Economy: India 1

Several sections from this page have been shifted to Economy: India 2 (Ministry data)

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

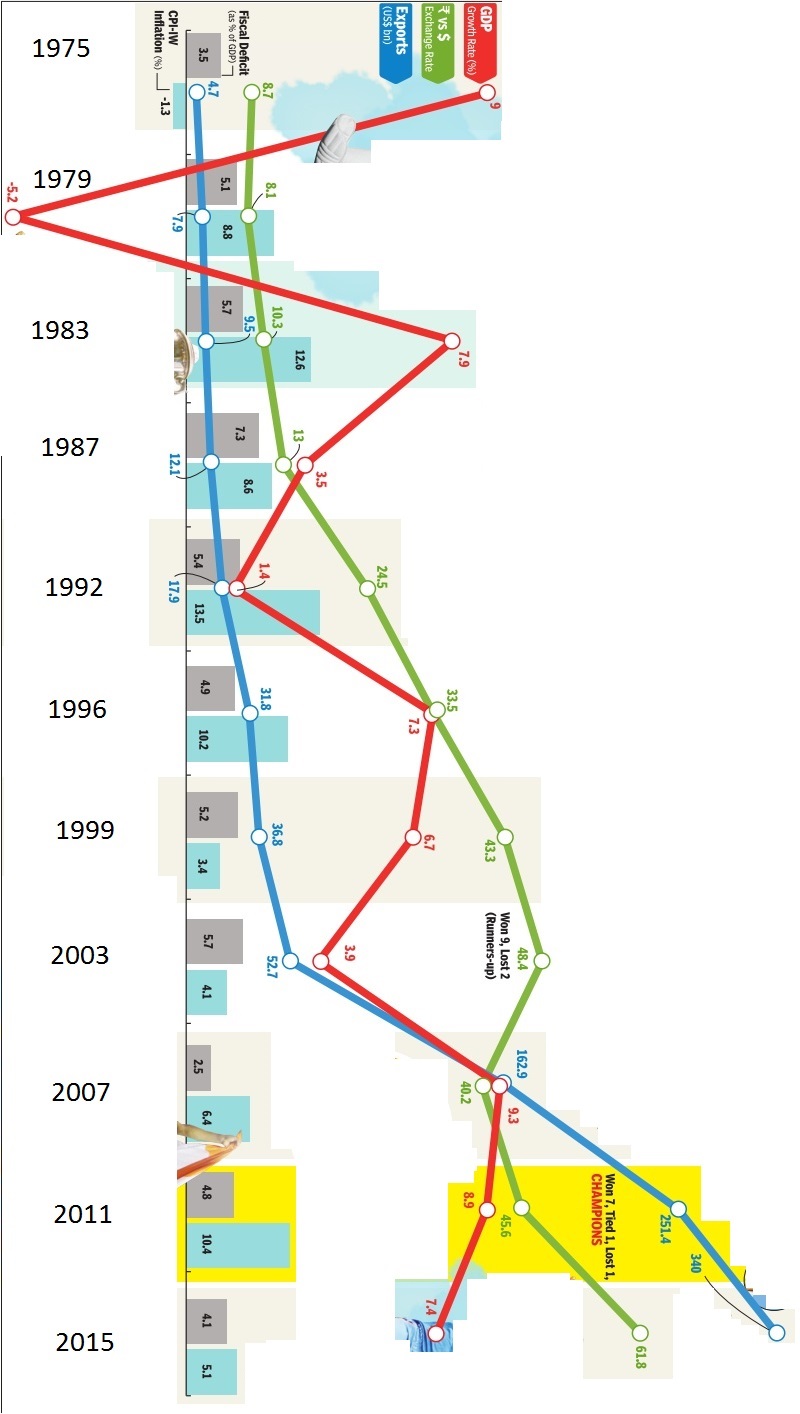

The yearwise position

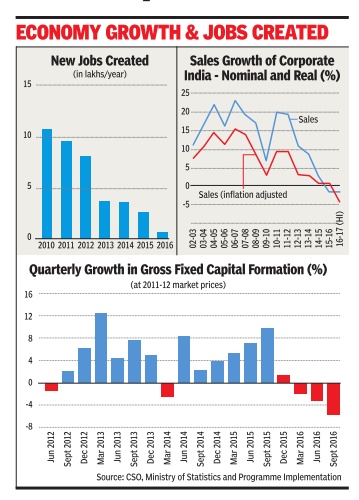

ii) Sales Growth of corporate India-Nominal and Real (%), 2002-17;

iii) Quarterly growth in Gross Fixed Capital Formation (%), Jun 2013- Sept 2016; The Times of India, January 31, 2017

