The Meitei Language and Grammar

The Meitei Language and Grammar

This long section is an extract from THE MEITHEIS T. C. HODSON Late Assistant Political Agent In Manipur And Superintendent Of The State Fellow Of The Royal Anthropological Institute With An Introduction By SIR CHARLES J. LYALL K.C.S.I., C.I.E., LL.D., M.A. Published under the orders of the Government of Gastern Bengal and Assam Illustrated LONDON David Nutt 57, 59, Long Acre 1908 Indpaedia is an archive. It neither agrees nor disagrees |

The Meitei: Traditions, Superstitions And Folk Tales

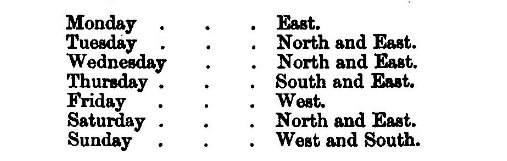

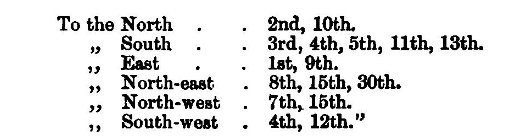

Dr. Brown has recorded some of the superstitions then current among the Meitheis in the following passage : * " The Munni- pories are very superstitious. Demons of all kinds inhabit the small hills and other parts of Hie valley. They are also extremely superstitious with regard to days and dates for setting out on journeys in diflferent directions, although on emergencies these ideas are put to one side. The following are unlucky days and dates for travelling in diflferent directions —

The dates upon which it is unlucky to travel are as follow-

It is clear from the Chronicles that Manipur is a land where strange things are in the way of happening. Now a God fires off a cannon, it may be that to-morrow two stars will rush together or that thunder will thrice be heard in a clear sky, an occurrence which from the times of Ovid we know portends the near approach of some great event. It is a land peculiarly liable to seismic disorders, and all the folk cry out aloud " ngd cJiak," " fish and rice," in order to save their food supplies from the demon who is shaking the earth« Eclipses are due to the attack of the demon dog upon the sun or the moon, a story which is more fully explained by the Kabul version. At the death of Major Gordon in 1844, so the Chronicler records, a double- tailed star was seen in the sky, and in another passage the death of the eldest son of the Raja is connected by a sort of post hoc ergo propter hoc argument with an earthquake which occurred simultaneously. It is common to read of inanimate objects suddenly manifesting the power of locomotion. Stones raise themselves, guns fire themselves, drums beat themselves, the Eoyal cloth upon the loom shakes itself. Yet these things are the work of some Deity, for stones are well-known to be often chosen by Deities as places of abode, and if the divine inhabitant is displeased by being forcibly taken from some similar spot, he will show his wrath and produce a scarcity of food. The Royal cloth is destined for a being who is regarded as a God incarnate, and what he wears, or even what is destined for his wear before he has actually worn it, acquires something of his divine power. Rainbows have been known to form around the Royal head, and the very bow and arrows of the Rain God floated in the water of the moat close to the boat in which the Raja was sitting. This, of course, was an omen of exceptional felicity. But when rain fell like clay, when blood was found on the floors of the temples, when four suns were seen in the heaven, misfortune awaited the country. Sometimes we are enabled to assign to an omen a definite meaning, as when a swarm of butterflies is seen coming from the west to the east or when rooks fly from north to south, trouble in the shape of epidemic disease is at hand.

The mysterious portent described in the phrase sangaisel paire or the flight of the sangaisel, betokens the death of some rich and important personage. It is not easy to ascertain exactly what is meant by the expression. One passage of the Chronicles says it is the flight of the spirit of a certain God, while in another it is said that a flame arises out of a holy stone, and I was informed that it was accompanied by a mysterious noise. We have in Colonel McCulloch's account the following reference to the supersti- tions of the Meitheis in regard to the erection of their houses : * " Connected with the making of their houses are many superstitious practices. First, the house must be commenced on a lucky day, that day having been fixed by the astrologer ; on it (it makes no diflference whether the other materials are ready or not) the first post is erected. The post is bound towards the top with a band of cloth over which is tied a wreath of leaves and flowers. Milk, juice of the sugarcane and ghee are poured upon the lower extremity and into the hole in the ground in which it is to be fixed are put a little gold and silver. The number of bamboos formings the body of the frame for *the thatch must not be equal on the north and south sides. K they were so, misfortune, they consider, would overtake the family. The other superstitions of the same kind are too numerous to mention. And it is not merely in reference to their houses that they are superstitious ; they are so ia every matter. Super- stition constantly sends them to consult their maibees and 'pundits, who earn an easy livelihood by prescribing remedies to allay their fears." It will perhaps show the exact care and anxiety with which all house-building operations were carried on if a quotation is made from the Chronicles of a passage which describes the trouble which happened when something was done which ought not to have been done in the course of the erection of the kangla or Eoyal enclosure of the Coronation Hall. This is, of course, a peculiarly sacrosanct spot, not only from its association with the Raja, but as being the abode of the serpent as well. On the 15th of Mora, Sak 1771, i.e., in October, 1849, Lairel Lakpa the astrologer declared that the place selected by the pandit for the site of the main post of the kangla was wrong because it would interfere with the place of the snake annanta. The pandit had his way and the hole was dug with the result that blood issued, and a bone and a stone were found there* Some days later the post was erected, but that night a white rainbow was seen over the post. The next day a snake entered into the hole where the post was and there was a frog on the back of the snake. Weeks later the king elephant went mad, and on the 5th of Hingoi (November) a fisherman at Wabagai caught in the trap a fish which he put in his bag. He was surprised to hear the fish say to him, " You want to eat me. I am the lai of the river." The fisherman replied that he had caught him in ignorance of his real rank. The fish then said^ "Go and tell the Maharaja to do worship on behalf of all the people," and jumped back into the water. A swarm of bees was seen at the gate of the Fat, and Lairel Lakpa declared that all the " bad signs of the kangla had appeared," and then a trial was made of the value of the books of the Pandit and the astrologer Lairel Lakpa. The test was which book correctly gave the depth at which in the reign of Moyang Ngomba Maharaja the stone of the tortoise or snake Pakhangba was found. The book of the Pandit proved trustworthy, and then the evil omens ceased to appear. Indeed, according to the Chrouicles hardly an event of real importance ever occurred without some previous presage. Thus the shortness of the reign of Debendro Singh was foretold by the death of the king elephant and by the appearance in the Jcangla of a number of frogs which were seen there jumping about. The end of the dynasty of Gambhir Singh was foretold by a number of omens which are recorded in the Chronicles. " On the 13th of Kalen in the year 1813, the year of Ahongsangba Durlub Singh (1891, April). In the palace here a God's dolai with flag came down from the sky before the Bejoy Garode at ten o'clock in the morning ; it disappeared at the distance of 40 feet from the ground : the people witnessed the scene. The matter was reported to the Maharaja next day. The Maibas and the officers of the Top Garode were summoned before the Maharaja, who asked Wikhoi Pandit what sort of dolai it was. Wangkhai (or Wikhoi) Pandit replied that it was Pakhangba's dolai. Pakhangba's nine arms will come down in koongkhookolen (the kangla compound). The dolai was the first thing that had come down, and after this the country would enjoy happiness and peace, and the king would live long. Nongmaitemba Pandit seconded him and urged the Maharaja to worship Pakhangba. Touria Ashoiba Hidang re- plied that their prophecy might hold good, but it appeared to him that a calamity was coming.* Naharup Lakpa upon this said that Touria was in terror and could not calculate properly. Men said in Maharaja's Sur Chandra's time that Maharaja Chandra Kirti Singh was ordained to reign for forty years, but

- Note the British troops had already reached the valley to avenge

the murder of the Chief Commissioner and his companions, and this was known to all present.

The ceremony of ascending the throne (phamban kaba, or climbing the seat ; phamban, from phamba, to sit, and kaba, to climb) was pregnant with varying incidents, all of which had their special significance. The Raja and Rani, clothed in the garb of an earlier age,* passed from the house t (sang kai punsiba) within the walls to the kangla without, and as they went, careful note was taken of the stones on which the Kaja trod. The Panji Loisang J then read from them prognostica- tions of the reign. Then in the recesses of the kangla was a chamber in which was a pipe leading, so I was told, to a chamber below, wherein dwelt the snake Pakhangba. The longer the Eaja sat on this pipe and endured the discomfort of the unaccustomed pose and the torture of the fiery breath of his ancestor below, the longer and the more prosperous would be his reign.

The story of Numit kappa is a folk tale, and its peculiar interest may afford an excuse for the literal translation which I now give.

Numit Kappa (The Man Who Shot The Sun)

"O my Mother, Mother of the Sun who is the Father of the world, Mother of all the Gods. She who was the Mother of the World gave birth one day to three sons. The first-bom son was destroyed like withered paddy, and became like old dry paddy, and entered into the earth, and became even as the ant- heaps. Thereupon the Lairemma paddy and the great paddy were turned into Morasi and Iroya paddy. Her second-born son became rotten even as chicken's eggs, he became as the darkening rainbow. His eyes became like unto the eyes of a deer. Her third-born son was called Koide Ngamba, the younger brother of the Sun. He was of a haughty temper and quick in spirit. He fell into a fishing weir and was killed. Thereupon his teeth became like the teeth of a wild beast, his rib-bones became the long dao of the Gods. The hairs of Ids head became like the flowers that men oflfer to Purairomba and all the Gods. They became even as the flowers that men fasten on the ends of their spears to catch luangs (small hill fish) in December, or like to the flowers that the King's wives and children present to the fields, such fiowers as the Ang5m Ning- thou daily offers up, even as such became the white hairs of the God.

