Water: Drinking water, rural water and its availability, India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. the Facebook community, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be acknowledged in your name. |

Contents |

Atal Bhujal Yojana

Uttar Pradesh

2017-21

Neha Lalchandani, Oct 6, 2021: The Times of India

From: Neha Lalchandani, Oct 6, 2021: The Times of India

Ensuring piped water supply to as many blocks as possible and improvement in irrigation schemes have helped in stabilising groundwater levels in as many as 35 districts of Uttar Pradesh since 2017.

The centrally-funded Atal Bhujal Yojana was initially implemented in water-stressed areas of seven states, including 10 districts of Uttar Pradesh. These included 26 blocks and 550 gram panchayats in Mahoba, Jhansi, Banda, Hamirpur, Chitrakoot, Lalitpur, Muzaffarnagar, Shamli, Baghpat and Meerut districts.

Satisfied with the impact of the scheme in these districts, the state government decided to extend the scheme to the remaining 65 districts.

From April 1 this year, all 826 blocks in the state are being covered under the scheme for improvement in groundwater levels. The scheme will run till 2026 under which the government will focus on developing a water security plan, followed by work in the 75 over-exploited blocks in the second year, critical blocks in the third and semi-critical blocks in the fourth year.

Principal secretary, Namami Gange, Anurag Srivastava, said, “Improvement in groundwater levels is the result of a multi-focus approach by the government. Due to this, around 82 blocks that were either critical or overexploited have seen an improvement.”

“Conservation efforts like afforestation on a large scale, rehabilitation of village ponds through MNREGA and state funds, and construction of check dams have shown a massive improvement. Another major step taken by the government was to ban new borings by industrial units in overexploited areas. As soon as excessive withdrawal of water from the ground stopped, the resources were replenished,” he said.

“The new law requires applications to be made on a specified portal and the rejection rate is about 30-35%,” Srivastava said, asserting that there was absolute transparency in renewal of licences for industrial extraction of groundwater.

Meanwhile, UP has also secured top position in the implementation of Atal Bhujal Yojana. Under the centrally-sponsored scheme, the government initiated groundwater conservation measures, conducted awareness programmes and made interventions on the demand and supply side. This also included geotagging of ponds and check dams which are maintained by the government.

A government spokesperson said groundwater exploitation had intensified with the spread of hand pumps across the state. “Even now, while piped water is being provided to districts where supply is low, around 27 lakh hand pumps are in operation in UP,” he added.

“UP has a large area where groundwater is available in abundance, easily accessible and of good quality. But there are some regions which face issues related to the quality of groundwater, especially the presence of arsenic and fluoride. Bundelkhand and Vindhya regions have hilly terrain where the availability of groundwater is neither good nor perennial. This is the reason why the Har Ghar Nal Scheme started with this region,” he said.

The Water Crisis: The essential facts

John Hawthorne's analysis/ 2018

When contemplating our world’s most precious resources, past conversations often centered around fossil fuels and the consequences once those become scarce.

However, recent times have given us an abundance of alternative energy options and new technologies either in use or on the horizon. These innovations have turned the conversation to a resource that, on a basic level, is readily abundant and covers two-thirds of the earth’s surface.

Water.

More specifically, freshwater.

Though 70% of the earth is covered in water, only 2% of it is fresh. Further complicating the issue is that 1.6% of that freshwater is contained in glaciers and polar ice caps.

Many third world and developing countries struggle with ensuring this basic tenant of our existence is both available and safe. Nowhere is this more apparent than India.

A Major Lack of Resources

With the planets second largest population at 1.3 billion, and expectant growth to 1.7 billion by 2050, India finds itself unable to serve the vast majority of that populace with safe, clean water.

Supporting 16% of the world’s inhabitants is daunting enough, but it is even more so when recognizing that population is crammed into an area one-third the size of the United States. Then consider that India only possesses 4% of the world’s fresh water and the crisis can be more fully realized.

India may not be the only nation in this predicament, but theirs is at a stage more critical than most. Severe lack of regulation, over privatization, general neglect and rampant government corruption have led to multiple generations thirsting for more than just a few drops of hazard free water.

The situation has grown to the point that regional disputes have risen over access to rivers in the country’s interior. Those disputes take on a global scale in conflicts with Pakistan over the River Indus and River Sutley in the west and north and with China to the east with the River Brahmaputra.

Surface water isn’t the only source reaching a breaking point.

Tracing back several generations, the critical situation in India can be linked to a myriad of causes. In modern times though, the concern has moved from the surface to the ground. And it’s there where India’s freshwater is under the greatest stress.

Causes: Groundwater and A History of Indifference

Over the past 50 years, policies have allowed what amounts to a free-for-all in groundwater development and as the crisis has grown it has been met with continued neglect, mismanagement and overall indifference.

Estimates put India’s groundwater use at roughly one-quarter of the global usage with total usage surpassing that of China and the United States combined. With farmers provided electricity subsidies to help power the groundwater pumping, the water table has seen a drop of up to 4 meters in some parts of the country. This unfettered draining of groundwater sources has accelerated over the past two decades.

With the aggressive pumping, particularly in rural areas, where agriculture provides the livelihood for upwards of 600 million Indians, Mother Nature is often the difference in a good year and a devastating one. Relying on monsoon rains without proper irrigation or water management techniques has been a recipe for disaster.

Mismanagement and corruption often draw the largest headlines, but many of India’s leaders have also been slow or unwilling to adapt to newer technologies or cohesive plans to address the issues.

The response can at best be described as irresponsible. Consider China, a country with roughly 50 million more people, uses a quarter less freshwater.

Growing Demand, Declining Health

Not only is India the world’s second most populated country, but it has a fast growing middle class that is raising the demands on clean, safe water. Then consider close to half of the country practises open defecation and you have a dichotomy of two very different populations desperately pulling at the same limited resource.

One group wanting to grow and flourish and the other wanting to survive.

A few numbers from the World Bank highlight the plight the country is facing:

- 163 Million Indians lack access to safe drinking water

- 210 Million Indians lack access to improved sanitation

- 21% of communicable diseases are linked to unsafe water

- 500 children under the age of five die from diarrhea each day in India

More than half of the rivers in India are highly polluted with numerous others at levels considered unsafe by modern standards. The waters of the Yamuna, Ganga and Sabarmati flow the dirtiest with a deadly mix of pollutants both hazardous and organic.

Aside from commonplace industrial pollution and waste, India’s rivers are open use across much of the country. From dumping human waste as previously noted to bathing to washing clothes, the human element contributes to the epidemic of health related concerns.

Adding to the human toll is the reliance on seasonal rains, which are often sporadic in some years and over abundant in others. Rain totals can vary greatly and do not always arrive in the places they are needed most. The drought and flooding that results from this inconsistent cycle often leads to crop failures and farmer suicides.

Much of the above affects rural citizens where poverty is rampant, but even more developed urban areas face their own challenges.

Even with a robustly growing middle class, when combining rural and urban populations, over half of India still lives at or below the poverty level. Furthermore, no city in India can provide clean, consumable tap water full-time.

Should the crisis continue unabated, the scarcity of water will have a negative impact on the industrial health of the country.

Recent drops in manufacturing jobs can be tied to companies being unable to access clean water. Along with the inability to properly cultivate agriculture areas and the water crisis quickly becomes an economic one.

Look to the Future

It may seem a foregone conclusion that the water will soon enough dry up and along with it India as a whole. That need not be the case.

There are even bright spots in the current environment. The Rivers Narmada and Chamabal run clean with water fit for consumption. Several projects are currently underway that aim to move water to areas that need it the most.

But it will take a long-term commitment of the Indian government not previously shown and the heavy assistance of outside resources.

Common sense practices and training will also aid in reducing the damage done to groundwater sources. Teaching farmers updated irrigation techniques, such as drip irrigation, and utilizing more rainwater harvesting are small, effective steps in stemming the loss of freshwater sources.

Much of India will also need modern sanitation policies that both conserve and wisely utilize water sources. Recognizing physical and economic growth directly ties to the amount of safe, usable water is another step in right direction.

Conclusion

Yes, all of these changes take the long view, but a crisis of this magnitude will not be solved with lip service and short sided solutions.

However daunting, the goals are not unattainable. India is still a developing society, and there is time to reverse the crisis that has been decades in the making.

Given the right commitment and dedication, India can soon enough have safe, clean water.

As assessed in 2021-22

Vishwa Mohan, March 22, 2023: The Times of India

From: Vishwa Mohan, March 22, 2023: The Times of India

On Independence Day in 2019, PM Modi set the goal to provide tap water to every rural household by 2024, and the country has made tremendous progress on this since. Over 11. 4 crore of India’s 19. 4 crore rural households (59%) have been covered already, so the promise will likely be fulfilled by next year. The big question, however, is whether all households will regularly get enough water of the right quality.

Given the precarious condition of its groundand surface-water resources (rivers, streams, lakes, wetlands and reservoirs), India could be a water-scarce country in the next 40 years.

With 1,486 cubic metres (1. 5 million litres) of water available per person, per annum, India falls in the water-stressed category. A dip below 1,000 cubic metres per person, per annum, will push it into the water-scarce category.

The manner of water consumption also compounds the problem. Central Ground Water Board (CGWB) statistics show the indiscriminate use of groundwater turned 4% (260) of the total 7,089 assessed units in the country critical in 2022 while 14% (1,006 units) were assessed as over-exploited. The situation was worse in 2017 when 17% of the units were over-exploited. Various recharge and conservation efforts have borne fruit but the number of such units remains high in states like Punjab, Rajasthan, Haryana, Delhi, Tamil Nadu and Karnataka.

Rivers And Lakes At Risk

In India, 87% of groundwater is extracted for irrigation and experts say excess withdrawal round the year may be the biggest reason for depletion, as the recharge primarily happens in the monsoon. On the other hand, encroachment of waterbodies and the discharge of untreated wastewater into rivers and streams have reduced the surface water resources.

“Pollution compromises the water and river bed soil quality, which adversely affects the biota (life forms) in it, and developmental projects play havoc with the river as a system, changing its pattern of flow, extent of floodplains, and its propensity to freely meander and erode and deposit silt on its banks,” said Manoj Misra, a retired Indian Forest Service officer who is an expert on water issues and convener of the not-for-profit ‘Yamuna Jiye Abhiyaan’ (Living Yamuna Campaign).

Misra added that the harm to rivers endangers the habitat conditions for aquatic and riparian biota (both plants and animals) and impacts rivers’ ability to recharge groundwater “affecting the nation’s water security”.

Mindless development takes a toll on river beds, ponds, tanks, lakes, etc. Statistics show 1. 6% (38,496) of India’s 24. 2 lakh waterbodies have already been encroached while 53,396 of them in rural areas are not in use as they have dried up, silted or turned saline, increasing the use of groundwater.

“Encroachment due to development projects, which alters the system in a far more fundamental manner, is often ignored or seen more as a mitigational challenge, which is a reflection of the poor understanding of rivers as an ecosystem by planners and engineers,” said Misra.

Groundwater Quality Falling

The country practically depends on groundwater, which meets 62% of India’s irrigation needs, 85% of rural water supply and 50% of urban water supply. So, it must be used judiciously and protected from contamination. While it is an annually replenishable resource, its availability varies from place to place and time to time with monsoon intensity.

