The Constitution of India: Amendments

This article has been sourced from an authoritative, official After the formal launch of their online archival encyclopædia, |

The power to amend the Constitution

Article 368 of the Constitution of India gives Parliament the power to amend the Constitution, through a procedure described by Dr. B.R. Ambedkar in the Constituent Assembly as one of the simplest in the world. For a Bill seeking to amend the Constitution to pass, it must secure a majority of the total membership of the House and a majority of not less than two-thirds of the members present and voting, in each House of Parliament. Some special cases — amendments that affect the functioning of State governments, High Courts or the Supreme Court for example — also require the ratification of half the State legislatures in the country.

Amendments to the Constitution: an overview

Grouping The important amendments into three categories

From the Times of India's archives:

The first 94 amendments can be broadly classified into three categories.

First is technical and administrative category like the increase in the retirement age of HC judges and so on.

The second category constitutes amendments to clarify the interpretation of the Constitution itself. There might be a difference in interpretation of the Constitution by government and judiciary, and hence, it is amended to make the interpretation clear.

Third, a consensus among political parties about a particular issue may also result in amendment of the Constitution.

Ronojoy Sen's view:

Of the several amendments to the Indian Constitution, all are of course not of equal importance. But like the US Constitution, the First Amendment to the Indian Constitution must rank up there as one of the most critical. It would also set in motion a series of face-offs with the judiciary over who was the final arbiter of the Constitution – Parliament or the courts. It is estimated that of the first 45 amendments to the Constitution, about half were aimed at curbing the judiciary. Indeed, the First Amendment was primarily triggered by adverse court judgments. The Madras high court and subsequently the Supreme Court had struck down a legislation which put in place a quota system in government-run medical and engineering colleges for lower castes. At around the same time the major plank of the socialist policy of theCongress government in the 1950s — land reform — was being short-circuited by high courts across the country. The last straw was when the Supreme Court upheld the right to circulate a Communist journal in Madras against the state government’s wishes.

Parliament stepped in by amending the Constitution to ensure that equality before law and provisions for ensuring caste equality did not bar legislation for providing reservation for backward classes. It also amended Article 19 – which guaranteed the fundamental right to freedom of speech among other things – by introducing “reasonable restrictions” on speech in the interests of the state.

Finally, The First Amendment inserted Article 31A in the Constitution which stipulated that nothing in the Fundamental Rights could be used to strike down laws for the appropriation of property. During the parliamentary debate on the First Amendment, Jawaharlal Nehru made the oft-quoted statement on the regressive nature of the judiciary: “Somehow we have found this magnificent Constitution we have framed, was later kidnapped and purloined by lawyers.” He added for good measure that the amendment was meant “to take away, and I say so deliberately, to take away the question of zamindari and land reform from the purview of the courts.”

10 Key Amendments

ARGHYA SENGUPTA, August 14, 2022: The Times of India

Acharya Kripalani is said to have remarked when lying ill in hospital: “I have no constitution. All that is left are amendments. ” He said this during the Emergency, at the time the 42nd Amendment to the Constitution of India was in the offing. This amendment, more like a mini-Constitution itself, changed large portions of the original constitutional text, including the Preamble and the powers of the Supreme Court.

Kripalani, like others, was apprehensive that with the amendments the Constitution would become a pale shadow of itself. However, with Indira Gandhi’s electoral defeat, the successor Janata Government enacted the 44th Amendment to undo much of the damage. These two amendments, in quick succession, demonstrated the power of the Constitution to fundamentally shape and reshape the lives of ordinary Indians.

Here are 10 constitutional amendments of the last seven decades that left their mark on democracy in India, restructured institutions of government and established the rights and responsibilities of citizens and their governments.

BACK AND FORTH ON CONSTITUTION

42nd Amendment | 1976

It was the Indira Gandhi government’s imprimatur on the Constitution of India. With lofty proclamations on the need for a “living” Constitution, it amended the Preamble to state that India would be “socialist” and “secular”. To project the image of a powerful nation, it stressed that the “integrity of the nation”, apart from its unity, would be assured. It also gave wide powers to the government to suspend fundamental rights during the Emergency, curtailed the power of high courts and set up tribunals to speed up the delivery of justice.