Now the Sun and his brother Taohuirenga rose and set alternately. There was a man Khowai Nongjengba who had a slave, a lazy churl named Ekma Haodongla, who was wroth because the suns rose and set alternately. He said, 'I am a slave and twice have I to fetch wood, twice to bring in my master's paddy on my head. I cannot rear my children. I cannot see my wife, So he said to his wife, ' My dear, go, get a bamboo from your father.' But her father would not give her a bamboo. ' Go to your uncle and beg a bamboo from the Thongkhongkhural, a bamboo that grows on the Khural King's Sokpa Ching.* Thus he said, and sent her off. The Ehural Lakpa gave him a bamboo from the hill. The slave of Ehowai Nongjengba Piba in five days made a bow and arrows, and when he bad dried then^ he smeared the tips of the arrows with poison, and put the arrows in the quiver and rested. Then he said, 'Dear wife, Haonu Changkanu, my pretty one, go draw water and put the pot on your head. Then as his wife came from the water, he aimed and hit the pot on her head. One day he aimed and hit the hole in her ear. One day he aimed and hit a sparrow sitting on a heap of dhdn. * Wife, make food ready. A big boar has entered the field, a great python has come into the field. I will combat those strong things. I will kill that boar.' He slept by the side of the things he was going to take to the field, and for this reason the place is called thongyala mamungshi. The Great Sun set at Loijing. His elder brother Taohuireng arose in his splendour, and Ekma Haodongla the slave of Khowai Nongjengbet Piba, a lazy churl, drew the string to his cheek and though he fiied the arrow carefully at the sun, he hit the sim's horse on the leg, and it fell near the great Maring village. When the bright sun fell by the arrow of the slave of Elhowai Nongjengba Piba, he was afraid and hid himself in the earth in a great cave by the big village near his father Pakhangba and his mother Senamehi. Then the Meithei land was dark by day and dark by night. The fields and the whole countryside looked to the Gods for pity because the day remained not. Weeds grew. Women that used to go to the fields went no more, women that used to toil in the fields went no more. The ten kings (Nongpok, Chingkhai, Wangpurel, Khana Chaoba, Thangjing, Sampurel, Loyarakpa, Kaobaru, Kaoburel, Marjing), these ten gods knew not how to look for the place where the sun was. A woman going to the field was holding converse with a woman going to sow, * My friend, my companion, what is that fire in the earth shining there over by the great village ? ' said she inquiring. ' Yes, my dear, the Sun is hiding near his father Pakhangba and Senamehi.' * It is the brightness of the Sun,' said the other as they talked. The ten Gods heard, and when they had returned to their own house, they called Thongnak, whose dreams were very true. ' Thongnak Lairemma, your dreams are very true, a dead person has entered into you. You do judgment on the dead. Call the Sun.' With these words they sent her. Thongnak Lairemma called the Sun. *0 Sun, by reason of thy disap- pearance, the land of the Meitheis is in darkness day and night. Bring thy warmth over this land and over its villages.' Thus said she, and the Sun made answer to her. ' Yea, Thongnak Lairemma, formerly my Mother, who is Mother of all the Gods and the Mother of the world, gave birth to five sons. One day my eldest brother shrivelled up like dry paddy and was destroyed. My second brother became rotten like the eggs of a fowl, my brother Koide Gnamba fell into a fishing weir and was drowned. Now my elder brother Taohuirengba has fallen by the arrow of the slave of Khowai Nongjengba Piba, for his horse was pierced through the leg by the arrow which he shot, and so he hides in a dark cave.' Thus he spake, and would not come forth. Thongnak Lairemma returned to her abode. ' Ye ten Gods, hear. The Sun cannot remain alone in the world.' Then the ten Gods hired Panthoibi, the daughter of the King, the wife of Khaba. * daughter of the King, who art beloved of the King of the country, who causest to be bom all the souls of men and dost cause them to die, who art the Mother of the Gods and the Mother of all the country, thy face is beautiful, do thou go, do thou call thy Father the Sun.' When they said this, the King's dear daughter who causes a tiower to bloom merely by touching a big white leaf, assented to their request. * Ye Ten Gods, if ye bid me to persuade the bright Sun to come forth, make ready the roads, make men to go to and fro, build a nuichan five stories high, make the women all join in entreaties to him. In the baskets spread leaves carefully and set therein white rice, put eggs, fill the wine jars full of wine, wrap ginger in leaves and set it down, wrap cowries up in a black cloth and put them down near/ Then she took a white- cock and all the other things and went to the broad country to persuade the bright Sun.

" *O Sun, by reason of your hiding, in the land of the Meitheis there is darkness night and day ; by your brightness warm all the country to Imphal from here.' Thus she said and thus she persuaded him, for he assented, and when the white fowl lifted up its foot on the earth, the Sun also raised his foot firom the earth five times and clT ^ed to the top of the mcichan. Then the ten Gods looked and saw that the sunshine was pale. ' Let us make this right,' they said. Then Pakhangba's priest sat on the right, and the priest of Thangjing, the G^ of Moirang, sat on the left. They took water fix)m the river of Moirang, and an egg and yellow grass, and drew water from the top of Nongmaiching, and the priests, the children of the Gods, made the face of the Sun right, and his eyes and his Sbm^ were bright and beautiful. Panthoibi holding the fowl soothed the Sun. Then the priest, who formerly guarded the seven branches of Nongmaiching, and who lived on that holy hill, whose name was Langmai Khoiri, who formerly worshipped the £skce of the sun, made prayers to the Sun. ' Thou hast come like the eyes of the hill. In the likeness of the eyes of the hill in thy brightness thou hast pitied us, the villages of Nongmaiching. like the eyes of the Sun thou hast come. Like the eyes of the Sun by thy brightness the warmth of the sun has warmed all the ravines and jungle and all our villages on Nongmaiching.' Thus said he as he prayed. The great village also made prayers to the Sun, and its priests sang and prayed. The women also of the great village have crossed the river and have gone to the fields. The Tangkhuls have taken up their daos. Men see their shadow in the water. ' By thy brightness all the paths and all the trees and all the bamboos in our great village are warm with the warmth of the sun.' Thus said he and prayed. Then the brothers, the cunning priests, slaves of Thangjing, prayed to the Sun God, ' thou bom on the stone, bom on the white stone, who lightest the jungle, and the water, and who shinest up to the top of the loftiest bamboo, with thy brightness make warm the heat of the sun on the water of Moirang, In the south the Khumal priest prayed. His father and his forefathers were very skilful, and his voice was very good, and his singing carried far. Than him there was none greater, his voice was like the cry of the crane, and in his singing there was no fault. Thus prayed he. ' Sun, now that thou hast come, the trees, the bamboos, the grass, all are bright. Sun by thy glorious brightness the leaves and the wood are as new, the heart is glad. By thy brightness make warm the heat of the sun upon the land of the Khumals, Then the priest of the King of Manipur, who was skilled in the songs of the Manipuris, whose voice was like the running water, invoked by name his deceased mother, and singing sweetly the name of his dead father, having sung the names of men that were dead and making them to unite in the history, he makes birds and crows that are dead to be among the Gods. He knows the souls of men and their names, even though they are lost,* he knows them when they have become animals, though their names should be forgotten, he calls them in his song. Though hereafter the names of men be forgotten, he in his wisdom knows them, though they are wandering in the abyss among the demons, even though they have joined themselves unto swine, he knows them. Thug made he prayer.

- Sim, Thou alone art beautiful, thou art the Father of all the

unfortunate, thou art deathless, there is none like thee for truth and beauty. I cannot tell all thy names in my song, so many are they. Thou art the source of all good fortune, for in the scent of the earth is seen the warmth of the sun. Bright Sun, thou art the source and the strength of all the world and of immortality.' "

Dr.Grierson gives the following folk tale in the Eeport of the Linguistic Survey of India f : —

" Once upon a time a man had two sons. After some time he died leaving behind him a buffalo cow, a pomegranate tree, and a curtain. When the two brothers proceeded to divide the

- Mang = to be lost, or ceremonially polluted

property, the younger brother, who was the more clever of the two, arranged the matter in the following way. He gave the front part of the buffalo, including the head, to his elder brother, and retained himself the other half, from the tail and forwards. And he gave his brother the lower part of the pome- granate tree, and took himself the top. With regard to the curtain, he used it at night, and left it to his brother during the day time. When the buffalo ate the crops of other people he made his brother give damages, because the outrage was done by the head, which belonged to the elder. But he claimed for himself the calves which were bom and the milk. And he also reserved for himself the fruits of the pomegranate tree.

"In this way some time passed. The elder brother was advised by the neighbours, and one day he went to fell the pomegranate tree in order to get fuel. But the younger brother now proposed that they should divide the fruits between them, and thus prevented the felling of the tree. Now the elder brother declared that he would kill his part of the buffiedo because it gave him such trouble in eating the crops of other people. The younger brother then stopped him, saying that they might also take each his share of the milk and of the young buffaloes. Then the elder brother took the curtain and kept it during the day in water. The other then proposed that they should use the curtain alternately. Both agreed, and after that time they lived without quarrelling."

