The Constitution of India (issues)

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

The Constitution of India

History

Before-1947

Baroda

Rahul Sagar, Sep 25, 2022: The Times of India

How many in contemporary India are aware that the earliest concerted push for constitutionalism occurred not in British India but in “Indian India”? The story goes like this. In the first half of the 19th century, the British had come to the conclusion that the native states were a morass where “despotic” rulers treated their subjects as “mere milch cows”.

Since meddling openly generated resentment, the British tried to use education to produce “responsible” rulers. Baroda became a test case for this approach. After Malhar Rao was deposed on grounds of maladministration in 1875, the British selected Sayaji Rao Gaekwad, then an illiterate 12-year-old, and set about grooming him for office. Under the supervision of his Oxford-educated tutor, Frederick Elliot, Sayaji Rao was introduced to various “gentlemanly” activities. But then on the eve of his ascension, a fierce debate broke out over the rightful role of a maharaja.

The traditional view in the native states was that a maharaja was entitled to decidedly absolute rule in the interest of his dynasty. This view now came under attack from ambitious and patriotic young men in Bombay Presidency, who had received a modern education. Hoping to see the backs of the British, they urged Sayaji Rao to “strengthen his state”. Remarkably, Elliot nurtured these views. Because he wanted to make Sayaji Rao, whom he cherished, a leading figure in western India, he let his ward mingle with Maratha firebrands. Thus, it was that Sayaji Rao came into possession of Niccolò Machiavelli’s ‘Prince’, which he promptly “adopted as his political guide”.

This development shocked the British who set about trying to oust Elliot. It also alarmed Baroda’s celebrated Dewan, Sir Madhava Rao. It was all very well to be moved by Machiavelli’s exhortation to liberate one’s patria (homeland) from “barbarians”, but much depended on knowing how to do this. Having devoted his career to preserving native states from the grasping British, Rao was only tooaware of their comparative weakness. And so, in 1881 the anxious Dewan convinced the British to allow him to deliver to Sayaji Rao a “special education” in the form of lectures on the “art and science of government”.

In his lectures, Rao urged Sayaji to see that the circumstances he confronted were quite unlike those in Machiavelli’s Prince. What maintained the British in India was public credit and public opinion: Indians were willing to lend them money and obey their laws because they expected them to improve their lives — and did not foresee a better alternative. Consequently, violence could accomplish little, as the great mass were unlikely to side with the native states. To supplant the British, the native states would need to outperform them. And in an age where newspapers were watching the ruler’s every move, half-measures would fool few. “A fierce light beats upon the throne,” Rao warned. Only thoroughgoing reform would suffice: the native states had to establish a constitutional order in which governance would depend not on the maharaja’s penchants but on impartial and capable public institutions.

Rao struggled to be heard. The constitution he proposed to Gaekwad was denounced by traditionalists and militants alike. The sardars and bais mocked him as a “Madrasi” who wanted to turn Baroda into Britain, while hotheads in Bombay, reportedly including the young Bal Gangadhar Tilak, circulated anonymous pamphlets accusing him of timidness. But the story does not end there. Rao’s entreaties prompted a much wider debate in western India. It led to dozens of publications on the importance of constitutionalism, which decisively shaped the world view of liberals clustered in the Poona Sarvajanik Sabha and the Indian National Social Conference, most notably M G Ranade and G K Gokhale. These figures then went on to shape the “moderate” wing of the Indian National Congress, which made constitutional reform its signature.

This is only one example of how the native states contributed to ideas and policies that have shaped contemporary India. There are many other stories to be told: about Mysore and Travancore fostering representation, Tanjore and Vizianagaram revitalising culture, Bhavnagar and Gondal encouraging education, Indore and Mayurbhanj facilitating enterprise, and Kapurthala and Bikaner advancing diplomacy. As we continue to excavate these stories, we will see that the natives states were patrons of wider national progress, serving as incubators of talent, arenas of debate, and laboratories of policy. And perhaps then we will give them their due by celebrating their contribution to the making of modern India. ¦ Rahul Sagar teaches political science at NYU Abu Dhabi and is the author of ‘The Progressive Maharaja: Sir Madhava Rao’s Hints on the Art and Science of Government’

The Constitution’s journey: 1946-2022

January 26, 2022: The Times of India

India’s independence was celebrated crowds. In contrast, the nation’s metamorphosis into a republic was a much more sober affair. Compared to August 15, 1947, the front page headline of this newspaper on January 28, 1950, (no paper was published on January 27) was staid, proclaiming — ‘India Becomes Sovereign Democratic Republic’ — with a picture of India’s first president Rajendra Prasad being sworn in. This news jostled with other items like a “Communist-sponsored” demonstration against Republic Day in Calcutta, a bomb thrown at the Nizam of Hyderabad and the US signing a pact with western European powers.

Before the nation was officially declared a republic on January 26, 1950, several acts went into it. The most notable was the Constituent Assembly, meeting between 1946 and 1949 and framing the Constitution, which forms the republic’s nucleus. It was adopted on November 26, 1949. Indeed, while Independence Day was about the exhilaration of freedom from British rule, Republic Day was really about the adoption of the Constitution, crafted by Indians, to henceforth act as a lodestar to the nation.

Among the most important things the new republic did was to mandate universal adult suffrage, critical since the word republic draws from the Latin phrase ‘res publica’, where a state draws legitimacy from the public or the people. In fact, the Constituent Assembly itself was elected on the basis of a limited electorate. Adult suffrage was a revolutionary step given the widespread poverty and illiteracy in India. Some members expressed unease with adult suffrage, one calling it a “grand leap in the dark”. Outside the Assembly, even Rajendra Prasad had reportedly voiced his “grave anxieties” at a public meeting about adult franchise.

However, Alladi Krishnaswamy Aiyar, the lawyer whom Ambedkar called more “competent” than him, made the most eloquent defence of the principle in the assembly saying the “introduction of democratic government on the basis of adult suffrage will bring enlightenment and promote the well-being, the standard of life… and… decent living of the common man. ” It is no accident the preamble to the Constitution begins, “We the people…” The Constitution, albeit with frequent and often substantial amendments, alongwith elections, has been

the cornerstone of the Indian republic. The first amendment to it – when the provisional Parliament was in place and the first election of free India was yet to be held – was farmany subsequent amendments, the first amendment was partly dictated by the government’s ideological concerns and partly to strengthen the state. The court rulings.

At the time, an exasperated Jawaharlal Nehru had proclaimed in Parliament, “Somehow we have found this magnificent Constitution we have framed, was later kidnapped and purloined by lawyers. ” Among other things, the first amendment curtailed freedom of speech, introduced caste-based reservations and set in place land reforms by restricting the right to property.

Similar forces were at play during the early years of Indira Gandhi’s term as prime minister when many of her policies, including bank na- tionalisation and abolition of the privy purses, ran afoul of the Supreme Court, culminating in the landmark Kesavananda Bharati ruling in 1973. In one of the most famous judgments in India’s constitutional history, a 13-judge bench, the largest ever in Supreme Court, in eleven separate opinions structure” doctrine, which essentialmandate to “alter the basic structure or framework of the Constitution”. events, including nationwide protests 1975 Allahabad high court ruling finda state of emergency in 1975. Most into bend, but you crawled. ” After having imposed the Emergency, the Indira government struck back at the judiciary with the 42nd amendment, which said certain amendments could not be challenged in court and that there would be no limitation on Parliament’s power to amend the Constitution.

It was left to the people, the voters, to chastise Indira, handing her a resounding defeat when she called elections in 1977. One of the achievements of the Janata government, which lasted 28 months and was marred by factional rivalries and leadership struggles, was the restoration of the republic and parliamentary democracy.

