Heatwaves: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Heatwave: One word or two?

Oxford Dictionaries spell heatwave as one word, and provide this illustration:

‘when a heatwave occurs many people become increasingly bad-tempered’

In Australia, too, it is one word.

Among major dictionaries Cambridge English Dictionary, Collins English Dictionary and Macmillan Dictionary, too, spell heatwave as one word. Only Merriam-Webster spells it as two.

Definition

In large areas, a heat wave is declared when the maximum temperature is 45 degrees Celsius for two consecutive days and a severe heat wave is when the mercury touches the 47 degrees-mark for two days on the trot.

In small areas like Delhi, heat wave is declared if the temperature soars to 45 degrees Celsius even for a day, according to the India Meteorological Department (IMD).

Definition

The IMD defines a heatwave day when the maximum is 4.5°C or more above the normal temperature and the maximum is at least 40°C.

A heatwave is also declared if the maximum touches 45°C or above.

A ‘severe heatwave’ is declared when the maximum is 6.5°C or more above normal

Heatwaves are not a ‘notified disaster’ in India

Amitabh Sinha, June 13, 2024: The Indian Express

From: Amitabh Sinha, June 13, 2024: The Indian Express

The DM Act was enacted in the wake of the 1999 Odisha super-cyclone and the 2004 tsunami. It defines a disaster as a “catastrophe, mishap, calamity or grave occurrence” arising from “natural or man-made causes” that results in substantial loss of life, destruction of property, or damage to the environment.

The ongoing spell of extreme heat in many parts of the country has once again reopened discussions on the inclusion of heatwaves as one of the notified disasters under the Disaster Management (DM) Act, 2005.

If the inclusion does happen, states will be allowed to use their disaster response funds to provide compensation and relief, and carry out a range of other activities for managing the fallout of a heatwave. Currently, states need to use their own funds for these activities.

What are notified disasters?

The DM Act was enacted in the wake of the 1999 Odisha super-cyclone and the 2004 tsunami. It defines a disaster as a “catastrophe, mishap, calamity or grave occurrence” arising from “natural or man-made causes” that results in substantial loss of life, destruction of property, or damage to the environment. It must also be of such nature which is “beyond the coping capacity” of the community.

If such an event happens, then the provisions of the DM Act can be invoked. The provisions allow states to draw money from the two funds that have been set up under this law — the National Disaster Response Fund (NDRF) at the national level and the State Disaster Response Fund (SDRF) at the state level. The states first utilise the funds available in the SDRF, and only if the magnitude of the disaster is unmanageable with the SDRF, states seek the money from the NDRF. In the FY 2023-24, only two states drew money from the NDRF (see box).

While the entire money of the NDRF comes from the central government, states contribute 25% of the money in the SDRF (10% in case of special category states), the rest comes from the Centre. The money in these funds cannot be used for any purpose other than response and management of notified disasters.

Currently, there are 12 categories of disasters which are notified under this Act. These are cyclones, drought, earthquake, fire, flood, tsunami, hailstorm, landslide, avalanche, cloudburst, pest attack, and frost and cold waves.

Why heatwaves were not included as notified disasters?

Though heatwaves are not a new phenomenon in India, and heat-related illnesses and deaths have been common in large parts of northern, eastern and central India, these were not viewed as a disaster when the Act came into being in 2005. It was because heatwaves were a common occurrence during summer, and not really an unusual weather event.

In the last 15 years, however, both the severity and frequency of heatwaves have increased. Due to increased economic activity, there is a far larger number of people who have to remain outdoors for their livelihoods or other reasons, exposing them to the risk of a heat-stroke. There are 23 states, which are vulnerable to heatwaves.

These states as well as several vulnerable cities have now prepared heat action plans (HAPs) to deal with the impacts of extreme heat. HAPs involve activities like creation of shaded spaces, ensuring availability of cool water in public places, distribution of simple oral solutions, and reorganising the schedules of schools, colleges and office working hours.

These measures require expenditure but state governments have not been able to use the SDRF for them. This is the reason for the demand for inclusion of heatwaves as a notified disaster in the DM Act.

Why is the Centre not adding heatwaves as a notified disaster now?

There are primarily reasons for this:

1. Finance Commission Reluctance

States have put the demand of including heatwaves as a notified disaster before the last three Finance Commissions — the periodically established Constitutional body that decides on the distribution of financial resources between the Centre and states.