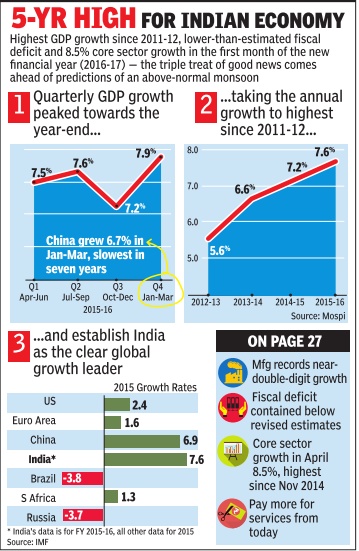

2012-16: fastest growth in 5 years

The Times of India, Jun 01 2016

Eco grows fastest in 5 years at 7.6%

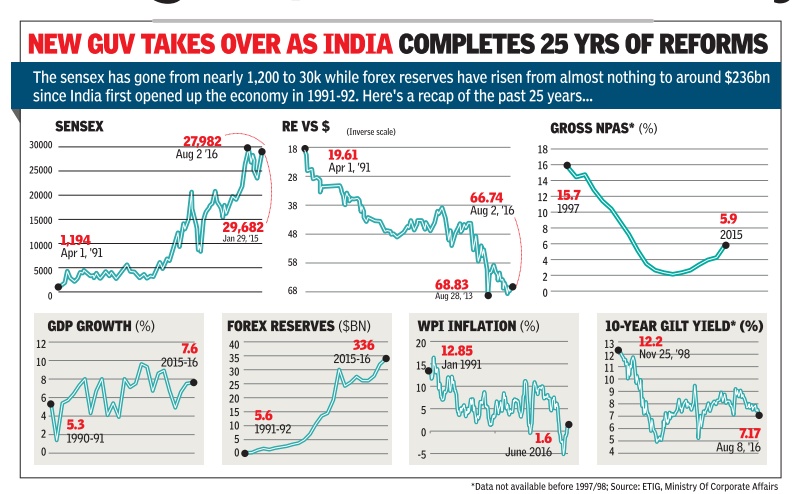

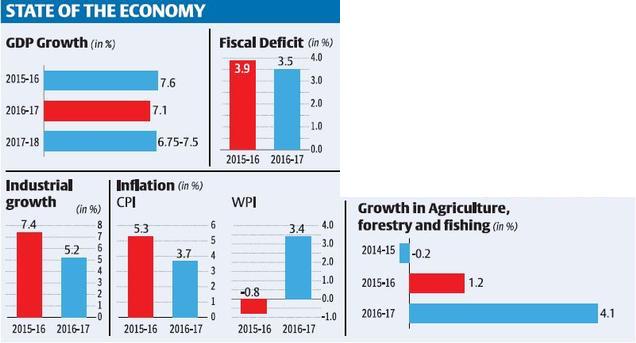

The country's economy grew 7.6% in 2015-16, the fastest in five years, while growth in the fourth quarter clocked 7.9%, keeping India ahead as the fastest growing major economy in the world.

The GDP data also brought cheers for the government, which has completed two years in office and is showcasing revival of the economy as a major achievement. India's 7.9% expansion in JanuaryMarch (fastest in six quarters) is higher than China's 6.7% expansion in the same quarter.In October-December quarter Indian economy grew 7.2%.Growth was powered by strong expansion in the manufacturing, which grew 9.3% in 2015-16 compared to 5.5% in 2014-15 and the farm sector, which clocked a growth of 1.2% in 2015-16 compared to a contraction of 0.2% in the previous year. The growth in the farm sector was despite the impact of a drought. Policy makers lauded the improving health of public finances. “.. India continues to remain a bright spot in the world economy with robust macro-economic and fiscal parameters,“ the finance mini stry said in a statement. Economist said they expect a good monsoon to support improving growth in the months ahead.

“With renewed forecast of more than normal monsoon this year, the situation in agriculture is expected to improve significantly , which will eventually lead to revival of consumption demand, especially in rural areas,“ said Madan Sabnavis, chief economist at Care Ratings.

“This in turn should also boost investment sentiment and keep food inflation under control. Also implementation of various government schemes and 7th Pay Commission will have an important bearing. With continued strong performance of the service sector, GDP growth in FY17 should see strong contributions from each sector of the economy . We expect GDP growth in FY17 to be around 7.8%,“ he said.

But the numbers also showed some weak spots such as sluggish investment growth.

“Private consumption has emerged as the bulwark of economy in 2015-16, whereas investment growth has slowed.With excess capacity and high leverage, private consumption demand will have to rise further to pare excess capacity and encourage private investment. With normal monsoon, a mild kick to public sector wages and improved transmission of interest rates, private consumption demand is set to get a boost in 2016-17,“ said D K Joshi, chief economist at Crisil.

