Corporations, corporate performance: India

(→Sales revenue) |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[File: India and the world, Number of listed companies (July 2015).jpg|India and the world: Number of listed companies (July 2015); Graphic courtesy: [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Gallery.aspx?id=09_09_2015_010_011_002&type=P&artUrl=STATOISTICS-TOP-OF-THE-LIST-09092015010011&eid=31808 ''The Times of India'']|frame|500px]] | [[File: India and the world, Number of listed companies (July 2015).jpg|India and the world: Number of listed companies (July 2015); Graphic courtesy: [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Gallery.aspx?id=09_09_2015_010_011_002&type=P&artUrl=STATOISTICS-TOP-OF-THE-LIST-09092015010011&eid=31808 ''The Times of India'']|frame|500px]] | ||

| + | |||

{| Class="wikitable" | {| Class="wikitable" | ||

|- | |- | ||

Revision as of 22:57, 15 September 2018

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Brands, the most valued

2017

April 16, 2018: The Times of India

From: April 16, 2018: The Times of India

See graphic:

The most valued Indian brands of 2017

Despite the growth in the entertainment and telecom sector, five of the top 10 most valuable Indian brands remain banks and financial institutions. While the combined value of the country’s top 50 brands is estimated at $105 billion, over half of that value is held by the top 10 alone.

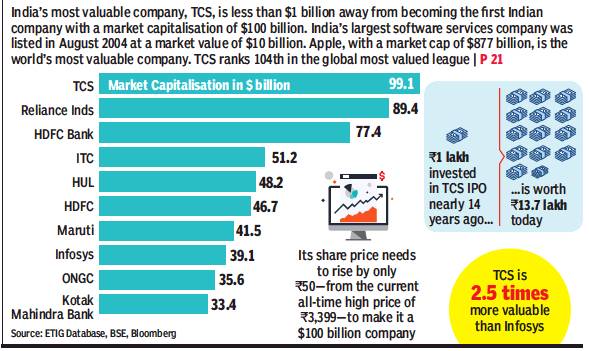

Market capitalisation

From: April 21, 2018: The Times of India

See graphic:

The Market capitalisation of India’s top ten companies, presumably in early 2018

Corporate debt

2016/ debt-to-GDP ratio is 55%

Corporate debt in emerging market economies including India, which used to average at 49% GDP nearly a decade ago, has now risen to 55% of the GDP , according to a latest RBI report.

India stands at the seventh place when measuring its government debt-to-GDP ratio -far behind countries such as China, Indonesia and Malaysia. The report also sheds light on how the system could be setting itself up for more cases of wilful defaulters like the now defunct Kingfisher Airlines. In a study of firms with more than $1-billion assets over 19 years, it was found that bigger corporates tend to be more leveraged post a crisis, compared to smaller firms.

Why it matters? In December, the RBI, in its fifth bimonthly policy statement, held rates for the first time in 2016, given the excess liquidity entering the system post-demonetisation. From some qu arters, the low-interest rate regime was hailed as the right time for pushing more loans to consumers, but the latest RBI report cautions against such a move. Titled, `Corporate Leverage in EMEs: Has the Global Financial Crisis Changed the Determinants?', the report draws parallels to the 2008 financial crisis.

“The post crisis period was characterised by abundant global liquidity and search for yield, which possibly resulted in lenient creditscore evaluations and leverage built-up. It is also possible that these firms with low profit took advantage of their possible future upturn and borrowed cheaply from debt markets,“ said the report.

Given the RBI's successive interest rates and current neutral stance, it is possible that we are on the cusp of a change in the policy rate cycle. And its at this juncture, the reports warns that lenders need to exercise more prudence.

Family firms

After the liberalisation of 1991

How the good old family firm fared

1991 was a turning point for the Indian economy. It was also a wake-up call for family-owned businesses. Not everyone made the Big Leap. Sunday Times finds out why

Prabhakar Sinha, Reeba Zachariah & Namrata Singh

Change, they say, is the only constant in life and businesses are no exception. India’s growth story shows that those who embraced change post-1991 have not only survived but excelled. Those who resisted simply fell behind.