Various reports show contamination of groundwater is one of the key challenges in achieving the target of universal tap-water supply under the government’s ‘Jal Jeevan Mission’ (JJM) by next year.

In December last year, 25,691 habitations were affected by one or more contaminants. More than half of them (13,716) had high (beyond acceptable limit) presence of iron, while 9,938 had salinity. Also, 760 habitations were affected by arsenic, 655 by fluoride, 515 by nitrate and 107 by heavy metals.

Eklavya Prasad, founder of the non-profit Megh Pyne Abhiyan that works on groundwater management issues in eastern India, said high levels of salinity, fluoride, nitrate, iron, arsenic, uranium, and some toxic metal ions had been observed over large areas, making groundwater hazardous.

Prasad said the over-exploitation of groundwater is threatening agriculture, drinking water availability, industry, and even water-based cultural practices. “The prevailing perception about groundwater largely portrays it as an infinite and safe resource, which is far from the reality,” he added, blaming ignorance among users and the government. “The paucity of knowledge about the quality and quantity of water has significantly contributed towards excessive abstraction of groundwater. ”To overcome this ignorance, Prasad recommended the creation of a “credible, localised, dynamic information system of groundwater across all rural and urban habitation units. Users have to be made aware about the quality of water and its quantity… to transform their perspective”.

Aquifer Mapping On

That is why the CGWB is implementing the National Aquifer Mapping Programme (NAQUIM) with an aim to identify the groundwater aquifer (water-bearing stratum of permeable rock or sand) systems along with their characterisation for sustainable management. Out of India’s total mappable area of nearly 25 lakh sq km, nearly 24. 6 lakh sq km had been covered by December 30, 2022. The rest is expected to be covered this month. The map will help states make their respective management plans, knowing the aquifer-wise availability of water and its potential. Rajasthan has the largest targeted area (3. 3 lakh sq km) for coverage under aquifer mapping, followed by Madhya Pradesh (2. 7 lakh sq km), Maharashtra (2. 6 lakh sq km), Uttar Pradesh (2. 4 lakh sq km) and Karnataka (1. 9 lakh sq km). Targeted areas had already been mapped in Rajasthan, Bihar (90,567 sq km), Jharkhand (76,705 sq km), Haryana (44,179sq km), Kerala (28,088 sq km), Uttarakhand (11,430 sq km), Himachal Pradesh (8,020 sq km), Goa (3,702 sq km), Jammu & Kashmir (9,506 sq km) and Delhi (1,483 sq km), among others, by December 2022.

The government has also taken up other interventions to conserve both rainwater and groundwater. One of them is Jal Shakti Abhiyan (JSA) that was launched in 2019 in the water-stressed blocks of 256 districts to harvest monsoon rainfall through artificial recharge structures, watershed management, recharge and reuse structures, intensive afforestation and awareness generation.

Atal Bhujal Yojana, implemented in certain water-stressed areas of Gujarat, Haryana, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh, in collaboration with the states, is another such scheme. It aims at sustainable groundwater management by involving the village communities in the targeted areas. Besides, last April the government undertook to rejuvenate waterbodies under the Amrit Sarovar Mission that aims to develop and rejuvenate 75 waterbodies in each district as part of independent India’s 75th anniversary celebrations. All these measures will, however, help only if the states stop encroachment of their existing waterbodies through judicious development.

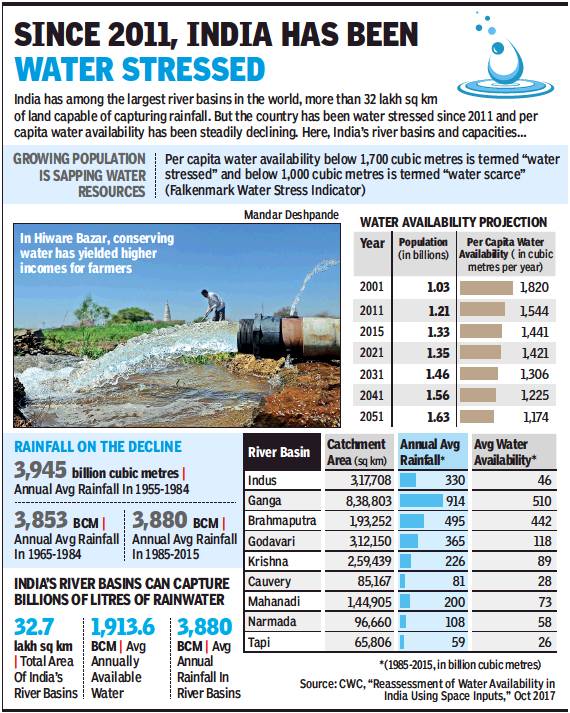

Water crisis in India

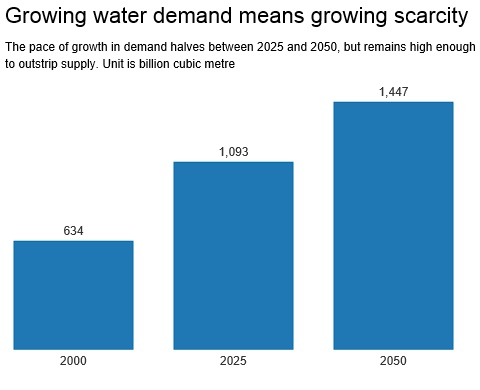

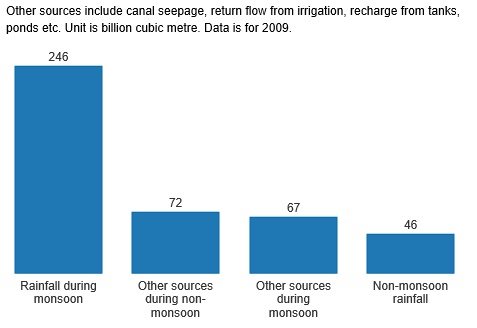

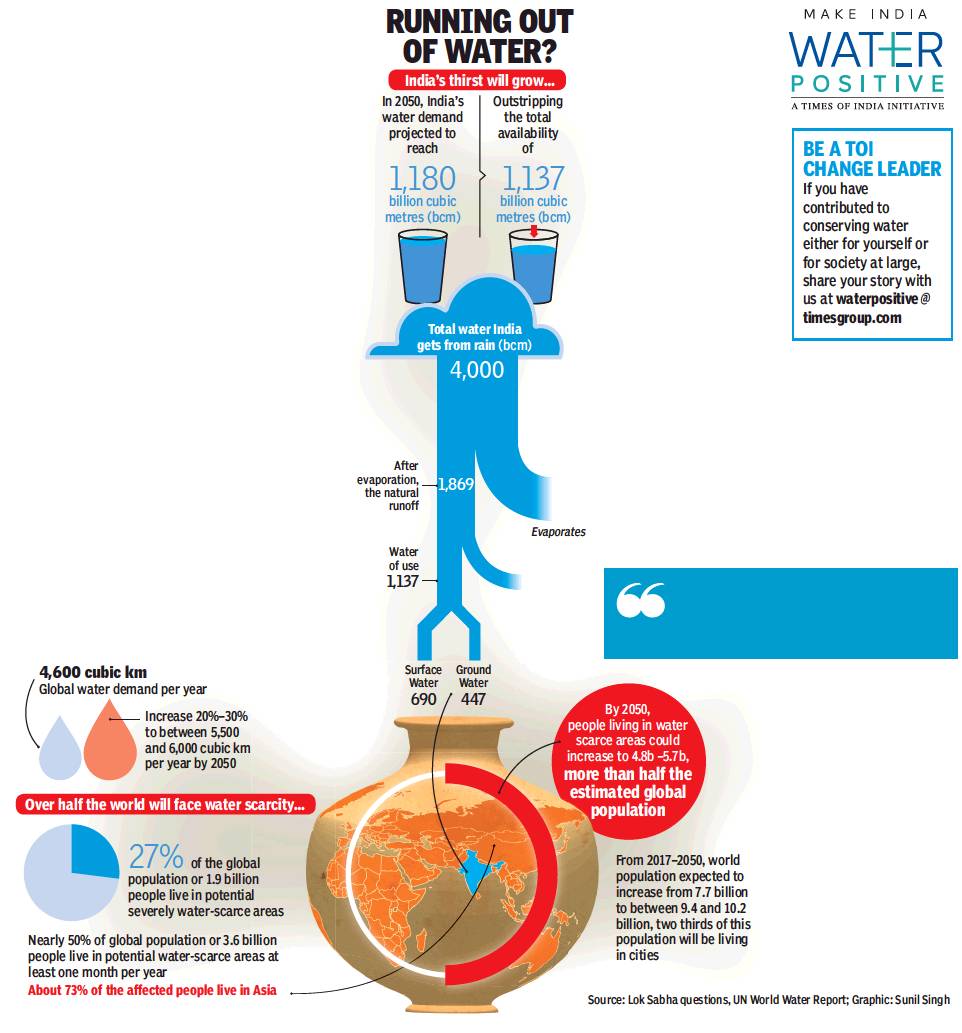

The demand for water is set to outpace supply by a wide margin

With demand for water expected to rise further, the future appears extremely uncertain. The forecast of a below normal monsoon for the second consecutive year has brought the focus on the perilous state of water resources in the country, but India’s water crisis has been in the making for a long time. The rapid growth of population and its growing needs has meant that per capita availability of fresh water has declined sharply from 3,000 cubic metres to 1,123 cubic metres over the past 50 years. The global average is 6,000 cubic metres. As water demand is expected to rise further, the future does not appear rosy.

Future projection

The demand supply mismatch is more severe in certain areas. In urban areas, where the demand of 135 litres per capita daily (lpcd) is more than three times the rural demand of 40 lpcd, the scarcity assumes menacing proportions. Already, Delhi and Chennai are fed with supply lines stretching hundreds of kilometres. According to projections by the UN, India’s urban population is expected to rise to 50% of the total population by 2050. This would mean 840 million people in the most water-starved parts of the country compared with 320 million today. The issue of inequity in water availability has already proved to be fertile ground for several inter-state and intra-state disputes, and unless mitigating steps are taken now, these conflicts would only escalate.

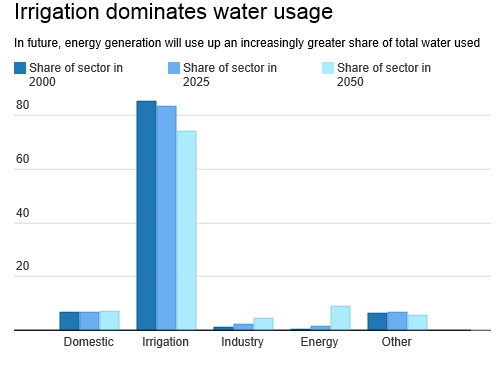

Future projection breakup

By 2050, energy generation is set to assume a much larger proportion of water usage. This should further nudge India towards renewable resources since thermal power plants are highly water-intensive and currently account for maximum water usage among all industrial applications. In order to match rapidly increasing demand, India needs to make judicious use of its two sources of fresh water — surface water and groundwater. Surface water — with rivers as its main source — is being relentlessly utilised through dams. These dams have robbed some rivers of their usual water flow, while diverting the course of others. As much as 55% of India’s total water supply comes from groundwater resources, which is also a cause of concern. Unbridled exploitation by farmers has led groundwater levels to plummet dangerously across large swathes of the countryside. Groundwater is critical to India’s water security. Irrigation, of which over 60% comes from groundwater, takes up over 80% of total water usage in India. Besides, nearly 30% of urban water supply and 70% of rural water supply comes from groundwater.