Nearly four decades later, as majoritarian tendencies gather momentum around the world, it is imperative for citizens everywhere, including India, to preserve and protect the fundamental rights and civil liberties that were won with so much struggle and sacrifice by preceding generations. What Ambedkar had cautioned in his final speech in the Constituent Assembly on November 25, 1949, still holds true: “However good a Constitution may be, it is sure to turn out bad because those who are called to work it, happen to be a bad lot. However bad a Constitution may be, it may turn out to be good if those who are called to work it, happen to be a good lot. ”

Its resilience

D Shyam Babu, January 26, 2022: The Times of India

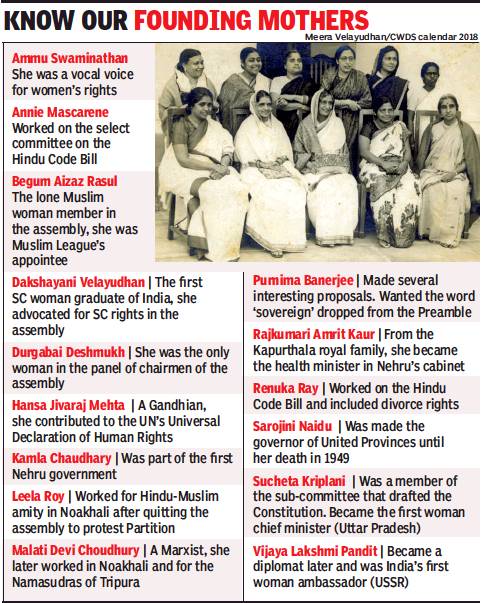

Highlighting how resilient the Constitution of India had been during the first half-century of its existence, eminent jurist Fali Nariman narrated in 2002 how Sir IvorJennings – that ‘prolific author of Westminster-type constitutions’ – was dismissive of our law of the land. Invited by theUniversity of Madras to lecture on the Constitution when the document was barely a year old, he said it was “too long, too detailed, too rigid”. Indeed!The same Sir Ivor had helped draft constitutions for SriLanka (then Ceylon)and Nepal but neither outlived its infancy. Such is the fate of most constitutions in the developing world. It mattered not whether a constitution was homegrown or borrowed, too long or two short, it proved to be toofrail to live longer. But the IndianConstitution stands as a beacon of stability and longevity. However, one can readily concede to its shortcomings: it’s too long, too alien, etc. And one can as wellthrow in yet another charge:it’s too elitist. What then explains the success of a document that is plagued by somany infirmities?An often neglected factorfor the Constitution’s successis its popularity, the realisation among an overwhelming majority of Indians that itreflects and guarantees theirbasic human rights. Aboveall, the document symbolisesthe nation-inmaking. It is nomere past perfect,but a charter ofpresent continuous. For the downtrodden – lowercastes, especiallyDalits and tribals,and women – itsymbolises notonly a break from centuries of oppression andsubordination but the hopefor a bright future. A case in point is the adnauseam debate on the everexpanding ambit of quotas. While one may be right in finding fault with the logic of quotas, one must recognise thatany debate thereon is invariably anchored to constitutional guarantees. The legitimacyand longevity of any constitution depend on the peoples’faith that it has direct andpositive bearing on their lives. What gives the documentits heft is its structure in thatit is comparable to most constitutions in the developedworld, as well as its pedigree,above all epitomised by itschief architect, Dr Ambedkar. However, its depth comes fromthe 299-member Constituent Assembly which was broadlyrepresentative of the country. Each of the 15 women members in the Assembly, for example, was there in her own right. Some of them, such as Durgabai Deshmukhand RajkumariAmrit Kaur, wenton to make enduring contributionsto the nation. Twoother members,Hansa Jivraj Mehta and Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit, madetheir mark at theglobal level. the Assembly rendered gender justice a fait accompli, no matConstitution was adopted, her Declaration of Human Rights be absolute and unambiguous.

Being one of the two female members of the UN Commis- sion that drafted the Declaration, Mehta insisted that in article 1, the expression “All men are created equal. . . ” be replaced by “All human beings are created equal. ” She reasoned that ‘men’ might be representative of all human beings but there could be occasions when women might be excluded. Eleanor Roosevelt, the other female member of the Commission, became its chairman and it was Mehta who proposed Roosevelt’s name.

Though Mehta’s demand that there ought to be some mechanism to ensure human rights are enforced was rejected, the challenge of compli- ance still haunts the world.

As with the freedom struggle, so is the case with constitution-making, we have ended up men and women whose contributions and sacrifices are second to none. For example, in his ‘rebels’ for praise – such as H V made it to the Constitution. But they were large-hearted enough to add their seal of approval to the doculone member refusing to add his signature to the Constituganged up and withdented the Constitution’s legitimacy. It is heartening that the younger generation is embracing the Constitution as a progressive and inclusive instrument deserving our reverence. Its remembrance and celebration constitute our secular creed and practice. The Republic Day Walk being organised in Chennai for promoting conversations around equity is a praiseworthy initiative.

People claiming the Constitution their own will be the ultimate safeguard against corrosion from within and sabotage from without.

November 26, 1949: the Constituent Assembly adopts the Constitution

Yashee, Nov 27, 2025: The Indian Express

Constitution Day of India 2025: On November 26, 1949, the Constituent Assembly adopted the Constitution of India, which came into effect on January 26, 1950. While January 26 is celebrated as Republic Day, since 2015, November 26 is observed as the Constitution Day of India, or Samvidhan Divas.

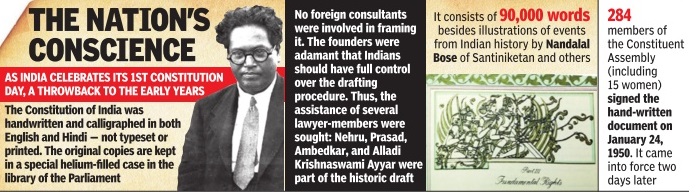

The Constituent Assembly took two years, 11 months and 17 days to draft the Constitution for Independent India. During this period, it held 11 sessions covering 165 days, and its members submitted around 7,600 amendments to the draft Constitution.

November 26, 1949, thus, was the culmination of a momentous journey. When the Constituent Assembly met that day, two resolutions were adapted — “That the Constitution as settled by the Assembly be passed”; and “that the Constituent Assembly do adjourn till such date before the 26th of January, 1950 as the President may.”

Before this, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel made a short statement, announcing that states had accepted the Constitution the House had gathered to adopt.

President Rajendra Prasad then made a speech congratulating the members for their achievement, with special mention of a few, including Ambedkar, Patel, and Jawaharlal Nehru. Here are the highlights of his speech, and of the day.

On the Constitution’s language

When the Assembly met that day, United Provinces (later Uttar Pradesh) member Algu Rai Shashtri asked the President, “I would like to know from you as to when and in which form the Hindi Translation of this Constitution would appear… you had yourself declared that the Constitution of our Nation would be framed in our own National Language but you have not yet made any definite announcement on this question.”

To this, Rajendra Prasad replied, “You would be aware that some articles have been adopted in the Constitution wherein it has been decided which would be the language for official use. Therein it has also been decided that for the next 15 years all official work at the Centre would be carried in English… At present perhaps it will not be possible to place the Constitution in Hindi before this House and to get it adopted. Besides this, the Constituent Assembly has itself passed a resolution directing me to publish the Hindi translation of the Constitution by the 26th of January. I am making arrangements for that and the translation would be published by the 26th of January…I would also, as soon as possible, get it translated and published in other languages.”

The monetary cost of preparing India’s Constitution

Prasad also mentioned how much money the process of preparing the Constitution had cost. “The cost too which the Assembly has had to incur during its three year’s existence is not too high when you take into consideration the factors going to constitute it. I understand that the expenses up to the 22nd of November come to Rs. 63,96,729.”

The two ‘intractable problems’ solved

Prasad talked about how the British had conquered different parts of India at different times, and when they left, integration of the various territories had been a major problem. “The Constituent Assembly therefore had at the very beginning of its labours, to enter into negotiations with them to bring their representatives into the Assembly…It must be said to the credit of the Princes and the people of the States no less than to the credit of the States Ministry under the wise and far-sighted guidance of Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel that by the time we have been able to pass this Constitution, the States are now more or less in the same position as the Provinces.”

The other major issue he mentioned was “the communal problem”, and celebrated the end of separate electorates. “…even reservation of seats has been given up by the communities concerned and so our Constitution does not provide for reservation of seats on communal basis, but for reservation only in favour of two classes of people in our population, namely, the depressed classes who are Hindus and the tribal people, on account of their backwardness in education and in other respects,” Prasad said.

His two regrets

“There are only two regrets which I must share with the honourable Members,” Prasad said.

“I would have liked to have some qualifications laid down for members of the Legislatures. It is anomalous that we should insist upon high qualifications for those who administer or help in administering the law but none for those who made it except that they are elected.”