2014-16: Economic indicators

See graphic

Facts about Indian economy: 2015-16

[The Economic Survey: 2016-17]

Indians on The Move

New estimates based on railway passenger traf c data reveal annual work-related migration of about 9 million people, almost double what the 2011 Census suggests.

Biases in Perception

China’s credit rating was upgraded from A+ to AA- in December 2010 while India’s has re- mained unchanged at BBB-. From 2009 to 2015, China’s credit-to-GDP soared from about 142 percent to 205 percent and its growth decelerated. The contrast with India’s indicators is striking.

New Evidence on Weak Targeting of Social Programs

Welfare spending in India suffers from misallocation: as the pair of charts show, the districts with the most poor (in red on the left) are the ones that suffer from the greatest shortfall of funds (in red on the right) in social programs. The districts accounting for the poorest 40% receive 29% of the total funding.

Political Democracy but Fiscal Democracy?

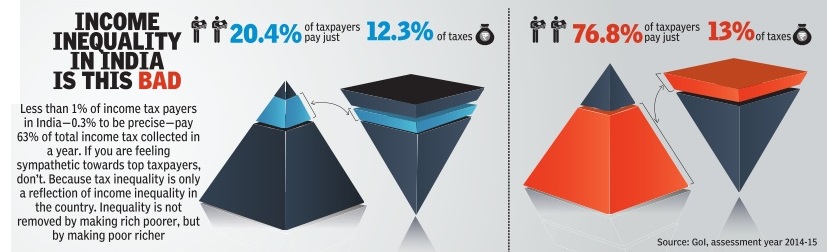

India has 7 taxpayers for every 100 voters ranking us 13th amongst 18 of our democratic G-20 peers.

India's Distinctive Demographic Dividend

India’s share of working age to non-working age population will peak later and at a lower level than that for other countries but last longer. The peak of the growth boost due to the demographic dividend is fast approaching, with peninsular states peaking soon and the hinterland states peaking much later.

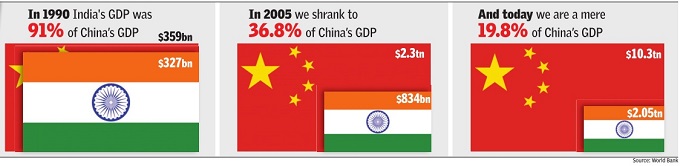

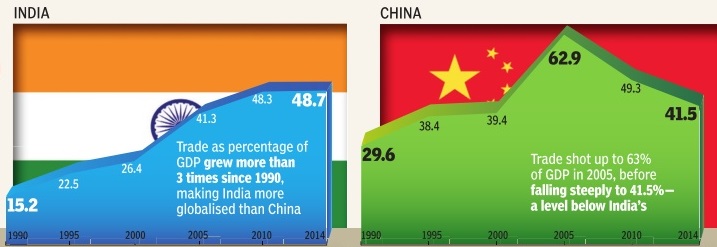

India Trades More Than China and a Lot Within Itself

As of 2011, India’s openness - measured as the ratio of trade in goods and services to GDP has far overtaken China’s, a country famed for using trade as an engine of growth. India’s internal trade to GDP is also comparable to that of other large countries and very different from the caricature of a barrier-riddled economy.

Divergence within India, Big Time

Spatial dispersion in income is still rising in India in the last decade (2004-14), unlike the rest of the world and even China. That is, despite more porous borders within India than between countries internationally, the forces of “convergence” have been elusive.

Property Tax Potential Unexploited

Evidence from satellite data indicates that Bengaluru and Jaipur collect only between 5% to 20% of their potential property taxes.

2015-16: economy grew 7.9%

Eco grew 7.9% in '15-16, faster than estimated 7.6%, Feb 01 2017: The Times of India

The Central Statistics Office (CSO) said the economy grew by 7.9% in 2015-16, a shade faster than previously estimated 7.6%, on account of better perfor mance by the farm and industrial sectors. CSO, however, left the figure for 2014-15 unchanged at 7.2%.

The revised growth rate would be the fastest pace of expansion for the economy in five years as data for the new series introduced in 2011-12 is available now. It would give the government ammunition to counter the Opposition's charge that the NDA's handling of the economy has slowed down the growth rate.

CSO had said that the economy was estimated to grow 7.1% during the current financial year but did not factor in the impact of demonetisation. The Economic Survey , released on Tuesday , however, indicated that the growth rate could slip to 6.5% due to the cash squeeze.

Higher growth rate would push up the base and could result in a further slowdown during the current finnacial year. It would, however, help the government show a better fiscal performance since the base has expanded.

Separate data showed the fiscal deficit up to December-end has touched 94% of the full year estimate of Rs 5.3 lakh crore.Fiscal deficit during April-December 2015 was estimated at 88% of the budget estimate.

The economy as in 2017

The Times of India, January 31, 2017

For the first time, along with a host of numbers and dry facts, the Economic Survey presented today also highlighted seven curious things about India, ranging from a perception bias against it to a fiscal disparity within it.