The History Of Moirang

Moirang was created by the God, Thangjing, who came down from heaven in the shape of a boar. Seven times did he in- carnate himself and rule as King of Moirang. The first King of Moirang at the beginning of Kaliyug was Iwang Fang Fang Ponglenhanba, who was bom of Moirang Leima IN'angban Chanu Meirapanjenlei. He attacked Naga villages, brought Thang* nnder his rule, and fixed his boundaries to the north, where tta Luang King bore sway. He brought in captives, and buried the heads of his fallen enemies in the Kangla or Royal endosuie. Then the God Thangjing bethought himself that the King and his subjects were so prosperous that they were likely to forget their duties to him, and after taking counsel sent seven Gods, Yakhong Lai, to frighten the King and his people. At night there were mysterious sounds, but the soldiers at first could find no one. Then, when the sounds occurred a second time, they became aware of the Gods, the Yakhong Lai, and reported what they had seen to the King, who took counsel of his ministers- They besought him to call the famous maibi Santhong Marl Mai Langjeng Langmei Thouba. She was in the fields culti- vating, but came running, whence (says the historian) all the dwellers of Moirang say apaiba, i.e., " to fly," instead of chenha, " to run " which is the ordinary Meithei word.* The King begged the maibi "very respectfully" to raise the Khuyal Leikhong which the angry storm raised by the Gods had blown down, and by way of showing his respect said : " If you cannot raise the Khuyal Leikhong, I shall kill you." The maibi persuaded the seven Gods to tell her the mantra, and ordered her to convey a message to the King, who was bidden to send all the maibas and maibis of the country to sleep in the temple of Thangjing wearing their sacred clothes. When she went to the Khuyal Leikhong she saw Pakhangba there. She raised the edifice by means of the mantra and then gave the message to the King, who bade the maibas and maibis go and sleep in the temple of Thangjing in their sacred clothes. There in their dreams they were instructed to divide the people into sections, some for one duty and some for others. Then the village ofi&ces were created and their order of precedence fixed. The m/zibas chant the name of the God and the maibis ring the bell. Then, when they had told the King all the wonderful things communicated to tiiem in their dreams, they were bidden to do as the God had said. Then the King died and was succeeded by his son Tel- haiba, so called by reason of his skill with the bow. In his, and in the following reigns, there were raids against Nagas and various villages. Then we get into complications, for in the reign of King Laifacheng we are told, the Khumals were wroth with

- The logic may be deficient, but we may compare this statement with

the fact that in the Royal Meithei vocabulary the word to walk to go*' is lengba, which in Thado means to fly.'* The incident proves, firstly, a dialectical variation, and secondly, the imposition of a tabu on the use of the word chenha by the people of Moirang. Konthounamba Saphaba and compassed his death. They took him into a wood and fastened him to a tree and left him, but by the aid of the Gtods he broke the creeper and made his way to Moirang where he married and had a son« He left Moirang, and went to the land of the MeitheL The King kept the child, who by favour of the God Thangjing grew so strong that the folk of Moirang begged the King to rid himself of the lad, for he would supplant the King. So they put the lad in chains for seven years, and all that time there fell no rain in Moirang. Then the God Thaugjing appeared to the lad and told him to ask the King to take off his chains. Then the King set the lad free, and the rain fell, but many had died of fever and cholera. The King implored the lad to pardon him for his cruelty and promised him, that when he was dead the kingdom shoidd be his for seven years, even as many years as the years of his bondage. So it fell out, and for seven years the lad rdgned as King where he had been in chains.

Raids against Luangs on the west against Naga villages, which the historian observes still pay tribute to Moirang, are all we have for a brief space covering some hundred years. The God Thangjing kept his interest in the fortunes of the kingdom, and visited the King in his dreams and instructed him in many matters. The village grew and spread, so much so that in the reign of King Thanga Ipenthaba the small hill of Thanga was broken and the water let out. Then at the instance of two Khumal women the King slew the King of the Khumals whom he met by chance hunting. In a later reign, Moirang is invaded by the Khumals who assembled a force in boats. This force was defeated, and in return the Khumal villages were foed.

In the reign of King Chingkhu Telhaiba (skilful archer of the hill village), a Khumal, Aton Puremba, shot nine tigers with his bow and arrows and brought their skins to the King, who sought a gift worthy of the hunter's prowess. He would not give him clothes or such things. He had no daughter, so he gave him his wife, and by her the bold hunter had two children Khamnu and Khamba. Both their parents died, and by dint of begging from door to door, Khamnu got food for herself and her baby brother. Day by day the lad grew in strength and courage. So swift was he that none could race against him. So strong was he that he and he alone dared to seize a mad bull that was raging in the land, Then Chingkhuba Akhuba, brother of King Chingkhuba Telhaiba and uncle of the Princess Thoibi, ordered his men to seize Khamba and have him trampled to death by the elephant. His sin was that Thoibi had made a coat which she gave to Khamba, for she loved him. The (Jod Thangjing warned Thoibi of the peril in which her lover was, and she arose and threatened to kill her father so that Khamba escaped. Then it befell a hunting party that a tiger killed a man in full sight of the King, but Khamba killed the tiger single- handed, and as a reward the King gave him the Princess Thoibi in marriage.* In 1431 the Meithei King slew the King of Moirang (at the battle of Moirang-khong in Imphal where there is a tumulus beneath which are buried the heads of the Moirang tribesmen that were slain in the fray). The later entries consist of names of persons who became Kings, and against one name is the remark " King Chandra Kirti Singh dismissed this King, and for twenty-seven years there was no King of Moirang." Last of all is the entry, " In 1813 Shak the Political Agent of Manipur appointed Eomanando Singh as Moirang Ningthou."

One or two points occur. All the early Kings marry women of the Moirang clan, while even the change of the dynasty, when the son of the Khumal refugee became King, is not an exception, for the mother of TJrakonthouba was a Moirang woman. Later on there are failures in the direct line, but a brother is recorded as successor. The incident of Khamba and Thoibi has no doubt been worked in by the chronicler, who seems to share the view held by Thangjing that the people are forgetting their religious duties and need to be roused by some calamity.

More than ordinary interest attaches to the proof here afforded of the manner in which the divine ordinances regu- lating the structure of society and apportioning the duties of the citizens were promulgated as the result of dreams by the maibas and maibis — the soothsayers and wise women.

In conclusion it may be pointed out that there exists in Manipur a store of written recoi-ds which, apart from historical value, possess an ethnological importance as afifording, un- consciously and unintentionally, remarkable evidence as to the level of culture from which as yet the bulk of the population has not emerged. There is yet a rich harvest to be gathered in, and, if the workers are few, their labour will be justified by its reward.

Khamba And Thoibi

(The superior figures refer to the iwtes aJt the end of this tale,)

In the days of Chingkhu Telheiba, King of Moirang, Ching- khu Akhuba was Jubraj, and his brother the King had no child. The daughter of the Jubraj was Thoibi Laima. And in those days Yoithongnai was King of Khun^al and he had three sons, Haoramba-hal, Haoramningoi and Haoram-th5l Louthiba. On a day it happened that Panji Thoiba, the King's soothsayer and his wife, Chaobi Nongnangma-chak, went fishing in a lake at the foot of a hill whereupon there grew a Heibung tree. As the soothsayer rested in the shade of the tree, he saw thereon a necklace of beads which he plucked down and gave to his master, the Khumal King, who set it on the neck of his son Haoramba-hal. Then, as the King grew old, he set the neek- lace upon the neck of his second son, and then, last of all, upon the neck of his youngest son Haoramba-th5l.^ In these days the Luang King Funsiba built him a new palace and summoned all the Kings to the great feast upon the day when he was minded to enter therein. So the sons of the Khumal King, Haoram*hal and Haoram-yeima were bidden, and put on their robes of State. And Haoram-hal entreated his mother to lend him thenecklao6y and she hearkened to his entreaty. Soon Haoram-thOl came home from his sport in the village and found not the neoldaoe though he sought for it diligently. Then he was wrath and took his father's sword and sought his brothers so that he might kill them. Yet to none did he declare his purpose. So he met his brothers by the way and slew his brother Haoram-hal, for on his neck was the necklace, and Haoram-yeima fled to Moirang, where he took two women unto him as wives, and they bore him each a son. Now Parenkoiba was the son of the elder wife, and Thangloihaiba was the son of the younger wife. In his days Parenkoiba took unto him a wife, and she bore him a son whom they called Purenba, and in his days he took unto him a wife, and his wife bore him first a daughter whom they called Khamnu, and thereafter a son whom they called Khamba.

Now it chanced that upon a day King Chingkhu Telheiba of Moirang went a hunting in the jungles, and when the men fired the reeds, five tigers rushed out, and the men who were with the King fled, all save Purenba who slew the tigers with his spear. So the King gave him his wife, for daughters had he none. And with her he gave rich dowry, even a store of goodly apparel, and he set the brave man in high ofi&ce with titles of honour that all the folk might know his fame.

Thereafter the King's soothsayer* chose the names for the children that his wife bore unto him, and the King assented to the names. Then it chanced that Purenba fell ill, for an evil spirit entered into him ^ so that he was vexed with a fever and died. Ere he died he sent for his friends, Nongthonba and Thonglen, and commended his children to their care, and Nongbal Chaoba betrothed his son Feiroyamba to Khamnu.® Then his wife, seeing that her husband was indeed dead, could not live when her lord and husband was taken by death from her. So she slew herself upon his pyre, and Thonglen took charge of the two children, but they sorrowed and would not be comforted. So he let them go, and they went to their father's house, and were happy there. But there was none to help them, so Khamnu went among the village folk and husked paddy for them while the women gave the breast to Khamba. Then one day it fell out that Khamnu went to Moirang to the bazar at the very hour when the Princess Thoibi was wont to do her marketing, and the Princess took note of the strange face, for she knew her not and asked her many questions and gave her gifts of food and jewellery ; but Kiamba was vexed, for there was nought for him. Khamnu met Thoibi again, who bade her come afishing with her on the Logtak. When the King heard that the women who bore his daughter company were minded to sport on the lake, he gave orders that no man might go on the lake. So Khamnu told Khamba of this and left him at home the next day. As he slept. in his dream the Goddess Panthoibi came to him in the guise of Ehamnu, and bade him get the vegetables together. Khamba woke and wondered if he had indeed seen his sister or if it was a dream, but the God Thangjing put it into his mind that he had indeed seen his sister. So he went down to the lake and got a boat there and rowed out, but in a wrong direction, so the God spread a veil of cloud over the hill. Anon a storm arose and blew the boat towards the place where Thoibi was fishing. On a sudden Thoibi turned and saw Khamba standing close to her. She asked ELhamnu if she knew the stubborn man who dared disobey the orders of the King, but Ehamnu denied all knowledge of him. Khamba stood there not knowing what to do, but when he heard his sister's voice, he went nearer, and Thoibi saw that he was goodly and well fashioned, as if daintily carved by some master hand. Khamba, too, wondered at the beauty of Thoibi, for it was the will of God that they twain should love. Yet again Khamnu denied knowledge of the man, for she feared for him that he would be pimished for disobedience. Then Thoibi saw that Khamnu was wearing a piece of cloth which matched Khamba's pagriy and that Khamba wore the bracelet which she herself, but a day before, had given to Khamnu.