Take Bajaj Auto, scooter manufacturer, and Hindustan Motors, who make the Ambassador car. Both are family-owned; both enjoyed near monopoly on the domestic market before globalization. Those were the days of queues and a five-year wait for a Bajaj scooter. But economic liberalization brought in global players like Honda, TVS and Suzuki. The competition forced Bajaj to change tack and venture into the fast-growing motorcycle segment. It finally abandoned scooter-production, once the sum and substance of its identity. Today, Bajaj is India’s second largest two-wheeler maker, after Hero Honda.

Not so Hindustan Motors of the C K Birla Group, which continued to flog its old car model and eventually lost the race to newer, racier entrants.

Girish Vanvari, executive director of global consultancy firm KPMG, says family ownership can give a company the unique opportunity to be quick to adopt change and it is this that counts in a competitive, globalized environment. Vanvari cites the Malvinder-Shivinder Singh Group as an example. The group was Ranbaxy’s original promoter but exited the family business. The Singhs sold their stakes in Ranbaxy to focus on healthcare, a manpower-dependent sector in which India is believed to have a natural advantage. The moral of the story? Decisions must be made on the basis of “available opportunities”, not emotional attachment, says Vanvari.

Azim Premji is another worthy example. He decided to shift focus to software development even as his flagship family firm, Wipro Ltd, busily produced vegetable oil and electric gadgets. His decision transformed Wipro into a world-class software company.

Richard Rekhy, advisory head of KPMG in India says business success requires long-term strategic focus rather than a short-term, operational, result-driven approach. Indian family-owned businesses are doing well in the globalized environment, he says because they generally have the flexibility to adopt alternative strategies relatively quickly. Family management also makes for commitment and continuity.

Interestingly, a 2007 Citigroup report pointed out that investors place a premium on firms in which family insiders wield significant, but not absolute, control. So why have some family firms failed? Consultants, who refuse to be quoted on this, say it’s a mix of short-term strategies and get-rich-quick schemes. Groups such as the Modis and the Usha group of Vinai Rai flourished before the advent of globalization. They formed a number of joint ventures with foreign partners, but hardly any of them survive.

Exceptions apart, globalization has generally helped India’s family-owned companies to flourish — particularly those where control systems are in place and day-to-day activities are allowed to be managed by professionals. One of the best examples of this is the Bharti group. At Bharti Airtel, the management, which is controlled by promoter Sunil Mittal, encourages independent directors to meet separately outside board meetings. The company also appoints a lead independent director who represents and acts as spokesperson for independent directors as a group. These processes ensure transparency and greater involvement of independent directors in the company’s decision-making process. It also ensures that independent directors act in a coordinated manner to challenge management decisions that are not in line with longterm shareholder interests. Today, Bharti Airtel is one of Asia’s largest telecommunication companies.

Sales revenue

2015-16: worst year since 1991

Atul Thakur, February 12, 2018: The Times of India

profit after tax,

of 21,000 Indian companies

From: Atul Thakur, February 12, 2018: The Times of India

HIGHLIGHTS

Sales during 2015-16 grew at a mere 1.6 per cent, worst since the liberalisation of economy in 1991

Over these 26 years, there have been five years in which growth in sales revenue crossed 20 per cent, with the 27 per cent recorded in 1994-95 being the highest

The year 2015-16 was the worst corporate India has seen in the post-liberalisation era in terms of growth in sales revenue. Sales during that year grew at a mere 1.6 per cent, shows data from the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE), an independent agency that tracks economic and business data.

The data, which collates information for over 21,000 companies, shows that other indicators like profitability and growth in employee compensation during 2015-16 were also among the worst in the last 26 years.

The data for the period 1990-91 to 2015-16 shows that there were only six years in which the combined sales of all the companies being tracked grew at single-digit rates and 2015-16 was by far the worst. The growth in corporate sales was just over 3 per cent for 2001-02, the second-lowest in this period.

Over these 26 years, there have been five years in which growth in sales revenue crossed 20 per cent, with the 27 per cent recorded in 1994-95 being the highest.

Not surprisingly, profitability took a severe beating. In 2015-16, profit after taxes (PAT) for 21,588 companies for which CMIE compiled data fell by more than 19 per cent, the third-largest year-on-year decline since 1990-91. The worst was in 2011-12 when profits had shrunk by over 20 per cent. In 2008-09, the year of the global financial crisis, posttax profits had gone down by nearly 20 per cent.