1. Indians on the move

New estimates based on railway passenger traffic data reveal annual work-related migration of about 9 million people, almost double what the 2011 Census suggests.

2. Biases in perception

China's credit rating was upgraded from A+ to AA- in December 2010 while India's has remained unchanged at BBB-. From 2009 to 2015, China's credit-to-GDP soared from about 142 percent to 205 percent and its growth decelerated. The contrast with India's indicators is striking.

3. New evidence on weak targeting of social programs

The Survey says that welfare spending in India suffers from misallocation. Districts with the most poor are the ones that suffer from the greatest shortfall of funds in social programs. The districts accounting for the poorest 40% receive 29% of the total funding.

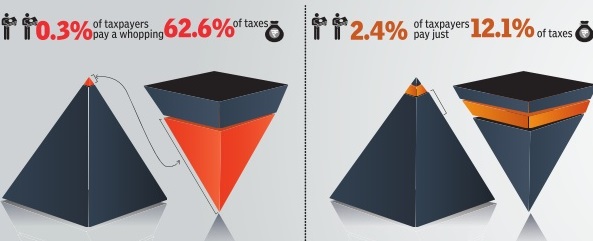

4. Narrow tax base

India has seven taxpayers for every 100 voters, ranking us 13th amongst 18 of our democratic G-20 peers.

5. India trades more than China

As of 2011, India's openness - measured as the ratio of trade in goods and services to GDP - has far overtaken China's. India's internal trade is also comparable to that of other large countries.

6. India's distinctive demographic dividend

There will a steady rise in India's working age population. While it will be slower compared to other countries, it is expected to last for much longer. Peninsular states are fast approaching the peak of the growth boost due to the demographic dividend.

7. Income divergence within India

During the last decade (2004-14), spatial dispersion in income has been on the rise in India, unlike the rest of the world and even China. Despite more porous borders within India than between countries internationally, the geographical graph of per capita income is skewed.