However, the Finance Commissions have not entirely been convinced. The 15th Finance Commission, whose recommendations are currently being applied, said the existing list of notified disasters “covers the needs of the states to a large extent” and did not find merit in the request to include heatwaves.

But it endorsed an enabling provision created by the preceding Commission that allowed states to utilise at least a part of the SDRF money — up to 10% — for “local disasters” such as lightning or heatwaves, which states could notify on their own.

Using this new enabling provision, at least four states — Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, Odisha, and Kerala — have added heatwaves as local disasters.

The Centre has so far resisted demands to notify it as a national disaster, using the Finance Commission as an excuse.

2. Practical Difficulties

Although unstated, the main reason behind the reluctance to add heatwave as a notified disaster is the potentially huge financial implication of the move. The government has to provide monetary compensation — Rs 4 lakh — for every life lost because of a disaster that is in the notified list. Grievous injuries also have to be compensated.

Heatwaves claim a large number of lives every year, even though the recorded number of deaths have not been very high in recent years. But this is changing. This year, more than 500 heat-related deaths have already been reported. Once the government is mandated to provide compensation, a larger number of deaths could be revealed.

The other reason is the problem in attributing deaths to heatwaves. In most cases, heat itself does not claim lives. Most people die due to other pre-existing conditions, made worse by the impact of extreme heat. It is often difficult to ascertain whether it was heat that made the difference. This is very different from other disasters in whose case the identification of the victims is easier and more straight-forward.

For the five year period between 2021-26, the 15th Finance Commission had recommended an allocation of Rs 1,60,153 crore to the various SDRFs, a substantial sum of money. A state like Uttar Pradesh has been allocated about Rs 11,400 crore in its SDRF for the five-year period. Maharashtra’s share is the maximum, about Rs 19,000 crore. This money is meant to deal with all kinds of disasters during this period. The fear is that even this money could become insufficient if heatwaves and lightning — another disaster that claims a large number of lives every year — is added to the notified list of disasters.

On the other hand, inclusion as a notified disaster can improve the management of heatwaves. Heat-related illnesses and deaths would be better reported, and authorities would be more alert to minimise the impacts of heatwaves.

The number of heatwave days in a year

1970- 2019: statewise

May 18, 2023: The Times of India

From: May 18, 2023: The Times of India

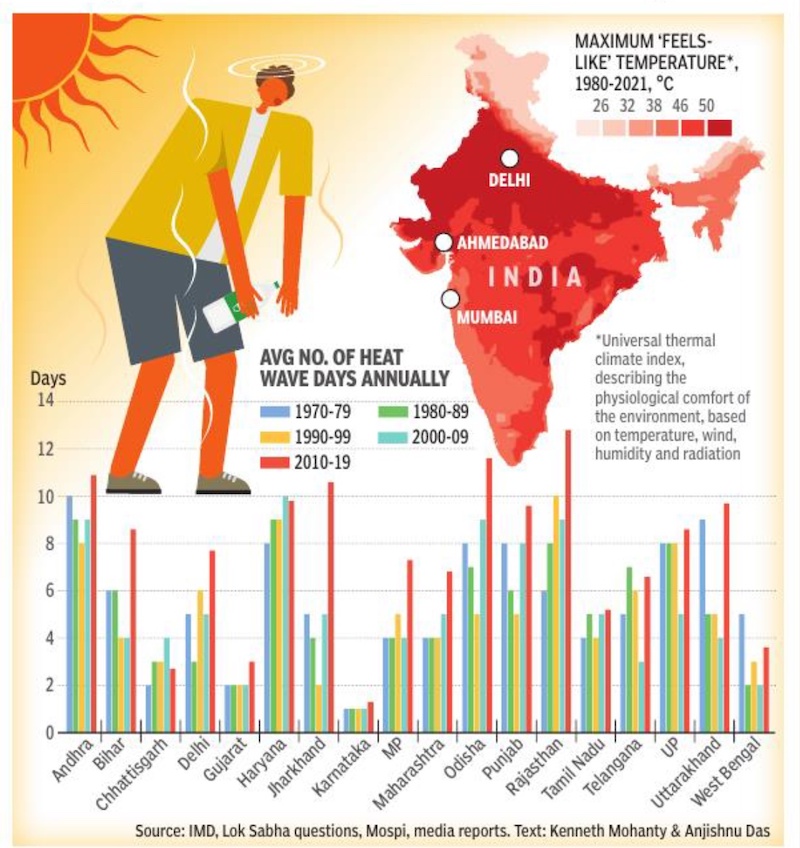

Since 1970, there have been only two years when the annual average exceeded 200 for the number of cumulative heatwave days and both have come within the last 15 years. There were 203 heatwave days in the country in 2022 – the figure represents the sum of average heatwave days recorded by the states – while 2010 had seen 256 such days, according to IMD.

