The Indus Valley Civilisation

(→The Indus Valley Civilisation: In brief) |

(→Climate change drove Harappans away) |

||

| (5 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 300: | Line 300: | ||

These displaced people gradually migrated towards the Ganga-Yamuna valley towards eastern and central UP; Bihar and Bengal in the east; MP, south of Vindhyachal and south Gujarat in the south, Gupta added. | These displaced people gradually migrated towards the Ganga-Yamuna valley towards eastern and central UP; Bihar and Bengal in the east; MP, south of Vindhyachal and south Gujarat in the south, Gupta added. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Climate change drove Harappans away== | ||

| + | [https://epaper.timesgroup.com/Olive/ODN/TimesOfIndia/shared/ShowArticle.aspx?doc=TOIDEL%2F2018%2F11%2F16&entity=Ar02117&sk=A804BE57&mode=text Climate change drove Harappans away, November 16, 2018: ''The Times of India''] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File: TOO MANY DRY DAYS- The Indus Valley civilisation.jpg|TOO MANY DRY DAYS- The Indus Valley civilisation <br/> From: [https://epaper.timesgroup.com/Olive/ODN/TimesOfIndia/shared/ShowArticle.aspx?doc=TOIDEL%2F2018%2F11%2F16&entity=Ar02117&sk=A804BE57&mode=text Climate change drove Harappans away, November 16, 2018: ''The Times of India'']|frame|500px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''Shift In Rainfall Patterns Made Agriculture Difficult, Hit Urban Lifestyle: Experts'' | ||

| + | |||

| + | A shift in temperatures and weather patterns over the Indus valley starting about 2500 BC may have driven the Harappans to resettle far away from the floodplains of the Indus, a study has found. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Over 4,000 years ago, the Harappa culture thrived in the Indus River Valley of what is now modern Pakistan and northwestern India, said researchers from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) in the US. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Yet by 1800 BC, this advanced culture had abandoned their cities, moving instead to smaller villages in the Himalayan foothills. Beginning in roughly 2500 BC, a shift in temperatures and weather patterns over the Indus valley caused summer monsoon rains to gradually dry up, making agriculture difficult or impossible near Harappan cities, said Liviu Giosan, a geologist at WHOI. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “Although fickle summer monsoons made agriculture difficult along the Indus, up in the foothills, moisture and rain would come more regularly,” said Giosan, lead author of the study published in ‘Climate of the Past’. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “As winter storms from the Mediterranean hit the Himalayas, they created rain on the Pakistan side, and fed little streams there,” said Glosan. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “Compared to the floods from monsoons that the Harappans were used to seeing in the Indus, it would have been relatively little water, but at least it would have been reliable”. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Evidence for this shift in seasonal rainfall — and the Harappans’ switch from relying on Indus floods to rains near the Himalaya for water crops — is difficult to find in soil samples. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “We don’t know whether Harappan caravans moved toward the foothills in a matter of months or this massive migration took place over centuries. What we do know is that when it concluded, their urban way of life ended,” Giosan said. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The rains in the foothills seem to have been enough to hold the rural Harappans over for the next millennium, but even those would eventually dry up, likely contributing to their ultimate demise. “We can’t say that they disappeared entirely due to climate — at the same time, the Indo-Aryan culture was arriving in the region with Iron Age tools and horses and carts. But it’s very likely that the winter monsoon played a role,” Giosan said. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Monsoon shift doomed Indus civilisation: Study, 2024== | ||

| + | [https://epaper.indiatimes.com/article-share?article=11_09_2024_012_006_cap_TOI Sep 11, 2024: ''The Times of India''] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Pune : A study by researchers at Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology (IITM) has revealed that an interplay of climate factors, strikingly similar to those affecting modern-day monsoons, likely led to the collapse of the Indus Valley civilisation over 4,000 years ago through long droughts, reports Neha Madaan.

| ||

| + | |||

| + | Analysing ancient cave formations (speleothems) from Gupteswar and Kadapa caves in south India, the study found how reduced solar radiation, El Niño, southward migration of Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ), and a negative phase of Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) collectively weakened the monsoon, triggering the downfall of the ancient civilisation. The study has been published in Quaternary International journal. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

Indus Valley civilisation included major urban cen- tres like Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro, along with settlements such as Dholavira, Lothal, and Rakhigarhi. The research team analysed cave deposits in peninsular India, uncovering a 7,000-year climate record that provided insights into the region’s past climate variations. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:History|ITHE INDUS VALLEY CIVILISATION | ||

| + | THE INDUS VALLEY CIVILISATION]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Name|ALPHABETTHE INDUS VALLEY CIVILISATION | ||

| + | THE INDUS VALLEY CIVILISATION]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Pakistan|ITHE INDUS VALLEY CIVILISATION | ||

| + | THE INDUS VALLEY CIVILISATION]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | =Environmental factors= | ||

| + | ==Climate, geology, ecological zones== | ||

| + | [https://epaper.timesgroup.com/article-share?article=17_03_2023_022_015_cap_TOI March 17, 2023: ''The Times of India''] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Oxford University historian Peter Frankopan explains the influence of climate and geography on human history in his book ‘The Earth Transformed: An Untold Story’. He gives an overview of it to Sanjiv Shankaran.

| ||

| + | |||

| + | ''' ●Is it accurate to describe your work as an attempt to weave geology and climate into the study of factors which influenced the evolution of human societies? ''' | ||

| + | |||

| + |

Yes; though the aim is to look both at how humans have been influenced not only by climate but also by geography and nature; and how we in turn have shaped the environment we live in – from the rivers to the atmosphere. I am particularly interested in patterns of exchange and in connections generally; but also in ‘globalising history’ so that we do not always keep looking at the same people and same events. Above all, Iwant to understand why we are facing a mass extinction of animals and plants, and to trace the roots of unsustainability that many of our human predecessors worried about. We can see this as early as in the very first Vedic texts.

| ||

| + | |||

| + | ''' ●Does using the natural environment as a focal point to study historical change suggest that accretive processes are more relevant explanations than a single event or year as the pivotal force? ''' | ||

| + | |||

| + |

Yes! The joy of all evidence – whether from texts or single objects that we find on archaeological digs – is that it can help with small pictures as well as big pictures. So there are lots of big themes that I write about in the book, but also individual events. As an example: volcanic eruptions can be closely linked to climatic change, not surprisingly given the mass ejection of debris and gases into the atmosphere. The eruption last year of Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai in Tonga had the force of around 100 simultaneous detonations of theatomic bomb that was dropped on Hiroshima – and sent a plume of ash and dust higher into the atmosphere than any on record. Because it was an underwater volcano, so much water vapourised that it may explain some of the extraordinary climatic conditions of the last twelve months globally. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