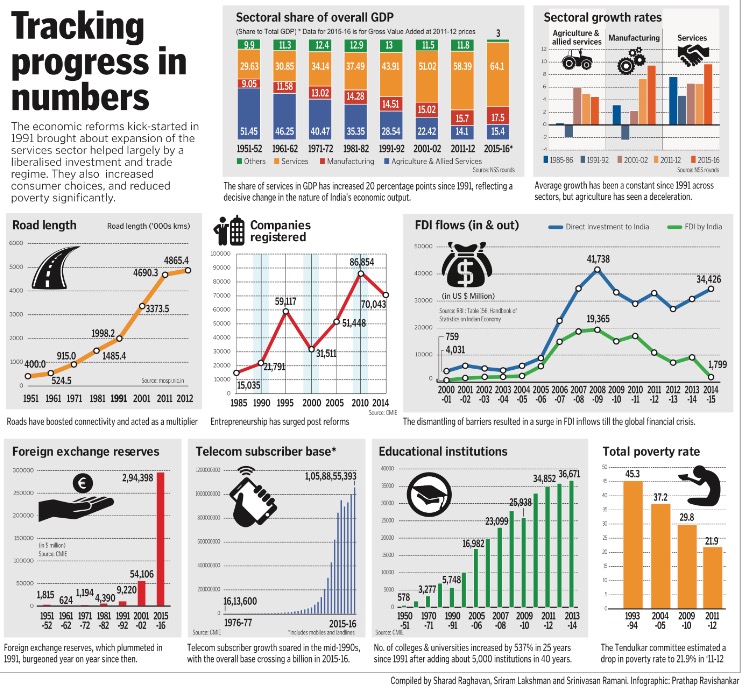

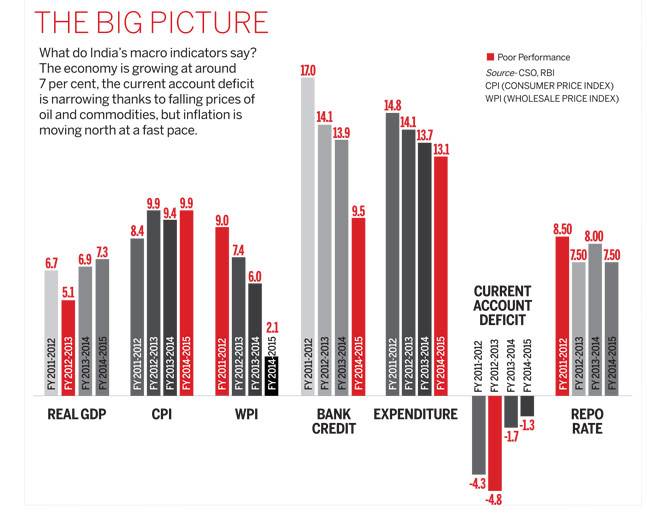

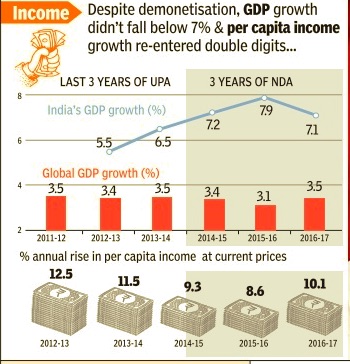

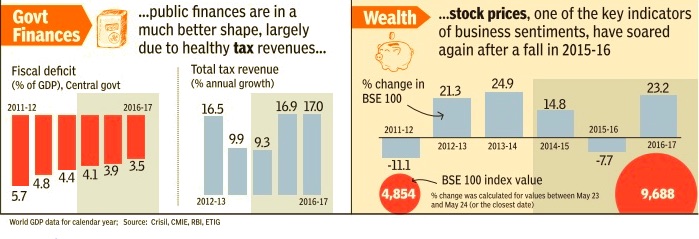

Economic indicators: 2012-14 vs. 2014-17

See graphics

Balance of payment/ current account deficit

2016-2017

Deficit widens due to lower remittances, March 24, 2017: The Times of India

Remittances from overseas Indians has been dropping continuously for the last five quarters, contributing to the widening of current account deficit (CAD). The trade gap has also widened due to lower software exports.

Balance of payment data released, shows that net personal transfers -which are largely remittances by Indians employed overseas--fell to $13.6 billion during the demonetisation quarter from $14.9 billion, a drop of 9.7%.

According to numbers released by the RBI, the current account deficit widened to $ 7.9 billion (or 1.4% of GDP) in Q3FY17 as compared to $ 7.1 billion (1.4% of GDP) in Q3FY16 and $ 3.4 billion in (0.6% of GDP) in Q2FY17. The CAD is the difference between income from exports and imports, plus the difference from between outbound and inbound investment income.

A statement issued by the Central bank said that the CAD widened despite a slightly lower trade deficit year-on-year, primarily on account of a decline in net invisibles receipts. Invisible includes remittances from software, services and money sent by Indians working oversea. Net services receipts moderated compared to Q3FY16, due to a fall in earnings from software, finan cial services and charges for intellectual property rights.

From April to December, however, the deficit halved to 0.7%, from 1.4% a year ago.

This was primarily because of fall in earnings from software, financial services and charges for intellectual property rights.

Earnings from software exports have been declining year-on-year, but the third quarter has seen a sequential increase in software exports over the second quarter.

The net foreign direct investment of $9.8 billion during the reporting quarter was marginally lower than last year. The RBI said that there was a net outflow of portfolio investment of about $11.3 billion during the period in both equity and debt segments, as against a net inflow of $0.6 billion in the year-ago period. During the current fiscal, net FDI rose 12.3% to $30.6 billion as compared to April-December 2016.

2016 : Demonetisation

M.G.Arun and Shweta Punj , Down and Ouch “India Today” 24/11/2016

See graphics:

Impact of demonetisation of high value currency (November 2016) on different sectors of the Indian economy- Agriculture, Micro and small units and Transport

Destinations for black money in India; share of cash in the money supply, India and the world

Split of the money in circulation by value in FY 2016

From: M.G.Arun and Shweta Punj , Down and Ouch “India Today” 24/11/2016

From: M.G.Arun and Shweta Punj , Down and Ouch “India Today” 24/11/2016

From: M.G.Arun and Shweta Punj , Down and Ouch “India Today” 24/11/2016

The usually bustling vegetable and fruit market under the Maharashtra Agriculture Produce Market Committee (APMC) at Vashi in Navi Mumbai wears a desolate look on Saturday, November 19. The 5,000-strong traders at the mandi laze near their wares on a sweltering afternoon, as just a few turn up to buy. Prices of vegetables and fruits have crashed by half in this wholesale market, one of the state's 305 regulated mandis, ever since high-value currencies were demonetised through a surprise government announcement on November 8. "Business has fallen from Rs 8-10 crore earlier to just Rs 4 crore at present, says Sanjay Pansare, a former director at the APMC. The number of trucks coming to the market has halved, with the transport of fruits from interior Maharashtra almost halted, while several loads of vegetables are left to rot. What's more scary, says Pansare, is that no one knows how long this will last.