The decadal average for total heatwave days zoomed to 130 for the 2010s, up by more than 35% over the previous high of 96 in the 1970s. Heatwave days in the first three years of the 2020s have already produced an yearly average of 93, the third highest since the 1970s.

Analysis of IMD data shows that compared with the previous decades, starting with the 1970s, the period 2010-2019 brought big jumps in annual average heatwave days for most states in the north-western, central and eastern and coastal regions of the country.

Withering Highs

Average temperatures over India increased by around 0. 7°C during 1901-2018 with sea-surface temperatures in the tropical Indian Ocean going up by 1°C for 1951-2015, the Centre says. The average annual frequency of warm days and nights in India has increased and of cold days and nights has decreased since 1951.

Already, 2022 was the fifth hottest year for India since 1901, when IMD started keeping records, and the outlook for El Nino weather conditions – linked with more intense heatwaves – poses worries for the country in 2023.

Maximum temperatures of at least 40°C or more for plains and 30°C or more for hilly regions are taken into account for declaring a heatwave. In coastal regions, a departure of 4. 5°C or more from normal can trigger an alert if the actual maximum is 37°C or more. But experts say humidity and radiation, etc. should also be factored in while estimating the severity of a heatwave. By that yardstick, The Economist magazine reports, there are parts of India where temperatures have routinely “felt like” 50°C or more in the last few decades (see map).

How Prepared Is India?

After 2030, 160-200 million Indians could be exposed to extreme heat every year, the World Bank says. An IIT-Gandhinagar study predictsthat severe heatwaves could be 30 times more frequent by 2100. If climate change continues unabated under the current policies, heatwaves could be 75 times more frequent by 2100.

A study by the Delhi-based Centre for Policy Research (CPR) found most Heat Action Plans (HAPs) – laying down guidelines for dealing with extreme heatevents – are insufficient. Analysing 37 HAPs across 18 states, CPR found that most plans do not account for local conditions and instead have an “oversimplified” approach that focuses only on extreme dry heat.

Only 10 of the 37 HAPs have temperature thresholds specific to their regions that account for localised factors, like humidity and hot nights, when declaring a heatwave. Almost every HAP fails to identify and target vulnerable populations, making it difficult to direct policy and resources towards those who need them the most. Moreover, HAPs are underfundedwith many requiring government agencies to self-allocate resources for the programme. The government estimates that between 1990 and 2020, nearly 26,000 people died due to heatwaves, though experts say the true toll is likely to be much higher. A 2022 report by medical journal The Lancet says India saw a 55% increase in extreme heat-related deaths between 2000-04 and 2017-21.

The Economic Cost Of Extreme Heat

In 2017, 50% of India’s GDP and 75% of its workforce relied on heat-exposed work. By 2030, though heat-exposed work will dip to 40% of the GDP, India will lose 2. 5-4. 5% of its GDP, or $150 billion to $250 billion, due to heat.

Extreme heat can be particularly devastating for agriculture. Heatwaves can damage crops, strain water resources, and lower the output of animal products like milk and meat. The Indian Institute of Horticulture said some regions could lose 10% to 30% of their fruit and vegetable crops due to heat this year.

Heatwaves will also likely strain the energy sector by increasing the demand for cooling. However, coal – which provides a big chunk of power in India and is one of the biggest sources of greenhouse gas emissions worldwide – stands to further exacerbate climate change induced extreme weather events.

