Economic history: India

(→2010-19) |

(→2010-19) |

||

| Line 63: | Line 63: | ||

| + | =1962- the prsent= | ||

| + | See [[Economy: India 1]] | ||

=2010-19= | =2010-19= | ||

== [[Start-ups: India ]] == | == [[Start-ups: India ]] == | ||

| Line 79: | Line 81: | ||

ECONOMIC HISTORY: INDIA]] | ECONOMIC HISTORY: INDIA]] | ||

[[Category:India|E ECONOMIC HISTORY: INDIA | [[Category:India|E ECONOMIC HISTORY: INDIA | ||

| + | ECONOMIC HISTORY: INDIA]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:Economy-Industry-Resources|H ECONOMIC HISTORY: INDIA | ||

| + | ECONOMIC HISTORY: INDIA]] | ||

| + | [[Category:History|E ECONOMIC HISTORY: INDIA | ||

| + | ECONOMIC HISTORY: INDIA]] | ||

| + | [[Category:India|E ECONOMIC HISTORY: INDIA | ||

| + | ECONOMIC HISTORY: INDIA]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Pages with broken file links|ECONOMIC HISTORY: INDIA | ||

ECONOMIC HISTORY: INDIA]] | ECONOMIC HISTORY: INDIA]] | ||

Revision as of 17:13, 4 September 2023

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Additional information may please be sent as messages to the Facebook community, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be gratefully acknowledged in your name.

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

A.D. 1 to 2003

SWAMINOMICS

The pioneering work of Swiss economic historian Paul Bairoch showed that in the ancient past, India had the highest share of world GDP, which was reduced to a humiliating fraction by the time India gained independence. The OECD asked eminent historian Angus Maddison to research the matter further.

In his magnum opus, ‘Contours of the World Economy 1–2030 AD: Essays in Macro Economic History’, Maddison estimated that in

1 AD, during the Hindu period, India accounted for 32% of world GDP, the highest share of any region.

During the Muslim period, India’s share gradually declined from 28.1% in 1000 AD to 24.4% in 1700.

It crashed in the subsequent period of British rule to just 4.2% by 1950.

India represented 33.2% of the world’s population in the year 1 AD. This was slightly more than its GDP share of 32%. So, Indian GDP was slightly below the world average. Italy was almost twice as rich under the Roman empire. India’s high GDP share reflected not prosperity, but high population.

Maddison estimates that India’s GDP stagnated at $33.75 billion from 1AD to 1000 AD, the Hindu-ruled period. Per capita income also stagnated at $450 as the population remained steady at around 75 million.

Why did the population not increase for a thousand years? Because drought, disease, and wars meant that merely staying alive was a challenge. Conditions were as bad in the rest of the world. In sum, the period from 1 to 1000 AD was one of poverty, economic stagnation, and high mortality.

Under Muslim rule, roughly between 1000 and 1700, India’s annual GDP almost tripled to $90.7 billion. Mortality fell substantially, enabling the population to soar from 75 million to 165 million. Population growth substantially offset GDP growth, so per capita income grew by barely a quarter, from $450 to $550. Still, there was an improvement, and a longer-lived one.

These trends intensified in the British period. Between 1700 and 1950, India’s GDP rose to $222.22 billion and its population to 359 million. However per capita income rose only marginally to $619.

British colonial claims of having uplifted a backward India were vastly exaggerated. However, India did not get poorer in per capita income terms in the British era. India’s share of world GDP plummeted mainly because incomes in the West soared after the industrial revolution.

Economic growth finally took off in India after it became independent.

After almost 2,000 years of negligible growth, per capita income soared to $2,140 by 2003. Mortality fell sharply, so the population rose to 1.05 billion by 2003 despite the spread of contraception.

The British Era

SWAMINATHAN S ANKLESARIA AIYAR, August 13, 2023: The Times of India

In his bestseller ‘An Era of Darkness: The British Empire in India’, which is a devastating demolition of the British Raj, Shashi Tharoor also cites Maddison extensively.