44th Amendment | 1978

The Morarji Desai government that succeeded Indira in 1977 moved to restore the Constitution to its pre42nd Amendment condition. It’s remarkable that the 44th Amendment, which added crucial safeguards against the deprivation of fundamental rights, curtailed the wide-ranging emergency powers of the Centre, and downgraded the right to property from a fundamental right to a constitutional right, passed despite the ruling Janata Party’s internal tensions.

52nd Amendment | 1985

Gaya Lal, an Independent MLA in Haryana, joined Congress, switched to the United Front, came back to Congress and on the same day went back to the United Front. All in the space of two weeks. The 52nd Amendment was enacted to stop such defections. It introduced the 10th Schedule disqualifying MPs and state legislators who hopped parties. Recent events, including in Maharashtra, however, have shown its limits.

61st Amendment | 1988

This amendment reduced the voting age from 21 to 18, and in one stroke added 5 crore voters for the next elections. In a speech in Parliament, PM Rajiv Gandhi declared it was “an expression of our full faith in the youth of the country”. The amendment changed India’s electoral landscape and the campaign strategies of parties for good.

FREE SPEECH LOST, EDUCATION GAINED

1st Amendment | 1951

The Constituent Assembly had to amend the Constitution within months of its coming into force after the Supreme Court severely restricted the government’s ability to restrict free speech. The SC overturned the censorship of two magazines – the left-leaning CrossRoads and the right-leaning Organiser. Under the guise of fixing the “moral problem” of “vulgarity and indecency and falsehood” which “poisoned the mind of the younger generation” Nehru supported the amendment that gave vast powers to governments to arrest citizens for expressing their views.

The unfortunate legacy of this amendment lives on.

86th Amendment | 2002

The framers of the Constitution had not made education a fundamental right because they felt the State would not have the resources to uphold this right for every child. In 2002, with the economy booming, the right to education was made a fundamental right for children aged 6-14, which led to the Right to Education Act, 2009.

103rd Amendment | 2019

The original Constitution was against granting reservation in universities and jobs on economic criteria alone. Ambedkar was clear that backwardness would have to mean both social and educational backwardness. This logic was fundamentally changed by the 103rd Amendment that provided reservation on the basis of economic criteria. Later, the family income cut-off was set at Rs 8 lakh per annum.

PANCHAYATS ADVANCE, INSTITUTIONS EVOLVE

73rd and 74th Amendments | 1992

Mahatma Gandhi was a steadfast advocate of self-contained ‘village republics’ as the basic unit of governance in independent India. The Constituent Assembly had the opportunity to formalise this idea, but the opponents of this view, led by Ambedkar, emerged victorious. Ambedkar said Indian villages were a “sink of localism, a den of ignorance, narrow-mindedness and communalism”. But 40 years on, in 1991, the Union government introduced and passed the 73rd and 74th Amendments mandating the creation of panchayats

and municipalities in every state. These amendments decentralised governance and administration in India and increased the involvement of the community in planning and implementing schemes, at least on paper.

99th Amendment | 2014

On New Year’s Eve in 2014, the Modi government’s first major constitutional amendment changed the method of appointment of judges to the Supreme Court and high courts. The National Judicial Appointments Commission, a longstanding demand of all political parties, was brought in by consensus to bring to an end the opaque system of appointments led by a collegium of senior Supreme Court judges. In a controversial judgment, the SC struck down the amendment for violating the basic structure of the Constitution. With reasoning that was altogether tenuous, it underlined the need for judicial independence which could only be protected by judges themselves. Recent history has shown otherwise.