''' ●Why were there similarities in ecological zones which supported the earliest urban settlements? '''

| ||

| + | |||

| + | Well, there were some obvious similarities – but also some important differences. The first big cities grew inplaces that could support large populations so some things are obvious: plenty of good soil and above all lots of water. So the Indus Valley, the Nile, Mesopotamia, the Yellow River in China and so on. Population densities grew in all of these as people were able to get reliable quantities of calories; and clearly people living close to each other enjoy more intensive relationships of all kinds. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

On the other hand, as we were reminded in the pandemic, living close to each other allows diseases to spread; so too does living with animals – whether assource of food, as companions, or as commensals (like rats). Urban settlements naturally tend towards other things too: property rights; writing systems; social and economic hierarchies and such. What is interesting, however, is that the Indus Valley Civilisation differs from others because inequality levels were far lower than other locations. The likely answer is because the Indus, unlike the other rivers, changed course often. That meant that the location of the best land changed, sometimes each year. And that meant the structure of the society was different. Fascinating!

| ||

| + | |||

| + | ''' ●Are we entering a phase when for the first time mass extinction can be catalysed by a species and not natural phenomena? ''' | ||

| + | |||

| + |

There are plenty of ways in which a mass extinction might come from other things we do that do not involve emissions, or resources. For example, the lethal capabilities of our weapons system might dramatically change the face and shape of the earth: even a modest contact between nuclear powers will have major climatic and natural consequences that are global, regardless of where a confrontation happens. As a historian, I can promise that the likelihood of a major war in the future is not so much high as certain. And a nuclear war would make recycling redundant. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

What lets me go to sleep, eventually, is to remember that we’ve managed to do OK for decades, centuries even – and if there is one thing humans are good at, it is picking up the pieces after devastating wars, terrible famines and awful suffering, and getting going again. Greek historian Polybius wrote almost two thousand years ago, “such disasters, tradition tells us, have often befallen mankind and must reasonably be expected to recur. ” No matter how bad things seemed, however, the human population would recover and renew “as if from seeds”. That’s a good way of looking at it! | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | =International connections= | ||

| + | ==Links with Peru?== | ||

| + | [https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/Harrapa-Peruvian-civilisations-linked/articleshow/1797870.cms Prashant Rupera, Harrapa, Peruvian civilisations linked?, July 24, 2006: ''The Times of India''] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Did the Harappan civilisation have a Peruvian link? Researchers working in Kutch are excited over a ‘mystery sign’ found on a hill in Khavda region which, they feel, may usher in a new dimension in the study of Harappan history. | ||

| + | It was a group of experts from the MS University’s geology department that stumbled upon this ‘mysterious’ sign — VI — on a 150-metre-long hill. This, they say, could prove to be a crucial link to find a connection between the two great civilisations — Peruvian and Harappan. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “The sign is unique and resembles the mysterious symbols seen in the ruins in Peru, where such signs can be located on large farms or on the hill-side. We have also recovered ruins of an ancient fort on the top of the hill,” says RV Karanth of MSU’s geology department. Karanth is now compiling a paper on the ‘mystery sign’, to be sent to the department of science and technology at the Centre. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “There are two possibilities for the way the sign was created — natural or manmade. The natural factor seems unlikely as a tectonic movement or rock formation would have created parallel lines. Here we can see a distinct V,” says Karanth. | ||

| + | |||

| + | He also refers to a study by a German mathematician Maria Reiche, who’s work — ‘Enigmatic messages of the Nazcas’ — on the signs in southern Peru, mentions a sign similar to the one spotted in Kutch. “There does seem to be a distinct connection. We need the help of the Archaeological Survey of India to carry out further studies to establish this link by studying signs used by the Peruvian civilisation,” says Karanth. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Kutch region, which is home to famous Harappan sites like the Dholavira, Kuran, Surkotda and Kanmer, has thrown up at least half a dozen sites, with agencies like the ISRO and ASI carrying out individual projects. MSU’s team came across ancient pottery, carnelian fragments and sun-dried bricks in Luna apart from another location near Bela island. | ||

| + | Download The Times of India News App for Latest India News. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:History|ITHE INDUS VALLEY CIVILISATION | ||

| + | THE INDUS VALLEY CIVILISATION]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Name|ALPHABETTHE INDUS VALLEY CIVILISATION | ||

| + | THE INDUS VALLEY CIVILISATION]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Pakistan|ITHE INDUS VALLEY CIVILISATION | ||

| + | THE INDUS VALLEY CIVILISATION]] | ||

=See also= | =See also= | ||

| Line 305: | Line 398: | ||

[[The Indus Valley Civilisation]] | [[The Indus Valley Civilisation]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[The Indus Valley Civilisation: script]] | ||

[[The Vedic Civilisation I]] | [[The Vedic Civilisation I]] | ||

| Line 311: | Line 406: | ||

[[The Vedic Civilisation III]] | [[The Vedic Civilisation III]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Rakhigarhi]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:History|I | ||

| + | THE INDUS VALLEY CIVILISATION]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Name|ALPHABET | ||

| + | THE INDUS VALLEY CIVILISATION]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Pakistan|I | ||

| + | THE INDUS VALLEY CIVILISATION]] | ||

Latest revision as of 21:07, 26 December 2024

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Contents

|

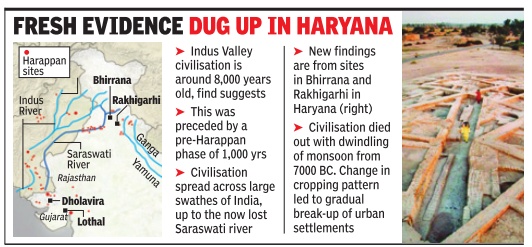

[edit] Originated around 6000 BC

The Times of India, May 29 2016

Indus era 8,000 years old, not 5,500

Jhimli Mukherjeepandey

It may be time to rewrite history textbooks. Scientists from IIT-Kharagpur and the Archaeological Survey of India have uncovered evidence that the Indus Valley Civilisation is at least 2,500 years older than believed, and a pre-Harappan civilisation existed for at least 1,000 years before it.