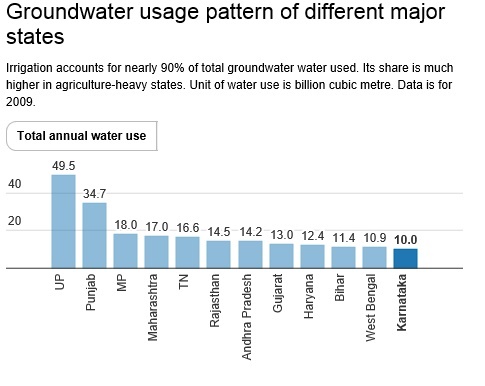

Pattern of ground water usage

The absence of rational water policies have led to the relentless exploitation of groundwater resources. Politicians looking to please the large farm vote-bank have provided massive subsidies on equipment and electricity required to mine groundwater. “By far the most powerful factor, which explains why groundwater irrigation grew faster in India than elsewhere, is the regime of flat rate tariff and power subsidies that India has introduced since the beginning of Green Revolution,” a 2012 study by the International Water Management Institute (IWMI) said.

Groundwater recharge

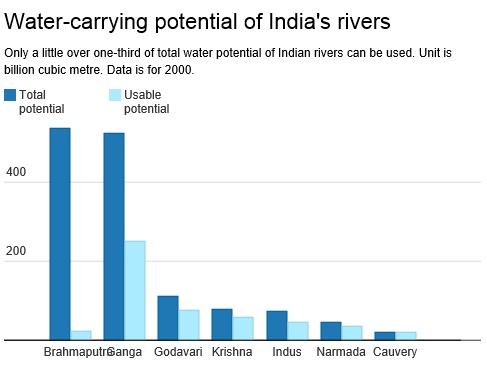

While India is blessed with some of the largest river systems in the world, a significant part of this water is rendered unavailable for use due to natural circumstances. For example, Brahmaputra has the highest total water potential of all rivers in India, but only about 4% of this can be successfully used because the mountainous terrain through which it flows makes further extraction impossible.

Rivers

Of the total potential of nearly 1,900 billion cubic metres (bcm) in India, only about 700 bcm can be utilized. The use of surface water is also affected by dams. With over 5,000 dams, India is behind only China and US on this count. While facilitating irrigation and electricity generation, the dams are adversely affecting water quality in the country.

Dams

“The irrigation benefits accruing from dams are largely illusory and far less than what is expected when they are planned,” said Tushar Shah, a water expert and senior fellow at IWMI. “Eventually, dams turn out very unattractive from a socio-economic perspective.”

Several scientific studies, including one by the United Nations Environment Programme in 2001, emphasize that dams have two main adverse effects on rivers. First, dams alter the chemical content and temperature of water. Water stored by dams has a temperature distinctly different from the rest of the river, and being stagnant, picks up unwanted things such as sand, besides encouraging algal bloom. Second, dams reduce the natural quantity of water flowing through downstream areas.

Water crisis in major cities

22 of India's 32 big cities face water crisis

Dipak Kumar Dash, TNN | Sep 9, 2013

Experts say that population of cities such as Jamshedpur, Dhanbad and Kanpur have increased manifold, resulting in increased demand for water. (TOI photo by Balish Ahuja)

NEW DELHI: Water scarcity is fast becoming urban India's number one woe, with government's own data revealing that residents in 22 out of 32 major cities have to deal with daily shortages.

The worst-hit city is Jamshedpur, where the gap between demand and supply is a yawning 70%. The crisis is acute in Kanpur, Asansol, Dhanbad, Meerut, Faridabad, Visakhapatnam, Madurai and Hyderabad — where supply fails to meet almost 30% of the demand — according to data provided by states which was placed in the Lok Sabha during the recently-concluded Parliament session by the urban development ministry.

The figures reveal that in Greater Mumbai and Delhi — which have the highest water demand among all cities — the gap between demand and supply is comparatively less. The shortfall is 24% for Delhi and 17% for Mumbai. However, the situation is worse than that.

For example, in Delhi, 3,156 million litres of water (MLD) is supplied against the requirement of 4,158. But around 40% of the supply is lost in distribution resulting in a much wider gap between demand and supply than what's recorded.

"In official records, many cities might be getting adequate water. But because of faulty engineering and poor maintenance, the actual availability is much less," said Dilip Fouzdar, a water resource management professional.

He added that though Mumbai gets good rains in comparison to many other big cities, very little of this is actually harvested. "A robust system to recharge ground water can make the city avoid any water shortage," Fouzdar said.

Experts say that population of cities such as Jamshedpur, Dhanbad and Kanpur have increased manifold, resulting in increased demand for water. But the deeper problem is one of short-sightedness, they said — governments wake up to water demand in a city after the situation has become acute. One such example is Gurgaon, where a major water channel was built almost 15-20 years after large-scale development happened.

The government records show 10 major cities in the country either meet daily water requirements or have surplus supply. Nagpur tops this list, reporting 52% extra supply while Punjab's industrial city, Ludhiana, has 26% surplus supply. Other cities managing to meet their water demand include Vadodara, Rajkot, Kolkata, Allahabad and Nasik.

What's also a cause for concern is that majority of the cities are depending on water sources from outside.

In Kochi, the daily water demand is 274 MLD while the supply is 250 MLD per day. Officially, daily water supply in the city is enough to meet almost 90% of the demand provided there is no loss or leakage in distribution.

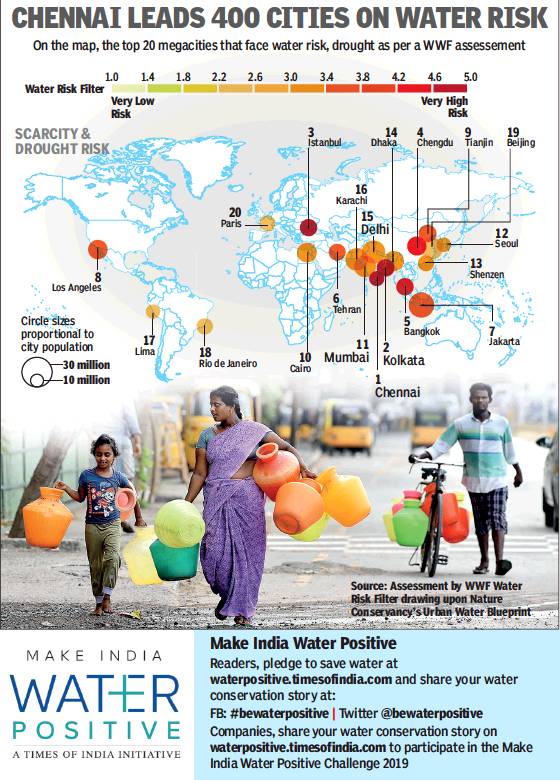

Four Indian water vulnerable cities in world’s top 20/ 2018

June 25, 2019: The Times of India

From: June 25, 2019: The Times of India

Four from India in top 20 water vulnerable megacities

A Study Of 400 Cities With Over 10 Million People Revealed That The Top 20 Comprised Those With High Scarcity And Those That Saw Floods

Just because your city suffered floods doesn’t mean you have water. Ask Chennai where 11 million are going without water.

Chennai’s severe water crisis this year is “one step worse” than Cape Town’s in 2018 — where reservoirs dropped to dangerously low levels, because emergency measures had to be taken to ensure even basic drinking water for residents, says Alexis Morgan, lead at WWF’s Global Water Stewardship. Morgan says, “What is perhaps even more perverse is that mere years ago, Chennai was exposed to devastating floods and experienced some of the wettest conditions in many years resulting in some 1.8 million people being displaced, the loss of over 500 lives, and economic damage over $3 billion. From too wet to too dry in a matter of four years.”

Chennai’s situation though is “unsurprising”, Morgan says. In an evaluation of 400 cities globally in 2018 with focus on megacities facing high combined levels of water scarcity — recent and projected drought, Chennai emerged in top position as the city facing the most severe water scarcity and drought. There are four Indian cities in the top 20 megacities with populations above 10 million. Chennai aside, Kolkata ranks at number 2, Mumbai at 11 and Delhi at 15. The study drew on The Nature Conservancy’s ‘Urban Water Blueprint’ and used WWF’s ‘Water Risk Filter’, global water management initiatives.

Large cities, mostly located along banks of large rivers, are vulnerable because for the most part, the river-systems are “vastly over-allocated and mismanaged”, Morgan notes. Drought to flooding are the “front edge of climate change”. Add to that the loss of wetlands, especially in a city such as Kolkata, and the looming crisis of floods and depleting water sources are evident. The world has lost 35% of its wetlands since 1970 and is losing them three times faster than forests, reports have noted.

Wetlands are key. Over half of Kolkata’s waste water once drained into the East Kolkata Wetlands without any need to treat the sewage. But as the wetlands shrink, the city, activists have time and again cited, loses its natural waste water tank, and in the absence of enough sewage treatment plants, the waste water goes straight into the river. A Ramsar protected site, the EKW was such an efficient system of canals and ponds that treated the city’s waste water that the sewage treatment plants were not sanctioned here under the Ganga Action Plan.

EKW was described as a “rare example of environmental protection and development management” by the Ramsar Convention, but such is the degree of encroachment that the National Green Tribunal on May 30 directed fencing of the site. The state may also have to reply to why a 2011 order on not issuing any further no-objection certificates for construction was revoked in 2017.