His long thesis cannot be discussed fully in a short column, but we can discuss his citations of Maddison. Maddison’s magnum opus ‘Contours of the World Economy, 1-2030 AD’ has figures slightly different from Tharoor’s. Maddison says India’s share of world GDP was 24. 4% in 1700 before British rule but fell to 4. 2% by 1950. Tharoor says, “The reason was simple. India was governed for the benefit of Britain. Britain’s rise for 200 years was financed by its depredations in India. ” Do Maddison’s actual figures support this? Between 1700 and 1950, Indian GDP went up from $90 billion to $222 billion, the fastest growth ever. India’s share of world GDP fell not because it was impoverished but because the Industrial Revolution helped other countries grow much faster. Improvements in health, and a British-enforced peace between princely states that had historically constantly warred, helped population soar from 165 million to 359 million. By contrast, the population grew not at all in the Hindu period, a grim reminder of how difficult things were in pre-British days. Was colonial rule the reason for India’s relatively low income and Britain’s high one? Maddison’s data does not support this claim. Even in the pre-colonial period 1000-1500 AD, Britain’s annual per capita income growth was thrice India’s 0. 04%. In 1500-1820, which was mostly pre-British, India’s per capita growth was minus 0. 01% against Britain’s 0. 27%. In 1820-70, the heyday of East India Company loot, India’s growth was 0% against Britain’s 1. 26%. In 1870-1913 under British rule, India had its fastest growth ever of 0. 54% per year. But that fell to minus 0. 24% in the final British phase 1913-50, when India was hit by the Great Depression and sharp decline in per capita food availability.

Britain’s own annual per capita income growth declined below 1% in 1870-50, not a sign of huge colonial benefit. When it lost its colonies in 1950-73, Britain’s per capita income growth rose to a record 2. 4%. This contradicts the thesis that Britain grew fast because of colonial exploitation. Its growth was due mainly to higher productivity. Colonialism helped but was not key.

On financial flows from India to Britain, Tharoor cites Maddison. “There can be no doubt there was a substantial outflow for 190 years. If these funds had been invested in India, they could have made a significant difference. ” This is surely true. Yet Indian history shows that tax revenues were typically not invested but wasted in luxurious aristocratic living and non-stop wars that left many rulers unable to pay their soldiers on time, encouraging loot. Hence, GDP grew slowly.

The East India Company looted the Indian aristocracy. But this hardly affected the Indian masses, who paid much the same taxes. The princely states, ruling 40% of British India, did not hand over their revenue to the Raj, yet their economic growth was very weak overall (with exceptions like Travancore). This suggests, alas, that keeping tax revenue in India did not benefit the masses or economic growth. The Nizam of Hyderabad was reputed to be the richest man in the world, but the areas he ruled remained among the poorest in India. Nationalist historians think India would have had a faster industrial revolution without the British Raj. The performance of the princely states — notably the biggest, Hyderabad — suggests otherwise.

Tharoor says British taxation was very onerous. Maddison, however, says that taxation of peasants was around 15% of GDP in Mughal times but plummeted to 3% by the end of British rule. The East India Company expropriated the Mughal aristocracy. But after direct rule from London, taxes were fixed in nominal terms which were eroded away by inflation. This not only slashed real taxation of the peasantry but greatly reduced their real debts too. British colonialism ceased to be profitable, one reason why it ended so smoothly.

This column does not assess the totality of British rule or Tharoor’s book, which has brilliant passages. But it shows that Tharoor has cherry-picked citations from Maddison to bolster his thesis. Maddison’s full picture is less critical of the Raj, highlighting its eight-fold increase in irrigation. The debate goes on.