The discovery, published in the `Nature' journal on May 25, 2016, the `Nature' journal on May 25, may force a global rethink on the timelines of the so-called `cradles of civilisation'. So far, it was believed that the Indus Valley settlements date back 5,500 years. The scientists also believe they know why the civilisation ended around 3,000 ye ars ago -climate change.

“We have recovered perhaps the oldest pottery from the civilisation. We used a technique called `optically stimulated luminescence' to date pottery shards of the Early Mature Harappan time to nearly 6,000 years ago and the cultural levels of pre-Harappan Hakra phase as far back as 8,000 years,“ said Anindya Sarkar, head of the department of geology and geophysics at IIT-Kharagpur.“We unearthed evidence of different cultural levels that mark the progress of the civilisation. In the earliest stages people did not know how to build houses and dug pits in the ground in which they lived.Then, there is evidence of crude pottery and ornaments made by hand. In the later stages, more sophistication is seen -the jewellery is fire-baked,“ Sarkar added.

The team had set out to prove that the civilisation proliferated to other Indian sites like Bhirrana and Rakhigarhi in Haryana, apart from the known locations of Harappa and Mohenjo Daro in Pakistan and Lothal, Dholavira and Kalibangan in India. They took their dig to an unexplored site, Bhir rana -and ended up unearthing something much bigger. The excavation also yielded large quantities of animal remains like bones, teeth, horn cores of cow, goat, deer and antelope, which were put through Carbon 14 analysis to decipher antiquity and the climatic conditions in which the civilisation flourished, said Arati Deshpande Mukherjee of Deccan College, which helped analyse the finds along with Physical Research Laboratory , Ahmedabad.

The researchers believe that the Indus Valley Civilisation spread over a vast expanse of India -stretching to the banks of the now “lost“ Saraswati river or the Ghaggar-Hakra river -but this has not been studied enough because what we know so far is based on British excavations. “At the excavation sites, we saw preservation of all cultural levels right from the pre-Indus Valley Civilisation phase (9,000-8,000 years ago) through what we have categorised as Early Harappan (8,000-7,000 years ago) to the Mature Harappan times,“ said Sarkar.

The late Harappan phase witnessed large-scale de-urbanisation, drop in population, abandonment of established settlements, violence and even the disappearance of the Harappan script, the researchers say . The study re vealed that monsoon started weakening 7,000 years ago but, surprisingly , the civilisation did not disappear.

The Indus Valley people were very resolute and flexible and continued to evolve even in the face of declining monsoon. The people shifted their crop patterns from large-grained cereals like wheat and barley during the early part of intensified monsoon to drought-resistant species like rice in the latter part. As the yield diminished, the organised large storage system of the Mature Harappan period gave way to more individual household-based crop processing and storage systems that acted as a catalyst for the de-urbanisation of the civilisation rather than an abrupt collapse, they say .

[edit] Background

[edit] Briefly

In the 1920s, a huge discovery in South Asia proved that Egypt and Mesopotamia were not the only "early civilizations." In the vast Indus River plains (located in what is today Pakistan and western India), under layers of land and mounds of dirt, archaeologists discovered the remains of a 4,600 year-old city. A thriving, urban civilization had existed at the same time as Egyptian and Mesopotamian states — in an area twice each of their sizes.

The people of this Indus Valley civilization did not build massive monuments like their contemporaries, nor did they bury riches among their dead in golden tombs. There were no mummies, no emperors, and no violent wars or bloody battles in their territory.

Remarkably, the lack of all these is what makes the Indus Valley civilization so exciting and unique. While others civilizations were devoting huge amounts of time and resources to the rich, the supernatural, and the dead, Indus Valley inhabitants were taking a practical approach to supporting the common, secular, living people. Sure, they believed in an afterlife and employed a system of social divisions. But they also believed resources were more valuable in circulation among the living than on display or buried underground.

The "Great Bath" of Mohenjo-Daro is the earliest known public water tank of the ancient world. Most scholars believe that this tank would have been used in conjunction with religious ceremonies.

Amazingly, the Indus Valley civilization appears to have been a peaceful one. Very few weapons have been found and no evidence of an army has been discovered.

Excavated human bones reveal no signs of violence, and building remains show no indication of battle. All evidence points to a preference for peace and success in achieving it.

So how did such a practical and peaceful civilization become so successful?

[edit] The Twin Cities

Seals such as these were used by merchants in the Harappan civilization. Many experts believe that they signified names. The ruins of two ancient cities, Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro (both in modern-day Pakistan), and the remnants of many other settlements, have revealed great clues to this mystery. Harappa was, in fact, such a rich discovery that the Indus Valley Civilization is also called the Harappan civilization.

The first artifact uncovered in Harappa was a unique stone seal carved with a unicorn and an inscription. Similar seals with different animal symbols and writings have since been found throughout the region. Although the writing has not yet been deciphered, the evidence suggests they belonged to the same language system. Apparently, Mesopotamia's cuneiform system had some competition in the race for the world's first script.

The discovery of the seals prompted archaeologists to dig further. Amazing urban architecture was soon uncovered across the valley and into the western plains. The findings clearly show that Harappan societies were well organized and very sanitary.

This copy of the Rig Veda was written after the Vedic Age. The Aryans had no form of writing at the time they invaded India. Instead, these religious scripts would have been memorized and passed down orally by Brahman priests. For protection from seasonal floods and polluted waters, the settlements were built on giant platforms and elevated grounds. Upon these foundations, networks of streets were laid out in neat patterns of straight lines and right angles. The buildings along the roads were all constructed of bricks that were uniform in size.

The brick houses of all city dwellers were equipped with bathing areas supplied with water from neighborhood wells. Sophisticated drainage systems throughout the city carried dirty water and sewage outside of living spaces. Even the smallest houses on the edges of the towns were connected to the systems — cleanliness was obviously of utmost importance.

[edit] The Fall of Harappan Culture

No doubt, these cities were engineering masterpieces of their time. The remains of their walls yield clues about the culture that thrived in the Indus Valley. Clay figurines of goddesses, for example, are proof that religion was important. Toys and games show that even in 3000 B.C.E., kids — and maybe even adults — liked to play. Pottery, textiles, and beads are evidence of skilled craftsmanship and thriving trade.