101st Amendment | 2016

Indian federalism espoused the principle that states and the Union were sovereign in their own respects. The 101st Amendment changed that fundamental understanding when the Union and the states pooled their sovereignty to enact the Goods and Services Tax – a single indirect tax for the entire country, bringing simplicity and ease of living for Indians. Addressing a joint session of Parliament to usher in GST, then finance minister Arun Jaitley described it as one of “India’s biggest and most ambitious tax and economic reforms in history” that would awaken India to “limitless possibilities”. Sengupta is Research Director, Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy

Amendments were foreseen

From the archives of The Times of India 2007, 2009

India’s Living Constitution

' Ronojoy Sen

It has been amended 94 times since it was adopted in 1949, often in an attempt to curb the judiciary. And yet, as the aftermath of the Emergency showed, reckless tampering with the Constitution can backfire on governments

A day before the Indian Constitution was formally adopted on November 26, 1949 after nearly three years of intense deliberations, Bhim Rao Ambedkar delivered one of his finest speeches. Summing up the work of the Constituent Assembly, he said, “However good a constitution may be, it is sure to turn out to be bad because those who are called to work it happen to be a bad lot. However bad a constitution may be, it may turn out to be good if those who are called to work it happen to be a good lot.”

This was the onerous burden that Amebedkar and the framers of the Indian Constitution put on future governments and leaders. There was, however, no doubt in Ambedkar’s mind that along with time the Constitution would be amended. In his concluding speech, Ambedkar pointed out that compared to the American and Australian constitutions, the process for amendment of the Indian Constitution was much simpler. Indeed, the provisions for amendment is what makes a constitution a living document, and successive governments have not been shy of using it. So far the Indian Constitution has been amended 94 times; and there are plenty more on the way. This is in contrast to the US Constitution, ratified over two centuries ago, which has been amended a mere 27 times; the first 10 – or what is known as the Bill of Rights – happening within a few years of the Constitution coming into effect.

Article 31B and the Ninth Schedule

One of the more far-reaching components of the First Amendment was Article 31B, which created the Ninth Schedule into which legislation could be put and made immune from judicial review. Over time, over 280 Acts and Regulations have been put in the Ninth Schedule — a majority related to land reform but others on diverse areas ranging from mining to foreign exchange to monopolies — leading a commentator to label it a constitutional “dustbin”.

Forty-second Amendment

Since that first tweaking of the Constitution, amendments have flowed thick and fast. In subsequent years there have been several crucial amendments impacting creation of new states, electoral laws and federalism. But perhaps the one that has scarred, and scared, the nation the most was the infamous Forty-second Amendment rammed through during the Emergency.

The amendment building on two earlier ones – the Twenty-fourth and the Twenty-fifth – empowered Parliament to make laws infringing on the Fundamental Rights and put curbs on the courts over the custody of the Constitution.

The Forty-second Amendment had inserted two clauses in Article 368 specifying that amendments made under this article could not be challenged in court and that there would be no limitation on the power of Parliament to amend the Constitution. It also gave the Directive Principles of the Constitution primacy over Fundamental Rights. In keeping with this sentiment, the words ‘secular’ and ‘socialist’ were inserted in the Preamble of the Constitution.

When the Forty-second Amendment was introduced in Parliament, law minister H R Gokhale tried to sweeten it by saying, “If at all the powers [of Parliament] have been to a certain extent widened, they are not taken away in all matters in which really judicial action is justified.”

The future course of events would, however, show the resilience of Indian democracy. Once Indira Gandhi was voted out of power, the Janata government undid much of the harm done during the Emerging by bringing in the Forty-third and Forty-fourth amendments.

Ninety-third: 2006

The story of amendments and the turf battle between Parliament and the courts for custody of the Constitution is a continuing one. One of the more recent amendments – the Ninety-third in 2006 – which enforced reservation in unaided educational institutions came in the backdrop of a Supreme Court ruling putting a check on state regulation of admission procedures of private institutions.

The tension over who holds the key to the Constitution is going to remain so long as the power to amend is in the hands of Parliament and the courts have the authority of judicial review. This is true for older democracies such as the US too. Hence, political scientist Rajeev Bhargava points out, “We cannot treat the Constitution with sanctimonious reverence, too sacred to be touched, nor can we allow frivolous attempts to revise the Constitution every time a political deadlock occurs.”

The Emergency showed the danger of the government of the day subverting the Constitution and its principles. But its aftermath also showed that reckless tampering would not go unchallenged. That is what makes the Constitution a touchstone for Indian democracy, however mixed the quality of our politics and leadership might have been since 1950.

