The Nobel Prize and India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

From: Oct 15, 2019: The Times of India

From: Oct 15, 2019: The Times of India

See graphics:

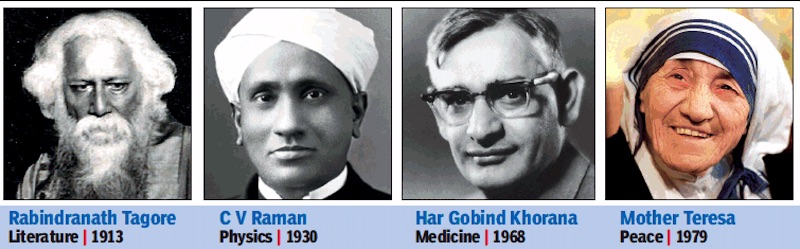

Indians and the Nobel Prize, 1913-1979

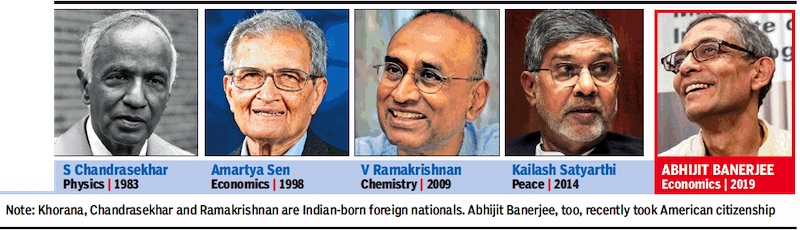

Indians and the Nobel Prize, 1983-2019

The complete list

1902 Ronald Ross, Medicine (Ross was a British national born in Almora, India, and whose work was entirely India-oriented)

1907 Rudyard Kipling, Literature. (Kipling was a British national born in Bombay, India. His work was entirely India-oriented)

1913 Rabindranath Tagore, the author of "Gitanjali" became the first non European to win the Nobel prize for Literature.

1930 Chandrasekhara Venkata Raman an Indian Physicist who was awarded the Nobel prize for Physics.

1968 Har Gobind Khorana , an Indian American biochemist was awarded the Nobel prize for medicine.

1979 St. Teresa of Calcutta was awarded the Nobel peace prize. She was a Roman Catholic missionary and an Indian citizen of Albanian origin who lived for most of her life in India.

1983 Subramanyan Chandrasekhar, an Indian American astrophysicist was awarded the Nobel prize in Physics.

1998 Amartya Sen , a professor of economics and philosophy at Harvard University, received the Nobel prize for economics.

2009 Venkatraman Ramakrishnan was awarded the Nobel prize in Chemistry

2014 Kailash Satyarthi, Indian child rights activist, along with Pakistani child rights activist Malala Yousafzai, was jointly awarded the Nobel peace prize in 2014. Satyarthi gave up his career as an electrical engineer over three decades ago to start Bachpan Bachao Andolan, or Save the Childhood Movement.

2014 Abhijit Banerjee

Nominations

The Times of India Oct 09 2014

Between 1901 and 2014, the prize has been awarded 561 times, of which only seven were won by Indian citizens. However, between 1901 and 1963, the years for which nomination data is available, 123 Indians were nominated for the prize.

The Times of India

S Radhakrishnan got 15 nominations, the highest for any Indian during this period. Nominations are by a select group of people, including members of the respective Nobel committees, Nobel laureates and so on. The statutes of the Nobel Foundation restrict disclosure of information about nominations for 50 years and hence 1963 is the present cut-off year.

The 123 nominations from India include a few Britishers (excluding Ronald Ross and Rudyard Kipling) working in India at the time of nomination.

Source: nobelprize.org Research: Atul Thakur

Nobel shortlisted literature

Anil Nair

The Times of India, Oct 9, 2011

The Swedish Academy, notoriously rule-bound, created a minor kerfuffle by announcing what appeared initially to be the first posthumous award in Nobel history – it nominated Ralph Steinman for the medicine prize, unaware that the physician had passed away three days ago. Two days later, Indian stargazers experienced a unique frisson when the online bookmaker Ladbrokes reported a 25/1 odds on Malayalam poet and critic K Sachidanandan getting the literature Nobel. He shared the same odds with perennial Nobel hopefuls such as Philip Roth and Don DeLillo. There was one more Indian in the reckoning this year – Rajasthani writer Vijaydan Detha. Indians from Kamala Das to Mahashweta Devi have featured on the unofficial Nobel shortlist. But almost 100 years after Rabindranath Tagore became the first and only Indian to actually bag it, the 2011 list seemed to infuse some substance into what has largely been a chimera.

Sachidanandan’s own reaction, when he first heard his name in the shortlist, veered from disbelief to jubilation to quiet pride. “There is need for better English translations of those who write in Indian languages. It is this dearth which accounts for our lack of visibility at the highest level,” Sachidanandan said. A prolific translator himself, he introduced Malayalam readers to the poems of Tomas Transtromer, the winner of the Nobel this year, and with whom he recited poetry as a gesture of protest outside the sealed Union Carbide premises soon after the Bhopal gas tragedy.

Sachidanandan feels that Indian bhasha (vernacular) writers match the best in the world, a contention that raises the ghosts of Salman Rushdie’s irascible remarks in the late ’90s, echoed with equal vehemence by V S Naipaul later, that Indian literature minus Indo-Anglian writing amounted to mere sentimentalism and superstition. There have been various ripostes to this, but few rival writer Amit Chaudhuri’s in wit and perception when he described Rushdie as “a kind of hallucinatory cliff behind which we cannot see, almost like an obstruction we’ve created.”

The Nobel is awarded only for living writers, but the deciding coterie’s sense of timing has always been disputed. Having scandalously excluded Joyce, Proust and Nabokov, those casually ignored who will never get a second chance would include Indians like Sadaat Hasan Manto, R K Narayan, U R Ananthamurthy and O V Vijayan. Narayan wrote in English, which makes him technically an Indo-Anglian, writer but he is closer to a Kannada sensibility, which as Chaudhuri shows, “cannot and doesn't want to speak on behalf of something called India or pretend to be Indian literature” than to Rusdhie’s chutnified prose.

This is even more so in the case of writers like Manto, Vijayan, and, to bring in a contemporary, Mahashweta Devi. “Some of our best writers like Mahashweta Devi have been able to remain rooted to their milieu while invoking universal concerns, and therein lies their strength,” says Sarah Joseph, a Malayalam writer well-known for her non-conformist themes and shimmering prose. It is possible that English translations have failed to do sufficient justice to a Manto or a Sunil Gangopadhyay. But that could have hardly been the case with Vijayan, who translated his own Malayalam works into English, and whose border crossings between the two languages resembled, as poet Jayanta Mahapatra said, “the descent into a mine with a caged canary in hand”.

Indian-born British resident Chaudhuri sums it well when he says, “[It is about] the role of English in India and the role of India itself in the globalized world. But the idea of linking literature to the economic fate of a nation is to miss precisely the ironical force of literature.