It was this intensive devotion to craftsmanship and trade that allowed the Harappan culture to spread widely and prosper greatly. Each time goods were traded or neighbors entered the gates of the cities to barter, Indus culture was spread.

Eventually, though, around 1900 B.C.E, this prosperity came to an end. The integrated cultural network collapsed, and the civilization became fragmented into smaller regional cultures. Trade, writing, and seals all but disappeared from the area.

Because there is little evidence of any type of invasion though, numerous historians claim that it was an environmental disaster that led to the civilization's demise. They argue that changing river patterns disrupted the farming and trading systems and eventually led to irreparable flooding.

[edit] The Indus Valley Civilisation: the essentials

TIME CHECK: Indus Valley Civilisation

By Mubarak Ali

This originally appeared as a seven-part article in Dawn in August-Sept 2008. Inputs by other authers have been inter-woven into Dr Ali's article but he is the author of all sections not credited to someone else.

[edit] Discovery of Mohenjodaro

The second important city which was excavated in 1922-23 was Mohenjodaro. The name of the city is pronounced either as Mohenjodaro meaning ‘the mound of the dead’ or Mohenjodaro attributing it to Mohan tribe of Sindh.

There are also differences among historians about the nomenclature of the civilisation. Some experts call it ‘Harappan Civilisation’ because Harappa was the first site which was excavated. However, after the excavation of more sites, it was named as the ‘Indus Valley Civilisation’.

This Bronze Age civilisation is not as old as Mesopotamian or Egyptian civilisations; the archaeologists believe it to have been established around 2,500 BC. Indus Valley Civilisation, being a newly-discovered civilisation, is the centre of attention for experts who want to excavate its ancient sites to discover new findings. So far, they have unearthed 500 sites ranging from 2500 to 1900 BC. These sites were found in Balochistan, Sindh, Punjab, Haryana, Gujarat, Rajasthan and western Utter Pardesh. It shows the expansion of the civilisation in the Indian subcontinent.

[edit] Expansion of Indus Valley Civilisation

History tells us that a kingdom, after gaining its political power, united different groups of people and linked their social, cultural, and economic interests with each other. However, experts are still confused as they haven’t found any trace of any empire or political power in the Indus Valley Civilisation. Therefore, the question arises about the reason behind the expansion of the Indus Valley Civilisation to such a vast area and having varied groups of people living together. How such a vast area was administered by a single system? They tried to find out the causes but, of course, their responses are based on speculations. Some suggested that perhaps all of them spoke the same language which created in them an affinity. Some argued that perhaps trade and commerce linked them; or perhaps some internal or external danger forced them to depend on each other. However, without evidence, it is difficult to reach any conclusion.

[edit] City

History tells us that civilisations originate in cities; therefore, if a civilisation has many cities, it means it’s a growing and expanding one. Cities are important because they reflect different shades of culture and by studying them we get to know about the lifestyles of people and their activities.

Indus Valley Civilisation is different from Mesopotamian or Chinese civilisations because like them it had no ‘city republics’. On the other hand, its cities were linked with each other very closely. Another point of difference is that like Mesopotamia and Egypt, Indus Valley Civilisation had no magnificent temples and tombs. Even its public buildings were built in simple style. Moreover, there were no high-rise buildings. As stone was not available in this area, these buildings were constructed with bricks. They were either sunburnt or baked in fire. Special care was taken to maintain proportion in their size. These bricks are so strong that the buildings made from them are still standing in spite of the changing weather conditions.

[edit] Mohenjodaro and Harappa

After the excavation Mohenjodaro came out in its original form unlike other cities of the Indus Valley Civilization. It shows that the city was built systematically after proper planning. Analyzing the structure of the city, one can also calculate the number of its inhabitants. One part of the city was situated on a mound which was the residential area of the upper classes. Lower classes had their quarters on the outskirts of the city.

The main roads of the city were wide, straight and well paved. Side streets were integrated with the main road which facilitated the commuters to move around freely. Sanitation system was well organised and all drains were covered. There was a ‘Great Bath’ in the city, which was, without any doubt, the earliest public water tank in the ancient world. After its excavation, archaeologists found a series of steps which go inside the tank. Its floor is made of burnt bricks and inner walls are built in such a way that seepage was not possible. Around the tank are small rooms which according to experts were used for performing religious rituals.

There was a store to preserve grain. It is assumed that the reserved grain was either utilised in case of famine or drought or for trade. There was also a ‘Great Hall’ in the city, which might have been used for political, social or religious meetings. There were about 2,000 to 3,000 houses and 700 wells in the city. It is estimated that the population of the city was 85,000.

The city of Harappa was also constructed the same way. It was surrounded by walls. As the city could not retain its original shape, experts assume that the city had a bath tank, public hall, and roads, well planned houses and wells just like Mohenjodaro. Its population is assumed to be 35,000.

Keeping in view the planning of these ancient cities, one can safely say that the people of Indus Valley were cleanliness-conscious. The existence of bathrooms in every house shows that they were used to take bath and also kept their houses and streets clean.

[edit] Houses

The ruins of the cities depict the construction of their houses. The houses were made of burnt bricks and built on both sides of roads. Generally, the houses were double storeyed. The rooms were built on the side of the courtyard and were windowless. Food was cooked and eaten in the courtyard. Every house had a bathroom and a well for water supply. House drainpipe poured its waste water into the street drain. All street drains were covered. Their houses were built not only for living and meeting social requirements but also to protect them from the hot climate.

[edit] Kunal

SUKHBIR SIWACH, December 29, 2017: The Indian Express

From: SUKHBIR SIWACH, December 29, 2017: The Indian Express

Kunal is a pre-Harappan or early Harappan site, and is said to the oldest site so far found in Haryana.

[edit] Bead workshop excavated/ 2017

SUKHBIR SIWACH, December 29, 2017: The Indian Express

Findings at the pre-Harappan archaeological excavation site in Kunal have pointed to the existence of a steatite bead-making workshop at the location, and support the theory that this was an early trading centre with skilled artisans and outside links possibly stretching to as far as Mesopotamia in West Asia.