“The other regret is that we have not been able to draw up our first Constitution of a free Bharat in an Indian language. The difficulties in both cases were practical and proved insurmountable. But that does not make the regret any the less poignant.”

Dr Rajendra Prasad On the making of the constitution

January 26, 2026: The Times of India

From: January 26, 2026: The Times of India

On March 15, 1946, Mr. Attlee, the British Prime Minister, made an announcement that a Cabinet Mission consisting of Lord Pethick-Lawrence, Sir Stafford Cripps and Mr. Alexander, would be “going to India with the intention of using their utmost endeavours to help her to attain her freedom as speedily and fully as possible. What form of Government is to replace the present regime, is for India to decide.

The Cabinet Mission arrived in India shortly afterwards and together with the Viceroy, Lord Wavell, carried on discussions and negotiations with leaders of political parties in India among whom the chief were the Indian National Congress and the AllIndia Muslim League. They also interviewed representatives of the Princes of India. Finding that no agreed solution was possible, they issued a statement on May 16, 1946, wherein after referring to certain proposals which they considered impracticable, they made their suggestions which they thought represented the maximum agreement that was possible.

STATES

With regard to States, they said: “It is quite clear that with the attainment of Independence by British India… the relationship which has hitherto existed between the Rulers of the States and the British Crown will no longer be possible…”. They felt assured, however, that the States were ready and willing to co-operate in the new development of India. The precise form which this co-operation would take was to be a matter for negotiations. They suggested that a constitution making machinery should be brought into being forthwith to enable a new constitution to be worked out. The Constituent Assembly met for the first time on the 9th of December 1946, but without those Muslim representatives who had been elected on the ticket ot the All-India Muslim League. It proceeded to carry on negotiations with the Princes…. The States gradually sent their representatives and by the time the Constituent Assembly finished its labours, all the States within the geographical limits of India with the exception of Hyderabad were represented by their own representatives on the Constituent Assembly.

After formulating its own rules of procedure, the Constituent Assembly settled its own terms of reference in the shape of an objectives resolution which declared its intention to constitute India into a sovereign republic and to draw up a constitution which would constitute what were then the British Provinces and the Indian states as well as other territories willing to join India into a Union, would guarantee, justice, social, economic and political, equality of status, of opportunity and before the law, freedom of thought, expression, belief, faith and worship, and would provide adequate safeguards for minorities, backward and tribal areas, depressed and other backward classes.

By the time the transfer of power took place on August 15, 1947, all the Indian States in geographical contiguity with India except Kashmir and Hyderabad had acceded to India on three subjects, namely Foreign Affairs, Defence and Communications.

While the Constitution was in the process of being drafted, a movement for the integration of the States started. In the first place the smaller States chose to become integrated with the Province of the Indian Provinces contiguous to them and otherwise having affinity with them.

COMPLEX ISSUES

The Constituent Assembly has taken nearly three years to complete this work. It has had eleven sessions and sat in all for 165 days and the cost incurred on its account up to November 22, 1949, comes to Rs. 63,96,729. Considering the complexity of problems and the development of events that have taken place during this period, the time taken has not been too great. The Constitution comprises some 395 Articles and 8 Schedules. The bulk is undoubtedly great, but not too great when we consider the variety of subjects with which it has had to deal.

(Read the full version of this article on timesofindia.com)

The drafting of the Constitution of India

The process

The Times of India, Nov 27 2015

How we codified what India stands for WHEN DID THE PROCESS OF DRAFTING INDIA'S CONSTITUTION BEGIN?

In 1934 Indian leaders demanded a constituent assembly to draft a Constitution reflecting the ideals of an independent India, the process began more than a decade later. The constituent assembly first met on December 9, 1946 in the Central Hall of Parliament, then called Constitution Hall; more than 200 representatives attended, including nine women. Sachchidananda Sinha was elected temporary chairman, to be soon replaced by Rajendra Prasad.

How was the assembly constituted?

Constituent Assembly members were chosen mainly through indirect election by provincial assemblies, as per Cabinet Mission recommendations. 292 members were elected through provincial assemblies, 93 represented princely states and four represented chief commissioners' provinces, including the Northwest Frontier Province, Balochistan, Coorg, Ajmer-Merwara, Andaman and Nicobar. Total membership: 389.

How did it function?

On December 13, 1946, Nehru moved the `Objectives Resolution' stating the assembly's declaration proclaiming India an independent sovereign republic. It resolved to draw the operational characteristics of government in independent India. Soon after Mountbatten's partition plan was declared on June 3, 1947, a separate constituent assembly was set up for Pakistan, reducing the Indian body's members to 299. Before Independence, legislation was through the Central Legislative Assembly . On August 14, 1947 midnight, this was replaced by the constituent assembly. It had 17 committees to discuss all aspects of the new democracy .

How often has the Constitution been amended?

The Constitution has been amended 100 times, making it the world's mostamended statute. The first amendment came in 1951, a year after the Constitution came into effect. The last one became effective this May to make it possible for the India-Bangladesh land boundary agreement to be implemented. The Constitution framers felt the process of amending it should be neither too easy , which would defeat the very purpose of having a Constitution, nor too difficult, which would make it impossible for the document to keep up with changing social values. For amending the Constitution, a Bill can be intro duced in either House, but must win support of a majority of the total membership of each House (including vacancies, if any) and two-thirds of those present and voting (including “ayes“ and “nays“, excluding those abstaining) in each House.

If the Bill fails to pass this test in one House, no joint sitting of Houses can be used to get it passed. Where the proposed amendment imping es on the power of the states, it must be ratified by at least half the state legislatures. Which are the important amendments?

Some amendments have been significant. The first amendment in 1951 introduced Schedule 9 to protect laws that are on the face of it contrary to constitutionally guaranteed fundamental rights from judicial review.For example, a law allowing the state to forcibly acquire land for public good would seem to violate the right to property, but placing it in Schedule 9 (as the 17th amendment of 1964 did) was to put it beyond the reach of the courts. In 2007, the SC ruled that even laws under Schedule 9 are open to judicial review, if they violate the basic structure of the Constitution.

The Seventh Amendment of 1956 was to enable creation of linguistic states and of UTs while abolishing the earlier classification of Class A, B, C and D states.The 39th and 42nd amendments passed during Emergency in the mid-70s were controversial. The 39th placed restrictions on judicial scrutiny of the PM and the 42nd curtailed fundamental rights while introducing the concept of fundamental duties. It added the words secular and socialist to the preamble that defines the republic's nature.

The 43rd and 44th amendments passed after Emergency reversed some of the excesses. Rajiv Gandhi's tenure saw some crucial changes. The 52nd amendment of 1985 was to introduce an anti-defection bill while the 61st in 1989 reduced voting age to 18 from 21. The 73rd and 74th amendments allowed creation of a third tier of government through local bodies in rural and urban areas. The 86th amendment of 2002 conferred the right to education.

How long did it take to draft the Constitution?

It took two years, 11 months and 17 days to compile the world's longest national statute. The constituent assembly held 11 sessions over 165 days. On August 29, 1947, it set up a drafting committee under Ambedkar.The constitution was adopted on November 26, 1949. It came into force on January 26, 1950. That day the assembly became the provisional Parliament of India. This date was chosen to honour the “purna swaraj“ declaration of 1930.

The spirit

A union of states

Chandrima Banerjee, February 8, 2022: The Times of India

It is the first line in the Constitution, right after the Preamble — “India, that is Bharat, shall be a Union of States.” But when Congress MP Rahul Gandhi referred to it while speaking in the Lok Sabha on February 2, considerable uproar followed.

“If you read the Constitution of India, you will find — and many of my colleagues who have not read it should look at it — that India is described as a ‘Union of States’. India is not described as a nation, it is described as a ‘Union of States’,” he had said. “Meaning it is a negotiation, a conversation … It is a partnership, it is not a kingdom.”

BJP’s IT cell head Amit Malviya called it “deeply problematic and dangerous.” And BJP MP Nishikant Dubey moved a privilege notice against Gandhi in the Lok Sabha, saying he wanted to “incite” people with his statements which were in “contempt of the House”.