1962- the prsent

See Economy: India 1

2010-19

Start-ups: India

See also, Start-ups: India

From: Dec 31, 2019: The Times of India

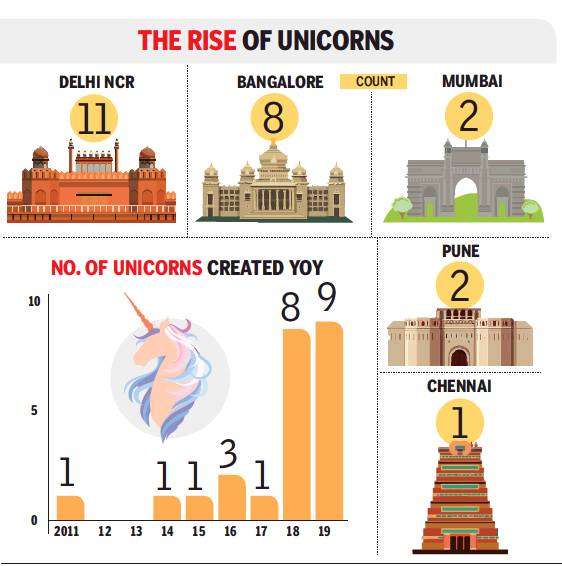

See graphic:

Number of unicorns created, 2011-19

2019

Dec 31, 2019: The Times of India

From: Dec 31, 2019: The Times of India

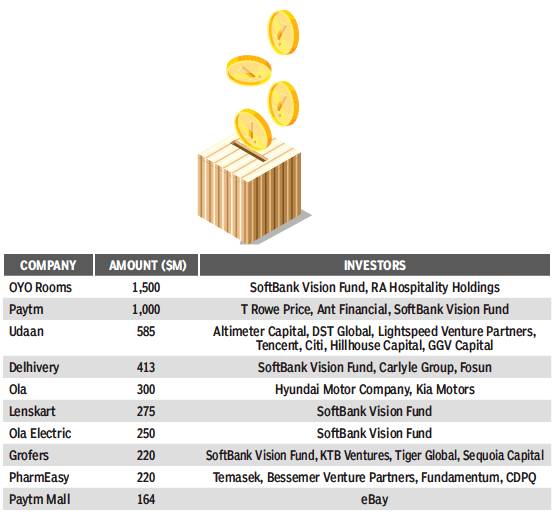

See graphic:

Companies, the invested amount and the investors, 2019

The Indian startup industry has come a long way. In 2010, startups raised just $550 million in venture funding, according to data from Tracxn.

At the time, top venture capital firms, like Sequoia Capital India and SAIF Partners, built portfolios in public markets and nontechnology investments, as India’s digital economy lacked depth. Online retail was just about starting out as Flipkart, Myntra and Snapdeal raised their first rounds of venture funding.

Since then, startups have changed the way consumption happens in India, thanks to the proliferation of smartphones and cheap data. The funding landscape in 2019 looked like this: 1,096 startups and venture capital-backed firms raised $14.4 billion — a 25-time increase in capital flow from 2010. Global investors, from Japan to Silicon Valley, have been pouring capital into firms, hoping these companies will leapfrog traditional business models in retail, payments, digital and other segments.

Already, some have established a strong mainstream presence, and this is evident from their association with India’s favourite sport: Paytm has been the title sponsor of the Indian cricket team since 2015 and edtech unicorn Byju’s replaced Chinese smartphone maker Oppo as the team sponsor earlier this year. Paytm founder Vijay Shekhar Sharma and venture investor Avnish Bajaj of Matrix Partners India reflect on the past decade and share their wish list for the coming one.

VIJAY SHEKHAR SHARMA, FOUNDER & CEO, PAYTM

Biggest game changer of the decade

“Billion-dollar funding rounds. At the start of 2010, raising Rs 100 crore, or $25 million, was considered a large round. Today, companies raise $1-billion round in India,” he said. In 2010, he was preparing to take his company, which focused on mobile value-added services at the time, for an IPO at a valuation of less than $100 million.

The plan was dropped, and Sharma steered the transformation to digital payments. Paytm is now worth $16 billion.