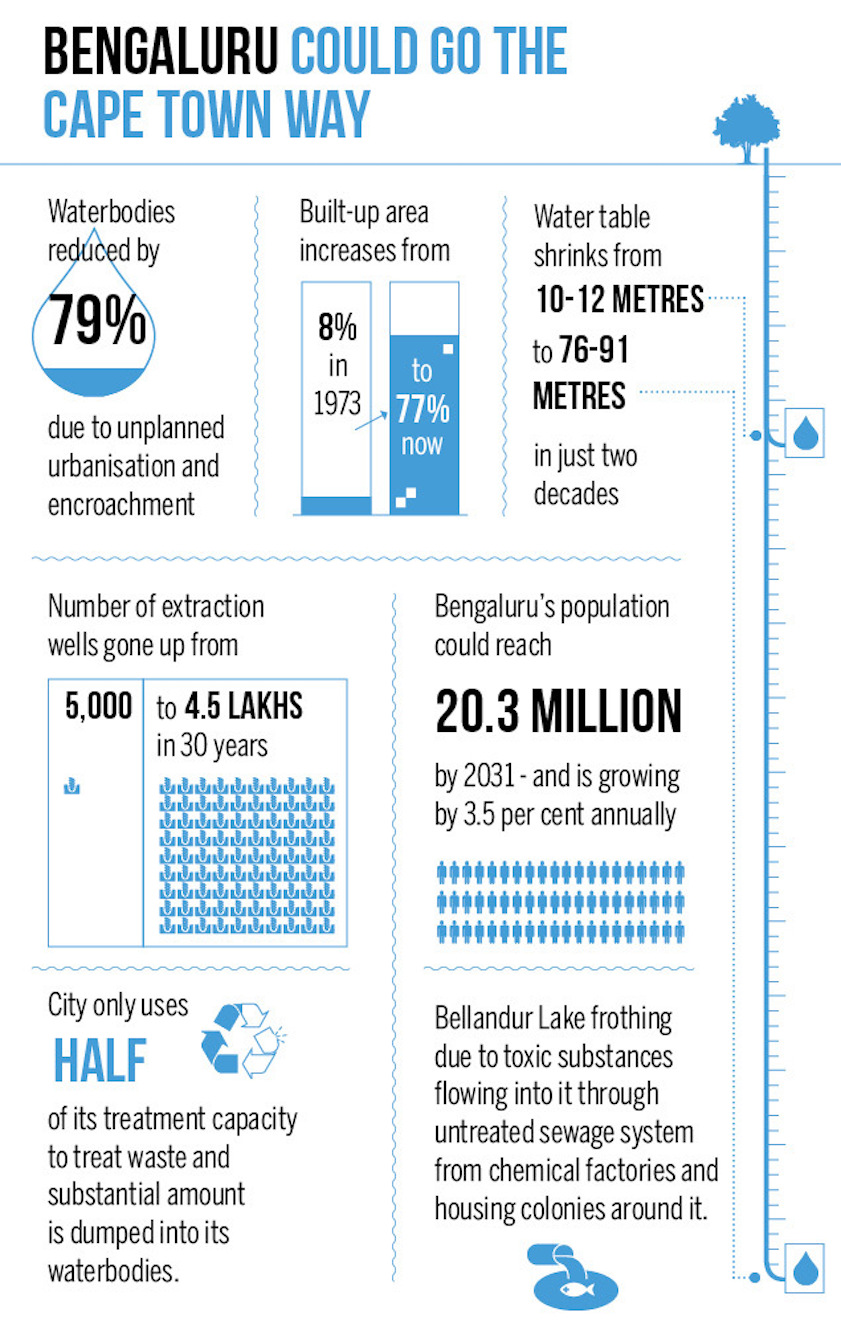

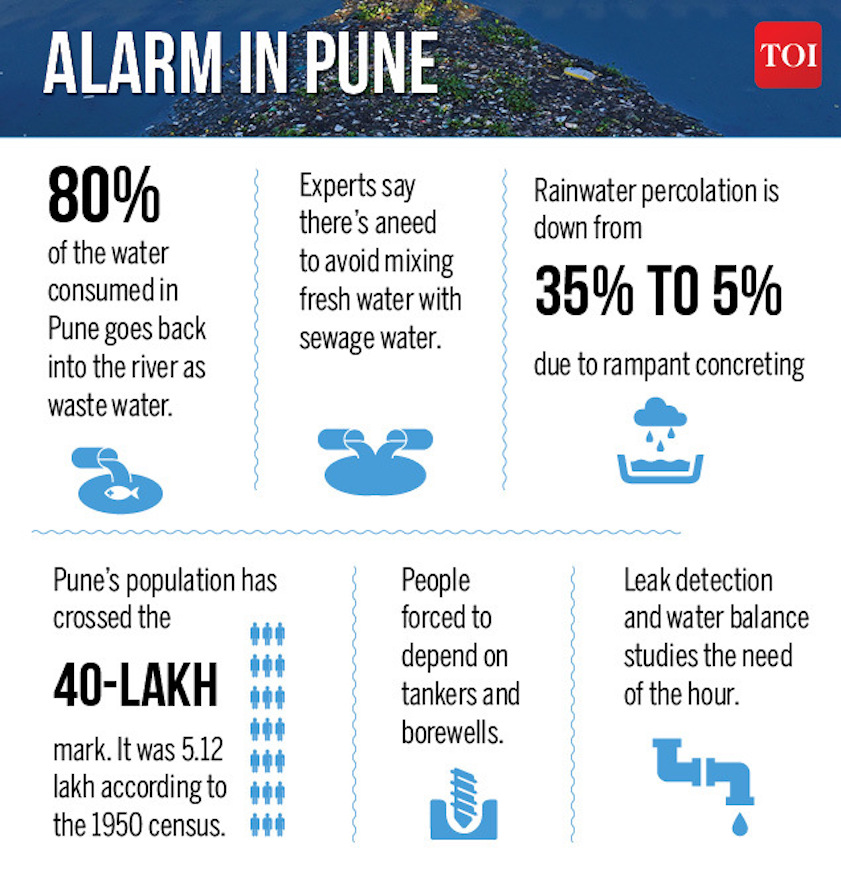

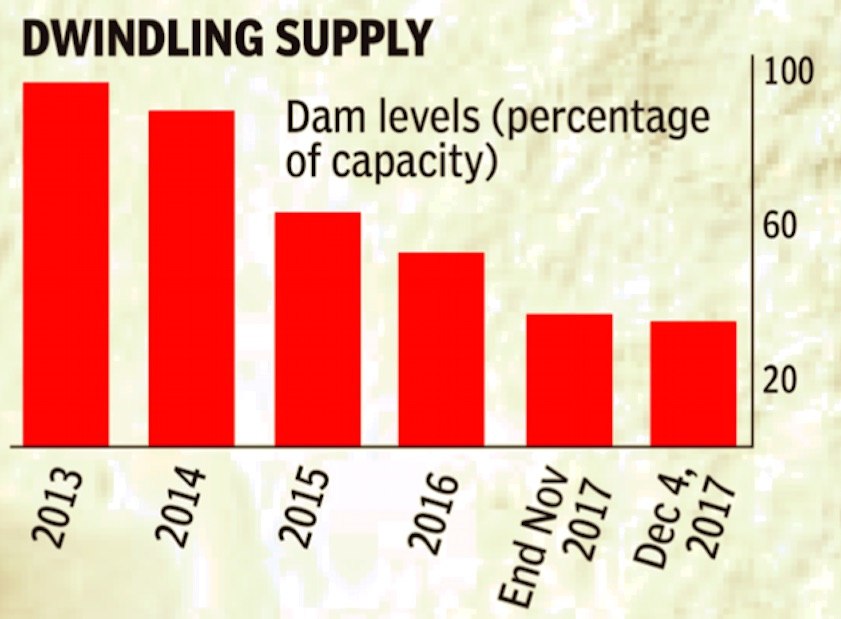

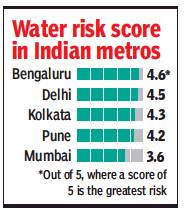

Bengaluru, Pune/ 2018

March 23, 2018: The Times of India

From: March 23, 2018: The Times of India

From: March 23, 2018: The Times of India

From: March 23, 2018: The Times of India

From: March 23, 2018: The Times of India

From: March 23, 2018: The Times of India

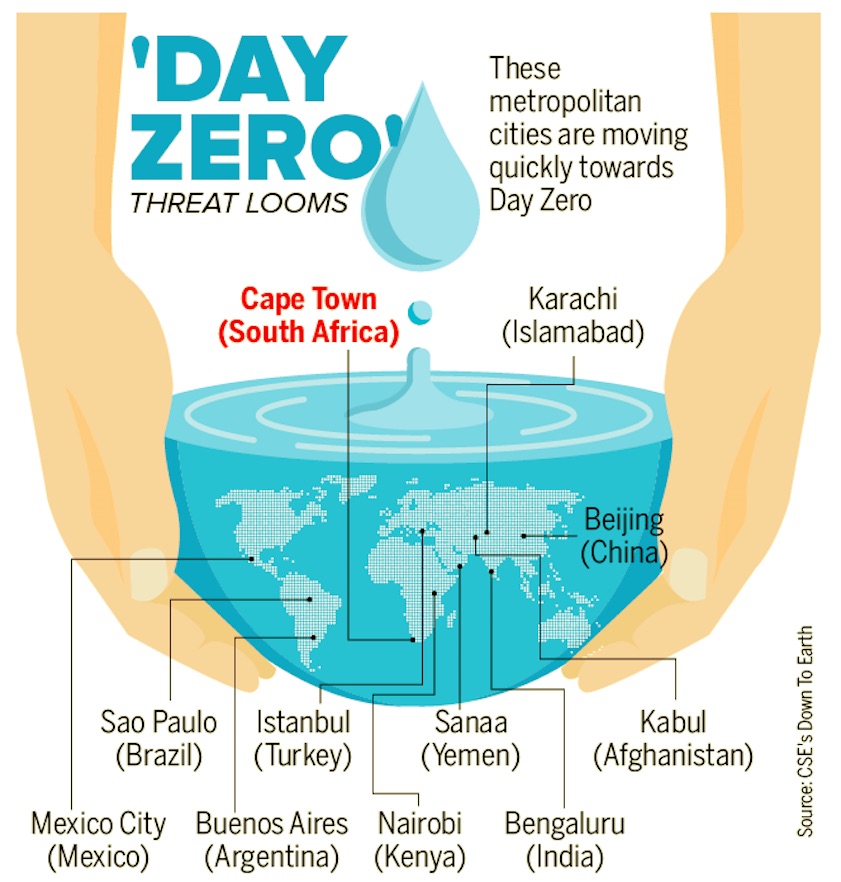

HIGHLIGHTS

Some 400 million people live in cities with a perennial water shortage, and the number is expected to go up to an alarming one billion by 2050

Urban water demand, in particular, is expected to go up by a significant 80% by 2050

Bengaluru is one of the 10 metropolitan cities besides Cape Town that is fast moving towards ‘Day Zero’ - a situation when taps start running dry.

Ahead of World Water Day being observed today, an analysis by Down To Earth, a magazine published by green think-tank Centre for Science and Environment, showed that at least 200 cities globally are facing a serious water crisis.

Sounding the alarm bells, Sunita Narain, director general of CSE, said, “Be it Cape Town, Bengaluru or Chennai, there isn’t much difference between these cities. They are all witnessing a common present. The important question to ask is whether these cities can create and move toward a common future that is water secure because it is water wise.”

CSE REPORT FINDINGS

The report analysed the findings of several global studies on water use and availability of resources and noted that 36% of the cities across the world will face a water crisis by 2050 and the urban water demand is expected to go up by a whopping 80% from the current level by 2050.

Some 400 million people live in cities with a perennial water shortage, and the number is expected to go up to an alarming one billion by 2050.

Besides Bengaluru, the list of 10 cities facing ‘Day Zero’ include Beijing (China), Mexico City (Mexico), Sanaa (Yemen), Nairobi (Kenya), Istanbul (Turkey), Sao Paulo (Brazil), Karachi (Pakistan), Buenos Aires (Argentina) and Kabul (Afghanistan).

GRIM WATER CRISIS IN BENGALURU

Experts say Bengaluru is on the verge of an imminent water crisis, with the city’s water table shrinking massively in just two decades. The city could follow Cape Town to become the first Indian city to run out of water unless urgent measures are taken.

“Recharge of groundwater is minimal due to unplanned urbanisation. The city only uses half of its treatment capacity to treat the waste and as a result a substantial amount of waste is dumped into the water bodies,” according to the Down To Earth report.