Like each phrase, punctuation (and even order of words) that eventually found its way into the Indian Constitution, “Union of States”, too, was debated for all its possible implications by the makers of the country’s legal code after Independence. And they had made a conscious choice to leave it in.

Every word was deliberated on

In 1948, a committee prepared a draft version of the Constitution and sent it out to all members. Over the next eight months, they sent in suggestions or proposed amendments. The public, public bodies and provincial governments were also asked to chip in.

Based on these inputs, the Drafting Committee reworked many articles.

This revised Draft Constitution was placed in the constituent assembly. Each article was then taken up, one by one, for debate over every possible nuance. If someone wanted an amendment to an article being debated at the time, they could “give notice” and then that would be discussed and put to vote.

So, why ‘union of states’? When BR Ambedkar tabled the Draft Constitution on November 4, 1948, he made it clear that it was a “Federal Constitution” — “this dual polity under the proposed Constitution will consist of the Union at the Centre and the states at the periphery.”

And that the Indian Constitution would not be for a “league of states nor are the states administrative units or agencies of the Union government.”

The debate that followed then was similar to the one now. Ambedkar said, “Some critics have taken objection to the description of India in Article 1 of the Draft Constitution as a Union of States. It is said that the correct phraseology should be a federation of states.”

He cited two examples: South Africa was a unitary state (governed by a central government) and Canada was a federation (group of partially self-governing states), but both called themselves “unions”.

“Thus the description of India as a Union, though its Constitution is federal, does no violence to usage. But what is important is that the use of the word Union is deliberate,” he added.

Then, he went on to explain why the phrase was chosen.

“I can tell you why the Drafting Committee has used it. The Drafting Committee wanted to make it clear that though India was to be a federation, the federation was not the result of an agreement by the states to join in a federation and that the federation not being the result of an agreement no state has the right to secede from it.” In simple words, India was not a country that states “joined” (though the princely states did exactly that but that’s a separate debate) but a larger unit they were part of already.

“The federation is a Union because it is indestructible,” Ambedkar continued. “Though the country and the people may be divided into different states for convenience of administration the country is one integral whole, its people a single people living under a single imperium derived from a single source … The Drafting Committee thought that it was better to make it clear at the outset rather than to leave it to speculation or to dispute.” So, the phrase “Union of States” was meant to uphold territorial integrity, not incite secession.

‘Too much’ autonomy or ‘too little’?

The following day, on November 5, the debate came up again — how much power should the Centre have? Damodar Swarup Seth, the socialist freedom fighter from UP, said, “Our Indian Republic should have been a Union — a Union of small autonomous republics.”

Why did Seth say so? “Had there been such autonomous republics, neither the question of linguistic provinces nor of communal majorities or minorities or of backward classes would have arisen … The natural consequence of centralising power by law will be that our country which has all along opposed fascism — even today we claim to strongly oppose it — will gradually move towards fascism.”

Not everyone agreed.

Bengal politician Lakshmi Kanta Maitra said that retaining the phrase could lay the ground for secession later because many states had indeed “acceded to the Indian Union”, a voluntary act. “If this description of India, as is given in Articles 1 and 2, is retained, these states may contend, at some later stage, that they were sovereign states and were united to the Indian Union by purely voluntary arrangement,” he added. “We want to make it perfectly clear in the Constitution that this Union is an indissoluble Union of indestructible states, states in the sense of constituent units.”

The constituent assembly went back to the question about a year on.

On September 17, 1949, Urdu poet and freedom fighter from UP Hasrat Mohani objected to the phrase. “I am opposed to this union of states. I do not want a Union of that kind. Because, originally we had republics. We have given up that idea of republics and we have brought in the states. This is a very serious matter. It cannot be disposed of in a simple manner.” But the amendment could not be debated. Prime Minister Narendra Modi said in Lok Sabha, "The House has been insulted by saying that word 'nation' is not in the Constitution"

The following day, on September 18, Mohani was given time to explain. Unlike other opponents of the phrase, who thought it created space for secession, he thought it did not give states enough autonomy.

“I say that I have got a right to propose that instead of 'union of states' it should be 'Union of Republics of India or Union of Socialist Republic of India',” he said. “The word republic is taboo for some people. If they do not have the courage to use it, and find difficulty in accepting that word, I have an alternative proposal to call them sovereign states of India. That is to say the provinces will be autonomous.”

Supporting the idea but for an entirely different reason, BM Gupta from Bombay said, “The states might consider that they are independent and their estimate of their status might be higher than what it really is. I therefore submit that at least as far as the right of secession is concerned, it is not too late yet expressly to negative it, if it is found necessary.”

Eventually, four proposals came up.

“India shall be a Union of Indian Socialist republics to be called UISR on the lines of USSR.” It was rejected.

“India or Bharat shall be a Union of Sovereign States of India or Bharat to be called USSI or USSB on the lines of USSR.” Also dismissed.

“Bharat, or, in the English language, India, shall be a Union of States.” Rejected again.

Finally, the constituent assembly settled on what is now Article 1 of the Constitution: “India, that is Bharat, shall be a Union of States.”

Uniquely Indian features

Examining the Constitution as it tookits final shape in November 1949, Constituent Assembly member Kengal Hanumanthaiah dejectedly remarked: ‘Wewanted the music of a veena or sitar, buthere we have the music of an English band. ’ It was afeeling that many shared, and the idea that the Constitution — and the institutional systems it engenders —lacks indigeneity and replicates anglicised forms ill-suited to Indian terrain has since been firmly ensconced inthe mainstream political discourse. Calls to ‘decolonise’India’s political and constitutional systems, one maderecently by Justice Abdul Naseer, abound. Some evenseek to lay the blame at Nehru’s door. It is true that indigenous, particularly Gandhian, alternatives put forward by men like Radhakamal Mukherjee and Shriman Narayan Agarwal were rejected out of hand. Yet the creation of the Constitution was far more than just thetransplanting of the Westminster system on Indian soil. Desperately poor, largely uneducated, with little real knowledge orexperience of parliamentarydemocracy, deep-seated socialdivisions and an absence of enabling background conditions, the India of 1947 — its political and judicial institutions —lacked the traditions, precedents,and conventions on which theirWestminster counterparts rested. It was the need to address this lack, whether through written constitutional text or through their own actions that created ‘instant conventions’, that gave India’s founding fathers the space to shape their own version of Westminster. The resulting conceptual and practical distinctions fromWestminster, and the white settler dominions of Australia,New Zealand, and Canada, were substantial. Even whileembracing Westminster-style democracy in form, India’sConstitution bent, twisted, and adapted its norms and techniques, creating something very different in substance:both unusual and hard to categorise. While many of thesedistinctions were indeed down to the impress of Nehru, itis important to note that these ideas were widely shared inthe Constituent Assembly, including by Ambedkar andPatel. Even when expressed in the language and paradigmof a British constitutional legacy, India’s Constitution created an institutional structure and political culture thatconstitutes a typology of its own, distinct from Westminster. It was, to quote the constitutional historian Harshan Kumarasingham, an ‘Eastminster’ — the first of its kind. In contrast to the uncodified or sparsely codified constitutions of the UK and the dominions, India’s Constitution,the lengthiest in the world by a mile, went into exquisite and extensive detail. This was driven not by a crude obsession with verbosity, but the need to explicate rules andprovide firm and detailed guidance for institutions. It was an indigenous answer to India’s circumstances: the absenceof experience, tradition and precedent emblematic of Westminster. Or as the political theorist Madhav Khosla recently reminded us in his book India’s Founding Moment, anattempt to use the Constitution as a pedagogical tool to trainIndian institutions and those who staffed them. It created a state explicitly committed to revolutionarysocial aims embedded in its Constitution, with individualrights hemmed in with multiple provisos that enabled thestate to override them and legislate its social revolutioninto being. Here again, the impress of Nehru and his socialist policies — then enjoying widespread acceptance asan answer to India’s poverty and social inequality — is clear. Through Article 123 that confers the power to promulgate ordinances, the Constitution clothed the executivewith legislative power and allowed the government tolegislate in place of Parliament, without declaring anemergency. This is a power unheard of in Westminster. Thisenshrining of executive supremacy placed the government in thedriving seat with the ability andthe power to set the agenda for alllegislative business. To stress thisdominance further, it prescribedno period for the duration of parliamentary sessions, leaving italmost entirely to the government to decide when the legislature is summoned and how longit sits. Unlike the House of Commons which can only be prorogued to a definite date, andwhere the average length of prorogation in the recent past hasbeen 18 days, the Lok Sabha is almost entirely at the executive’s mercy. Such executive pre-eminence, needed forNehru’s social revolution, was also widely accepted as asuitable answer to the exigencies of India’s condition. These are only some of the more obvious distinctions. There are many others. All of them are indigenous mechanisms, consequences of the framers’ attempts to groundthe Constitution in Indian conditions. As innocuous as theymay seem, they have engendered an institutional form andpolitical culture that is recognisably Indian, widely divergent from anything seen in Westminster — enough to barely be recognisable beyond the outward form. Even a cursory observer will notice Indian democracy is far from Westminster in substance, and its constitutional structures farfrom simply an anglicised transplant. Its divergences, whileshunning ‘Indian type institutions’ as Fali Nariman callsthem, for better or (in my opinion mostly) for worse, represent a kind of indigeneity that has served to root the Constitution in Indian soil. This Constitution is thus more thanan imposition or a transplant; it is the framing of its ownhybrid system: the ‘Eastminster’ system.