Then Khamnu owned that he was her younger brother, and Thoibi was gracious to him and gave him of her sweetmeats, and then bade him go home lest the wrath of the King visit him, for he seemed goodly to her eyes. When Thoibi had returned to the Palace she bade Khamnu show her the place wherein she lived. So they went to Khamnu's house, and Thoibi saw that the gate was broken. But she sat on a red cloth near the post on the north side which men call ukoklel. Khamba hid himself in the far comer where there was a mat, for the house was old and full of holes, yet Thoibi said nothing in blame, but only that the house was nice. She asked what the mat in the corner was hung for, and Khamnu told her that there was their God Khumalpokpa (the ancestor of the Khumals). Then Thoibi said, " May I pray to him, for I seek a mercy of him ? " Then, so that Khamba might hear her words, she prayed aloud to the God to give her heart's desire to stay in the house and worship him daily. Then Khamba laughed aloud and both the women heard ; then Thoibi said, " Your God has spoken to me." She sat down in the veranda and Khamba came out and sent his sister to the village to bring some fruit. When she was gone, Thoibi bade her maid Senu go to Khamba bearing gifts to him, and say, " My Lord, my Lady bids me give you these, for she desires to be your servant, and to think of none other. To you will she give herself." So he took the gifts and they two bound themselves by a mighty oath before the God Khumalpokpa, and drank the water in which the golden brace- let was dipped, and each vowed love to the other.

Then Thoibi called Khamnu sister and bade Khamba go out among the folk and show himself to the King's officers. So Khamba went out and joined the young men who were learning to wrestle. An elder who stood by, saw the strength of Khamba and bade him wrestle, and he joined in wrestling, and at last the champion of the countryside invited him to wrestle, but Khamba was not thrown for all that the other knew many devices whereby he had often thrown great men. As it fell out, there passed by Nongthonba, the minister of the King, who stopped and asked the name of the young man whom the champion could not throw. With the great man ^^ were the servants who followed him, his clients and those that sought to win his favour.

Then he sent for the great champion and asked of him the name of the young man with whom he strove, " for indeed I know him, yet cannot I mind me of his name." " I know not," said the other, " yet verily is he a strong man, like a rock so hard is he to move, like the might of a river that cannot be stayed." Then he asked of Khamba his name and the name of his sire, and Khamba answering said, " Men call me Khamba, but my sire's name I know not." " What manner of man is this," said the King's minister in wrath, " that knows not the name of his sire ? " Then Khamba said, " My sire died when I was yet a babe, and my sister brought me to manhood. Peradventure she will know the name of my sire." Then the King's minister remembered the face of the lad, for it was even as the face of one who was his friend, and he was sorrowful, for he had spoken sharply to the lad in reproof. " True is it indeed that the elephant knows not his own brother, and kings forget their sons. Your father died ere his prime, even as a tree dies when men strip it of its bark." So he loved the lad, and in his delight went not to the King's Durbar, but to his house, where he told the women folk of the lad he had met, and bade them take fine clothes and an offering of dainties, for he was minded that his first-bom son should take Khamnu, the sister of Khamba, to wife even as he had promised to her father. So they went to Khamnu, who hid herself in the women's chamber, and they stood and wept outside, and lamented, so that Khamnu relented and spake with them, and took from their hands the apparel," a dress for the morning and a dress for the time when women gather at the bazar, and a dress for the great days when the Gods make merry. Then ere Khamba set forth on the morrow, Khamnu gave him sage counsel. " If any, jealous, puts a stick in thy path, walk not over it, but round it, for they are minded to do thee harm who are evil. Jostle not in the crowd, for they envy thee." So the lad went with the King's minister to the market-place, where the Jubraj sat, and the Minister, with a lowly obeisance, set Khamba before the Jubraj, and told of his sire and of his strength. Then they set him before the King, who was gracious unto him and spoke of his father, and bade them enrol him among his servants, and bade them also set the great wrestler Kongyamba among his servants, and when, according to the custom of the land, they had given largesse to the men of their village, the King bade them gather flowers for the service of the God Thangjing on the morrow.

Then they set forth to their homes, and Khamba told Khanmu all that had befallen him, and how he purposed to gather flowers for the service of the God on the morrow, and the Jubraj told his folk of the prowess and might of the son of his old friend, how the King had enrolled him, the son orphaned in his infancy, the child of a brave man, one who was wise in counsel, well versed in matters of state, and a leader of men in war, and made him his servant among them that bear office, for he was a man of high birth and a glory to his Panna. Then Thoibi said to her father, " In truth you should have honoured him yourself and built him an house, upon the north of your palace, and you should have given him food daily." So she went forth and told her mother that the festival of the Gods was at hand. But she went to see Khamba, and he told her how the King had made him Khunthak Leiroi Hanjaba and had bidden him gather flowers from the hills. " Great trouble is in store for you if you essay to gather flowers on the hills. Eather will I collect them in the village and in the bazar " ; and she cooked him food for the morrow and tied it in a bundle of leaves, fastening it with seven diflferent kinds of silk. On the morrow KSngyamba came for Khamba and chid him for being late, and, being the elder, bade Khamba carry his food. Ehamba was wroth thereat, and flung it on the ground. So they went on to a place where the flowers grew, and Kongyamba marked it with knots tied in the jungle ^* and claimed it as the place where his father was wont to gather flowers, and threatened Khamba with the wrath of the King. Then was Khamba wroth, and asked, " Where is the place where my father was wont to gather flowers ?" Kongyamba pointed to the hills yet south of where they stood, and thither Khamba went, but he found no flowers. So he prayed to the God Thangjing, and the God had compassion on his servant's distress, and sent a whirl- wind, upon whose wings was borne to the nostrils of Khamba a fragrance of many flowers. So Khamba went on and found a tree in a valley below whereon grew many flowers. He made obeisance to the God and did reverence to the tree ere he climbed it. So he gathered the flowers and threw them down, and by the grace of the God not a petal was broken. He sang on the way back the Khulang Isei, honouring the name of the Princess Thoibi, and Kongyamba heard it and questioned him, but Khamba said, " I sing of Toibi" ^* Then they quarrelled again and fought, because Kongyamba bade Khamba carry all the flowers and Khamba would not. Then they desisted and fell to eating, for it was late, and the odour of the savoury food which Thoibi had prepared for Khamba was very rich, and while Kong- yamba questioned Khamba about it, the crows came and ate the cakes which Kongyamba had brought for his refreshment. So he was wroth, and when he had returned home, he was enraged with his younger wife, and would not let her wash his feet. But when Khamba had returned home, Thoibi said, " Here is my lord and master," and washed his feet and gave him fruit to eat. Mean- while Kongyamba sent his men forth to question whence Khamba had got such dainty food, and they went to the Palace to ask of the Ningon Lakpa if there had been a feast, but they came back in sore haste, for Thoibi bade the porters drive them oflF. Then Kongyamba was minded to vex Khamba, so he gathered the village folk at the gateway of Khamba's house, ^^ and proclaimed to them all the King's orders, that on the morrow, the festival of the Gods, all should be clad in gay robes with jewels of gold and of silver. Then Khamnu came forth and asked him, " What sayest thou ? " And he answered her roughly, " Hast thou no ears ? Have I not proclaimed the will of the King all day long till my lungs are dry and my throat parched ? Go to." So she wept for shame, and Khamba wept too, for the thought that he had no bright garments to wear on the morrow. But in the night, as they slept, they dreamed that they saw their father and mother standing by them, and that they told them to go to the house of Thonglen, for there were stored their clothes of honour. So they arose, and even in the night went to the house of Thonglen. The men seized them as thieves, and haled them before Thonglen in the morning, but he knew them as the children of his old friend Purenba, and gave them rich clothes to wear and taught them the dance, and appointed men to follow Khamba and women to serve Khamnu. Also he sent men to build their house anew." Then Senu and Thoibi came to the house bearing gifts of raiment and jewellery for Khamnu and Khamba, but they were perplexed, for they knew not the' house, so well and truly had the men built it anew. And Thoibi was sore vexed when she saw Khanmu and Khamba in the verandah wearing rich clothes, for she feared that Khamba had married the daughter of some rich man. Then Feiroijamba, the son of Nongtholba, who was betrothed to Khamnu, joined them, and they went to the Pat, where they met the Princess Thoibi riding in a rich dooli. Then Kongyamba distributed the flowers among the great men, to the King first and then to the Queen, and then to the High officers of state. And Khamba, greatly fearing, asked counsel of the Maibi Hanbi, who first set flowers before the God Thangjing. Then Khamba presented flowers to the great ones, first to the King, then to the Queen, and then to the High officers of state. Eight pleased were they all with the flowers set before them by Khamba, and they gave him rare gifts, many times more than the customary presents which they had given to Kongyamba. Then the dancing began, and Kongyamba and his wives danced.