2011-20; 21

From: Priyangi Agarwal & Jasjeev Gandhiok, July 10, 2021: The Times of India

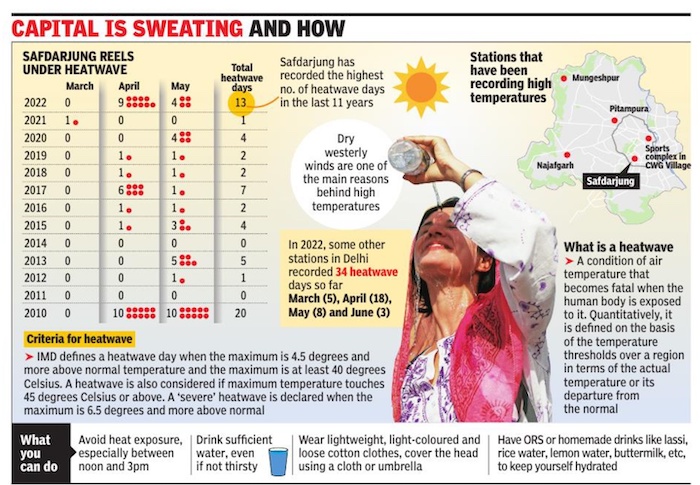

See graphic:

The total number of Heatwave days in the Delhi region, 2011-20; 21

2001-16

The Times of India, May 21 2016

Jayashree Nandi

Rajasthan's Phalodi recorded the country's highest temperature ever of 51°C. The India Meteorological Department has said the frequency of severe heatwaves had increased sharply in the past 15 years.

Most heat-affected states have no plan in place to prevent mortality and morbidity associated with extreme heat. IMD officials said the average frequency of severe heat waves had doubled from 50 days a year across India until 2000, to about 100 in the 2001-2010 decade. The figures are cumulative numbers from all IMD stations. So, if there are 10 severe heat wave days in two cities simultaneously, it's counted as 20.

“The frequency of both heatwaves and severe heatwaves has increased, particularly in the last two decades. The reasons could be related to climate change, urban heat island effect or others,“ said B P Yadav, director, National Weather Forecasting Centre at IMD.

He added that between 2010 and 2016 too, heatwaves showed an upward trend.IMD has started issuing a separate colour-coded heat wave forecasting from this year, which alerts agencies on when interventions are required, because of what it called a “visible increase“ in both mean temperature and heat wave incidents.

IMD's observations correlate with warnings by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) of a steady increase in warm days and nights globally, and higher temperatures in cities due to the urban heat island effect.

The Indian Institute of Public Health (IIPH), which has developed a heat action plan for Ahmedabad and helped cities in Maharashtra develop theirs, has advised the Union health ministry to ensure that similar plans are implemented in all states affected by heatwaves.

As of now Maharashtra, Gujarat, Telangana and Andhra Pradesh have started a heat action plan.

“Mortality increases as soon as there is a heatwave.For instance, on Thursday when it recorded 48 degrees in Ahmedabad, there were 130 deaths compared to 100 deaths daily on an average.During the 2010 heat wave, there were 310 deaths in a day and about 800 deaths in total in the following week,“ said Dr Dileep Mavalankar, director, IIPH, Gandhinagar.

“Since the frequency of heatwaves is increasing due to climate change, we have been pursuing the implementation of heat plans with the government. Ideally local government administration or municipalities should be in charge of it,“ Mavalankar said.