Singh is the co-author of ‘Nehru:The debates that defined India’

The 15 women who wrote the Constitution

March 6, 2024: The Indian Express

The women who wrote the Constitution of India

Among the 299-member Constituent Assembly, there were 15 women who advocated passionately for a kind of India that would bear the imprint of both genders. They argued ardently over a range of topics from reservations to the Uniform Civil Code.

These experiences informed their discussions, arguments and positions on subjects like reservations, minority rights and legislative finances. During the debate around the Hindu Code Bill, members like Durgabai Deshmukh and Hansa Kumari made strong arguments for a Uniform Civil Code, which they believed would ensure more equality for women.

Dakshayani Velayudhan and Begum Aziaz Rasul argued against reservations and separate electorates for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes. They believed that reservations would maintain an unbridgeable gap between minorities and the majority.

These women advocated for a kind of India that would bear that imprint of both men and women. Economic, social and political equality for everyone in society was their foremost goal. Despite being on the receiving end of distasteful comments from several Constituency Assembly members, these women spoke their minds and played a crucial role in scripting the sovereign and secular republic of India.

Annie Mascarene

Born in 1902, Annie Mascarene’s work as a lawyer and politician in Travancore influenced her arguments in the Constituent Assembly Debates greatly. She fought to integrate the princely state of Travancore into the newly independent India and became the first woman to hold a ministerial and legislative assembly position in Travancore.

Mascarene in the Constituent Assembly Debates firmly believed in the centralisation of power for a smooth functioning of a democracy. She also warned against complete centralisation which would negatively affect the nature of democratic institutions. She said that the task of the Assembly was to lay down the rudimentary principles of democracy for generations to come and not just for the near future.

Hansa Jivraj Mehta

As a staunch freedom fighter, women’s rights activist and member of the Constituent Assembly, Hansa Jivraj Mehta essayed several roles. On August 15, 1947 as the country celebrated its Independence and President Rajendra Prasad took the pledge of freedom, Mehta presented the country’s first national flag on behalf of the women of India.

Mehta remained committed to women’s issues throughout her life and, in the Constituent Assembly, made strong arguments against reservations for women. “What we have asked for is social justice, economic justice and political justice, not reserved seats for quotas and separate electorates,” she said. Mehta also served on the board of UNESCO and became the first Vice Chancellor of MS University in Baroda.

Dakshayani Velayudhan

Born into the Pulaya community of Kerala, Dakshayani Velayudhan faced acute discrimination from the upper caste communities in Cochin and Travancore. Movements against caste discrimination were becoming prominent.

Velayudhan affirmed that the Constituent Assembly does not just “provide a new framework for the country but also grants the people a new framework of life”. She was a Gandhian and opposed untouchability. She supported Article 17 of the Constitution which abolishes untouchability. Velayudhan did not pursue electoral politics but was actively involved in social work in Delhi.

Amrit Kaur

A princess by birth but a fierce activist by passion, Amrit Kaur played an important role both during the freedom struggle and in shaping independent India. Kaur joined Gandhi in the Civil Disobedience movement in 1930 and was passionate about the political participation of women.

Like many of her contemporaries, Kaur advocated for universal adult franchise and did not believe in reservations for women. Kaur believed that true equality would only be gained when women made it to the legislature through ordinary elections rather than through reservations.

More about Rajkumari Amrit Kaur | The princess who built AIIMS She advocated for the Uniform Civil Code along with Hansa Mehta and wanted to replace “free practice of religion” with “freedom of religious worship” in the draft Constitution. A secular at heart, Kaur carried with her a spinning wheel, the Bhagwad Gita and the Bible when she was jailed after the Quit India Movement.

Kaur also served as the first women Health Minister and founded renowned institutions like the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS).

Ammu Swaminathan

Fearless and politically charged, Ammu Swaminathan was a social worker, politician and anti-caste activist. Despite being born into an upper caste family, Swaminathan actively fought to erase caste-based discrimination in India.

Swaminathan started becoming politically involved in 1917 when she formed the Women’s India Association along with Annie Besant to address the social and economic problems of women workers. In the Constituent Assembly, Swaminathan supported the adult franchise and the removal of untouchability.

Having been at the receiving end of the practice of child marriage herself, she advocated for the Child Marriage Restraint Act and Age of Consent Act and the various Hindu Code Bills that pushed for reform in Hindu religious laws.

Durgabai Deshmukh

Remembered as the ‘Mother of Social Work’, Durgabai Deshmukh was one of the drivers of rigorous nation-building and social reform. Born in 1909 in Andhra Pradesh, Deshmukh did not come from a family of privilege. Since her childhood, she noticed cruel customs and poor treatment of women. When she was jailed during the Salt Satyagraha, Deshmukh observed that several women were imprisoned for crimes they did not even commit.

After this, Deshmukh decided to become a lawyer and pioneered the Andhra Mahila Sabha in 1937, which became an institution of education and social welfare. In the Constituent Assembly, she weighed in on judicial matters and advocated lowering the age from 35 to 30 to hold a seat in the Council of Ministers.

After Independence, she also served in the Planning Commission as a leader of social services and became the chairperson of the Central Social Welfare Board (CSWB).

Begum Aizaz Rasul

“Reservation is a self-destructive weapon which separates the minorities from the majority for all time,” said Begum Aizaz Rasul in the Constituent Assembly in 1948. Rasul was born into a princely family in Punjab and was introduced to politics early on.

She was the only Muslim woman member in the Constituent Assembly and advocated for minority rights in a secular state. However, she opposed reservations and separate electorates on communal lines. Beyond the Constituent Assembly, Rasul in the 1990s also believed that given the rising popularity of Hindutva, “it is time to think anew of how to improve the educational and socio-economic conditions of Muslims”.

Rasul was also the President of the Indian Women’s Hockey Federation and established the All India Women’s Hockey Association for 20 years.

Vijaya Laxmi Pandit

Often sidelined as Jawaharlal Nehru’s sister, Vijaya Laxmi Pandit was a diplomat and revolutionary. Born into one of the most illustrious families in India, Vijaya Laxmi Pandit was the first woman cabinet minister in the British era. She was also one of the first leaders to call for an Indian constituent assembly to frame a Constitution.

In the Assembly, Pandit emphasised the responsibilities of a free India towards its citizens and other countries. After independence, Pandit became the face of India on a global stage. She was the only woman delegate at the United Nations Organisation Conference. She was also the first woman President of the UN General Assembly in 1953.

The original copies of the Constitution

Preserving them

Chakshu Roy, January 24, 2022: The Times of India

A little rain in Delhi on January 24, 1950 did not dampen the spirits of the members of the Constituent Assembly. Huddled together, in the Constitution (now Central) Hall of Parliament, they were anxiously waiting for assembly proceedings to begin at 11 am for the last time.

There were two critical items on the day’s agenda. First was the election of the President of India. This one was momentous but straightforward because Dr Rajendra Prasad was the only candidate for the position. The second item was more personal. That day, each member would sign a document that would guide independent India’s destiny — the Constitution of India.