Then Khamba and Thoibi danced and sang before the God, and their party was great, and the people gathered together and shouted with joy as they danced, whirling together, till at last they knelt in salutation before the God. Then Kongyamba was wroth and spake bitter words, and on the morrow the folk began to practise for the lamchel * and the wrestling, and the officers of the Pannas were bidden to choose their champions. So they chose Khamba, for he ran steadily in long strides with his chest low, even as those run who run far. They set him before Nongbal, who ran with his head high, swiftly indeed, but for a short distance. Then they ordained that this year the race be long. So of the two parties, both of the wrestlers and of those who run, Khamba was the chief, while Kongyamba was chief of the other parties.^® The Leikeirakpas were bidden to watch the start, and all the night Kongyamba talked with his men how best they might hinder and overcome the party of Khamba for, said he, " Many are the races I have won, and heavy will be my disgrace if this year I am second to Khamba." And Khamnu feared for Khamba lest the Mends of the other should do him harm, for they were many. On the morrow Nongbal Kongyamba set forth early with his party, and one said to another, " It is evil for the land if a poor man win the race. It betokeneth scarcity more than the folk can bear. Let us say this among the people ere the race be run." So they hailed khamba when he arrived, and said, "Hast not heard that thou art not numbered among those that run? Thy name is not set in the list." And the people that stood by assented thereto, and Kongyamba said, " Of evil import is it that a poor man such as thou should run, for it betokeneth scarcity in the land more than the folk can bear." So Khamba believed and returned home very sorrowful at heart, and told his sister all that had been said to him. Then Khamnu bade him go to her father-in-law and tell him all.

Then Khamba met Leikeirakpa Nongtholba, who was vexed with him and passed him in scorn, but Khamba ran before him and bowed himself to the ground before him and told him all. Then they went before the King, and the King bade Khamba run if there was yet time. So Khamba and his brother-in-law Feiroijamba sped to the starting-place, and they saw the runners kneeling and the bundle of grass was yet hoisted* So they shouted, "We bear the Bing's order," but the people shouted so that the runners started, and Kdngyamba taunted Khamba, "Bun with me, he said, but Khamba answered, " Not yet my friend/' Then they entreated the Leikeirakpas, and Khamba went to the appointed place and there worshipped the Gods, and then he too shouted, and so swiftly he ran that he overtook Feiroijamba whose pony was startled and ran away. Then the people of Kongyamba were fain to stay him, but he dashed them aside. At last he caught up Kongyamba, who ran slowly, for he was tired. Then fifteen horsemen, the men from the villages of Kongyamba, tried to stay Khamba, and in his mind ThOnglen was aware of the evil things they did, and the tears came to his eyes and he started up and asked leave of the King to see what things they were doing to Khamba. Then Khadarakpa, the friend of Kong- yamba, and Nongtholba set forth together, and Thoibi gave them party a gift for the swiftest in the race. Then turn by turn the twain ran, first one then the other, gaining but a little, and the women cried out to them. Then Khamnu cried out, "Bun on, Khamba, for thy Father's honour," and Th5nglen shouted to him, " Here is the lion ® thy Father touched, leap up and break his horn," and Khamba saluted the King and leapt up seven cubits high and brake the horn of the lion. Then Kongyamba came up and in his turn greeted the King. Yet the King was more pleased with Khamba and gave him a gold embroidered coat, and the Queen gave him rich apparel, and the King^s ministers heaped gifts upon him. So in the wrestling Khamba was the champion, and he surpassed all in putting the stone and tossing the caber.^ Then he and his sister gave largesse of many cloths among the elders of the village.

Then Kongyamba bethought him how best he might work evil upon Khamba. But the Gods taught him no hint of evil devices in his dreams, and he despaired greatly. Then he built himself a hut, wherein he might consult a familiar spirit, but this availed him not. Then it fell out that one day he met women from Khumal fishing in the river of Moirang, and he questioned them* " Ye women of Khumal, why do ye fish ear, and show him this rope of silk."Then Khamba set forth to find the bulL At first he found him not among the reeds. Then he went to a low hill and saw the bull, and went towards him calling him to tease him. Then the bull ran at him, but Khamba bent aside a little and the people cried out, Art afraid ? but Khamba answered them, *' I fear not ; I seek a good stance." Then he stood on firm ground and caught the bull by the horns, and they swayed together as they strove for the mastery. Then Khamba rested on the neck of the buU, who carried him into the jungle. And Khamba spake his Father's name softly into the ear of the bull, and showed him the silken rope. Then the bull remembered the name of his Master and knew the rope, and himself tied it round his own neck. Then Khamba brought the bull to the "place where stood Khamnu and ThoibL Then KOngyamba joined him there and isaid, " Let me help pull the bull along," and caught the rope, but the bull would not move, and Kdngyamba said, Look, I have rescued Khamba. I share the reward. Khamba had fallen into a ditch." Then KOngyamba's friends shouted aloud, " Lo, he has rescued Khamba," and the Kings were sore troubled to know what was right, so they bade Kdngyamba fight the bull in an enclosure, but he was afraid cmd. climbed for safety into a machdn. Then Khamba fought the bull bravely ; he caught it by the tail suddenly, and then on a sudden let it go so tii&t it fell on its knees. Then he seized it by its neck. Then the Kings did honour to Khamba and gave him many gifts, rich jewellery and clothing, and the Khumal King said to the Moirang King, " My brother, childless am I, let this man be my man and live with me," but the Moirang King would not, and on the morrow Khamba killed the bull in honour of the God Thangjing. Then it was ordained that at this festival there should be the archery as was customary in honour of the God Thangjing, ^ and that Kongyamba should pick up the arrows shot by the King and Khamba should gather those shot by the Jubraj. It fell oufc that the Jubraj asked Thoibi to give him his coat of gold em- broidery, but she had given it to Khamba. On the morrow when the target was set, the Maibas ^ sang a charm over the arrows and the bow of the King, and the King tried the bow and then loosed the arrows from the string. Kongyamba stood there girt ready and ran to fetch the arrows which he gave back to the King. Then Khamba girded up his loins, and when the bow and arrows of the Jubraj had been charmed, the Jubraj shot and so swiftly ran Khamba to pick them, that his cloth was loosed, and the Jubraj saw and knew the gold embroidered coat below. Wroth, indeed, was he, and when Khamba bowed himself to give him the arrow, he would not take it and turned his face away from him. Then Kongyamba took the arrow from the hand of Khamba and gave it to the Jubraj, who was pleased with him and said, " My daughter Thoibi is thine to wive. In five days will I send thee the marriage gifts." Then Nongtholba asked the Jubraj,

- ' Wherefore art thou wroth with Khamba?" and the Jubraj said,

" I like him not; I will not see his face." Then said Nongtholba, " Is thy daughter a fruit or a flower thus to be given away as a trifle of no worth ? On the day when Khamba slew the bull, the King, thy brother, promised her in wedlock to Khamba, in token whereof I set seven notches upon the lintel of the kanglct^ for men to see and know." Then the Jubraj said, " That I know not, but what I have said, I have said.^ My daughter I give to Kongyamba." Then the King was vexed, and the Jubraj went to his house and bade his wives get ready the marriage gifts, "for in five days I will give my daughter Thoibi in marriage to Kong- yamba." Then, lest Khamnu and Khamba should give him gifts on the appointed day, he ordained that none should sell fruits but by his leave, and leave to buy gave he only unto Kongyamba, and to none other. But ELhamba set forth to the village where dwelt Kabui Salang Maiba.^ When he stood at the gate, the Nagas who kept watch and ward there, seized him and took his load straps from him, and haled him to the pakhan- val where sat the Maiba. Then Khamba said, " Wherefore have thy men seized me and taken my load straps from me ? I am come hither to see my Father's friend the Salang Maiba." Then the Maiba plied him with questions and knew that he was indeed the son of his old friend, and sent off men to gather fruit for him. Then he showed Khamba the spot whereon his Father had done great deeds of valour in battle against the Kabuis. The men brought in two weighty baskets of fruits, and the Maiba added thereto of his store gifts for Thoibi and Khamnu and Khamba.