“The most formative event of the last decade was Flipkart raising $1 billion in July 2014, and we, at Paytm, have done it twice since then. These mega capital raises have been a culmination of investor appetite, talent in the country and size of the market. This is one thing I didn’t expect would happen in India,” he said.

Game changer for the next decade

“Valuation was the buzzword in this past decade. But in the coming one, startups should be known by how many billions in profits they generate. Entrepreneurs face a lot of opposition and scepticism; our methods are considered unconventional. I hope startups and digital businesses create billions in profits and give critics a fitting answer,” he said.

AVNISH BAJAJ, MD, MATRIX PARTNERS INDIA

Biggest game changer of the decade

More startups are toiling to stay in the game for the long haul instead of searching for quick exits. “The biggest positive surprise was the choice made by a number of founders to build to last. M&A activity was much lower than expected, apart from the Flipkart exit,” said Bajaj, who co-founded Baazee that was acquired by eBay in 2004, one of the first M&A exits in the Indian internet economy.

The announcement by Oyo’s founder, Ritesh Agarwal, to buy back close to 13% stake from early investors for $1.3 billion by taking a loan is being seen as an unprecedented move globally. “A very gutsy step by Ritesh!” said Bajaj, whose company has backed businesses like Ola, Dailyhunt and Mswipe.

Game changer for the next decade

According to him, the next step for Indian startups is to become more sustainable and mature, and to go for IPOs. “I would like to see 15-20 listed Indian internet companies that perform well in the public markets,” he said.

The top trends

Dec 31, 2019: The Times of India

1 CO-FOUNDER TAG AN HR TOOL

From unicorns like Zomato to mid-stage companies such as online pharma delivery player Medlife and meat delivery startup Licious, firms are giving the title of co-founder to new and existing executives. Gaurav Gupta and Ananth Narayanan joined Zomato and Medlife, respectively, years after the companies were launched, but they are still called co-founders. The strategy underscores the importance of executives and operators in the startup ecosystem. The trend is not entirely new. In 2006, Makemytrip’s Deep Kalra accorded the status to Rajesh Magow, the India CEO. But today, this approach has gained more significance. The Indian internet market is getting more competitive and firms need operators who are also recognised as co-founders by employees.

2 INDIA SEES ‘TECHLASH’

Big tech companies such as Facebook and Google faced greater scrutiny from regulators, lawmakers and employees in the US in 2019. India, too, witnessed a version of the pushback against large digital companies. This included changes in online retail laws, protests against food delivery players and the data privacy bill. Data localisation has become a major sticking point between the industry and the Indian government. A key fight on this front has been the entry of Facebook-owned WhatsApp into the payments business. The payments service has been stuck in beta since early 2018 because of a variety of reasons, including access to encryption and concerns over fake news on Facebook’s platform.

3 VALUATION HYPE: FIRST DEATH OF AN INDIAN UNICORN

A billion-dollar valuation does not necessarily mean success. Shopclues, which was valued at $1.1 billion in 2016, was sold at a valuation of less than $100 million to Singapore-based e-tailer Qoo10 in November. Shopclues had raised over $257 million in funding from the likes of Singapore’s GIC, Tiger Global, Helion Venture Partners and Nexus Venture Partners. But it struggled with several issues, including a fight among its founders and competition from Flipkart, Snapdeal, Amazon and Paytm Mall.

Several startups in the Indian market — Jabong and Freecharge, for instance — have been sold for far less than their original or perceived valuations. But Shopclues was the first that claimed to be a unicorn.

4 OYO’S BUSY, BUSY YEAR

For SoftBank-backed Oyo Hotels & Homes, 2019 was a year of ups and downs as it hyper-charged its aggressive expansion across the world. The most audacious move was the over $2-billion loan that founder Ritesh Agarwal, 26, took to triple his shareholding to 30% and infuse fresh capital into the business. The secondary transaction has been done at a valuation of $10 billion, double of Oyo’s valuation last year. The company has expanded to Europe with $415 million buyout of @Leisure Group and is opening 200 properties in the US. It has bought Hooters Hotel & Casino in Las Vegas.