Scores of beads were found at the excavation site earlier in 2017. Kunal is a pre-Harappan or early Harappan site, and is said to the oldest site so far found in Haryana. “Earlier, it was believed that the manufactured beads were brought to Kunal from other places but now we have enough evidences including discovery of an article probably used for modifications of the raw mineral which suggest that these were manufactured here,” said Dr BR Mani, Director General of the National Museum while speaking to The Indian Express.

According to Mani, the beads found from Kunal site belong to 3,000 BC to 2,500 BC. The excavation of the ancient site at Kunal was conducted jointly by Haryana Archaeology Department, Indian Archaeological Society, New Delhi and the National Museum, New Delhi during from February to April. “The study suggests that Kunal was a Centre of trade during the era having probable trade links up to West Asia also. The raw material for the said workshop or industry was brought to Kunal most probably from Rajasthan. It is possible that the manufactured beads were transported to other parts during that era,” said an official of the Haryana Archaeology Department.

A dig in the 1990s had yielded a copper smelting zone. The metal is believed to have come from Khetri in Rajasthan, the nearest place with copper deposits. On the basis of the findings of the Haryana archaeologists, National Museum and Indian Archaeological Society, the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) has given the go ahead for another phase of the excavation at Kunal village for the season of 2017-18.

During the excavation carried out in February to April this year, large number of micro beads were found which is evidence of very skilled manpower during this era of civilization. The archaeologists believe that raw material for beads came from present day Rajasthan and Gujarat.”Steatite beads of different colours and some of them with hair-size thickness were also found. Evidence of copper smelting zone was already found here. Minerals like copper, gold and even silver, material for bead such as carnelians, agate, jasper, lapislazuli were believed to be brought from other states. We have found amazing paintings and designs on ceramics,” said an archaeologist associated with the study.

“Shell rings have already been discovered. During the old times, sophisticated or high class people opted for precious stones, carnelians, agate, jasper, lapislazuli while the common man might have used terracotta ornaments, including its bangles,” added the archaeologist. The experts are also trying to understand food habits of the people and environment during the oldest era of the civilization in this region.

Preliminary study has suggested that people of the era had even brought a water channel to this region which had low density flow of the water. “It was a fertile area. We have found evidences of multi cropping like of rice, ragi and oat here,” said an archeologist.

[edit] Instruments and Weapons

In the bronze civilisations, the tools and weapons that were used were made of bronze; these were more durable than the ones made of stone used in the stone civilisations. These weapons and equipment included knives, axes, pins, needles and saw. The sharp points of spears and arrows were also made of bronze that made hunting easier than before.

As the need for weapons and different instruments grew, a class of artisans who were expert in making such instruments also emerged. The job of these craftsmen was to manufacture different tools. They not only used bronze to make weapons and instruments but also utilised stones, clay, bones of animals, gold and silver for this purpose. Carpenters might have made wooden handles for some weapons. As these wooden handles were not found, it is assumed that they were buried beneath the earth.After excavation, experts found in the Indus Valley various earthen pots such as plates, bowels and cups of different size. These pots were decorated with different colourful designs on their surfaces. Archaeologists also found deities and tablets made of clay.

[edit] Carts and Boats

When people domesticated animals, they used them for different purposes. Animals were yoked in plough for digging the fields and for sowing seeds. The animals were also used to draw two-wheeler carts for transportation of goods. The experts also found four-wheeler carts which provided more space for goods. These carts were also used to take passengers from one place to another.

Besides carts, boats were also used to transport men and goods. The life in Indus Valley was full of energy and the efficient communication system promoted trade and commerce and thus facilitated smooth transportation of people and goods from one place to another.

[edit] Seals

After excavation, archaeologists found a large number of seals from different places. According to the experts, when traders used to transport their goods they put seals on the boxes and baskets in order to prevent stealing. The seals were square in shape, with something written on the top and engravings of some animals such as unicorn, bull, elephant, rhino and zebra at the bottom. Nearly 60 per cent of the seals had unicorn drawn on their lower portions. Some seals also had geometrical designs and sign of swastika. (The swastika is the oldest cross and emblem in the world. It forms a combination of four “Ls” standing for luck, light, love and life.) Despite every possible effort, the writings on the seals could not be deciphered, which is why most of the mysteries linked to the Indus Valley Civilisation have not been unveiled yet.

[edit] Development

[edit] Script

In an attempt to understand any civilisation, script plays an important role; by decoding the scripts, one can comprehend the documents of state that provide information about tax system, distribution of grain, administrative rules and regulations, laws, declarations of rulers on political, social, and economic matters, treaties between two states, contracts with traders and business relationships. It also provides information about art, literature and social and cultural practices of a society.

Script kept on changing in every civilisation. In its earliest form, it was pictographic. Later on it became ideographic in which ideas and thoughts were explained with the help of signs and symbols. The script of Indus Valley contains a number of signs but despite all their efforts experts have not been able to decipher the meaning of these signs. Hence the symbolic script of Indus Valley is still a mystery. Unlike Egypt, experts did not find any source which could help them decode the script of Indus Valley. Consequently, researchers couldn’t get to know about most of the aspects of this civilisation.

[edit] Agriculture

Majority of the population of the Indus Valley consisted of peasants and cultivators. They were the people who cleared the land from forests for cultivation and dug canals for irrigation. They grew a variety of crops including wheat, barley, millet, pulses, pease, rice, mustard and cotton.

Fruits including watermelon, dates and grapes were also cultivated. Besides these, wild fruits were also produced in abundance.

People used a stone slab to grind the wheat. A number of animals were domesticated and used for different tasks. Oxen, cows, unicorns, buffaloes, goats and sheep provided milk and meat; they were also used to drive carts and plough the field.

[edit] Society

The Indus Valley society was divided into different classes based on social status. Difference between the lifestyles of rich and poor could be observed in the residential areas. Rich and privileged had their houses on the upper level of the city. Their houses were spacious and had separate quarters for servants. Poor people lived in the lower part of the city in small houses. The evidence of slavery was also found there.

Majority of the population consisted of peasants and wandering tribes. Peasants lived in villages while wandering tribes lived in forests and kept on moving from one place to another in search of grazing fields for their animals.

In cities there were artisans, priests and scribes. They were identified on the basis of their professions. There was division of labour between men and women. It was the women’s job to grind flour, weave cloth and look after animals. Men engaged in cultivation and hunting. The average age of the people was 30 years. Dead either were buried or burnt. In some cases, the dead body was abandoned in the forest.