"There is a severe scarcity of water here," said 30-year-old Nagraj, who moved to the suburban neighbourhood of Panathur a decade ago and has seen it transformed by rampant construction.

"The future will be very difficult. It is impossible to imagine how they will find water, how they will live. Even if we dig 1,500 feet (450 metres) down, we are not getting water."

Once known as India's garden city for its lush green parks, Bangalore was built around a series of lakes created to form rainwater reservoirs and prevent the precious resource from draining away.

Many have now been concreted over to build apartment blocks with names like Dream Acres and Strawberry Fields to house those who have flocked here during India's outsourcing boom.

Many of the lakes that remain are heavily polluted. Bellandur has become so toxic it spontaneously catches fire, and emits clouds of white froth so large authorities have had to build barriers to keep it from spilling onto the road.

"The city is dying," said T V Ramachandra, an ecologist with the Indian Institute of Science.

"If the current trend of growth and urbanisation is allowed (to continue), by 2020, 94 percent of the landscape will be concretised,” he added.

Most of the city's municipal water is supplied by the Cauvery river, whose waters flow through Karnataka and neighbouring Tamil Nadu before emptying into the Bay of Bengal, and have been bitterly disputed for more than a century.

Two years ago, an order to release extra water from the river to ease a shortage threatening crops in Tamil Nadu sparked deadly protests in Bangalore that forced hundreds of companies to close.

Last month the Supreme Court stepped in, altering the river-sharing arrangement in Karnataka's favour citing Bangalore's dire need.

Ecologist Ramachandra, meanwhile, said Bangalore has enough annual rainfall to provide water for its estimated 10 million people without resorting to borewells or rivers -- if only it could harvest the resource more effectively. "If there is a water crisis, we should not think about river diversion. We should think about how to retain the water," he said, blaming "fragmented, uncoordinated governance" for the crisis.

PUNE MUST AVOID CAPE TOWN-LIKE SITUATION

Bengaluru is not the only Indian city that has to reason to worry. In Pune, an institutional approach, instead of an individual one, is required to preserve its water.

“Think of water crisis and the first thing that comes to mind is Cape Town, or perhaps Bangalore. These cities are facing an acute water crisis as their groundwater tables have dropped rapidly. Cities depend on annual average rainfall and natural resources for their water requirements. In Pune, we receive an annual average rainfall of 750mm. We have five rivers, of which two have run dry and three have been reduced to sewage lines,” said Col Shashikant Dalvi (retd), the founder of Parjanya, that does rainwater harvesting in the city.

“Newly-developed areas of Baner, Balewadi and Vimannagar are already facing an acute water scarcity. There is no mechanism for groundwater recharge. The time has come to identify problems, make communities responsible,” said Suneel Joshi, convenor of Jal Biradari, Pune.

He also raised the issue of landfilling, which leads to water contamination. “The polluted water travels to Ujani dam, affecting the people staying in 28 rural areas. There is an urgent need for knowledge sharing and sensitization of people at all levels. We need continuous education about water and its management at school and college levels,” Joshi added.

“We are water-illiterate people who do not understand the concept of water footprint. Groundwater Surveys and Development Agency in Pune had undertaken a study to map the aquifer quality and quantity in Pune, but this report was never put in the public domain. There are areas where groundwater should not increase and others where rooftop rainwater harvesting is necessary,” said Vijay Paranjpye, managing trustee of Gomukh Trust.

THE CAPE TOWN CRISIS

Alarm bells began ringing around the world when Cape Town announced it was running out of water. One of the richest cities of Africa, it could soon have no water. Many reports have estimated that the city’s taps will run dry this year, possibly by July-August.

In 2014, Cape Town’s prized dams stood full after several years of substantial rainfall. Inf act, C40, a group of cities focused on climate change worldwide, had in 2015 awarded Cape Town its ‘adaptation implementation’ prize for water management.

A three-year drought, however, meant the the situation took a 360 degree turn, forcing South Africa's second city to slash residential water consumption by more than 60%.

The water crisis has hit this popular tourist city hard and fast. To deal with the crisis, the city introduced the idea of ‘Day Zero’ in a bid to substantially cut water use.

The term “Day Zero’ was thus coined to mark the day the city was expected to run out of water. The date was first marked as June 4, however, strict rationing pushed the date to July 9. Earlier this month Cape Town officials said that if no rainfall comes then "Day Zero", when the taps are predicted to run dry, would be pushed back to August 27 from July 9, and that the bullet could be dodged completely this year.

"Provided we continue our current water savings efforts, Day Zero can be avoided completely this year," the city’s deputy mayor said in a statement.

"The city now projects that, if there was to be no rainfall, Day Zero would arrive on 27 August 2018. As this date falls deep within the normal rainfall period, it is no longer appropriate to project the date without any consideration of rainfall," the statement added.

Increased water saving by residents was responsible for the date being postponed, according to officials of this city of four million people. It said provincial farmers who released a large amount of water from private dams to help the city also contributed.

Officials insist the city’s residents must continue to regulate the use of treated water. Residents must use less than 50 litres (13.2 gallons) per person daily to avoid total depletion - less than one-sixth of what the average citizen uses.

In addition, the city is setting up 200 emergency water stations outside groceries. Each will have to serve 20,000 residents.

WORLD WATER FORUM OPENS

Even as the world grapples with this crisis, the United Nations has warned that some 5.7 billion people may run short of drinking water by 2050.

In the backdrop of this dire warning, the 8th World Water Forum is presently being held in Brazil, bringing together 15 heads of state and government, 300 mayors and dozens of experts. In total, an estimated 40,000 people were expected to attend.

Brazil's President Michel Temer’s opening remarks made it evident the world was taking the matter seriously. “There is simply no time to lose,” he warned.

The main focus was on the specter of supplies collapsing in major urban centers, as almost happened in Cape Town this year.

"This is the consensus," Brazil’s president remarked. "Life on earth is threatened if we don't respect nature's limits."

The forum comes in the wake United Nations’ 2018 World Water Development Report, which said 3.6 billion people, or half the world's population, already live in areas where water can be scarce at least one month a year. That could rise to 5.7 billion people by 2050, the report said.

NATURE-BASED SOLUTIONS

In an example of how nature-based practices do help, New York has protected the three largest watersheds that supply water to the city since the late 1990s through forest preservation programmes and paying farmers to be environmentally friendly.

"Disposing of the largest unfiltered water supply in the US, the city now saves more than $300 million yearly on water sea treatment and maintenance costs," the UN noted.

China's "Sponge City" project is another example of of how water availability could be improved. By 2020, China plans to build 16 pilot projects across the country with the aim of recycling 70 percent of rainwater through greater soil permeation, retention and storage, water purification and restoration of adjacent wetlands.

"These solutions are cost-effective" and not more expensive than traditional systems, according to the UN.

It also pointed to estimates that global agricultural production could increase by about 20 percent with greener water management practices.

In addition to improving water availability and quality, "it is possible to increase agricultural production per hectare with better water management" and thus feed more people, said Stefan Uhlenbrook, program coordinator at the UN World Water Assessment Forum.

"Green" infrastructure also helps fight erosion, drought and flood risks while boosting soil quality and vegetation.

And indigenous peoples could be involved in implementation, something which was not the case in "grey" infrastructure," the report said.

However, only marginal use was being made of such nature-based solutions. "Accurate figures are not available", but investments in these techniques "appear to be less than one percent... of total investment in infrastructure and water resource management," according to the report.

17% of cities/ towns face water shortage; TN tops list/ 2019

Dipak Dash , July 8, 2019: The Times of India

From: Dipak Dash , July 8, 2019: The Times of India

About 17% notified cities and towns in India face water shortage, according to a list prepared by the central government. Among the states, Tamil Nadu has maximum number of such urban areas followed by Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh. All the four municipal areas in Delhi including the posh NDMC zone have been included in the list of 756 “water stressed” urban areas out of total 4,378 which are governed by municipal bodies.

All urban areas surrounding the national capital such as Ghaziabad, Noida and Faridabad have been facing similar shortage.

The housing and urban affairs ministry has come out with the names of cities and towns on the lines of Jal Shakti ministry, which has identified 255 districts and 1,597 blocks as water stressed. The urban affairs ministry has also prepared a plan to undertake intensive campaign for water conservation, recycle and reuse of grey water.

The Centre has also asked states and the urban local bodies (ULBs) to carry out focused activities in two phases; July 1 to September 15 and October 1 to November 30. It has circulated a template for effective monitoring of the activities and performance on implementation of rainwater harvesting, rejuvenation of water bodies, reuse of treated waste water and plantation.

It has also asked all ULBs to set up a cell for effective monitoring of rainwater harvesting and revival of at least one water body in their respective areas. The “Rainwater Harvesting Cell” will monitor the extent of groundwater extraction and groundwater aquifer recharge and display the information at prominent locations for public awareness. The ministry has also asked ULBs to ensure all new building permissions must have rainwater harvesting structures incorporated.

Delhi/ 2020

Graphic courtesy: The Times of India, May 4, 2016

See graphic:

Water crisis in Delhi. Figures are in metre below the ground level, MBGL, April 2015-April 2016

5 urban Himalayan towns are running dry/ 2020

Vishwa Mohan, March 2, 2020: The Times of India

Thirteen towns across four countries, including five from India (Mussoorie, Devprayag, Singtam, Kalimpong and Darjeeling), in the Hindu Kush Himalayan (HKH) region are facing increased water insecurity, a study published in the journal ‘Water’ on Sunday said. It also explained the reasons behind the phenomena where “urban Himalaya is running dry” despite being in a region of high water availability.

The remaining eight towns are in three countries — Nepal (Kathmandu, Bharatpur, Tansen and Damauli), Pakistan (Murree and Havelian) and Bangladesh (Sylhet and Chittagong). Though Shimla was not part of this study as one of the 13 urban sites, reasons of increased water insecurity there in the summer could be explained by this phenomena which is marked by poor water governance, lack of urban planning and climate-related risks.

The study, the first of its kind on the HKH region, said inter-linkages of water availability, water supply systems, rapid urbanisation and consequent increase in demand (both daily and seasonal) were leading to water insecurity in these towns which have shown increase in population and tourist flow.

“There is a high dependence on springs (ranging between 50% and 100%) for water supply in three-fourths of the urban areas. Under current trends, the demand-supply gap may double by 2050. A holistic water management approach that includes springshed management and planned adaptation is , therefore, paramount for securing safe water supply in the urban Himalaya,” said Anjal Prakash, one of the editors of the report on the study ‘Mapping Challenges for Adaptive Water Management in Himalayan Towns’.

2020: rise in water risk, city-wise

Chandrima.Banerjee, November 3, 2020: The Times of India

From: Chandrima.Banerjee, November 3, 2020: The Times of India

With 31 cities exposed to serious water security risks, India has run into a greater challenge than entire continents of Africa or Europe, data from a study by the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) show. Consequently, India faces the second highest basin risk in the world, only better than Palestine.

The analysis, ‘Water Risk Filter’, focuses on two things — water stress cities face now and the projected increase by 2050. “If you go just by water risk now and that projected for 2050, Indian cities dominate the list of cities facing very high water risk,” Ariane Laporte-Bisquit, international lead on the project, told TOI.