Constituent Assembly members signed three copies of the Constitution. Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru was the first to sign since he had to leave early and Dr Prasad the last. One was a printed copy in English, and two were in English and Hindi hand-lettered by two expert calligraphers. Artists from Shantiniketan also decorated each page of the calligraphed versions.

The two calligraphed Constitution copies are kept in the library of Parliament, and the institution shoulders the responsibility of preserving them for the nation. Their preservation is critical because written documents get damaged by prolonged environmental exposure. Inks and colours fade, plus air pollutants and insect infestation can irreparably damage paper.

In the mid-1980s, the Indian Parliament and the Egyptian government started looking for preservation solutions. The former for the two calligraphed Constitutions, and the latter for 27 royal mummies.

The Egyptians reached out to the Getty Conservation Institute (GCI) in the US. Dr Shin Maekawa, a Japanese-born American, led GCI’s project to design a storage and display case for the mummies. An engineer by training, Dr Maekawa had worked at the NASA-owned Jet Propulsion Lab before joining GCI. He laid stringent design parameters for the oxygen-free cases for the royal mummies. They had to be readily manufacturable, low maintenance and cost-effective.

The Parliament of India reached out to the National Physical Laboratory (NPL) in New Delhi for developing a case for preserving the Constitution. The point man at NPL for this project was its scientist Dr Hari Kishan. He would later go on to head NPL’s Quantum Phenomena and Applications Division.

Dr Kishan would work extensively to fabricate a glass case with some success. The missing piece of the problem was a seal on the edges of the display case that guaranteed it remained airtight and no oxygen could leak into it. While visiting France to develop a glass case, he would learn about GCI’s efforts in designing similar cases for the Egyptian mummies.

Dr Maekawa and the GCI team had successfully made a sealed display case to ensure that minimal oxygen would leak into it over an extended period. In 1993, GCI and NPL agreed to collaboratively design, install and test GCI’s hermetically sealed cases for the preservation and display of the Constitution.

A year later, GCI would ship two display cases for the English and Hindi versions of the Constitution to India. And after a year of testing, the two copies of the Constitution were placed in the airtight nitrogen-filled cases in 1995. Since then, a team of NPL scientists has carried out annual checks on the working of the two display cases.

The work done by Dr Shin Maekawa and Dr Hari Kishan has ensured the preservation of the calligraphed Constitutions that were signed 73 years ago for future generations. While their efforts protect the physical book, the people of India have to preserve the letter and spirit of the Constitution.

As former Supreme Court Justice HR Khanna, who upheld civil liberties during the Emergency, wrote: “A Constitution is not a parchment of paper; it is a way of life. Eternal vigilance is the price of liberty and, in the final analysis, its only keepers are the people.”

Illustrations in the 1st print edition

Art

Avijit Ghosh, January 25, 2025: The Times of India

From: Avijit Ghosh, January 25, 2025: The Times of India

From: Avijit Ghosh, January 25, 2025: The Times of India

It’s a common quiz question, the sort they ask in the early rounds of KBC. Which country has the lengthiest Constitution in the world? Many of us know the answer, as the men and women sitting across from Big B often do. It’s India — 395 Articles, 22 Parts, 8 Schedules — in all, over 1 lakh words in 231 pages.

Not many are aware, though, that the Constitution, crafted under the stewardship of Babasaheb Ambedkar, is also the most artistic of its ilk. No other constitution, art historians insist, visually links its civilisation with its philosophical principles like India’s does. And that’s thanks to the vision of Nandalal Bose and his team.

Now, even as the nation completes 75 years as a republic, the fascinating backstory of the Constitution’s embellishment — the origin of the idea, the engagement and vision of national leaders involved in the project, the artistic devotion and patriotic zeal of the Santiniketan artistes — remains little-known.

Letters written in the last months of 1949 by Ra- jendra Prasad (the year before he became the first President of the new republic), G V Mavalankar (who later became the first Lok Sabha Speaker), Bose and others reveal how there was a frenetic race against time to meet the deadline.

The idea of adorning the Constitution with calligraphy and art came from economist K T Shah, says a Parliament Secretariat note of June 1950. Shah was a graduate of London School of Economics and taught in Mysore and Bombay Universities. Modern India historian Salil Mishra says, “Among the moving spirits in the Constituent Assembly, he had a strong leftward orientation, as Granville Austin points out in his magisterial work, The Indian Constitution: Cornerstone of a Nation.”

This note also reveals how it was at the suggestion of Krishna Kripalani, a notable public figure of the time who also taught at Santiniketan and, later, penned Rabindranath Tagore’s biography, that Prasad wrote to Bose, who was the first principal of Kala Bhavan, Santiniketan’s art school. “…if Shri Nandalal Bose could be persuaded to take the responsibility of directing the execution of the illuminated designs, it would be best,” Kripalani said in her letter to Prasad (who was president of the Constituent Assembly) on Oct 19, 1949. This indicates that a little over three months before the historic event, the Constitution’s art project was yet to begin. Kripalani later headed the Sahitya Akademi during 1954-71.

Bose, a master of blending art and constructive nationalism, was known to and appreciated by most national leaders, especially Mahatma Gandhi and Tagore. Gandhi engaged him in the Congress annual sessions at Lucknow, Faizpur and Haripura.

“He (Gandhi) also said that Nandalal came closest to his idea of an artist. Although the role of art in their scheme of nationbuilding was different, both Tagore and Gandhi thought that Nandalal was the artist they could depend on,” says R Sivakumar, professor of history of art, Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan.

Two days after receiving that note, Prasad wrote to Bose, admitting that “time at our disposal is short”, but also pointing out that “the task was worth doing” because “the illuminated manuscript will be treasured by the nation and by the future generations as a monument not only of our political and intellectual labours but also of the nation’s artistic achievements.” At the suggestion of Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, multi-coloured illustrations were avoided and real gold spray was used for the margins.

Simultaneously, search began for a calligrapher. Two names were shortlisted: Prem Behari Narain Raizada, who worked for Govan Bros Limited, a firm based in Rampur in west Uttar Pradesh. The second was Sarvesh Bahadur Mathur of Jai Hind Flour Mills, Agra. Due to shortage of time, dividing the work between the two was considered, according to a Nov 7, 1949, note by Prasad. But Raizada, who wrote in elegant italics on handmade Millbourne loan paper, was given the sole responsibility of the project. “He used hundreds of pen nibs during his writing,” says Lalit Kala Akademi’s book, Art and Calligraphy in the Constitution of India.

Messrs Govan Bros Lim- ited, a major firm that once had BCCI’s first president, R E Govan, as its managing director, not only permitted Raizada to do outside work, but also paid him his full salary, Rs 325 per month, for the period. The govt provided Raizada, who had learnt the craft from his grandfa- ther, with free boarding and lodging at the Constitution House (now Club) in New Delhi. He also received Rs 1,500 from the govt.

The copies of the original Constitution underline that the artwork colours are subdued in their elegance, much in tune with the sobriety of the larger endeavour. Bose made this a collaborative project at Santiniketan. At least 16 artists were involved, five from his own family. The Preamble and the National Emblem occupied a full page. The illustrations — which adorned the lead page of the 22 Parts of the Constitution — were categorised into themes that were based on India’s history and geography.

They ranged from Mohenjodaro seals, scenes from the Ramayana and Mahabharata, Buddha’s and Mahavira’s lives, Mahabalipuram sculptures, portraits of Akbar, Shiva ji, Guru Gobind Singh, Tipu Sultan and Lakshmi Bai, Gandhi on his Dandi March, Subhas Chandra Bose’s call for freedom, and scenes from the Himalayas, desert and ocean.

In Nandalal Bose’s artistic vision, India’s past wasn’t divorced from the present, rather they walked hand in hand. As Sivakumar says, “their function was to add a historical and cultural background to the Constitution and to remind us that the Constitution is a document for guiding the nation’s future, chosen by a people with a complex and diverse history”.

Painstaking attention was paid to the details. The Lion Capital of Ashoka in Sarnath is the national emblem. The Lalit Kala Akademi book says that Bose wanted the lions in the emblem made for the Constitution to look like real lions with the right facial expressions. “Dinanath Bhargava visited the Kolkata Zoo for months to study lions for their expressions, body language and mannerisms. It was only after Bose was satisfied with the initial sketches that he gave Bhargava the big task of designing the emblem for the first page of the Constitution… On Jan 26, 1950, India adopted Bhargava’s design, the Lion Capital of Ashoka, as the national emblem,” the book says.