In the Indus Valley Civilisation, rulers and nobles had no grand tombs like Egypt. They were buried like others in ordinary graves. As it was the custom to bury all belongings with the dead, the buried items helped researchers to identify the social status of the deceased and at the same time they got to know about the manufacturing process adopted by the artisans to prepare things for daily use.

[edit] Dress

One of the most significant findings from the ruins of Indus Valley Civilisation is a piece of cloth, which indicates that the people of the valley cultivated cotton and were also familiar with the art of weaving and making fabric. Later on, looms were also found, which confirmed the existence of skilled weavers in the society. It is also assumed that women in their spare time — besides other household jobs — weaved cloth. Statues discovered from the ruins depict the clothing of Indus Valley people. Both men and women covered themselves with an unstitched long piece of cloth. Women also used necklace and bangles for adornment. Rich people also put a shawl type garment on their shoulders to distinguish themselves from commoners.

[edit] Jewellery

History reveals that the use of jewellery in any civilisation started only after the discovery of metals. With the discovery of metals, another class of artisans emerged who knew the art of moulding metals into different kinds of ornaments. The ornamental items give an idea about the aesthetic taste of any society. The jewellery found after the excavation of Indus Valley indicates the class difference in the society. Rich people used to wear costly ornaments made of gold, silver or precious stones, while poor people wore jewellery made of cheap metals and inexpensive stones.

The ornaments found from the ruins are made of gold, silver, copper, bronze, shell, ivory, and costly and cheap stones. These include bangles, necklaces, bracelets, rings, earrings, hairpins and anklets. The bangles had different designs engraved on them. The ornaments were worn both by men and women.

[edit] Makeup

Indus Valley, being an advanced society, had people who were beauty conscious and made efforts to look elegant. They were fond of using cosmetics. Experts found many used holders of antimony which was used for eyes. They also found red powder in small shell boxes which was probably used as blusher. Moreover, experts have also found round shaped mirrors.

[edit] Toys

Archaeologists found a number of toys from different sites of Indus Valley which show the love and care of people for their children. The toys symbolise their maturity as they used toys to educate their children besides engaging them in healthy fun activities. Many animal-shaped toys such as elephant, rhino, buffalo, bull, tiger, pig, monkey, goat, sheep and hare were found. They were made of clay, shell, ivory and stones. A toy cart made of clay was also found.

[edit] Sports And Entertainment

There were two types of sports popular among Indus Valley people: outdoor and indoor. Experts found a dice made of clay and stone, which is assumed to be used in gambling or fortune-telling. Interestingly, experts also found pieces like the ones that are used in modern-day chess.

It is also assumed that animal and bird fighting contests also took place in the society. Indus Valley people were also fond of music and dancing. The dancing girl statue found after excavation reveals not only craftsmanship but also their love for dance.

[edit] Ruling classes

The important classes which emerged as powerful in the Indus Valley included landlords, priests, high officials, traders and merchants. Their social status depended on their financial condition and political and social influence in the society. Traders and merchants accumulated wealth as a result of their trade and became rich but politically they were not powerful. Landlords extorted surplus products from the peasants and enjoyed all the luxuries of the time. Priests as spiritual representatives of gods received offerings from people which made them wealthy as well as respectable. Government officials had authority as managers of administration. In any society, when wealth and power combined the ruling classes’ assumed high privileged status.

As no evidence of kingship in the Indus Valley has been found, therefore, it is assumed that the administration was conducted by a council or a committee consisting of influential people. This system continued very successfully for nearly 700 years. During this period nearly 30 generations lived under this system without much change. The administration remained resourceful and efficient. Whenever the need arouse it arranged for the repair of the cities’ walls for protection of inhabitants and managed disposal of solid waste and kept the drainage system in working order.

Though Indus Valley Civilisation was spread over a large area, there is no evidence of the presence of a large army, conquests of other parts of the subcontinent and consequently massacre of vanquished people. Unlike other ancient civilisations, there are no engravings that show war prisoners or war booty as a sign of victory, nor are there any monuments of victory. Though there is evidence that there were weapons, they were not used for the expansion of empire.

Therefore, historians are amazed that how such peaceful people could have such a vast area under their control without wars and conquests.

[edit] Religion

We do not have much information about their religion. Whatever evidence we have shows that they were very much attached to nature because it provided them food, security, safety, and healthy environment. Therefore, their concern was to preserve nature and not to destroy it. They used to pay their respect to and worshiped animals, birds, and trees as their benefactors. This tendency is evident from the seals which experts found which contain their images; especially the image of unicorn is present on a large number of seals which was perhaps regarded as sacred. The seals also have engraving of deities which were worshiped by them. The statue of the priest king found at Mohenjodaro is very elegant and impressive.

During the excavations at Mohenjodaro, the remains of a Great Bath have also been found; it is believed that it was used for religious rituals like for bathing before worship.

[edit] Trade

Society’s overall economic prosperity depends on its commercial activities. Traders not only provided essential items to the people but also items of luxury and comfort. Therefore, in all ancient civilisations, trade and commerce played an important role in their well-being and also connected them with other countries, thus enhancing their vision regarding world affairs.

Indus Valley Civilisation was extended over a vast area including different regions of the Indian subcontinent, that’s why it provided ample opportunities to the traders to build commercial links with far off regions. Besides domestic trade, evidences of foreign trade activities are also found. The traders and merchants played a vital role in the development of the society; they earned wealth and high repute and became a part of the ruling class.

Weighing and measurement instruments have a significant importance in trade. After excavation, experts found out various square-shaped weighing instruments made of stone. But no measuring instrument could be found, though it is assumed that there must be some; for this reason it is difficult to state anything about their measuring system. Besides this, there are many queries about their calculation system, the signs for counting figures and so on. But these questions are still unanswered.

As coin was not invented till then, the traders of Indus Valley adopted barter system. It is assumed by the experts that they might have used seals in place of coins for exchange of commodities, but this can’t be said with certainty.

Generally, trading was carried out by bringing agriculture products from villages to cities and selling them in the markets. Traders were also engaged in foreign deals and exported commodities and manufactured goods to other countries. Exportation of various goods indicates that production was in abundance, which shows the economic prosperity of the society. It also gives us an idea about the expertise of the artisans because their work was in high demand by the foreigners.