The 'demon' in demonetisation is in the beginning, they say. As demonetisation entered its third week, scenes such as this have become all too common, the country struggling to come to terms with Prime Minister Narendra Modi's black money hunt, the biggest such since Independence. Various agencies have estimated black money (including but not only cash) at roughly 20 per cent of India's GDP, at over Rs 30 lakh crore (the World Bank said it was 23.7 per cent of the GDP in 2007; Mumbai-based Ambit Capital has put the figure at 20 per cent of India's $2.3 trillion, or Rs 156 lakh crore, economy). But the move, unprecedented as it was (the earlier such measure in 1978 by the Morarji Desai government also targeted high-value notes but they comprised a tiny fraction of the total currency in circulation), has also badly hit several sectors of the economy, and much of the so-called informal sector, which is variously estimated to account for 45-60 per cent of India's GDP. From agriculture to construction to automobiles, the sudden move to make Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 notes illegal has brought several legitimate businesses to their knees. That's not surprising as the demonetisation has suddenly sucked out 86 per cent of the Rs 16.24 lakh crore currency in circulation (as per Reserve Bank of India March 2016 estimates), affecting the livelihood of around 482 million who earn cash incomes, according to IndiaSpend, a non-profit data research firm. The government justifies the surprise move by stating that any forewarning would have rendered useless the very intent of the strike, giving black money hoarders enough time to launder the money. Modi has pledged that the short-term pain is worth it for the glorious long-term prospects-cheaper homes, less corruption in government offices, and lower interest rates for home buyers and industry. But many feel the economic backlash-even the most conservative estimates see a 0.5-1 percentage point slide in GDP growth for the next three months-may be just too much to handle. Ambit Capital predicts a slide in GDP growth from 6.4 per cent in the first half of this financial year to just 0.5 per cent (year on year) in the second half. It has also cut India's growth forecast for financial 2017-18 to 5.8 per cent from 7.3 per cent.

SHOCK THERAPY

The Opposition, as expected, came down heavily on the government for causing so much disruption and heartburn, with a dim chance of any credible outcome. Former finance minister P. Chidambaram said the economic impact of demonetisation will be felt in phases, beginning with a decline in trade in perishable goods and moving on to impact daily wagers in small industrial units, in places like Surat in Gujarat or Tirupur in Tamil Nadu, where layoffs and retrenchments have already begun. Industry body CII said demonetisation will adversely impact the third quarter earnings of corporate houses, particularly those in retail trade, unless the cash crunch is alleviated by end-November. Pronab Sen, the country's former chief statistician, cautioned that India's GDP growth rate could take a knock of 1 to 3 percentage points in the next two quarters. Credit Suisse analysts, led by Neelkanth Mishra, said it may take many years for the currency in the black market to replenish, hurting real estate/land transaction volumes, and hence prices. "The worst affected will be 80 per cent of construction jobs, 60 per cent of cement demand, and discretionary consumption," they said. With GST to be implemented from April 1, the economy is likely to be disrupted for 9-12 months, they added. Ratings firm Crisil estimates that the cash crunch will hit private consumption demand, which comprises 55 per cent of the GDP, thus lowering the GDP growth in the third and fourth quarters of the current fiscal. This will also lead to a build-up of unsold goods in the manufacturing sector, adding to its woes.

But the government is defiant. Modi has created a "new normal" of white transactions with his crackdown on black money, finance minister Arun Jaitley said in New Delhi on November 21. Demonetisation will lead to a jump in private investment and more public spending on welfare measures, he asserted. The country annually borrows Rs 4-5 lakh crore. After demonetisation, these funds (referring to the currency likely to be extinguished-estimated at Rs 3-4 lakh crore-could be transferred by the RBI to the government as dividend, though economists are split on the possibility of this happening) could be used for public spending-on creating new infrastructure, for example, or doles for the poor. The government has redrawn rules almost every day to soothe the pain of the cash crunch. On November 21, the RBI relaxed rules for classifying bad loans for small borrowers and provided 60 more days for the repayment of housing, car, farm and other loans worth up to Rs 1 crore. The relaxation applies to dues payable between November 1 and December 31. The central government has also constituted committees of additional secretaries, joint secretaries and directors for visiting states and Union territories to study and report on the status of implementation.

THE NATION QUEUES UP

In India, very rarely is politics dull and boring. But the past three weeks since Modi decided to swap most of India's currency have been epochal. After nearly 26 years since India welcomed its first bold set of reforms in 1991, Indians queued up to take out their money from the ATMs that have sprung up across the country. There are over 200,000 ATMs in India today, so much so that a generation of Indians does not know of a time when withdrawing money meant a trip to the bank. Since the demonetisation, there are restrictions on how much and how frequently cash can be withdrawn. Most importantly, less than a third-at last count, 60,000-ATMs are dispensing new cash. Finance ministry sources say all ATMs will be recalibrated by November 28 to withdraw new currency.

November will go down as a month of unprecedented change and upheaval in India. And grim reports - of sacks full of cash in trash cans, jewellery stores witnessing a mindboggling spike in sales in the hours between Modi's address and the midnight clampdown, deaths linked to the shock and pain that came with the measure, bankers wearing masks to beat the stench of stale money - have exposed India's vulnerabilities, inequities and inefficiencies to the world. While the long queues to withdraw and deposit money in urban areas were debated round the clock in the media, certain critical sectors that form the economy's backbone were being put through the wringer, unheeded.