What makes the profitability picture even gloomier is that it comes on the heels of really low growth rates in post-tax profit in the previous two years —nearly 4 per cent in 2013-14 and 1.5 per cent in 2014-15. As a result, if one looks at the five-year period from 2011-12 to 2015-16, what emerges is that profits in the last of those years was about 25 per cent lower than in 2010-11.

This five-year period stands out as an exception in the entire post-liberalisation era. The years immediately following liberalisation saw extraordinary jumps in corporate profits. In 1993-94 and 1994-95, PAT increased by more than 90 per cent, the highest for this period. Similarly, 2002-03 and 2003-04 saw almost 58 per cent and over 69 per cent increases, respectively, in profits.

Given stagnant sales and declining profits, it should come as no surprise that 2015-16 saw one of the lowest increases in total compensation to employees — just above 9 per cent, the lowest since 2010-11. To put that in perspective, even 2009-10, the year following the global financial crisis that witnessed job losses and salary rollbacks, saw a more than 7 per cent increase in employee's compensation. Stagnant sales and falling profits also explain a continued fall in private investment growth, which started in 2012-13.

The CMIE data, mercifully, suggests that there was some respite from this gloomy situation for India Inc with a smaller sample for 2016-17, which covered 7,152 companies, showing an improvement in all these indicators. Sales were up just over 6 per cent, PAT 18 per cent and employee compensation nearly 10 per cent. Whether this trend will hold when data for the full sample of over 21,000 companies becomes available remains to be seen.

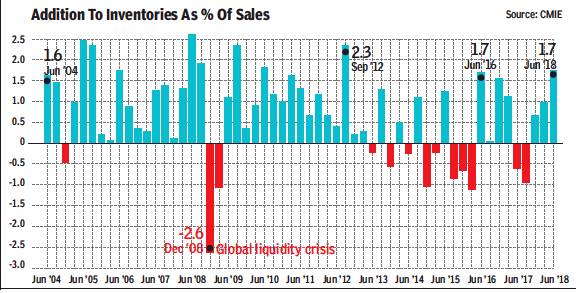

Sales vis-à-vis inventories

2004-2018

August 22, 2018: The Times of India

From: August 22, 2018: The Times of India

See graphic:

Addition to inventories as % of sales, 2004-2018, June

For quarter ending June, inventories as percentage of sales for listed non-finance companies climbed up to a 23-quarter high. The highest build-up was with makers of commercial vehicles, readymade garments and machinery. Is this a sign of demand slowdown towards the end of the last quarter or expectations of a high demand in the forthcoming busy season (Oct-Dec)? Experts are betting on the latter

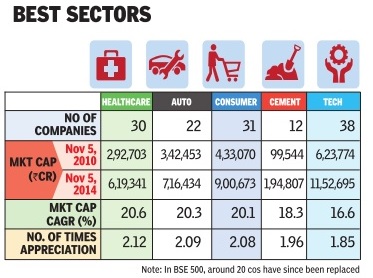

Sector-wise performance

2010-14

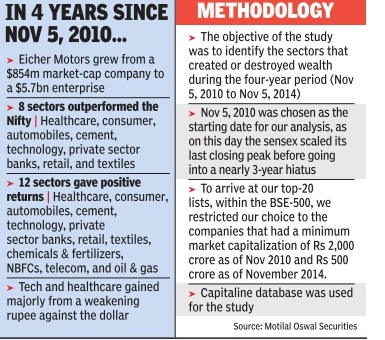

HIGH-GROWTH RIDE - Auto, Pharma top wealth creators in 4 years

The Times of India, Jan 01 2015

Partha Sinha & Shubham Mukherjee

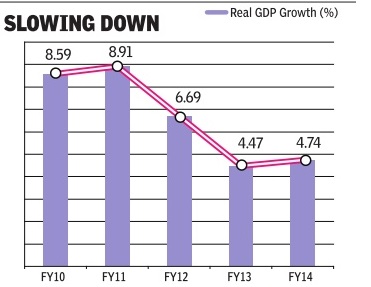

Realty, infra cos saw biggest value erosion since the 2010 highs as the economy went through a turmoil and the markets stagnated before rebounding to new peaks in 2014

Just over four years ago, the Indian economy was cruising at a near 9% annual rate of growth and on Di wali day in 2010, the sensex scaled a new high, closing above the 21,000 mark for the first time ever.However, since then as inflation rates spiked and interest rates spiralled, the government entered a phase of prolonged policy paralysis with the growth nearly halving to about 4.5% within two years. Rupee depreciation and widening current account deficit added to the negativity and it has since been a phase of almost flat GDP growth with muted corporate performance.