Then Khamba took the fruit home and Thoibi set it ready in eleven dishes," and talked with the chief Eani, who promised to stand ready with ten of the queens and ten maids to receive the gifts. On the morrow Kongyamba brought his gifts, but Thoibi lay sick with a fever, for an evil spirit had chanced in her path. So the Jubraj sent Kongyamba away, saying, " I will send my daughter anon, for she lies sick of a fever." After a while Thoibi arose. Then the Jubraj himself ailed and lay him down to rest a while. Then Thoibi's maid Senu swept clean the northern portion of the verandah,*' the place that folk call mangsok^ that is set apart for the women, and threw the dust on the southern part that is called phamen, which is set apart for the men. Then she smeared the northern part with fresh mud. Then came the Banis and sat in their places, and Khamba's gifts were set before them and they par- took of them and gave of them to the people. And it chanced, even as Thoibi had planned, that her Father, the Jubraj, who meanwhile had risen and gone with the King to see the men shoot in honour of the God Thangjing, returned home parched with thirst and craving the juice of some acid fruit. He asked of the queens, his wives, " Have ye any acid fruit?" and they said, Lord, we have none," but Thoibi said, " Father, I have firuit in my basket," and she brake the fruit into a silver cup and gave the juice to her father to drink, who relished it and said, " What fruit are these?" Then said Thoibi, " Men call them did kao and mak kao and her father saw not the guile in her answer and again said, " These are strange names. Whence come they ? " Then said Thoibi, " Father, dost thou not know the fruit ? They are the fruit which Khamba, thy son-in-law, has set before thee on his marriage." At this the Jubraj waxed wroth and threw his silver huqa at his daughter. Then Thoibi fainted as if in a trance wrought upon her by the skyey influence of Laimaren and Panthoibi.* The Jubraj was greatly terrified thereat, and the women wailed over her. So he said to his daughter, ** Child, daughter, wife of Khamba, arise and go to thy husband's kin." Then Thoibi arose, and the Jubraj was wroth again. Then he sent men to summon Kongyamba, and to say to Khamha, " Come to thy Lord, the Jubraj, for he is minded to give thee gifts," Then Kongyamba gathered men together and met amba by the way, and said to him, " Art thou minded to 3 up Thoibi ? " and Khamba answered him and said, Jest with me, fori will not give her up." Then. they quarrelled fought, and Khamba threw the man upon the ground and lit upon his belly and pressed his throat, and was minded to him, but the men that stood by, the friends of Kongyamba, lagged him off and beat him and tore his clothes, and bound L so that he could not move. Then the Jubraj came up on his it elephant and bade the men beat him. Then they made L fast to the elephant with ropes, but the mahout who bound I, knew that Khamba was innocent, and so bound him that yet had space to breathe. Then they goaded the elephant, the God Thangjing stayed it so that it moved not. At last agyamba took a spear and pricked it so that it moved with the a. But it harmed not Khamba. Then the dawn broke and men said " Khamba is dead," and they loosed him from the )hant and moved him away. In the darkness of the night the Idess Panthoibi came in a dream to Thoibi and said, " Dost u not know that thy man is bound by thy father's orders to elephant and they have nearly killed him." Then Thoibi je and girt her petticoat close to her, taking with her a knife, t found Khamba still tied, and cut the cords that still bound L, and chafed his limbs so that the blood ran through them. jn Khamba came to and knew Thoibi, and bade her send for aimnu, and one went and fetched her. When she came, she )t for sorrow at the plight of her brother. Then Feiroijamba le and gave help. Then Nongtholba was very wroth for all J had done to Khamba, and bade his son tell it all to the rap. Then the slaves of Thonglen told their lord that amba was dead, for the men had bound him to the feet of elephant, and he was very wroth and went to the Chirap h all his men armed and girt ready. Then Feiroijamba told Chirap thrice how cruelly men had tried to kill Khamba, the Jubraj heeded not the complaint. Yet again Feiroijamba I them, and Nongtholba in his wrath said, " Who is this that ed to touch my son-in-law." Then said the Jubraj, " I bade m kill Khamba, and I believed him dead. Vexed am I that still lives and, therefore, am I not minded to hearken to this iplaint." Then said Nongtholba, " My Lord, hast thou the power of life and death ? " Then the Jubraj answered and said, " Such power have I." Then said Nongtholba, " As I live and while I hold mine office, none shall dare to kill my son-in-law. Upon me is the task of guarding this realm. My counsel lis ever before the King. Let us before my Lord the King." So they joined hands and went before their Lord the King, and the King was wroth with the Jubraj, for Thoibi had told him all that they had sought to do to her husband. And the Eang for- bade the Jubraj to come in, for he said, " Peradventure he seeks to drive me out, and is leagued with mine enemies the Angoms. When he has killed all my captains that are mighty in battle, then will he kill me also." Then Thonglen came to the palace with all his men armed and girt ready, and vowed that he would kill all those who had sought to kill Khamba ; but N6ngthdlba pacified him saying, Shall a man wrestle with that great elephant and not get hurt ? " So Thonglen laid his anger aside. The King sent his own leech to minister to the hurts of Khamba, and sent daily gifts of food and money. And in the Durbar he asked Nongtholba to give him counsel, and he punished all those who had laid violent hands on Khamba, and the Jubraj he set in prison, and bade him stay there till Khamba was well again. So Thoibi tended her husband and he was well again. So the King set the Jubraj free and hoped that he would bear no malice against Khamba. Yet the Jubraj called his wives and summoned Thoibi, but she was tending Khamba, Then he said, Better be childless than be the father of this evil girl. Sell her to Kubo and let me never see her more." And he would not relent for all that they entreated him. So he summoned Hanjaba, and bade him take the girl to Tamurakpa, and sell her and bring back the price in silver and gold. Hien Thobi told Khamba, and said, " Dear husband, for thy sake I go to Kubo at my father's bidding. Forget me not, for I will come back." At daybreak she did obeisance to her father and mother, and wept so that the cry of her lamentations was like the thunder, and her mother wept also and all the maids. Then she went to Hanjaba, who had the secret orders of her father to Tamurakpa. He took away all her jewellery, and set out with her. On the way she met Khamba, and he wept with her for the happy days that were gone, and the grief of their separation.

Then Khamba gave her a staff to lean on by the way, but Thoibi planted it by the road and bade it blossom forth with leaves if she kept her love true and chaste for Khamba, and she set a mark upon a stone by the roadside as a token. Then she reached Kubo, where Tamurakpa counted out her price in gold and silver into the hand of Hanjaba. But Tamurakpa had pity on her sorrow and bade her go in and be with his daughter Changning Kanbi. The evil women of Kubo whispered to Changning, and persuaded her to send Thoibi forth to catch fish and gather fuel.*® While she was busied with her task, she dreamed that Khamba was with her, doing even as she herself, but when she woke, she knew that it was but a dream. Then the God Thangjing took pity on her, and Tamurakpa bade the women weave each of them a cloth, for he heard them wrang- ling. Changning sought to reproach Thoibi, and said, " Wayward child thou art. Thou had'st the chance of marry- ing Kongyamba a goodly man, a scion of a famed race, stout and comely, yet thy love turned to Khamba." And Tamu- rakpa heard, and his anger was kindled against his daughter, and he was fain to strike her, but Thoibi stayed him. So they wove together, and in the night Changning tore holes with a porcupine quill in the cloth which Thoibi had woven,**^ for she was jealous. When Thoibi arose, she saw all that had been done, but she sat to and so skilfully mended all the holes that Tamurakpa preferred the cloth she had woven, and threw a^ide the cloth which his daughter had woven. Then, while she worked at the loom, a wind brought ashes far drifting upon the loom, and Thoibi knew that they had come from Moirang. Then she wept as she thought of her husband and her home, and the God softened the heart of her father, and he sent men to bring her home again. But he warned Kongyamba and bade him meet her by the way. So Thoibi did obeisance to the Kubo God, and thanked Tamurakpa courteously as she went back with the men her father had sent. And when she had come to the place where was the stone on which she had set a mark as a token, she worshipped it and put gold and silver on it ; and when she came to the place wherein she had planted the staff which Khamba gave her, she saw that it had blossomed forth with leaves. Then Kongyamba was near and bade his men see if Thoibi was coming, and they shouted, " Lo, the Princess is at hand/' Then Thoibi heard the shout and bade the slaves that Tamn- rakpa had sent with her as tribute to the King Go on and sit near if the man is Khamba, but far apart if he be Kongyamba She went on and feigned friendship with him, and sat on his red cloth, but placed a stick between them. Then she asked for fruit, and Kongyamba brought her fruit, but she would not eat for she feigned that she ailed after her sojourn in Kubo. Then she asked Kongyamba to let her ride on his pony while he rode in her dooli. And he was not loth. Then when she was near home she galloped off on tlie pony to Khamba's house, and he took her and they all wept for very joy. Then Kongyamba was sore vexed for the girl had tricked him, and his friends availed him not, and he sought to win the ICing's ministers to hearken to him, but Thonglen and Nongtholba sent men to guard Khamba and Thoibi, and on the morrow the matter wag set before the King in his Durbur, and he bade them settle the matter by the ordeal of the spear, but as he spake an old woman came forth and said. " My Lord King, there is a tiger in the jungle hard -by that we fear," and the KiDg said, " Let the tiger bear witness hereiiul Unto him that kills the tiger, will I give the Princess Thoibi"] So they summoned the hui rai and fenced round jungle, and] on the morrow the King and his ministers gathered there in machcns So many folk were gathered there that it seemed like a white cloth spread on the ground.

Then they twain did obeisance 1 before the King, who laid his behest upon them, and bade them slay the tiger, and he feared for them lest the tiger kill them* I So they went and sought the lair of the beast, and in it they found the body of a girl but newly killed. Then they found the tiger, and sought to spear it, but it turned the spears away as they threw them. Then the tiger sprang upon them and biti Kongj^amba so that he died, but Khamba wounded the beast,! and drove it off. Then he carried Kongyamba to the machan, wherein sat his father. And Thonglen taunted Khamba, ** What art afraid ? Thy father slew five tigers and thou fearest onel Go to, I will come and kill the beast' Then Khamba entered! the jungle once more and found the tiger crouching in a hollow half hidden by the jungle, but in fuU view of the machan of the King. As the tiger leapt upon Khamba, he speared it through

11. The technical names of the followers of a great man are : (a) Loin or lois who follow ; (6) Khamin or voluntary followers who serve a great man ; (c) Haija, persons who have some petition to make from hai to speak and ja or cha the suffix of humility ; (d) Chacha are of a similar class to the last-mentioned.

12. Acceptance by Khamnu of these gifts is equivalent to betrothal with Feiroi-jamba.

13. Each side has a varying degree of importance and the north is highly favoured.

14. Puns of this kind are much appreciated in Manipur. The aspirate is not very distinct.

15. The Ningon Lakpa is a Court official who had charge of the young ladies.

16.This is a common method of annoying a neighbour.

17.These were Lois, and the renovation of a house is no long matter.

18.Leikeirakpa, an official who looks after leikei or quarters of a village.

19.Superstitions of this kind are common in Manipur and Khamba readily believes it.

20.The bundle of grass is lowered as the signal to start.

21.The races are not fairly run as hustling is permitted.

22.Khadarakpa is the title of a Court official at M oirang.

23.The nungsha or lion here described is commonly held to be a Meithei emblem, but it is here associated with Royalty at Moirang.