THE AFTERMATH

Major shopping markets in the Delhi-National Capital Region (NCR), such as Sarojini Nagar, wore a barren look for days as customers kept away. At Chennai's Koyambedu market, known to be one of Asia's largest for perishable goods, sales dipped by half, with garbage trucks moving in and out to remove rotting fruits and vegetables. Adding to the problem was the sparse banking facilities in the rural areas. In 2015, while there were 7.8 branches for 100,000 people in rural India, the number was double-18.7 branches-in the urban areas. The government also disallowed cooperative banks across the country to accept deposits or exchange old currency notes after the first few days-ostensibly to prevent them from being misused by black money hoarders, virtually depriving those in far-flung villages of any source of cash. India's rural economy, on which 800 million people depend, is largely driven by cash. The unorganised or informal sector accounts for more than 90 per cent of the workforce in the country and contributes almost 50 per cent to the national income, the CII said in a 2012 report. In agriculture, which employs 49 per cent of the population, nearly 97 per cent of jobs are informal. The timing of the demonetisation, at the start of the rabi season (October to March), hit farmers hard, except in some states such as Punjab, where farming is more organised. The cash crunch might affect sowing. Many farmers may be forced to start sowing late as they are unable to purchase seeds, fertilisers and diesel (to run irrigation pumps) for the next crop cycle. Any delay in sowing can affect the yield. Farmers were expecting a bumper crop this year after two years of back-to-back drought, which saw agriculture contracting by 0.2 percentage points in 2014-15 and growing no more than 1.2 percentage points in 2015-16. With 2016 recording normal rainfall, agriculture was expected to grow at 4 per cent this financial year, according to Crisil. That is now unlikely, and the rabi sowing will be down by 30-40 per cent, estimates Sen. Though the government, on November 21, allowed farmers to buy seeds for the rabi crop with old notes, the decision may have come too late.

Several other businesses, such as cement, steel, construction and automobile, are in dire straits (see box: Pangs of the Purge). The construction sector, which employs 30 million, has two major components-large government infrastructure projects and realty. Realty projects, especially of smaller developers, will be in limbo in the short term. Government projects have greater resilience, but sub-contractors in such projects, too, are finding it hard to pay for labour, leading to project delays. Cement and steel, closely aligned to construction, have also been badly hit. The cement sector is likely to see 15-20 per cent drop in demand until December and a subdued 3 per cent growth in the fourth quarter of the financial year, Deutsche Bank Markets Research said in a report. The secondary steel sector will be impacted as most of the business conducted by mini mills and rolling factories is cash-based. The downstream stainless steel industry, which produces 30 million tonnes of steel and is concentrated in cities such as Jodhpur, Mumbai, Ahmedabad, Delhi and Chennai, has also been hit hard, says N.C. Mathur, president of the Indian Stainless Steel Association. Meanwhile, wary investors drove the benchmark Sensex to a six-month low of 26,228 on November 17, amid lingering worries over the economic impact of demonetisation even as foreign portfolio investors resorted to heavy selling in Indian stocks. On November 22, the rupee closed at a fresh nine-month low of 68.26 against the US dollar on high market volatility. Even taking the government's declared intention for the move at face value, the question that looms is whether the demonetisation could have been done differently. "This is simply an exchange of old notes for new and not demonetisation. The world has changed, in the sense that it is more difficult to do demonetisation," Chidambaram said in an interview. Terming the cashless economy as a "foolishly utopian" concept, he said all big economies have around 20 per cent cash component. "The US has an 18 per cent cash economy; it stands at 12.7 per cent for China," he said, adding that 22 per cent of the Indian economy is cash-based. Many economists root for a lowering of taxes and giving fewer exemptions as an alternative to demonetisation (see story: The Verdict). The fast rollout of GST and the Direct Taxes Code were seen as measures that would bring more individuals into the tax net through voluntary compliance, without loopholes for evasion.

Montek Singh Ahluwalia, former deputy chairman of the erstwhile Planning Commission, says it is more important to address the issue of black money generation than chase black money stacked up as cash. "People are disgusted with black money being generated through corruption," he said. Ahluwalia advocates transparency in government dealings, a rejig of the country's tax system and implementing land reforms as key measures for tackling black money generation in the long term.