But a focused group of companies braved the headwinds and posted handsome returns for anyone who had invested in them, reveals a TOI-commissioned study done by Motilal Oswal Securities (See `Top Of The Charts' table). Significantly, most of these companies are not even leaders in the respective industries they operate in.Incidentally , the sectors that created wealth such as healthcare, consumer, automobiles, private sector banks and retail are all consumer-facing.

Topping the list of these outliers is Eicher Motors, makers of Royal Enfield bikes, with an eye-popping stock rise of about nine times in just four years. The stock rose from Rs 1,410 in early November 2010 to Rs 12,849 on this Diwali day . On the flip side, the biggest loser is MMTC with a current market capitalization of just about 5% of the value four years ago. So if you had invested Rs 100 in MMTC four years ago, you would be left with just Rs 5.

When contacted by TOI, Siddhartha Lal, MD & CEO, Eicher Motors, credited his performance to a differentiated product offering, providing a seamless chain between production to retail and an unrelenting focus on the two product lines motorcycles and commercial vehicles. “We are committed to the investor community and our longterm focus may have added to this (performance),“ he said.

Six of the top-20 wealth creators Eicher Motors, Motherson Sumi, TVS Motor, MRF , Wabco India and Apollo Tyres belong to automobiles. Consumer (Berger Paints, Bata India and Britannia), healthcare (Aurobindo Pharma, Sun Pharma and Torrent Pharma), and technology (Mindtree, HCL Technologies and Tech Mahindra) have contributed three companies each to the top-20 wealth creators' list. Besides, there are two NBFCs (Sundaram Finance and Bajaj Finance), a cement company (Shree Cement), a capital goods company (Havells India), and a Logistics company (Blue Dart Express).

Rajat Rajgarhia, MD, institutional equities, Motilal Oswal Securities, puts the findings of the study in perspective. “ Any time is the right time to buy stocks; the art lies in stock-picking. Even during the last four years, when the market indices have gone nowhere, numerous stocks have multiplied several times. On the flip side, hordes of stocks are now available at small fractions of their value four years ago,“ he said.

In contrast to the stocks that have grown investors' wealth multiple times, some of the worst performers have lost up to 95% of their value during this period, while a large number have witnessed around 75% value erosion (See `Bottom Of The Pile' table). All the stocks in the list of top-20 wealth destroyers have erased at wealth destroyers have erased at least 75% of their market capitali zation during the four-year period.

Some of the top laggards are from sectors which have been in a secular downturn for the past few years like power, real estate, infra structure and sugar. Companies like Shree Renuka Sugars, Bajaj Hindustan, JP Power Ventures, etc belong to this group.Metal companies like MMTC, Monnet Ispat and Hindustan Copper are in a cyclical downturn. There's a third group, consisting of companies which got into major controversies and faced regulatory scrutiny . DB Realty , Financial Technologies and Bhusan Steel belong to the third group.

Eight sectors outperformed the CNX Nifty over the four-year period: healthcare, consumer, automobiles, cement, technology , private sector banks, retail, and textiles (see `Best Sectors' table). All other sectors chemicals & fertilizers, NBFCs, telecom, oil & gas, capital goods, media, public sector banks, utilities, metals, real estate, and miscellaneous underperformed. A total of 12 sectors healthcare, consumer, automobiles, cement, technology , private sector banks, retail, textiles, chemicals & fertilizers, NBFCs, telecom, and oil & gas delivered positive returns. Seven sectors capital goods, media, public sector banks, utilities, metals, real estate, and miscellaneous delivered negative returns. The performance of the technology and healthcare sectors has been favourably impacted by a weakening rupee. Most of the sectors that destroyed wealth including real estate, metals, utilities, infrastructure, public sector banks, and capital goods are deeply cyclical and were affected by policy paralysis during the UPA-2 regime.