WEIGHTY ISSUE OF A DIFFERENT KIND: B R Ambedkar is snapped in a jovial mood with S K Bole during the reception at Mumbai’s Victoria Terminus Railway Station in 1951. Amid peels of laughter, the former law minister invited his old associate to sit on his lap when it was found that there were not enough chairs

How is the Constitution amended?

From the archives of The Times of India 2010

Is amending the Constitution common?

Globally, its not uncommon to amend or even rewrite constitutions. Our own Constitution specifically provides for a procedure to amend it. The preface says that the Constitution is a living document, an instrument which makes the government system work and that its flexibility lies in its amendments.

Can the Constitution be amended by a simple majority?

Yes. Depending on the gravity of the article and the outcome of the change, our Constitution provides for three methods of amendment. The first is by a simple majority in both Houses of Parliament, the second is by a special majority, and the third by a special majority in the Parliament along with a ratification by at least half of the state legislatures. Many articles in the Constitution mention that they can be amended by a law of Parliament, which means these articles can be amended by a simple majority just like an ordinary bill. For instance, Article 2 states that Parliament may by law admit into the Union, or establish, new states as it thinks fit. Sikkim was incorporated into the Union of India by the 36th Amendment Act, 1975. In most cases a motion, resolution or a bill requires support of a simple majority of the members who are present and participating in voting. However, for some other articles the amendment has to be done by a special majority as mentioned in Article 368.

What is a special majority?

Article 368 states that a bill has to be passed in both the Houses by a majority of the total membership of each House, and by a majority of not less than two-thirds of the members present and voting. In such cases, a Constitution amendment bill has to have a minimum support of at least 273 MPs in the LS, irrespective of the number of MPs present at the time of voting, apart from at least two-thirds of those present and voting. If the entire LS was voting, in such a case, the bill would need the support of a minimum of 364 MPs.

The bill must also be passed by both Houses in the same form, because any amendment to the bill itself also requires a special majority. There is no provision for a joint session in these cases, and hence, a party with a majority only in LS can not get the bill passed on its own. Like other bills, such a bill is then sent for the President’s assent, but unlike other bills, the President has no powers to send it back for reconsideration.

Which bills are sent to state legislatures?

When an amendment aims to modify an article related to distribution of powers between the Centre and the states, or to representation of states in House, or to changing the provision of Article 368, it is necessary for the amendment to be ratified by legislatures of at least half of all the states of India — 14 in present scenario. However, to prevent the amendment process becoming impractical, only a simple majority is required in state legislatures.

The most fundamentally transformative amendments

What are some of the most fundamentally transformative amendments that India’s Constitution has seen over the years? Rukmini S of The Hindu asked Alok Prasanna Kumar, Senior Fellow at the Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy for his opinion, and here are his Top 10.

1951: 1st Constitutional Amendment

Imposed restrictions on freedom of speech, allowed reservations in schools and government jobs, and prevented challenges to land reform laws by creating the 9th Schedule. Most of the amendments were introduced after High Courts had struck down laws of state legislatures restricting freedom of speech, providing reservations and introducing land reform.

1956: 7th Constitutional Amendment

Following the demand for linguistic states, this Amendment radically altered boundaries of the existing States on linguistic and ethnic lines following the report of the First States Reorganization Commission (the Fazl Ali Commission) and agitations which preceded that

1971: 26th Constitutional Amendment

Part of Patel’s mammoth task of unifying India’s princely kingdoms, large and small, was the promise of a “privy purse” in lieu of the enormous revenues that the princes enjoyed from their kingdoms. First abolished by ordinance, which was struck down by the Supreme Court and then abolished once again by Amendment.

1975: 39th Constitutional Amendment

The only amendment that has so far been passed with the sole intent of protecting one person: Indira Gandhi, whose election had been annulled by the Allahabad High Court. This was struck down by the Supreme Court while, ironically setting aside the Allahabad High Court judgment annulling her election.