24. The sports of Manipur are fully described above.

25. The hut was built of light lattice work, and the process of consulting a familiar spirit is technically and euphemistically known as hharai cliaiigha, literally to go into the latticed hut. The reason why a latticed hut is employed is to permit the spirit to enter and depart freely, which was denied to it in heavily-thatched houses or in pucca buildings. It ii clear that Kongyamba is recognized as having recourse to very shabby devices to defeat Khamba.

26.Each village has its recognized boundaries, and the jurisdictions of such tribal divisions as existed were also demarcated. It is worthy of note that the Moirang and the Kumal tribes each seems to have been associated with a definite locality.

27.Maibis are priestesses. See section above under "Priesthood,** p. 109.

28.The use of words of evil import in the presence of the King was a dire offence. It is comparable with the old idea that fighting a duel in the precincts of the Court at St. James* was treason and punishable as such.

29.The Kangla is the Royal Hall of Coronation.

30.The curious may parallel this episode in that very modern novel, ^* The Car of Destiny."

31.The ceremony u hai kappa (u = wood, kai = split, from khai, and kappa = to shoot ; it is just possible that kai = granary) has now been absorbed into the ritual of the Durga Puja, and takes place on the last day of the Puja. I am inclined to connect it with such a rite as that practised by the Kabuis, who place a straw image at the village gate and throw spears at it. The success or failure of the village lads affects tiie prosperity of the crops. The feature of the rite u kai kappa was that the swifteat runnenj gatliered the arrows aa they wore shot and brought them back.

32.The maibas are the miniatera of the ancient animiafc culta, and chami by their niagic the implements used on all these occaaions. The participation even to-day of a maiba in any religions ceremony is a sure proof that the ceremony is not Hindu in origin.

33. The exigencies of trarislation have revealed a curious anticipation of political oratory.

34. I do not know whafc were the exact relationships of the Salang Maiba, who aeenis to be a representative of Moirang in a Naga village.

35. The Pakhanval, or Bachelors Hall, is an institntion of very great importance in the HiH villages, and there is reason to believe that in early times it exiated in Manipur, The question of the social importance of this institution will be discussed in a later volume.

36. The odd number is lucky. Compare the rain puja among the Tangkhula where the number of persons taking part is eleven also.

37.Each part of the house has its proper designation.

38.Mangsok the name of the part reserved for the women, is derived from mang — to pollute and sok = to touch. phameu — pham to sit.

39. cha kao = cha, child and kao, to forget ;mak kao = mak son-in-law and kao to forget. We may compnre lukhra pakhra widows and widowers, the name given to *'speargrass " by the Manipuris.

40. The Jubraj had partaken of Khamba'a gifts, and would be held to have recognized him .

41.Laimaren and Panthoibi are deities of Pre Hindu days

42. This is formal recognition of the tie which had been created between the two. It is thus clear that there are two things essential for marriage according to the incidents of this story. The first is cohabitation, and the second is the exchange of gifts. In the scene in the house of Khamba when Thoibi worships the Khtimal God in the conier, they are represented as cohabiting. Cf. note 12 above.

43. This curious association of the Angoma with treasonable practices is notably exemplified by instances in Manipur history, where the Angom Ningthou was often the head and centre of disaffection and rebellion. The Angom Ningthou is almost always closely associated by marriage with the Meithei Ningthou,

44.Tamurakpa is the lakpa appointed to reside at Tamu in the Kubo valley and act as agent there.

45. The story of the staff that puts forth leaves in proof of the chastity of the woman who plants it is well known.

46.Thoibi is set to these menial tasks in order to humiliate her. The women of Kubo are not held in very great esteem by the Manipuris.

47.Compare Penelope's web.

48.Persons holding office are entitled to have a red cloth carried before them on which they sit. Cf. p. 13, supra.

49 When the man desires to keep separate from the woman whom he has married, he may phwse a sword or spear between them. This custom, which is described in Emnanitif Vol. 36, No. 141^ pp. 36, aey., 1907» is connected with the tabu prohibiting intercourse between waniors and their wives. This incident here is of importance, as the barrier is raised by the woman whose weapon ia the stick, ptiasibly the lineal descendant of the digging-Htick. By doing this Thoibi keeps EOngyamba at a distance.

50.The hui rai are the trackers and scouts. Hut = dog and rat = to own. See section on hunting,

51. This is the usual signal to call a woman from her house. The mat wall is not damaged, and the lady within knows what is meant.

52. It is commonly believed that both Khamba and Thoibi were of giant size. This belief is not borne out by the clothes said to have belonged to them which are shown still at the shrine of Thangjing near Moirang. I have seen them, and while they do not in genend differ from the present costume, the patterns of the embroidery is not modem.

53. The translation which I possess omits several comic interludes in which Nongtholba plays an important part. The interludes tend to increase in number, and the recitation of the ballad occupies two days at least. The pictures which illustrate it are by Bhudro Sing, a native Manipuri artist, who, if my recollection serves me aright, painted them while in jail undergoing a spell of imprisonment. satisfactorily proved. So also with regard to the Naga group; while of the relations of Meithei to the Eachin group, Dr. Grierson remarks that the two are closely connected, and that Meithei must be considered as the link between Eachin and the kuki-Chin groups. Of its relationship to the numerous dialects composing the kuki-Chin group, Dr. Grierson states that it must be held to be an independent member of the group with points of agreement, not only with the northern dialects but with the southern members as well, though differing from all in many essential points.