The second half of the year was tough for Oyo. It is facing a revolt by hotel owners in India and China.

Recently, Oyo said it had laid off up to 500 employees.

5 SAY KIRANA FOR FUNDING

There are roughly 12 million kiranas in India. More and more startups are building business models to cater to this section. The services they offer include digitising ledgers and improving the supply chain. Kirana-focused startups raised over $260 million in funding in 2019, according to data compiled by Avendus Capital for TOI as against $70 million in 2018. Digital bookkeeping players OkCredit and Khatabook and logistics tech firm Elasticrun are among them. Udaan, which operates in a broader space, saw some of the largest funding rounds.

6 MOBILITY, E-TAIL 2.0

2019 was the breakout year for a new generation of startups in urban mobility and online retail space, as they attracted big funding and witnessed high growth. These firms are seeing faster growth than traditional players, though on a smaller base. It remains to be seen if they become a threat. In mobility, Sequoia- and Accel-backed Bounce is taking on Matrix- and Ola-backed Vogo in the scooter rental space. Bounce CEO Vivekananda HR tweeted in October that the platform had crossed 1 lakh rides a day in Bengaluru, about 13 months after launching a dockless option. Bike taxi player Rapido now records 5 million rides a month, up from 2.2 million rides a month in May this year.

New players have also emerged in the area of social commerce. Bulbul, Simsim, Dealshare and Wmall are leveraging video and social media to sell goods, raising their first major rounds of funding. Social commerce platform Meesho, which uses a network of resellers, raised $125 million from Facebook and Naspers this year.

7 SERIAL ENTREPRENEURS ATTRACT BIG BUCKS

In 2019, serial entrepreneurs and executives, who had previously worked with high-growth startups, were able to raise capital with some ease, at times without a business plan. They include CitrusPay co-founder Jitendra Gupta, who is starting digital banking firm Jupiter; Amit Lakhotia, a former Paytm and Tokopedia executive, who is building a venture for car parking management; and Nipun Mehra, a former Pine Labs and Flipkart executive, who is launching a B2B commerce venture for Southeast Asia. What has also helped VCs build conviction about signing large cheques at the idea stage is the amount of follow-on capital startups like Cred, started by Freecharge co-founder Kunal Shah; Curefit, built by Myntra’s Mukesh Bansal; and Udaan, a venture by former Flipkart executives, have attracted. These founders launched companies which have unique localised business models.

8 PAYMENT, FOOD DELIVERY COS BLEED

A battle for market supremacy in online retail and cab hailing marked the Indian startup scene’s years from 2014 to 2017. But in the past two years, the fight in digital payments and online food delivery spaces has grabbed the spotlight. It’s an expensive battle, according to the latest set of numbers. SoftBank-backed Paytm, Walmart-owned Phonepe and Amazon Pay suffered a collective loss of over Rs 7,283 crore ($1 billion) in the financial year that ended in March 2019. A staggering increase of 167% from Rs 2,729 crore ($386 million) in the fiscal ending March 2018. If one includes Rs 1,028 crore Google Pay spent on cashback during FY19, the loss figure for the industry stands at Rs 8,311 crore.

The total reported losses also shot up in online food delivery: Swiggy saw them increase nearly six-fold to Rs 2,364 crore (FY19), while Zomato saw them jump by 24 times to Rs 2,058 crore from Rs 84 crore in FY18. Ola-owned Foodpanda reported 230% increase in losses at Rs 756 crore, while UberEats’ India business is dragging down its global margins.