On a scale of 1 to 5, anything over 3 is ‘high risk’ and over 4 is ‘very high risk’. Of the 31 Indian cities that are under water stress, 26 scored over 4, meaning they face ‘very high risk’ right now. The second worst placed region in the world, west Asia, has only six such cities. Asia (barring China) has five, North America has three, China has two, central America has one. None of the other continents has any city facing very high water risk. Globally, the steepest escalation has been projected for Alexandria in Egypt, with a 16% spike by 2050. The highest increase in risk among Indian cities has been projected for Jaipur (11%) and Indore (10%).

Drinking water

See graphic:

Shortage of Drinking Water in India, the magnitude of the problem in 2017

in the rural areas

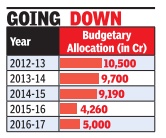

Funds decline after 2013-14

The Times of India, Apr 13 2016

Funds for rural water drying up

Dipak Dash The budgetary allocation for drinking water in rural areas has been decreasing since 2013-14 even as certain parts of the country reel under acute shortage of water for the second consecutive year.

The maximum reduction was registered in 201516 and 2016-17 owing to a greater devolution of funds to states under the 14th Finance Commission.

An analysis of the budgetary allocation for drinking water in rural areas over the past four financial years shows that the maximum amount earmarked was approximately Rs 10,500 crore in 2012-13.The allocation was the lowest in 2015-16 at Rs 4,260 crore.Though it has been hiked for this fiscal, the increase is negligible.

Sources said the issue was discussed at a review meeting on drought chaired by the cabinet secretary on Monday . A fact causing worry is that many projects already started may get impacted because of lower central support.

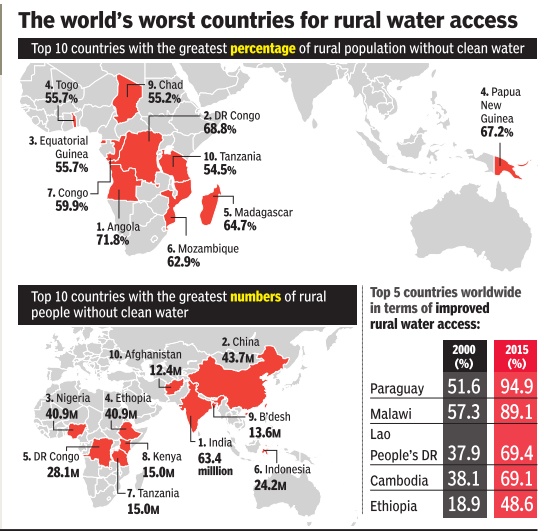

Rural population with no clean drinking water , March 2017

See graphic:

Top 10 countries with the greatest percentage and numbers of rural population without clean water

2019/ The New York Times’ warning bell

Nov 25, 2019: The Times of India

Bryan Denton , a photographer based in India, and Somini Sengupta , the Times’s global climate reporter, visited cities and villages around India to see how climate change and misguided policies are upending the country’s relationship to a precious resource.

Climate change is now messing with the monsoon, making seasonal rains more intense and less predictable. Worse, decades of short-sighted government policies are leaving millions of Indians defenseless in the age of climate disruptions – especially the poor.

After years of drought, a struggling farmer named Fakir Mohammed stares at a field of corn ruined by pests and unseasonably late rains. Rajeshree Chavan, a seamstress in Mumbai, has to sweep the sludge out of her flooded ground floor apartment not once, but twice during this year’s exceptionally fierce monsoon. The lakes that once held the rains in the bursting city of Bangalore are clogged with plastic and sewage. Groundwater is drawn faster than nature can replenish it. Water being water, people settle for what they can find. In a parched village on the eastern plains, they gather around a shallow, fetid stream because that’s all there is. In Delhi, they worship in a river they hold sacred, even when it’s covered in toxic foam from industrial runoff. In Chennai, where kitchen taps have been dry for months, women sprint downstairs with neon plastic pots under their arms when they hear a water truck screech to a halt on their block.

This year, India experienced its wettest September in a century; more than 1,600 people were killed by floods; and even by the time traditional harvest festivals rolled around in October, parts of the country remained inundated.

Even more troubling, extreme rainfall is more common and more extreme. Over the last century, the number of days with very heavy rains has increased, with longer dry spells stretching out in between. Less common are the sure and steady rains that can reliably penetrate the soil. This is ruinous for a country that gets the vast share of its water from the clouds.

The problem is especially acute across the largely poor central Indian belt that stretches from western Maharashtra State to the Bay of Bengal in the east: Over the last 70 years, extreme rainfall events have increased threefold in the region, according to a recent scientific paper, while total annual rainfall has measurably declined.

“Global warming has destroyed the concept of the monsoon,” said Raghu Murtugudde, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Maryland and an author of the paper. “We have to throw away the prose and poetry written over millennia and start writing new ones!”

India’s insurance policy against droughts, the Himalayas, is at risk, too. The majestic mountains are projected to lose a third of their ice by the end of the century if greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise at their current pace.

But, as scientists are quick to point out, climate change isn’t the only culprit to blame for India’s water woes. Decades of greed and mismanagement are far more culpable. The lush forests that help to hold the rains continue to be cleared. Developers are given the green light to pave over creeks and lakes. Government subsidies encourage the over-extraction of groundwater.

The future is ominous for India’s 1.3 billion people. By 2050, the World Bank estimates, erratic rainfall, combined with rising temperatures, stand to “depress the living standards of nearly half the country’s population.”

The Marathwada region, stretching out across western India, is known for its cruel, hot summers. Hardly any rivers cut through it, which means that Marathwada’s people rely almost entirely on the monsoon to fill the wells and seep into the black cotton soil.

Marathwada is also an object lesson in how government decisions that have nothing to do with climate change can have profoundly painful consequences in the era of climate change.

In October, just weeks before the traditional harvest season, Fakir Mohammed led me through his family’s one-and-a-half-acre plot of land. A neem tree stood in the middle of the fields. Lie under it, Mr. Mohammed said with pride, and you’ll never get sick. The same could not be said of his land.

The rains had been deficient for most of the last nine years. This year, they came late, and when they came, the thirsty ground drank everything.

Mark-II Handpump

India Today.in , Water,Water,Everywhere “India Today” 15/12/2016

1978

Mark-II Pumps

Water, water, everywhere

At a time when electricity had not quite reached the far-flung villages of India, the only way to access water-especially in times of drought-was to source it manually from wells. At first, wells were dug by hand; later, as powerful drill machines were developed, bore wells became the norm. To tap groundwater sources effectively, the Government of India joined hands with UNICEF to develop a more efficient manual handpump than the one in existence. After several rounds of trials, the government decided to adopt widespread installation of the 'Mark-II' pump. UNICEF agreed, spreading the technology to many other developing countries as well. The Mark II was based on the 'Sholapur pump', the most durable of its time, designed initially by a self-taught Indian mechanic. By the mid-1990s, five million pumps had been manufactured and installed. An improvement, the Mark III was also developed; these manual pumps are now exported to about 40 countries. Technological innovation has led to further upgrades as well, transforming the manual pump into a solar-powered thermal siphon pump in many places where piped water supply to homes is still a distant dream.

How Rajasthan’s desert tribes get clean water

Ramgarh (West Rajasthan) A traditional system of harvesting rainwater, beris have been lifesavers for both humans and animals in these parts for centuries. Shaped like a matka (pitcher), the shallow wells are dug up in areas with gypsum or bentonite beds that prevent rainwater from percolating downwards. Instead the water gets guided to the wells through capillary action.

“Last year, Ramgarh and neighbouring villages barely received any rain. But, even so, the beris were fully charged. One can draw 10,000 litres of clean water daily; it gets replenished overnight,“ says Chatar Singh (56), local eco warrior with masterly knowledge of water conservation in deserts.

His initiatives, with those of Sambhaav, an NGO that helps to restore aquifers, have led to the digging of dozens of new beris and revival of others that had fallen into disuse. The locals' trek for drinking water is not so long anymore.

The importance of beris gets underlined by what unfolds kilometres away . Water from the humongous Indira Gandhi canal gathers in a pond-like structure on its way to the filtering unit. The water, full of algae, looks unfit for consumption. Yet tractors line up to ferry it away in large cans. “Hum yahi pani peete hain (We all drink this water),“ says Suraj Singh Bhati, Class X, here to ferry water home.Near the Sagarmal Gopa branch of the canal a cow's rotting carcass lies.

On the outskirts of Netsi village, 23 beris are in use. The village has a huge cement tank that stores water released from the IG canal. But most women trek a kilometer to Viprasar, where the beris are.“Most of us drink the beris' water,“ says Mala Devi. Water from the IG canal has undeniably eased their woes but most villagers told TOI that taps often run dry .“We got water after a gap of five days,“ said Guddi of Ekalpar village. Traditional Netsi beris were made of wood. “They'd rot after a year. The new beris are built with long-lasting blocks of yellow stones that Jaisalmer is known for,“ says retired armyman Jitu Singh.

Success in these water harvesting projects resulted from partnering with locals. Netsi villagers offered the labour required to make the beris functional.Chatar says villagers were first motivated, while Sambhaav provided materials.

Chatar, who used to teach children of the tribal bhil community in Ekalpar and Dobalpar, once regarded the area's poorest villages, has over the last decade, worked on water conservation alongside Farhad, who routinely visits these villages. Part of their work is to help the bhils learn the traditional art of khadeen, a form of cultivation in arid regions where the ground's moisture is harnessed to grow wheat, mustard and black gram in the main. “We help them help themselves,“ says Farhad.

The bhils, largely a hunting community, would be asked to shift from one place to another by the local administration.“They did not know how to harness water. Sometimes they would lie down on the field to stop rainwater from escaping,“ recalls Chatar Singh, influenced by environmentalist Anupam Mishra's seminal book `Rajasthan Ki Rajat Boondein' (The Radiant Raindrops of Rajasthan).

The bhils were taught toba: a way to store rainwater for drinking, dhora: a technique to store rainwater for irrigation and chhapai: a method to use a `wall' of bushes to stop the spread of desertification. “We didn't know how to grow crops,“ says Padma Ram (60), a bhil who owns 75 bighas. In 2015, he earned Rs 3 lakh growing black gram.Such examples abound. The two bhil villages now boast 30 motorcycles and 15 tractors; unthinkable few years ago.

A distance from his village, Padma is building a mound three feet high, over 500 feet long. “The dhora will trap rain water,“ he says. Rain arrives late in Jaisalmer, plays hookey in Ramgarh at times. But the bhil is an optimist. “It will rain one day,“ he says. “When it does, I want to trap every drop.“

Karnataka, 2017: many areas depend on AP

Naveen Y, Karnataka's driest villages bank on Andhra for water, June 2, 2017: The Times of India

Villagers skip work, forego wages to make trips to the next state for both family & livestock's daily needs

Every morning, 42-year-old Lakshmi of Kondapura in Karnataka's Pavagada taluk crosses the inter-state border into Chikkanaduka village in Andhra's Ananthpur district and returns home with a pot of water. It's a 10km walk to and fro, and it means the daily wager has to forego her earnings. But the mother of two says: “We are lucky, because the neighbouring villages in Andhra Pradesh have sufficient borewells. The people there are supporting us.Otherwise, it is very difficult for us to live here. Thank God there's no border wall between the two states.“

The nearly 300 families living in Kondapura, 150km from Bengaluru, are facing acute water scarcity as drought ravages the entire region for the third year in a row. The weekly water tanker sent by the taluk administration is barely adequate.