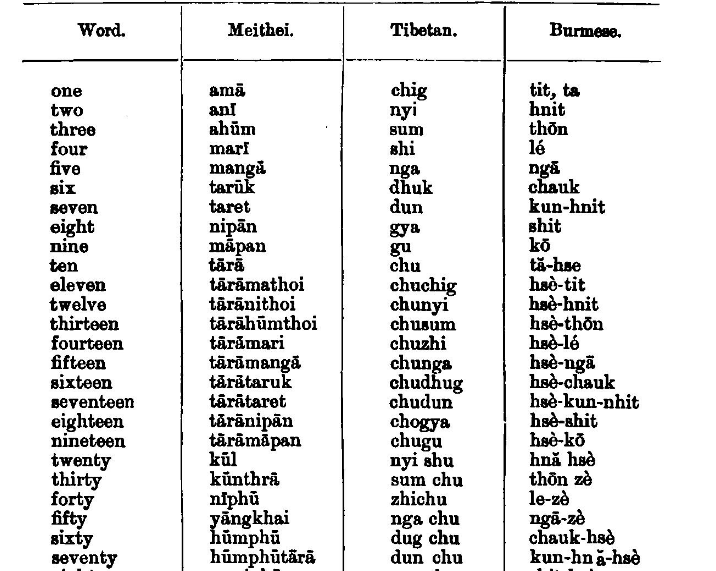

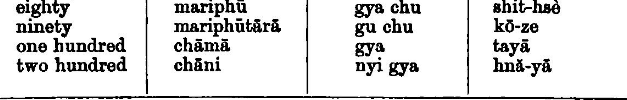

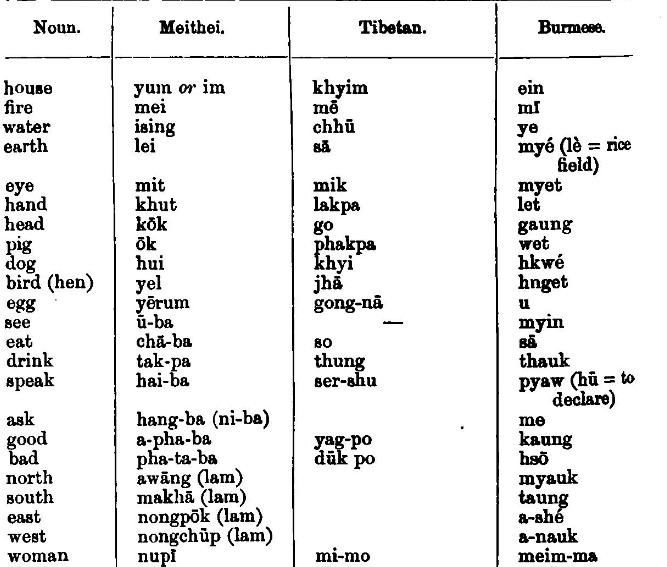

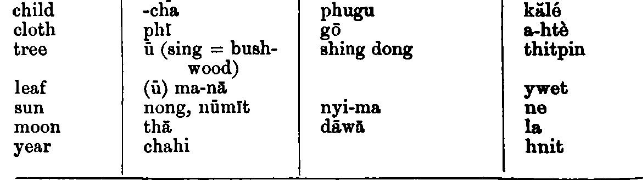

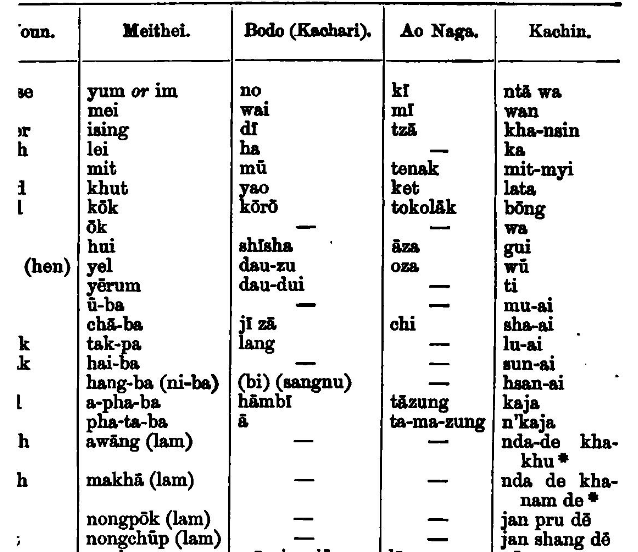

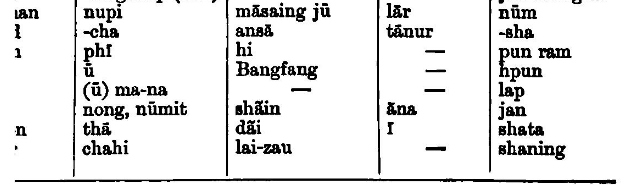

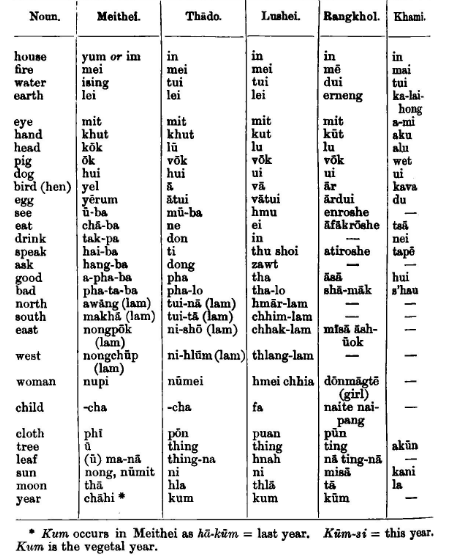

To make these conclusions more clear it will be useful to employ a scheme of comparison by which these facts will be exhibited. I propose firstly, to compare the structure of Meithei in the following points, (a) numerals, (b) negatives, (c) plurals, (d) relatives, (e) order of words, with the corresponding points in Tibetan and Burmese, then with the same points in Eachari (Bodo), in a typical Naga dialect such as Ao Naga, in Eachin in the next place, and lastly, with the same points in Thado as representing the northern Chin sub-group, in Lushei as typical of the Central Chin sub-group, in Sangkhol as belonging to the Old Euki sub-group, and in Ehami as the representative of the Southern Chin sub-group. The same method of comparison will be employed in order to show similarities of vocabulary, although the comparison must be limited to a small number of elementary words. It would have been impossible to attempt this scheme without the com- parative tables in the Linguistic Survey Report.*

To the kindness of Mr. J. E. Bridges, Eeader of Burmese at the University of London, University College, I owe the notes on Burmese and the lists of Burmese words which appear below.

In the sketch of the grammar of Meithei which follows, no mention is made of irregularities and unusual forms, which are numerous enough and which will be dealt with at length in a separate volume.

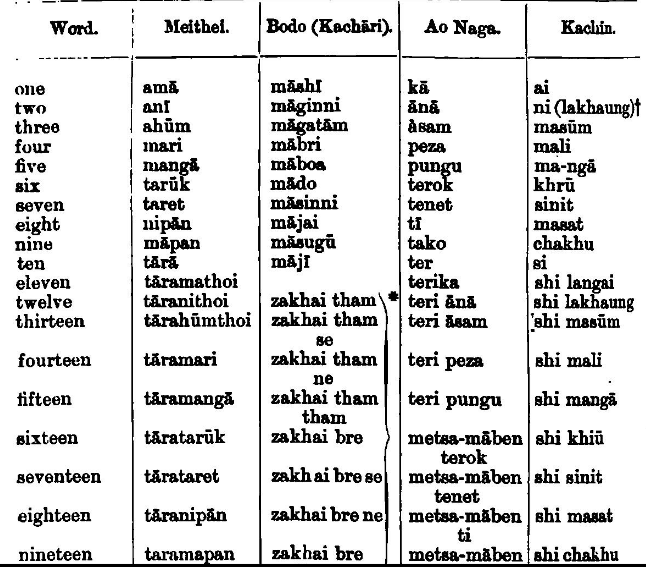

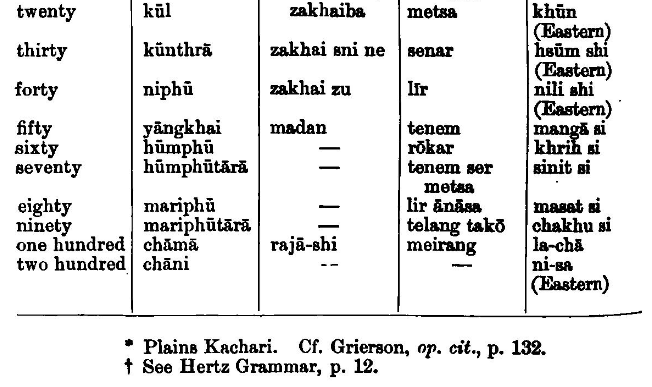

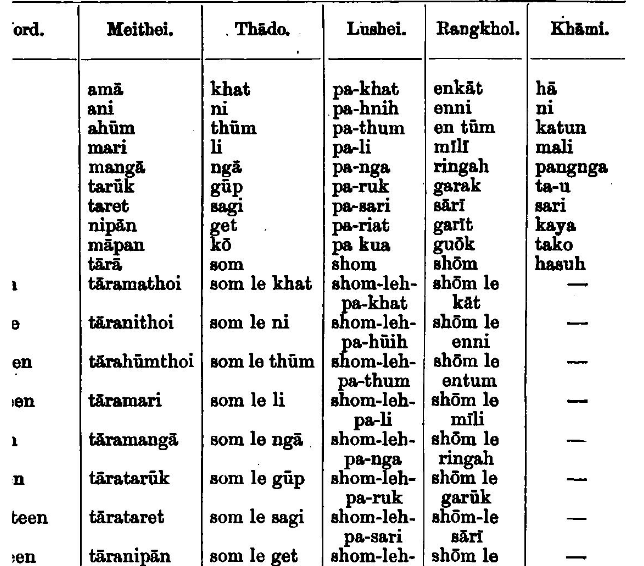

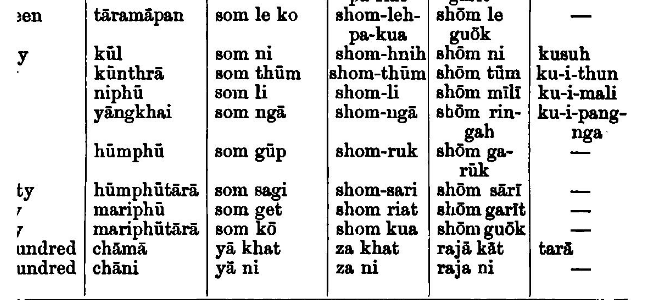

Meithei Numerals

Of the simple numerals, those for eight and nine require special mention. Nipdn and mapan seem to mean two '* ofif " and one " ofif " respectively. Something not un- like this is found among the higher numerals in Ao Naga and Angami Naga.* The addition of what seems to be an otiose syllable thM to the numerals, eleven, twelve, thirteen is notable. Kul = twenty, is paralleled by the Eastern Kachin word Khun. Kunthra = kUti tara. It is possible to equate the Meithei tdra = ten with the Ao Naga ter. In Meithei the higher numbers above forty are formed by multiplying in scores, the multiplier being prefixed to the word phu = score. Fifty (yangkhai) may be resolved into ydng t = chd = one hundred, and khai = to divide, to half, cf. makhai = half. Sixty is three score. Seventy = three score plus ten. It will be noticed that the multiplier precedes and the addendum follows. In multiplying hundreds the multiplier follows the word (chd) for hundred.

Tibetan Numerals

The Tibetan system of numerals follows a constant rule. The multiplier precedes while the addendum follows the theme, which is by decimals. Thus five hundred and ninety-two would be five hundreds, nine tens, two.

Burmese Numerals

The Burmese system resembles the Tibetan, and is based on tens, not on scores, as in Meithei.

Kachari Numurals

Here we have a very curious system based on " fours." Thus we have zakhai zu = 40. Zakhai = four and zu = ten. For numbers intermediate between exact multiplication we have the rule that the multiplier immediately follows the "four," while the addendum come next. Thus zakhai tham tham = 4 X 3 + 3 = 15. This method carries us only up to 40, and is only used by the " Plains Kacharis."

Ao Naga Numerals

Reference has been made to the mean- ing of the numerals 16, 17, 18, 19, in this language. || The forms for six, seven and ten, resemble those in Meithei. The higher numerals are formed on distinct lines. The forms for 30, 40, 50 and 60 are, so far as I can see, not "multiplied numerals."

The form for 70 is aaalysable into 50 + 20 : that for 80 = twice 40. I cannot solve the mystery of telang tako = 90, for telang = 100, while tako = nine.*

Kachin Numerals

Mention has been made of the similarity between the Meithei kul = 20, and Kachin khun = 20. The higher numerals are formed by tens, the multiplier preceding the ten.

Thado Numerals

The formation proceeds by tens through- out, the multiplier following the ten and the addendum bring marked by the conjunction le

Lushei Numerals

The Lushei system resembles that of the Thados as above described.§

Rangkhol Numerals

It is interesting to observe that Rang- khol, which forms its higher numerals as Lushei and Thado,haS the syllable ruk in its word for six, like Meithei and Lushei, but not Thado.

Khami Numerals

So far as my materials go, it seems that the higher numerals follow the use of Thado, Lushei and Eangkhol in suffixing the multiplier.

It will be seen that up to one hundred the Meithei numerals show points of likeness to Tibetan numerals, where the multi- plier precedes, and in the formation of '* hundreds " follows the Kuki-Chin system where the multiplier follows the multi- plicand. Resemblances of form as well as of formation are as widely and as strangely distributed.

Plurals

In Meithei the plural sign is often omitted. Where the fact of plurality is to be emphasized, the suffix sing is added to nouns denoting human beings, as nupi sing = the women. The same emphasis is obtained by using words as yam, which means many, as ml-yam = a crowd of men.

In Tibetan the plural sign is often omitted, when, from oircumstances, the fact of plurality is clear ; but such words as

- all," " many," and numerals, are used as plural affixes in addition

lao the usual affixes nam and dag,"*