Trade was carried out via both land and water. For road transportation, four-wheeler carts were used, while boats were used for transportation via river and sea. These commercial activities reveal that both sea and land routes were safe.

The export items included pottery, grain, raw cotton and cotton fabrics, spices, beads, pearls and antimony. The goods that were imported included a variety of objects made of metal.

The countries which had commercial relations with the Indus Valley traders were Persian Gulf, Central Asia and Mesopotamia. The seals found from the ruins indicate the links of the Indus Valley with these countries.

[edit] Conclusion

The evidences found from the ruins of the Indus Valley indicate that the civilisation was highly developed. The cities of the Indus Valley, which were the centre of commercial, social, and cultural activities, point towards the advancement of the civilisation.

We do not find such a large number of big cities in other ancient civilisations. Cities of the Indus Valley had large number of artisans who were skilled in manufacturing different types of items made of metals, stones and clay. These items were utilised by the city dwellers as well as by the villagers. These objects also reveal the artistic and technical skills of the people.

The significant classes of the society consisted of traders, priests and high officials. Most of the people were peasants but due to the absence of any trace of grand and splendid buildings such as palaces, temples, and tombs, it is assumed that the peasants were not as exploited by the elite class as in other civilisations. Common people were not forced to work without any payment.

No evidence of monarchy or any single authority was found, which indicates that there was no tax extortion. Probably, administrative tasks were handled by the councils consisted of priests and tribal leaders. As members of councils had no state power, common men could not be harassed by the people on the managerial posts.

The language is one of the most important sign of the development of any society. Based on the specimen that we have, we find that the language of the Indus Valley was not fully developed.

It proved that there was not institution of state because we find that in other ancient civilisations where state and its institutions were established, language became an administrative tool. Language was used as a mean to issue different declarations to propagate laws, to register receipt of taxes and to write down contracts. With the help of written statements, various important state documents were also preserved.

Moreover, language also played an important role in the enrichment of the literature. But as the script of the Indus Valley could not be deciphered, we are still unaware of its state documents and commercial contracts. Any single piece of literature was also not found, which indicates the deficiency of the language or non-availability of these sources.

Experts also did not find any trace of calendar. However, sculptures, pottery and other artefacts found after excavation clearly state the artistic skills of the people. Though Indus Valley civilisation was widely spread and centrally connected but this association or the strong bond between the people was not because of any political power. It was either culture or economy that connected the people from each other.

Experts assume that due to the absence of any political power, it can be safely said that people of the Indus Valley were not chaotic and messy; instead they were highly civilised and peaceful people.

[edit] Decline—and disappearance

[edit] ‘900-year drought wiped out Indus civilisation: IIT-Kharagpur’

From: Jhimli Mukherjeepandey 900-year drought wiped out Indus civilisation: IIT-Kgp, April 16, 2018: The Times of India, Courtesy: Sanjay Hadkar

The Indus Valley civilisation was wiped out 4,350 years ago by a 900-year-long drought, scientists at the Indian Institute of Technology in Kharagpur (IIT-Kgp) have found. Evidence gathered during their study also put to rest the widely accepted theory that the said drought lasted for only about 200 years.

The study will be published in the prestigious Quaternary International Journal by Elsevier this month.

Researchers from the geology and geophysics department have been studying the monsoon’s variability for the past 5,000 years and have found that the rains played truant in the northwest Himalayas for 900 long years, drying up the source of water that fed the rivers along which the civilisation thrived. This eventually drove the otherwise hardy inhabitants towards the east and south, where rain conditions were better.

The IIT-Kgp team mapped a 5,000-year monsoon variability in the Tso Moriri Lake in Leh-Ladakh — which too was fed by the same glacial source — and identified periods that had continuous spells of good monsoon as well as phases when it was weak or nil.

“The study revealed that from 2,350 BC (4,350 years ago) till 1,450 BC, the monsoon had a major weakening effect over the zone where the civilisation flourished. A droughtlike situation developed, forcing residents to abandon their settlements in search of greener pastures,” said Anil Kumar Gupta, the lead researcher and a senior faculty of geology at the institute.

These displaced people gradually migrated towards the Ganga-Yamuna valley towards eastern and central UP; Bihar and Bengal in the east; MP, south of Vindhyachal and south Gujarat in the south, Gupta added.

[edit] Climate change drove Harappans away

Climate change drove Harappans away, November 16, 2018: The Times of India

From: Climate change drove Harappans away, November 16, 2018: The Times of India

Shift In Rainfall Patterns Made Agriculture Difficult, Hit Urban Lifestyle: Experts

A shift in temperatures and weather patterns over the Indus valley starting about 2500 BC may have driven the Harappans to resettle far away from the floodplains of the Indus, a study has found.

Over 4,000 years ago, the Harappa culture thrived in the Indus River Valley of what is now modern Pakistan and northwestern India, said researchers from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) in the US.

Yet by 1800 BC, this advanced culture had abandoned their cities, moving instead to smaller villages in the Himalayan foothills. Beginning in roughly 2500 BC, a shift in temperatures and weather patterns over the Indus valley caused summer monsoon rains to gradually dry up, making agriculture difficult or impossible near Harappan cities, said Liviu Giosan, a geologist at WHOI.

“Although fickle summer monsoons made agriculture difficult along the Indus, up in the foothills, moisture and rain would come more regularly,” said Giosan, lead author of the study published in ‘Climate of the Past’.

“As winter storms from the Mediterranean hit the Himalayas, they created rain on the Pakistan side, and fed little streams there,” said Glosan.

“Compared to the floods from monsoons that the Harappans were used to seeing in the Indus, it would have been relatively little water, but at least it would have been reliable”.

Evidence for this shift in seasonal rainfall — and the Harappans’ switch from relying on Indus floods to rains near the Himalaya for water crops — is difficult to find in soil samples.

“We don’t know whether Harappan caravans moved toward the foothills in a matter of months or this massive migration took place over centuries. What we do know is that when it concluded, their urban way of life ended,” Giosan said.

The rains in the foothills seem to have been enough to hold the rural Harappans over for the next millennium, but even those would eventually dry up, likely contributing to their ultimate demise. “We can’t say that they disappeared entirely due to climate — at the same time, the Indo-Aryan culture was arriving in the region with Iron Age tools and horses and carts. But it’s very likely that the winter monsoon played a role,” Giosan said.