Record capital, mega rounds

Dec 31, 2019 The Times of India

From: Dec 31, 2019 The Times of India

From: Dec 31, 2019 The Times of India

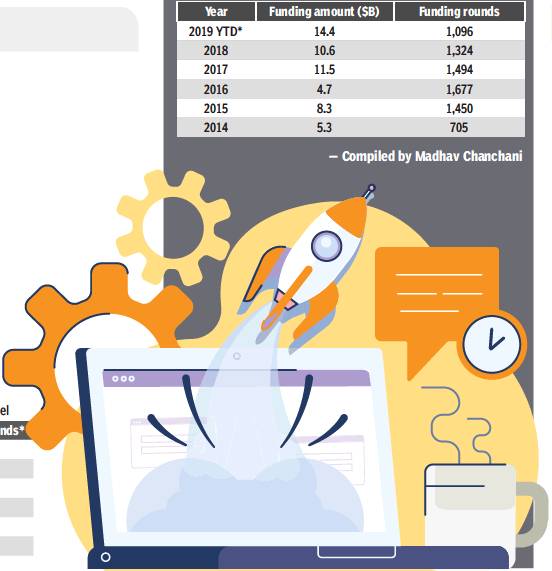

India’s startup industry was flush with funds in 2019 as capital flows peaked. TOI examines the developments and data that made the year an important milestone for the ecosystem

27 $100-MILLION ROUNDS

There were a record number of rounds of over $50 million — 62, up from 32 in 2018. The number of investments of over $100 million stood at 27 as against 17 in 2018 and just 10 in 2015. The boom in 2018-19 was different than the 2014-15 cycle because capital was concentrated in fewer companies. 2019 saw the return of hedge funds such as Steadview Capital, Tiger Global Management and Falcon Edge Capital. Plus, the arrival of a new set of investors at mid-stage — PE firms Goldman Sachs and General Atlantic and Chinese investors Tencent and GGV Capital, which have become increasingly active in the market.

“The good thing in 2019 was that there was decent amount of capital available at B and C stages, so most of our scaling and scaled companies managed to raise new rounds. Our advice to companies is to be prudent about how much cash you spend,” said Subrata Mitra, founding partner at Accel India.

Availability of capital has allowed startups to raise multiple rounds within 12 months. The result: their valuations have jumped.

For example, Home services marketplace UrbanClap’s valuation nearly doubled to $930 million in eight months and Meesho’s valuation almost tripled to $700 million in a similar period. Even software firms have seen their valuations grow.

But now, the number of these quick capital raises are taking longer and there are instances of investors pulling out of these rounds. “Fundamental questions come at the very end and confidence gets tested. There is a palpable nervousness and a much higher sense of paranoia in companies,” said a venture capital investor, who didn’t want to be named.

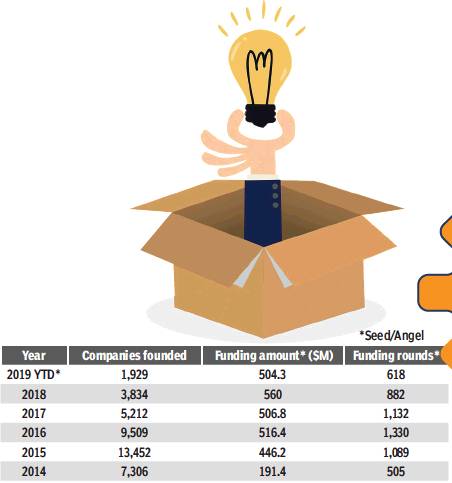

STARTUP FORMATION CONTINUES TO FALL

There were fewer new startups in 2019, nearly halving to 1,929 from 3,834 in 2018. The activity of starting up hit a high of 13,452 in 2015. Angel and seed funding, i.e. financing at idea stage, peaked the following year with 1,330 investments. Since then, angel funding and the number of new startups have fallen as many people realised that entrepreneurship or investing is not their cup of tea. The concerns over angel tax have also been a deterrent at early stage.

2019 began with an uptick in early-stage investment activity as the country’s largest venture capital firm, Sequoia, announced an accelerator-cum-seed-funding programme called Surge. This, in turn, prompted several VC firms, including Matrix Partners India and Silicon Valley accelerator Y Combinator, to step up their early stage activity. A record number of startups from India were picked for summer and winter batches. Accel, Blume Ventures and Venture Catalysts are the other active investors at early stage.