Was the work completed on time? Art historian Sivakumar says, “The finishing date is not clear but the work of illumination continued beyond the date of signing and adoption of the Constitution.” On March 2, 1950, Lok Sabha Speaker Mavalankar wrote to PM Nehru, “In the matter of the English copy 2/3rd has been done in respect of calligraphy, while so far as decoration and illumination is concerned only 1/5th is done. As regards Hindi copy, hardly anything is done. Only 1/10th calligraphed and the decoration and illumination is (sic) not yet started.” The Constitution was calligraphed by Vasant K Vaidya in Hindi.

How much were the artists paid? On Feb 19, 1950, Bose wrote to the Speaker, “I undertook the work at the request of our Honourable President and had no idea of the amount of honorarium since I was not accustomed to such undertakings. Of course it is needless to say that our artists did the work out of their artistic interest and patriotic zeal... In conclusion, allow me to state that it has been a proud privilege for the artists of Santiniketan to have been entrusted with this opportunity of serving their motherland.”

For the cover page and the Preamble, the payment was Rs 400 each. For the first page (beginning of the first part), it was Rs 200 and for each ornamented illustration, Rs 100. For each intermediate page with plain decoration, it was Rs 50.

“Calligraphy, decoration, illumination, printing and binding of the two editions of the Constitution will come to be about Rs 1,80,000,” the Parliament Secretariat note of June 1950 says. Over the decades, the Constitution has been fiercely debated and frequently amended. But as a work of art, it continues to endear and endure.

PS: Copies of the original Constitution, in English and Hindi, are preserved in nitrogen-filled hermetically sealed boxes and kept in the Parliament Library.

THE ARTISTS

Nandalal Bose (team leader), Beohar Rammanohar Sinha, Dinanath Bhargava, Vinayak Shivram Masoji, A Perumal, Jagdish Mittal, Rajniti, Dhirendra Krishna Deb Barman, Kripal Singh Shekhawat, Sumitra Narayan, Biswarup Bose, Nibedita Bose, Gouri Bhanja, Jamuna Sen, Bani Patel, and others

22 illustrations

Vandana Kalra, Feb 11, 2025: The Indian Express

These 22 hand-painted images in the Constitution include scenes from the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, pictures of Ram, Mahatma Gandhi, and Subhas Chandra Bose. Nehru was also supposed to be included, but was eventually omitted. All you need to know

The illustrations

While the Constitution was handwritten by calligrapher Prem Behari Narain Raizada, the paintings were conceived and implemented in Santiniketan by artist-pedagogue Nandalal Bose and his team.

When placed in sequence, the narrative scheme of the paintings represents different periods in Indian history, from the Indus Valley civilisation to the freedom struggle, also including scenes from the Ramayana and the Mahabharata.

The illustrations also showcase the diverse geography of India, from camels marching in the desert to the mighty Himalayas. “It is a sequence of images which is his (Nandalal’s) vision of India’s history. He is not illustrating the content of the Constitution, but he is placing the history of India as he saw it. Present-day scholars and historians might have some disagreements about the sequence but that was the broad chronology talked about back then,” said art historian R Siva Kumar.

The appointment of artists

Siva Kumar said Bose was approached with the task of illustrating in October 1949, just before the final session of the Constituent Assembly and the signing of the draft Constitution on November 26, 1949. “It is difficult to say how long the illustrations took and if they were completed before the signing…. in some instances, the signatures breach the space allotted for them and the borders skirt them, suggesting they were added later,” he said.

Two copies of the Constitution, one in English and one in Hindi, are handwritten and bear the paintings. Today, they are placed in a special helium-filled case in the Indian Parliament Library.

Bose was probably entrusted with the task due to his long association with the nationalist movement. A close aide of Mahatma Gandhi, he had designed posters for the Congress session at Haripura, near Bardoli in Gujarat, in 1938.

On the Constitution, Bose worked with a team of collaborators which included close family members, his students and fellow-artists, including Kripal Singh Shekhawat, A Perumal, and Direndrakrishna Deb Burman.

The Preamble page has intricate patterns sketched by Beohar Rammanohar Sinha and bears his signature, while Dinanath Bhargava sketched the National Emblem, the Lion Capital of Ashoka.

Siva Kumar said a note found among Nandalal’s papers suggests that the artists who painted the historical scenes were paid Rs 25 for each page.

It is believed that it was Jawaharlal Nehru who wanted the Constitution handwritten, and therefore Raizada, a graduate from Delhi’s St Stephen’s College, was approached. The calligrapher, who had learnt the art from his grandfather, immediately agreed. Not charging a penny for the task, his only request was to have his name on each page and alongside his grandfather on the last. Allotted a room in the Constitution Hall, he reportedly took six months to complete the task, writing on parchment sheets both in Hindi and English.

The ideation of the artwork

According to Siva Kumar, the text and images in the Constitution have no direct correlation, as Nandalal was not illustrating the text or studying its details while planning the visual narrative. “A preliminary plan was drawn up, which saw deletions and additions,” Siva Kumar said.

For instance, ‘portraits of Akbar and Shahjahan with Mughal architecture’ was replaced with an image of Akbar.

Ashish Anand, CEO and Managing Director of DAG, said: “Nandalal Bose’s career varied across his watercolour washes to his expressionist subaltern works in Santiniketan, and, indeed, the selection and style as well as imaging spans this spectrum in terms of subjects and influences. Illustrating the Constitution was a task that would survive for centuries, an onerous responsibility — and Nandalal Bose’s stamp exemplifies as well as expands the vision of the document it represents.”

Borrowing from history and religion

The Bull Seal, excavated from the Indus Valley region, is the first pictorial representation in the Constitution, appearing in ‘Part I: The Union and its Territory’. ‘Part II: Citizenship’ features a hermitage scene with male ascetic figures offering prayers in a meditative environment. In another scene of hermitage that appears in Part V, Buddha is the central figure, surrounded by disciples, animals, and birds in a serene setting.

Out of the select representations in colour is an image in Part VI of Mahavir, the 24th Jain Tirthankara, seated crossed-legged in meditation.

In Part XIII, we see sculptures from Mahabalipuram and the descent of Ganga to Earth.

Part IV on Directive Principles of State Policy begins with a scene from the Mahabharata, with the discussion between Arjun and Krishna before the onset of the war. For Part III on Fundamental Rights, the artists turned to the Ramayana, drawing a sketch of Ram, Lakshman and Sita returning home after the battle in Lanka.

India’s monarchs

While Emperor Ashoka is seen seated on an elephant, propagating Buddhism, in Part VII of the Constitution, Part IX has a scene from King Vikramaditya’s court with musicians and dancers, representing him as a patron of art.

The only female figure illustrated prominently in the Constitution, Rani Lakshmibai of Jhansi, is sketched in her armour as she shares the page with Tipu Sultan, the king of Mysore, in Part XVI of the Constitution. Chhatrapati Shiva ji and Guru Gobind Singh are featured in Part XV.

“Portraits of Rana Pratap and Ranjit Singh were also meant to be there but were not included probably due to space constraints,” Siva Kumar said.

The country’s freedom struggle

Gandhi appears twice, leading the Dandi March and visiting riot-hit Noakhali in Bangladesh. He is being welcomed by women with an aarti thali and Muslim peasants wearing kufi caps.

In Part XIX, Subhas Chandra Bose is seen against a mountainous backdrop, saluting the flag, with members of Azad Hind Fauj marching ahead.

Nehru was also supposed to be included, but was eventually omitted.

Siva Kumar said three landscapes in the Constitution are a homage to Nobel Laureate Rabindranath Tagore and the National Anthem he composed, which also celebrates the diverse geographical landscapes of India.

Nandlal Bose’ chapter titles

Sep 12, 2019: The Times of India

‘Statute in 1950 form would draw Hindu Rashtra charge’

The Constitution,1950: Part III (fundamental rights) carries a picture of Lord Ram, Sita and Laxman and Part IV (directive principles of state policy) which has a picture of Lord Krishna and Arjun

The titles of other sections have pictures of Lord Hanuman, Buddha, Mahavir, Kabir and even Mahatma Gandhi. There is also Akbar.