[edit] Monsoon shift doomed Indus civilisation: Study, 2024

Sep 11, 2024: The Times of India

Pune : A study by researchers at Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology (IITM) has revealed that an interplay of climate factors, strikingly similar to those affecting modern-day monsoons, likely led to the collapse of the Indus Valley civilisation over 4,000 years ago through long droughts, reports Neha Madaan.

Analysing ancient cave formations (speleothems) from Gupteswar and Kadapa caves in south India, the study found how reduced solar radiation, El Niño, southward migration of Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ), and a negative phase of Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) collectively weakened the monsoon, triggering the downfall of the ancient civilisation. The study has been published in Quaternary International journal.

Indus Valley civilisation included major urban cen- tres like Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro, along with settlements such as Dholavira, Lothal, and Rakhigarhi. The research team analysed cave deposits in peninsular India, uncovering a 7,000-year climate record that provided insights into the region’s past climate variations.

[edit] Environmental factors

[edit] Climate, geology, ecological zones

March 17, 2023: The Times of India

Oxford University historian Peter Frankopan explains the influence of climate and geography on human history in his book ‘The Earth Transformed: An Untold Story’. He gives an overview of it to Sanjiv Shankaran.

●Is it accurate to describe your work as an attempt to weave geology and climate into the study of factors which influenced the evolution of human societies?

Yes; though the aim is to look both at how humans have been influenced not only by climate but also by geography and nature; and how we in turn have shaped the environment we live in – from the rivers to the atmosphere. I am particularly interested in patterns of exchange and in connections generally; but also in ‘globalising history’ so that we do not always keep looking at the same people and same events. Above all, Iwant to understand why we are facing a mass extinction of animals and plants, and to trace the roots of unsustainability that many of our human predecessors worried about. We can see this as early as in the very first Vedic texts.

●Does using the natural environment as a focal point to study historical change suggest that accretive processes are more relevant explanations than a single event or year as the pivotal force?

Yes! The joy of all evidence – whether from texts or single objects that we find on archaeological digs – is that it can help with small pictures as well as big pictures. So there are lots of big themes that I write about in the book, but also individual events. As an example: volcanic eruptions can be closely linked to climatic change, not surprisingly given the mass ejection of debris and gases into the atmosphere. The eruption last year of Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai in Tonga had the force of around 100 simultaneous detonations of theatomic bomb that was dropped on Hiroshima – and sent a plume of ash and dust higher into the atmosphere than any on record. Because it was an underwater volcano, so much water vapourised that it may explain some of the extraordinary climatic conditions of the last twelve months globally.

●Why were there similarities in ecological zones which supported the earliest urban settlements?

Well, there were some obvious similarities – but also some important differences. The first big cities grew inplaces that could support large populations so some things are obvious: plenty of good soil and above all lots of water. So the Indus Valley, the Nile, Mesopotamia, the Yellow River in China and so on. Population densities grew in all of these as people were able to get reliable quantities of calories; and clearly people living close to each other enjoy more intensive relationships of all kinds.

On the other hand, as we were reminded in the pandemic, living close to each other allows diseases to spread; so too does living with animals – whether assource of food, as companions, or as commensals (like rats). Urban settlements naturally tend towards other things too: property rights; writing systems; social and economic hierarchies and such. What is interesting, however, is that the Indus Valley Civilisation differs from others because inequality levels were far lower than other locations. The likely answer is because the Indus, unlike the other rivers, changed course often. That meant that the location of the best land changed, sometimes each year. And that meant the structure of the society was different. Fascinating!

●Are we entering a phase when for the first time mass extinction can be catalysed by a species and not natural phenomena?

There are plenty of ways in which a mass extinction might come from other things we do that do not involve emissions, or resources. For example, the lethal capabilities of our weapons system might dramatically change the face and shape of the earth: even a modest contact between nuclear powers will have major climatic and natural consequences that are global, regardless of where a confrontation happens. As a historian, I can promise that the likelihood of a major war in the future is not so much high as certain. And a nuclear war would make recycling redundant.

What lets me go to sleep, eventually, is to remember that we’ve managed to do OK for decades, centuries even – and if there is one thing humans are good at, it is picking up the pieces after devastating wars, terrible famines and awful suffering, and getting going again. Greek historian Polybius wrote almost two thousand years ago, “such disasters, tradition tells us, have often befallen mankind and must reasonably be expected to recur. ” No matter how bad things seemed, however, the human population would recover and renew “as if from seeds”. That’s a good way of looking at it!

[edit] International connections

[edit] Links with Peru?

Prashant Rupera, Harrapa, Peruvian civilisations linked?, July 24, 2006: The Times of India

Did the Harappan civilisation have a Peruvian link? Researchers working in Kutch are excited over a ‘mystery sign’ found on a hill in Khavda region which, they feel, may usher in a new dimension in the study of Harappan history.

It was a group of experts from the MS University’s geology department that stumbled upon this ‘mysterious’ sign — VI — on a 150-metre-long hill. This, they say, could prove to be a crucial link to find a connection between the two great civilisations — Peruvian and Harappan.

“The sign is unique and resembles the mysterious symbols seen in the ruins in Peru, where such signs can be located on large farms or on the hill-side. We have also recovered ruins of an ancient fort on the top of the hill,” says RV Karanth of MSU’s geology department. Karanth is now compiling a paper on the ‘mystery sign’, to be sent to the department of science and technology at the Centre.

“There are two possibilities for the way the sign was created — natural or manmade. The natural factor seems unlikely as a tectonic movement or rock formation would have created parallel lines. Here we can see a distinct V,” says Karanth.

He also refers to a study by a German mathematician Maria Reiche, who’s work — ‘Enigmatic messages of the Nazcas’ — on the signs in southern Peru, mentions a sign similar to the one spotted in Kutch. “There does seem to be a distinct connection. We need the help of the Archaeological Survey of India to carry out further studies to establish this link by studying signs used by the Peruvian civilisation,” says Karanth.

The Kutch region, which is home to famous Harappan sites like the Dholavira, Kuran, Surkotda and Kanmer, has thrown up at least half a dozen sites, with agencies like the ISRO and ASI carrying out individual projects. MSU’s team came across ancient pottery, carnelian fragments and sun-dried bricks in Luna apart from another location near Bela island. Download The Times of India News App for Latest India News.

[edit] See also

The Indus Valley Civilisation