While some businessmen spoken to were ready to endure the cash pain in the short term, others were worried that their businesses may be hit so hard that recouping the losses may take really long. Nikunj Sanghi, managing director of JS Fourwheel Motors Ltd and former president of the Federation of Automobile Dealers' Association, says the auto sector has been hit badly, with car sales slipping nearly 75 per cent since November 8. "Buying a car is not a priority any more, and news going around about government scrutiny of high-value purchases hasn't helped either," he says. The turbulence in the sector could last at least two quarters (six months), he feels, wiping out the car sale growth seen in the past one year. Demonetisation has thrown the goods transportation/trucking business across the country into complete disarray, a statement from the Delhi Transporters' Association said on November 22. As much as 80 per cent of the trucks have stopped plying, it said. Real estate will be much worse off. "In unorganised real estate, the impact can be severe because of a high amount of unaccounted - for money," says Arvind Mahajan, partner and head, infrastructure and government services, KPMG. According to Ficci, as much as 30 per cent of the transactions in the Rs 6.5 lakh crore real estate sector (2014 estimate) are carried out using unaccounted - for money.

Even if one is ready to go through the pain, what will be the tangible benefits in the medium and long term? Experts at the National Institute of Public Finance and Policy (NIPFP) worry that there aren't enough facts to prove that the cash that will be extinguished will be indeed black money. It is possible that these cash balances were used as a medium of exchange, as in informal sector transactions, or set aside to be used in emergencies (a housewife would stack up cash for domestic exigencies), the think-tank said in a paper on November 14. In that case, extinguishing it would lead to a contraction of the economy. Besides, as long as cash transactions continue, black money would keep coming back. "Unless you can move a large number of people to the digital economy, you will still generate black incomes," says Kavita Rao, lead author of the paper. The last few days have indeed seen an upswing in digital transactions across the country. Paytm, the largest Indian mobile payment wallet company with more than 100 million users and two million transactions a day, reportedly saw a three-fold jump in app downloads in the first two days following demonetisation. However, India cannot go cashless in a hurry, given that millions have no access to banks or are too poor to afford smartphones. India's unbanked population stands at 233 million, according to a PricewaterhouseCoopers report published last month. As many as 182 million new accounts were created in 2014 under the Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana to ensure a bank account for every Indian household, but it will take quite some time before they can fully start using modern banking services, such as ATMs or credit/debit cards. The country had 24.5 million credit cards and 661.8 million debit cards in operation as on March 2016, RBI estimates say.

Meanwhile, the jury is out on the impact of demonetisation on the banking sector, which has been working round the clock since Modi's announcement. The RBI said on November 21 that Rs 5.44 lakh crore worth of scrapped Rs 500/1,000 notes had been collected at various banks till November 18 following demonetisation. (Banks also disbursed Rs 1,03,316 crore over the counter and through ATMs between November 10 and 18.) But this need not necessarily lead to more liquidity in the system, since credit offtake has been already low, and demonetisation will further aggravate the problem. The bonanza banks will get with increased deposits does not mean their nearlyRs 6 lakh crore worth of non-performing assets or bad debt do not have to be dealt with. On November 22, ratings firm Fitch reaffirmed its 'negative' outlook for India's banking sector, saying the financial standing remained 'fragile' without bigger capital infusions and that the government's action on bank notes could end up having a mixed impact. Although demonetisation would lead to a surge in deposits, allowing banks to eventually lower lending rates, borrowers in sectors that rely on cash could struggle to service their loans, Fitch said. Moreover, the deposits could eventually be withdrawn as the dust around demonetisation settles.

THE ROAD AHEAD

So how is Modi's big gamble likely to pan out? If the government is able to stick to its timeline of 50 days to restore normalcy, growth will be back on track. If the government misses that deadline, the path will be perilous. Economists caution of a deflationary scenario, characterised by weak demand, low prices and low growth. The faster the government gets a handle on the money supply, the lower the collateral damage. In any case, a slowdown in growth is almost certain, at least for the next two quarters. Critics say the frequent relaxations being announced by the government, such as allowing withdrawal of Rs 2.5 lakh for weddings (albeit with caveats), are proof that the demonetisation drive hasn't been thought through. Also, many haven't taken kindly to the government's reluctance to share information on the impact of demonetisation or the path to recovery.

A lot hinges on implementation of key tasks, such as printing 50 billion notes (a three-to-four-month-long exercise, if the currency printing presses run at full capacity) and ensuring that money supply is restored. Former RBI deputy governor K.C. Chakrabarty says banks will take up to six months to replace the demonetised currency. "The entire country's machinery is geared towards this project; there is absolutely no fiscal gain. We'll have to lower the GDP target," says a Mumbai-based economist. However, there's an upside. Crisil says the adverse impact on consumption will be temporary and demand will rebound once interest rates and inflation fall after the demonetisation and the process of replacing the currency is completed.

With no precedent for such a massive policy drive, it becomes extremely difficult to imagine the outcome. But it must be said that while only shock therapy could have struck at the heart of India's black economy, its implementation could have been far more efficient.

See also

Economy: India 1

Economy: India 2 (Ministry data)

And also...

Income Tax India: Expert advice, 2016-17