1977: 42th Constitutional Amendment

Indira Gandhi’s Government virtually re-wrote large parts of the Constitution taking away judicial review, amending the preamble to add the words “socialist” and “secular”, cutting deep into judicial independence and significantly reducing Fundamental Rights protections among many other amendments. By far the most extensive amendment to the Constitution virtually creating a brand new Constitution.

1978: 44th Constitutional Amendment

The Amendment introduced by the Janata Government primarily to undo the ills of the 42nd Amendment Act, after a few changes were initially made by the the 43rd Amendment Act. It restored the independence of the judiciary, the enforceability of fundamental rights and judicial review, but crucially did not re-introduce the right to property as a fundamental right, preferring to protect it as a constitutional right.

1985: 52th Constitutional Amendment

To curb growing instances of horse trading and defections, the tenth schedule was introduced in the Constitution disqualifying MLAs/MPs who defected from their party either by loss of membership or through voting.

1989: 61st Constitutional Amendment

Reduced the voting age from 21 to 18 opening up the franchise to a large section of the population.

1992: 73rd & 74th Constitutional Amendments

Though ostensibly two separate amendments, they are often seen as part of one unified attempt to try and fulfil Gandhi’s dream of devolution of power to the lowest units of governance: the Panchayats.

2002: 86th Constitutional Amendment

Right to Education was first introduced as an enforceable Fundamental Right where earlier it had been a non-enforceable Directive Principle of State Policy.

Highest number of amendments

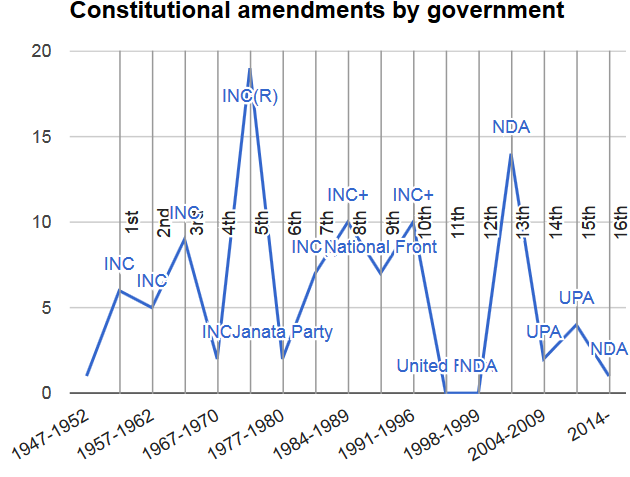

Indira Gandhi’s government from 1971 to 1977, which included the Emergency years, passed the most Constitutional amendments (19). The next highest number was under the Atal Bihari Vajpayee government (14).

Struck down by the Supreme Court

Only five constitutional amendments have ever been struck down by the Supreme Court, according to analysis by the Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy:

Kesavananda Bharati v State of Kerala (1973) which struck down part of the 25th Amendment for taking away judicial review of land reform laws;

Indira Gandhi v Raj Narain (1975) which struck down part of the 39th Amendment for taking away judicial review of elections of the PM and Speaker;

Minerva Mills v Union of India (1980) which struck down parts of the 42nd Amendment for making Directive Principles superior to Fundamental Rights and for removing judicial review over amendments to the Constitution;

P Sambamurthy v State of Andhra Pradesh (1987) which struck down part of the 32nd Amendment for permitting the Government of Andhra Pradesh to modify or change orders of Administrative Tribunals before it decides to implement them; and

L Chandra Kumar v Union of India (1994) which struck down part of the 42nd Amendment for taking away the power of the High Court to review judgments of tribunals.

See also

The Constitution of India (issues) <> The Constitution of India: Amendments<> The Constitution of India: Amendments 1-25<> The Constitution of India: Amendments 26-50<> The Constitution of India: Amendments 51-75<> The Constitution of India: Amendments 76-100

And also

A note on grammar and usage

Indpaedia has received the following advice:

The correct way to write it is ‘Article 239AA in the Constitution of India.’

‘of the’ is used to indicate a part of something, while "in" is used to indicate a location within something. The Constitution of India is a document, so we would use "in" to indicate that Article 239AA is located within the document.

Article 131 in the Constitution of India

Article 142 in the Constitution of India

Article 239AA in the Constitution of India