The three government borewells in the village have dried up. Although there are two private borewells, the landlords refuse to share water. People save every drop for drinking and baths are a once-a-week luxury in Kondapura as well as neighbouring Vellur, Nagenahalli, Chikkanahalli and Siddapura villages in Pavagada taluk -the second-most arid region in the country after the Thar desert.

Water has become a perennial problem. “None of the officials bother about us,“ says Lakshmi bitterly .Parvathamma, her companion in the 10km water-walk, says: “Water is making us poor. We used to work as labourers and get daily wages, but we cannot work as we have to trek several hours for water.“ It's become a family occupation. “While I get two pots of water in the morning, my husband and two kids get six pots of water on our bicycle in the evenings,“ Parvathamma says. “Each family in the region owns a bicycle, basically used to transport water pots.“ Another village woman, 35-year-old Bhagya points out that villagers have to share the water with their cattle.

The water scarcity is also drying up the marriage prospects of local boys.Nagendra, a young college graduate from Chikkanahalli, says it's a struggle for families to find brides.“People are not ready to get their daughters married to boys in the village because there is no water. They prefer to seek bridegrooms on the other side of the border as water is not a problem there.“

Despite similar topography, how do Andhra villages have water while their Karnataka neighbours have none? The villagers attribute it to the Andhra government's resolve to solve the water problems of its tail-end areas. The HandriNeeva Sujala Sravanthi project sources Krishna wa ters through the Srisailam reservoir and supplies to Madakasira and adjoining areas on theder. The Andhra government has also built check dams and artificial water recharge structures.

Bhagya points out: “The borewells of Andhra villagers have water, and it's great that they are willing to share it with us. Hope our government wakes up soon.“

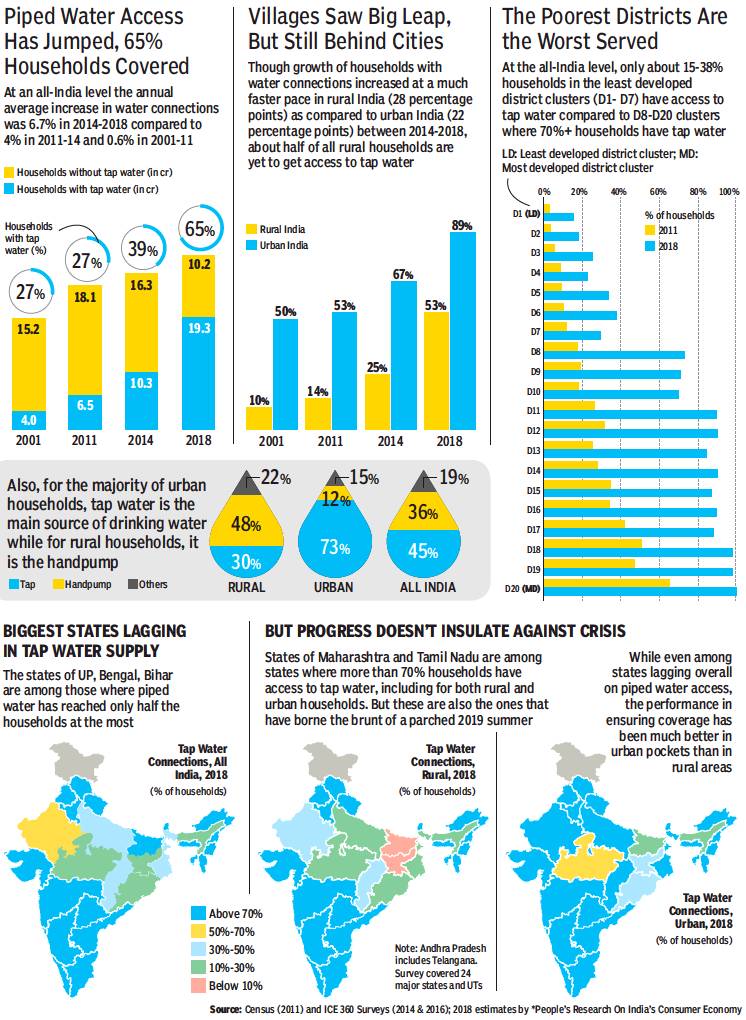

Piped water

2001-18

June 18, 2019: The Times of India

From: June 18, 2019: The Times of India

Large swathes of India are grappling with a severe water crisis under record maximum temperatures this summer. The prime drivers of the current water crisis — equally acute in rural areas in Maharashtra and elsewhere and a metro city like Chennai — are drying reservoirs and dipping groundwater levels. But while those require deeper solutions, India’s progres in building pipeline infrastructure that takes potable water to households is heartening. Close to 90% of urban households now have tap water connections, according to a survey by PRICE*. In his second term, PM Narendra Modi is focusing on piped water connection for all households by 2024 as a key goal. But getting water to flow from the taps, as the present water crisis shows, is another challenge altogether

See graphic:

Piped water in India and the Indian states, 2001-18.

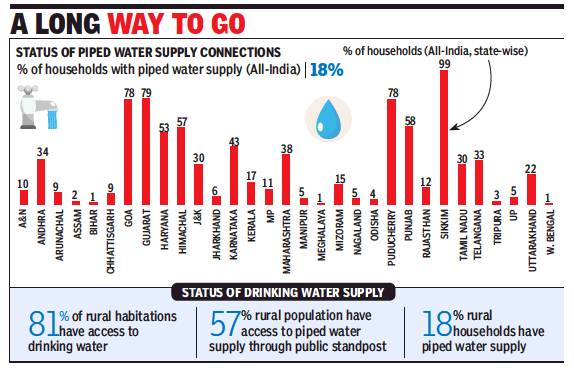

As in 2018

From: Dipak Dash, June 12, 2019: The Times of India

See graphic, '%age of households with piped water supply, state-wise and all- India, presumably as in 2018.'

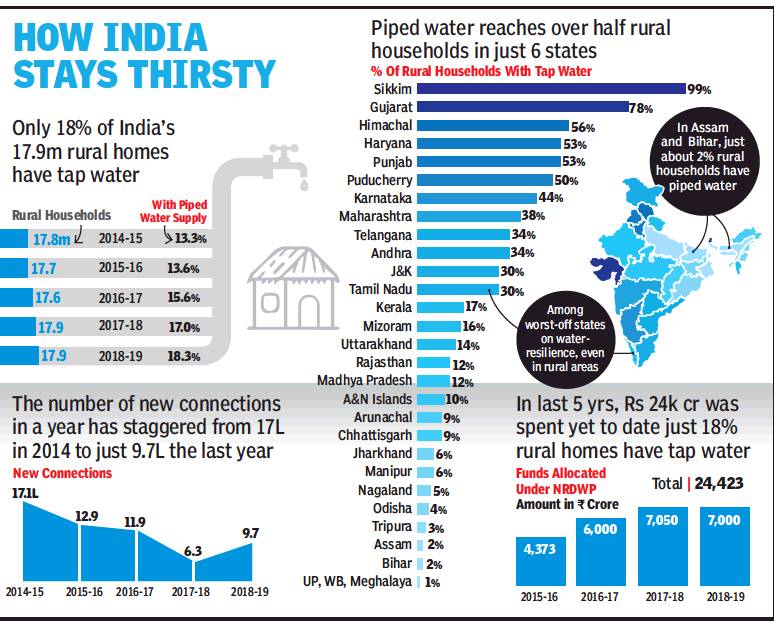

2014-19 + state-wise figures

Atul Thakur, June 27, 2019: The Times of India

From: Atul Thakur, June 27, 2019: The Times of India

Stories of severe water crisis in Indian cities have become routine every summer. Niti Aayog’s 2018 Composite Water Management Index (CWMI) report suggests that this crisis will only worsen. The report says 600 million people in India live in high to extreme water stress and clearly the strained water supply system is susceptible to collapse.

In a guidance note, the Central Public Health & Environmental Engineering Organisation (CPHEEO), the technical wing of the urban development ministry, has noted that 24x7 supply is the global norm.

CPHEEO stated that intermittent supply of water for a few hours a day is inefficient and susceptible to contamination. There are serious health risks and hence lower consumer faith. Nonstop supply with improved quality increases willingness to pay for the service, reduces wastage.

A pilot study in four cities in Karnataka showed that people started using less water when given 24x7 supply. The note pointed out that 30 or 40 years ago many urban areas in India had 24x7 water supply till rapid urbanisation made it unsustainable.

All developed countries supply drinkable tap water to citizens. A travel advisory by the US Center for Disease Control and Prevention says high-income countries in the Gulf — Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, UAE and so on — also provide drinkable tap water. Yet, in India, majority of the population doesn’t even have tap water supply leave alone tap water fit to drink. Data on piped water connections under the National Rural Drinking Water Programme (NRDWP) reveals the sorry state of affairs.

Government had launched NRDWP in April 2009. In 2013, guidelines were updated to focus on piped water supply. A CAG report on NRDWP pointed out the scheme that was supposed to provide piped water connection to 35% of rural households by 2017, had actually been able to provide piped water connections to barely 18.3% of rural households by . end of 2018-19.Data shows the slow progress under this scheme. In 2014-15, just 13.3% of India’s 17.8 crore rural households had piped water connection. In the past five years this improved by just over 5 percentage points.

Worse, the number of new connections each year has declined. In 2014-15, over 17 lakh new connections were provided. This slid to just 6.3 lakh new connections in 2017-18 before an uptick in 2018-19 to 9.7 lakh.

The CAG report pointed out that between 2012 and 2017, Rs 81,168 crore was spent on this programme and yet it could barely achieve half the target. The investment by central and state governments to provide rural India drinking water since Independence has been, without adjusting to inflation, Rs 2.4 lakh crore under various schemes, CAG notes , yet over 80% rural households don’t have piped water connections.

Only 5 states and one UT manage to provide piped water to at least half their rural population. NRDWP doesn’t provide data for fully urbanised states or UTs like Delhi and Chandigarh. Among large states, Odisha, Assam, Bihar, and UP, piped water connection is available to less than 5% of the rural population.

This sobering data provides the context in which to view Centre’s declaration it will make piped water the next big focus. It must be a priority, but it is just as evident that progress has been way below what’s needed.

2019- 2022: rural water supply in the states

Bihar, 2019-21

Nov 22, 2022: The Times of India

From: Nov 22, 2022: The Times of India

Bihar made a prodigious leap in tap-water coverage, from 1. 9% in 2019 to 87% in 2021. The state government said it had provided 1. 5 crore connections under its ‘Har Ghar Nal Ka Jal’ scheme, in addition to the 8. 4 lakh provided under the Centre’s ‘Har Ghar Jal’ scheme. This year, the coverage has “officially” improved to 96%, putting Bihar in the same league as Punjab and Himachal Pradesh. Only seven states and UTs, including Haryana and Gujarat, have 100% coverage.

