principle that “the political participation of any caste is directly proportional to its numerical strength”. Based on this principle, numerically strong Dalit castes have received political visibility and political participation — to some extent — after the development of Bahujan politics. But the fate of more than 55 Dalit and Bahujan castes, scattered in various pockets of Uttar Pradesh, is yet to be decided. This is a crucial question before our democracy, the answer for which must be found sooner rather than later.

The writer is a social scientist and author. His latest book, ‘Fractured Tales:Invisibles in Indian Democracy’, is published by Oxford University Press

Offensive names of localities/ villages

Sandeep Rai, Village names are reason for shame, Feb 22, 2017: The Times of India

Calling a Dalit by his caste name is an offence under the SCST (Prevention of Atrocities) Act. But Bundelkhand's rigid caste-based society continues to humiliate the Scheduled Castes. Here's how.

Several localities and villages spread over the region are named after the castes of people who live there. There's been a long-standing demand by Dalits to change the names of these localities. But nothing has happened, although candidates of political parties have in the past promised to implement the demand.

Barely 20km from Jhansi is Bajna village, where a large number of Dalits live in a locality called Chamarya. This term is generally associated with Dalit communities such as Jatav and Jatia. They are collectively known as `Chamaar', a prohibited term.

“Every election, we ask candidates to get the names of these villages changed, but we get empty promises.It's embarrassing when you are asked your village name.It immediately reveals our caste identity and the attitude of people around us changes drastically in this caste-driven society of Bundelkhand,“ says Budhh Prakash of Chamroa.

Deep Shikha, Chamarsena's pradhan, said, “We submitted an application to change the name of this village from Chamarsena to Amarsena but I doubt if it's been changed because no one takes us seriously in government offices.“

Owing to extreme subjugation of Dalits in the region, name change of a village or locality often becomes a matter of secondary importance.“A majority of people in these villages are illiterate and downtrodden. Politicians and their strongmen force these people to vote for specific candidates. So, the question of demanding their rights does not even arise,“ said Ganpat Kumar, a school teacher in Chamarya.

B

STATE-WISE ISSUES

Haryana

Dalit Rise Upper Castes' Envy

The Times of India, October 22, 2015

Subodh Ghildiyal

Dalit rise upper castes' envy in Haryana

Dominant Class Unable To Accept Changing Social Order In Mirchpur and Gohana, altercations between Jats and Dalits resulted in mobs razing down and burning Dalit houses, medieval style. No one died in Gohana but 50 houses were torched by a 1,000-strong mob. But Mirchpur saw a lynch mob set on fire a handicapped girl and her grandfather in their house, like Faridabad. In Sunped, Rajputs settled scores with Dalits.

At the root of the brutal crimes is the newfound independence of Dalits and a questioning of the status quo. Observers say the brutal retribution inflicted by the upper castes is aimed to deliver a strong reminder to Dalits on who dominates socially .

KaramvirBaudh, an activist in Haryana, said, “Jobs and small businesses are a growing trend among SCs. Cars and good houses in their neighbourhoods are visible. They refuse to work in landlords' fields.It is enough of a provocation.“

If the fault lines existed for ages, its incendiary eruption in medieval lynchings and immolations in the last decade re sults from fearless assertion by Dalits riding on job reservations and market economy . “The dominant peasant proprietors who were used to having their way are unable to take the resistance from Dalits.That is leading to brutality ,“ said Yogendra Yadav, a sociologist with roots in Haryana. The questioning of status quo is the trigger. And the op pressor changes with the turf, it could be Jats in Rohtak, Yadavs in Mahendragarh, Rajputs and OBC Rors in Yamunanagar.

Dr Gulshan, who heads the Ambedkar missionaries society in Rohtak, recounted how every atrocity was accompanied by the incredulous “ek SC ne aisakardiya“ -it could refer to refusal to work in landlords' fields or challenging the harassment of a Dalit girl. “In a wrestling game, the taunt is that you lost to a Dalit boy,“ he said, talking about provocation.

Sexual assault of Dalits has emerged as a new weapon to assert domination. Haryana, according to the NCRB, ranks seventh in assaults on SC women, fourth in sexual harassment, sixth in rapes.

See also

Caste-based reservations, India (history)

Caste-based reservations, India (legal position)

Caste-based reservations, India (the results, statistics)

Scheduled Caste and tribal sub-plan: India

Scheduled Caste entrepreneurs and millionaires: India

Scheduled Caste lead characters in Hindi-Urdu cinema

Scheduled caste players in Indian cricket teams

Scheduled Castes: status, issues (post-1947)