CHEQUE THAT – $14.4BN PUMPED INTO STARTUPS

2 019 was a record year for both startups and digital companies in terms of capital raised. The ecosystem received $14.4 billion of investment, a 35% increase compared to 2018, though the number of startups that attracted capital fell by 17%, according to data intelligence platform Tracxn. There were 1,096 deals in 2019. The previous record for capital was registered in 2017, when two mega investments by SoftBank — $2.5 billion in Flipkart and $1.4 billion in Paytm — lifted overall industry numbers.

Global investors remain confident about the Indian digital growth story. Consider the case of EtechAces Marketing and Consulting, which owns online financial services portals PolicyBazaar and Paisabazaar. In 2019, New York-based Tiger Global Management began talks to sell its 21% stake in EtechAces. It had first invested in 2014, when EtechAces was valued at less than $100 million. That valuation has now increased to over $1.5 billion. While Chinese internet conglomerate Tencent was already taking 10% stake, as EtechAces CEO Yashish Dahiya wanted them on board as investors, investment bank Avendus Capital was asked to get investors for remaining shares worth about $150 million. “Within three weeks we got over $1 billion of excess demand from who’s who of the financial investment world. If you can think of them, they were there,” Dahiya told TOI. Tiger Global eventually decided not sell the remaining 10% stake; the sale was called off. Dahiya declined to disclose the reason. Perhaps Tiger Global executives wondered why they were exiting a company which was drawing more global investors.

SOFTBANK STILL DOMINATES MAJOR ROUNDS

The Japanese technology and investment major remained in the headlines across the world, especially in Silicon Valley, for the wrong reasons. SoftBank’s biggest setback was coworking player WeWork’s botched public offering, which pushed its valuation down from $47 billion to $8 billion after a mega bailout package. The debacle also contributed to the ouster of WeWork founder Adam Neumann. The episode resulted in SoftBank cutting the expected size of its new Vision Fund to half of $108 billion it had planned earlier.

But despite the troubles, it continues to dominate mega rounds in India; it led or made follow-on investments in six of the top 10 deals. Its biggest deal was the $800-million infusion in hospitality startup Oyo. In new transactions, SoftBank backed eyewear retailer Lenskart, logistics startup Delhivery and electric vehicle infrastructure player Ola Electric.

Some major capital raises in 2019 were Paytm’s $1-billion deal with T Rowe and Ant Financial, which put its valuation at $16 billion, and business-to-business commerce major Udaan’s $585-million raise, which increased its valuation to $2.8 billion.

Tycoons faced bankruptcies, jail, death

Dec 31, 2019 The Times of India

NEW DELHI: For many Indian tycoons, 2019 turned woeful as lenders -- empowered by the nation’s recent bankruptcy law and desperate to clean up soured debt from their books -- started seizing assets of delinquent firms or dragged them into insolvency.

Indian banks wrote off a record $39 billion of loans in the 18 months through September in a bid to repair their balance sheets as they battled the world’s worst bad debt pile. Making matters worse, a shadow banking crisis led to a funding squeeze, crushing debt-laden businesses that were critically dependent on rollover financing.

“Life has come a full circle for tycoons that had enjoyed debt-fueled growth,” said Nirmal Gangwal, founder of distress and debt restructuring advisory firm Brescon & Allied Partners LLP. “Many firms collapsed like a house of cards. The downfall was rather unprecedented.”

The government has also been cracking down on economic crime to assuage public anger over absconding businessmen. It’s even barred some from traveling overseas if they were deemed a flight risk.

Here are some of the country’s biggest and most-storied businessmen who saw their fortunes fade. Spokespersons for these tycoons didn’t immediately reply to emails and text messages seeking comments.