Union law minister Ravi Shankar Prasad said [in 2019 that] when the Constitution was being drafted, there were discussions on whether India’s culture, values and traditions should be incorporated into the document. Everybody, including Nehru and other leaders, agreed. “Painter Nandlal Bose was asked to paint the titles of various chapters. The founders of our Constitution decided what the paintings would be,” he said.

The architects of India’s Constitution

Fifteen founding mothers

Manimugdha Sharma, March 8, 2020: The Times of India

From: Manimugdha Sharma, March 8, 2020: The Times of India

Leela Roy was a socialist revolutionary. At a time when revolutionary activities were understood to be a male bastion, this Assam-born, Bengal-raised woman had in the 1920s taught other Bengali women how to make bombs, handle firearms, and circulate ‘seditious’ pamphlets. In 1946, she was elected to the Constituent Assembly, becoming one among 15 women tasked with framing a Constitution of free India.

Over the decades, the role played by these women who rocked the cradle of the nascent Indian republic was forgotten. Until now.

Priya Ravichandran, a marketing professional from Chennai, has been digging out the stories of these founding mothers of India as part of a project that she hopes to turn into a book.

The stories are fascinating. Roy, for instance, quit the revolutionary path and became a member of Indian National Congress in 1939. Then she became a member of Subhas Chandra Bose’s Forward Bloc. In 1942, she took part in the Quit India Movement and was arrested and jailed. “She quit the Constituent Assembly too in protest against Partition. And so did Malati Devi Choudhury,” Ravichandran says.

Choudhury was a Marxist. And she quit because she was uncomfortable with the idea of a constitution that was so heavily borrowed, elitist and inorganic. “There was also a strong belief that despite the granting of adult franchise, the ‘uneducated, poor, & hungry’ were not going to be alleviated, and that the Constitution would not go far enough in giving them a voice. The long, often contentious discussions and drawn out procedures would not have appealed to the restless nature of a woman whom Gandhi nicknamed “toofani”. She stepped away soon after to heed Gandhi’s call for a peace march for Noakhali and to work with the ‘Namasudras’ of Tripura (an avarna group),” Ravichandran says.

Historian Namrata Ganneri agrees that these women have been underrepresented in the national narrative. She says that many of these women had substantial careers before they stepped into the Constituent Assembly. So, they weren’t showpieces in the assembly but strong voices that challenged the status quo. “Women like Renuka Ray who were instrumental in the Hindu Code Reform were stridently opposed by a section of conservative women. Jankibai Joshi, who was president of the All India Hindu Mahila Mahasabha, decried Renuka Ray’s interventions as that of a Brahmo and not representative of a large majority of Hindus. Divorce reform was particularly opposed as western and destroying the sanctity of Hindu marriage,” Ganneri says.

For Ravichandran, it was Durgabai Deshmukh that led her on this quest. “The road I take to work in Chennai is named after her, and I also pass by her brainchild — the Andhra Mahila Sabha. My curiosity about her work and life kickstarted this interest, which is now a full-blown obsession,” says the researcher.

She also says that it took quite a bit of effort to figure out how exactly these women came to be in the assembly and how they contributed to the republic. “For many of them, the personal was intensely political. Vijayalakshmi Pandit, for instance, was directly impacted by property laws when she lost her husband in 1944. Her experiences went to inform her acts when she championed for the reform of Hindu women’s rights in All India Women’s Conference. So, to be able to map these connections, and parse the relationship between the women was challenging. Quite a few of them went completely off-radar after the 1950s, which hampered the search,” Ravichandran says. Till she embarked on this quest, the Indian republic for her was one built by men, with women on the sidelines. “Sarojini Naidu and her poems, Kamala Nehru and her protests, Kasturba Gandhi, Annie Besant, Aruna Asaf Ali, Lakshmi Sehgal etc are well known but there were these women too: Aruna Asaf Ali’s sister Purnima Banerji, Sehgal’s mother Ammu Swaminathan, all playing a central role. How could we not know about them? How can our understanding of our country be one written by men, and of men?” Ravichandran says.

Difficult circumstances under which India's Constitution was adopted

India’s deceptive Constitution= The Hindu, November 26, 2015

The written Constitution diverges to such an extent from Indian constitutional law that it is not just an incomplete statement but can be positively misleading

Here's a look at the difficult circumstances under which our Constitution was adopted:

1. 271 men and women who were part of the Constituent Assembly, drafted the Indian Constituion after three years of debate over the governing charter of India.

2. The Constitution consists of 90,000 words carefully handwritten in English and Hindi. The books were also illustrated with events from Indian history exquisitely prepared by the great national artist, Nandalal Bose of Santiniketan.

3. There were no foreign consultants involved in framing the Constitution. The founders were adamant that Indians should have full control over the drafting procedure. Thus, the assistance of several lawyer-members were sought: Nehru, Prasad, Ambedkar, and Alladi Krishnaswami Ayyar were part of the historic draft.

4. Based on expert inputs, the Assembly's Constitutional Adviser B.N. Rau prepared an initial draft constitution in February 1948. Rau's draft was further revised by Ambedkar's drafting committee and issued in November 1948.

5. The Assembly took almost a year to discuss it. More than 2,000 amendments were considered and several were accepted. The drafting committee produced a revised draft, which was eventually adopted by the Assembly, with some changes, as the Constitution on November 26, 1949.

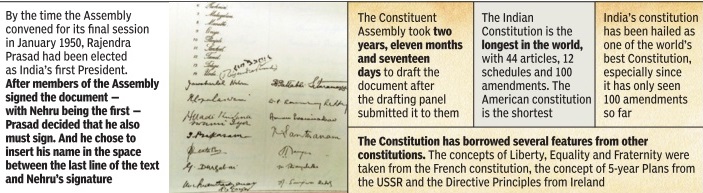

6. When the Assembly convened for its final session on January 24, 1950, its secretary, H.V.R. Iengar announced that Rajendra Prasad had been elected unopposed as India's first President. He invited members to sign the Constitution's calligraphic copies. Nehru was the first to do so and members from Madras followed him.

7. After the last member had signed the books, Prasad decided that he, too, must do so. But, rather than signing behind the last signatory, he inserted his name in the small space between the last line of the text and Nehru's signature.

8. Two days later, the Constitution became fully effective. At a ceremony held in Rashtrapathi Bhavan's Durbar Hall, Governor General Rajagopalachari solemnly proclaimed India as a “Sovereign, Democratic Republic”.

9. Through its unprecedented abolition of untouchability, the Constitution serves as a powerful emancipation proclamation ending centuries of caste-based discrimination and social exclusion.

10. The Constitution expressly guarantees every citizen important fundamental rights, which may be subject to only certain restrictions. These rights include the ability to freely speak and express oneself; the freedom of conscience and to profess, practise, and even propagate a religion; basic protections against arbitrary arrest and detention by authorities, and various cultural and educational guarantees.

The making and implementation of the Sublime Constitution

Nov 27 2015 : The Times of India (Delhi)

STATUTE OF LIBERTY - Constitution is sublime, failings are of our own making

Harish Salve

As a college student, I remember hearing a speech by the legendary Palkhivala on what he called “the Sublime Constitution“. There can be no doubt that the epithet coined by him was anything but fully deserved. The government's decision to characterise November 26 as Constitution Day is a remarkable step -albeit a token of gratitude which this nation owes to one who can fairly be called the principal architect of the Constitution.

The framing of the Constitution was a painstaking exercise. On August 29, 1947 the Constituent Assembly appointed a drafting committee (B R Ambedkar was chairman) which presented a draft in February 1948. This draft was discussed and altered and finally adopted by the Constituent Assembly on November 26, 1949. The Indian Constitution drew upon models in countries such as the US, Australia, Canada, Ireland, but crafted its own architecture.

Ambedkar in his speech to the Constituent Assembly quoted the powerful words of Grote [the Greek historian] “...The diffusion of constitutional morality.... Is the indispensable condition of government at once free and peaceable...Since even any powerful and obstinate minority may render the working of a free institution impracticable even without being strong enough to conquer ascendancy for themselves.“

With his characteristic bluntness Ambedkar said: “Constitutional morality is not a natural sentiment. It has to be cultivated. We must realise that our people have yet to learn it. Democracy in India is only a top-dressing on an Indian soil, which is essentially undemocratic.“