Polluted drinking water

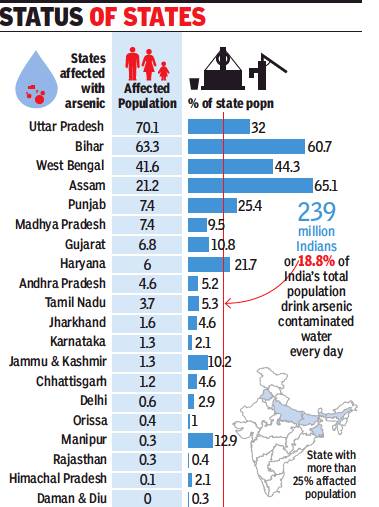

Arsenic levels in 2016

From: Radheshyam Jadhav, 19% of Indians drink water with lethal levels of arsenic, December 24, 2017: The Times of India

See graphic:

States affected with arsenic, 2016

Over 70m In UP Alone, Says Govt Data

About 239 million people across 153 districts in 21 states drink water that contains unacceptably high levelsof arsenic. In effect, they are being slowly poisoned.

Calculations based on information provided by the water resources ministry in response to a question in the Lok Sabha reveal that 65% of Assam’s population, or about 21 million people, is drinking arsenic-contaminated water, while it’s 60% in Bihar and 44% in West Bengal. In terms of absolute numbers, however, Uttar Pradesh has the largest number of people, over 70 million, exposed to arsenic-contaminated water.

How did we get to these numbers? The response to the question contained a list of the 153 districts. We then got the population figures for each district from the census. The census also gives details of the proportion of households in each district that depend on different sources of water for drinking. Hence, we took only those households that are dependent on groundwater sources like wells, tubewells and hand pumps. The population figures were then adjusted for 2016 based on the census’s own projections for states.

The World Health Organisation has warned that longterm intake of such water leads to arsenic poisoning or arsenicosis, with cancer of skin, bladder, kidney or lung, or diseases of skin (colour changes, and hard patches on palms and soles), or blood vessels of legs and feet. Fresh evidence indicates a possible association between intakeof contaminated water and onset of diabetes, hypertension and reproductive disorders, states a WHO document.

States like Maharashtra, Kerala, Uttarakhand, Goa, Tripura and Arunachal have not reported arsenic contamination in groundwater in any district. Odisha and Rajasthan are among the least affected states, with just one district in each having high arsenic levels in groundwater.

WHO’s guideline value for acceptable levels of arsenic in drinking water is0.01mg/litre. In these 153 districts, the arsenic level in groundwater is above this benchmark. For India, the WHO has said that, in the absence of an alternative source of water, arsenic of 0.05 mg/l could be treated as a permissible level. How many districts are above even thislevel? The answer given in Parliament unfortunately does not have that information.

Where does this arsenic come from? The main source in drinking water is arsenicrich rocks through which the water filters. It may also occur because of mining or industrial activities. Drinking the water, crops irrigated with it, and food prepared with contaminated water are the sources of exposure. Fish, shellfish, meat, poultry, dairy products and cereals could also be dietary sourcesof arsenic.

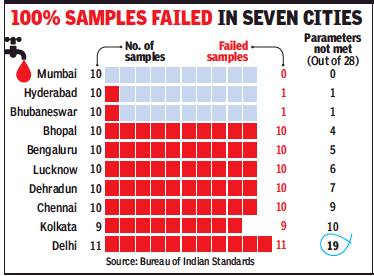

Quality

2019: Mumbai best

Nov 16, 2019: The Times of India

Metro cities of Delhi, Kolkata and Chennai failed in almost 10 out of 11 quality parameters

Testing was conducted to check Organoleptic and physical parameters and know the chemical and toxic substances and bacteriological quality besides virological and biological parameters

NEW DELHI: Mumbai residents need not buy reverse osmosis (RO) water purifiers as a study by the Union consumer affairs ministry has found samples of tap water collected from the financial capital compliant with the Indian standards for drinking water, according to a report.

However, other metro cities of Delhi, Kolkata and Chennai failed in almost 10 out of 11 quality parameters tested by the Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS) which is under the aegis of the consumer affairs ministry.

Similarly, samples drawn from 17 other state capitals were not as per the specification 'Indian Standard (IS)-10500:2012' for drinking water. Releasing the second phase study, consumer affairs minister Ram Vilas Paswan said, "Out of 20 state capitals, all the 10 samples of piped water drawn from Mumbai were found to comply with all 11 parameters, while other cities are failing in one or more."

The solution to this problem is to make compliance of quality standards for piped water mandatory across the country. The ministry has written to state governments in this regard, he told reporters.

"Stringent actions cannot be taken as the quality standards for piped water at present are not mandatory. Once it becomes, we can take actions," Paswan added.

In the first phase, the BIS had found all the 11 samples drawn from Delhi did not comply with the quality norm and the piped water was not safe for drinking purpose, he added.

Testing was conducted to check Organoleptic and physical parameters and know the chemical and toxic substances and bacteriological quality besides virological and biological parameters.

As per the latest study, one or more samples did not comply with the requirements of the IS in the cities of Hyderabad, Bhubaneswar, Ranchi, Raipur, Amravati and Shimla.

For instance, the sample in Hyderabad failed in one parameter 'phenolic compounds' and Bhubaneswar in 'Chloramines', while Chandigarh in two parameters 'Aluminium and Coliform'.

"None of the samples drawn from 13 of the state capitals - Chandigarh, Guwahati, Bengaluru, Gandhinagar, Lucknow, Jammu, Jaipur, Dehradun, Chennai, Kolkata - complied with the requirements of the IS," he said.

In Chennai, all 10 samples failed in nine parameters like turbidity, odour, total hardness, chloride, fluoride, Ammonia, Boron and Coliform, while all nine samples in Kolkata failed in 10 quality parameters, the study showed.

In the third phase, BIS Director-General Pramod Kumar Tiwari said, samples from the capital cities of northeastern states and from 100 smart cities will be tested and their results are expected by January 15, 2020.

In the fourth phase, it is proposed to test samples from all the district headquarters of the country and the results are expected by August 15, 2020, he added.

Details

Dipak Dash, Nov 17, 2019: The Times of India

From: Dipak Dash, Nov 17, 2019: The Times of India

Tap water in Mumbai is the safest for drinking while Delhi’s water is the worst among 21 big cities, according to a report based on sample tests done by Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS). Of greater concern is the fact that

all the samples of tap water taken from 14 out of 21 cities failed to meet one or more safety parameters during tests carried out in laboratories.

With Chandigarh, Gandhinagar, Patna, Bengaluru, Jammu, Lucknow, Chennai and Dehradun recording below-par performance, the first-of-its-kind report has exposed the failure of agencies across cities to provide safe drinking water — a basic right for living. The samples were tested on 28 parameters as prescribed for drinking water standards of BIS notified in 2012.

Releasing the report, consumer affairs minister Ram Vilas Paswan said, “We have been working to provide people’s with their fundamental right to safe drinking water. This issue should not be politicised.” Samples picked from the minister’s house and office in Delhi were among those that failed to meet norms on 19 parameters.

According to the test findings, only one of the samples in Hyderabad and Bhubaneswar failed, and the two cities were ranked second in the list followed by Ranchi and Raipur.

Solutions, success stories

Water conservation in Maharashtra

How water conservation is helping farmers turn a profit, June 13, 2018: The Times of India

From: How water conservation is helping farmers turn a profit, June 13, 2018: The Times of India

As the Centre figures out ways to achieve its target of doubling farmers’ income by 2022, farmers in some villages have already multiplied their income by conserving every drop of water and making agriculture a profit-making venture, says Radheshyam Jadhav in the fourth of the series for TOI’s Water Positive campaign

In the last 25 years, farmers in Hiware Bazar, a tiny village in the arid zone of Maharashtra, have increased their income by an estimated 38 times. But it’s not a miracle, insists village sarpanch Popatrao Pawar, who says the village faced a severe water crisis earlier. The village gets 200-300mm rainfall annually and farmers would migrate in search of work during the summer.

Inspired by Ralegan Siddhi’s water conservation work, Pawar and other villagers started water conservation, rainwater harvesting and watershed management initiatives in the 1990s. Villagers vowed not to let a single drop of rainwater flow out of the village. But this wasn’t enough considering the scanty rainfall. So, they changed cropping patterns and resolved to stop growing the water-guzzling sugarcane, opting for vegetables, pulses, flowers and fruit cultivation.

The villagers meet every December 31 to review water availability and decide the crops to grow. Hiware Bazar, perhaps, is the country’s only village with a water budget. If there is a deficit, farmers take a collective break from farming. But this does not affect their earnings, says Pawar, adding the farmers have a strong dairy business, producing 4,000 litres of milk daily.

Villagers made farming a profitable venture and no family lives below the poverty line. In the last 25 years, Hiware Bazar has not called for a water tanker and over 42 families that had left the village returned. Groundwater is now available at just 20-40 ft in Hiware Bazar while surrounding villages must dig 300-400 ft.

Villagers of Kadwanchi located in the drought-prone Marathwada region in Maharashtra have multiplied their income through watershed management since 1995. They undertake strict water and soil conservation and dig farm ponds to save rainwater and turned to grape cultivation using drip irrigation. A survey, by the central research institute of dryland agriculture, noted average annual incomes of farmers in the village increased from Rs 40,000 in 1996 to Rs 3.2 lakh in 2012, a 700% rise.

It took farmers in Julwaniya Chota in Madhya Pradesh three years to double their income while some villages in Andhra Pradesh increased their income 2-3 times in the last few years according to research by Delhi-based Centre for Science and Environment (CSE). These villages used simple traditional wisdom, the CSE report said, adding that every village can meet its water needs by capturing enough rainwater to meet drinking and cooking needs.

Lapodia, a village of 200 households in Rajasthan, has opted for a model of square dykes to trap rain water. Families here earn sufficiently just by selling milk. Eklava village in Gujarat has collected rainwater over the past 12 years — every house has an underground water tank built near the house to store rainwater that is used for drinking and cooking purposes throughout the year.

These villages represent a new polarization India is going through, states the CSE — those who harvest water and those who don’t.

Villagers made farming a profitable venture and no family lives below the poverty line. In the last 25 years, Hiware Bazar has not called for a water tanker and over 42 families that had left the village returned

The extent of the problem; future projections

2050, as seen in 2018: I

Water Stressed India May Not Be Able To Meet Future Demand, June 2, 2018: The Times of India

From: Water Stressed India May Not Be Able To Meet Future Demand, June 2, 2018: The Times of India

Experts say community-driven, nature-based solutions are the mantra to correct India’s grim water situation, reports Radheshyam Jadhav in the first of a series for the second edition of TOI’s Water Positive campaign

More than 60-70% of India is vulnerable to drought and one-third of the country’s districts have faced more than four droughts in the past decade even as the number of drought-prone areas increased by 57% since 1997.

Not only that: There are about five million springs across India, nearly 3 million in the Himalayan region alone, which are facing the threat of drying up due to increasing water demand, changing land use patterns, and ecological degradation.

Experts stress that sustainability of groundwater must be the focus of policy, programmes and projects to mitigate this situation as India is the world’s largest user of groundwater, which provides 80% of the country’s drinking water needs and supplies nearly twothirds of its irrigation water. Over the last four decades, around 84% of the total addition to irrigation has come from groundwater.