Anil Ambani

The chairman of Reliance Group, which makes movies to metro lines, had a close shave with jail time in March before his elder brother and Asia’s richest man, Mukesh Ambani, bailed him out at the last minute. The woes of the ex-billionaire came to the fore when India’s top court asked him to pay Ericsson AB’s India unit about $77 million of past dues or go to jail since Anil Ambani, 60, had given a personal guarantee. His telecom carrier slipped into insolvency this year, while unprofitable Reliance Naval & Engineering Ltd. faced a cash crunch. Reliance Capital Ltd. is selling assets to pare debt. Ambani is also fending off Chinese lenders in a London court.

Malvinder & Shivinder Singh

Karma caught up with ex-billionaires and brothers Malvinder Singh, 47, and Shivinder Singh, 44, and how. Scions of a prominent business family, they once helmed India’s top drug maker and second-largest hospital chain.

In October, the two were arrested on charges of fraudulently diverting nearly $337 million from a lender they controlled. India’s market regulator found in 2018 that the brothers had defrauded their hospital company of about $56 million. The collapse of the $2 billion empire turned brother against brother, prompting their mother to broker a peace deal that was short-lived. In February, Malvinder accused Shivinder and their spiritual guru of fraud.

Shashikant & Ravikant Ruia

After a hard-fought battle to keep their flagship steel mill, the first-generation entrepreneurs finally saw the bankrupt Essar Steel India Ltd pass on to ArcelorMittal last month.

The $5.9 billion takeover was almost two years in the making with multiple legal wrangles. The group, controlled by Shashikant Ruia, 76, and Ravikant Ruia, 70, were also reprimanded by a UK judge in March this year for concealing documents. Started in 1969 as a construction firm, Essar Group diversified, investing about $18 billion between 2008 and 2012, and piled on debt. In 2017, the group had sold another prized asset, Essar Oil.

VG Siddhartha

Before jumping off a bridge into a river in July in an apparent suicide, the founder of India’s biggest coffee chain Cafe Coffee Day had penned a letter that spoke of pressure from lenders, a private equity firm and harassment by tax officials. He had spent much of the last two years pledging ever more of Coffee Day Enterprises Ltd. shares to refinance loans for ever shorter periods, at ever higher interest rates. “I would like to say I gave it my all,” VG Siddhartha, 60, wrote in the letter. “I fought for a long time but today I gave up.”

Naresh Goyal

The former ticketing agent who built India’s largest airline by value, stepped down as chairman of Jet Airways India Ltd in March, caving in to pressure from banks who took over the company. Cut-throat price wars and surging costs pushed Jet deeper into loss. The airline stopped flying in April and went into bankruptcy two months later as lenders failed to find a buyer. In July, an Indian court barred Naresh Goyal from flying overseas after the government said it was investigating an alleged $2.6 billion fraud involving Jet Airways.

Rana Kapoor

The founder of Yes Bank Ltd, which became India’s fourth-largest non-state lender, tweeted in September 2018 that his shares were invaluable and requested his children never to sell them upon inheritance. But trouble was brewing. The nation’s banking regulator, which found the lender had repeatedly under-reported its bad loans, refused to extend his tenure as chief executive officer. This forced Rana Kapoor, 62, to step down by end-January. Kapoor, who had pledged some of his Yes Bank shares in July, sold almost his entire stake in the lender by October.

Subhash Chandra

The rice trader-turned-media mogul, 69, who brought cable television into Indian homes in the early 1990s with his ZEE TV, resigned as chairman of Zee Entertainment Enterprises Ltd. in November and lost control of his crown jewel. To help pay the debt of Essel Group, Subhash Chandra has been selling stake in Zee Entertainment in the past few months to repay group’s debt.

Gautam Thapar

A default by Gautam Thapar, founder of the paper mill-to-power transmission Avantha Group, on pledged shares made Yes Bank Ltd the biggest shareholder in CG Power and Industrial Solutions Ltd. In August, the firm was hit by an accounting scandal forcing the board to remove Thapar, 59, from the chairman’s post. A month later, the market regulator ordered a forensic audit of the firm and barred Thapar from accessing securities market.