2011- 2021 June

Jasjeev Gandhiok & Priyangi Agarwal, June 17, 2021: The Times of India

From: Jasjeev Gandhiok & Priyangi Agarwal, June 17, 2021: The Times of India

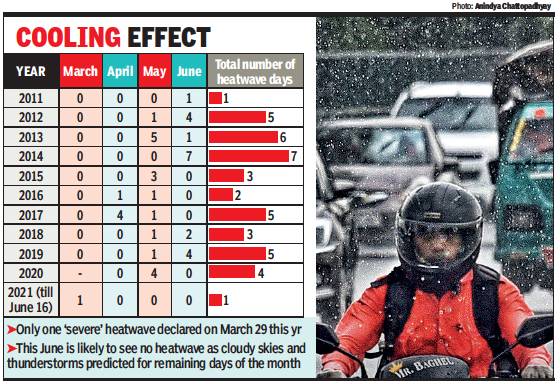

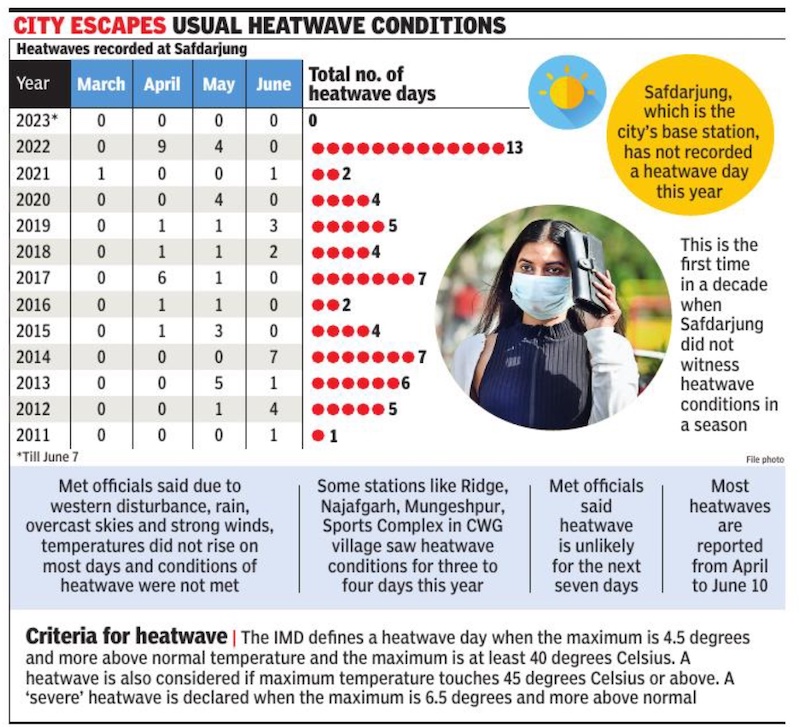

Delhi has had comparatively salubrious weather this year, with only a single heatwave day so far — the fewest since 2011 when one heatwave day was recorded between March and June. This year too, the only heatwave day recorded was on March 29. With the rainy season around the corner, meteorological officials say another heatwave day is unlikely now in 2021.

A heatwave, in India Meteorological Department definition, is when the maximum temperature is at least 40 degrees Celsius and 4.5 degrees or more higher than normal temperature or the maximum touches 45 degrees Celsius in a meteorological region. The data shows that March 29 recorded 40.1 degrees Celsius, eight degrees above normal. After IMD classified this as a ‘severe’ heatwave day, Delhi hasn’t logged another heatwave day since. In April, the highest maximum recorded was 42.2 degrees Celsius on April 28, four above normal. May was even cooler, with the highest touching just 41.6 degrees Celsius.

IMD data shows the mean maximum temperature for June is 37.5 degrees Celsius, two below the monthly normal of 39.5 degrees. So far, the warmest day has been 42.2 degrees Celsius on June 9. Earlier on May 19, under the influence of Cyclone Tauktae, the city recorded the highest ever single-day rainfall for the month of May. The impact of Cyclone Yaas then helped keep the mercury level from rising. Normal temperatures in May and June touch 43-44 degrees Celsius, with 45.6 degrees in 2019 being the maximum.

Last year, four heatwave days were recorded in Delhi, five in 2019, three in 2018, five in 2017 and two in 2016. The highest number of heatwave days recorded in Delhi in the last decade was seven in 2014.

Kuldeep Srivastava, scientist at IMD and head of the Regional Weather Forecasting Centre, said, “In Delhi, most of the heatwaves days occur in April, May and first week of June. However, not a single heatwave hit the city from April onwards this year because of a series of western disturbances and cloudiness. Also, the maximum temperature this year has not reached the peaks of earlier years.”

Srivastava added, “Delhi is now seeing pre-monsoon activities, including thunderstorms and cloudiness, and monsoon is imminent. It is, therefore, unlikely that there will be heatwave day in the second-half of June.”

IMD data analysed by the Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW) confirmed Delhi’s maximum temperature in May this year was the lowest in the last 70 years. "The summer of 2021 got rare relief from heatwaves because of over five western disturbances and cyclone Tauktae,” pointed out Abinash Mohanty, programme lead, CEEW. “Delhi recorded below normal maximum temperatures and increased wet spells, with more than 60mm of single-day rainfall during a spell. This, coupled with the string of western disturbances, hindered the rise of mercury in NCR. This will also influence the intensity and onset of the monsoon.”

2013-2024

From: March 28, 2025: The Times of India

See graphic:

2013-2024: Number of heat waves recorded at Delhi’s base Station

2017

India Today , The heat is on “India Today” 11/9/2017

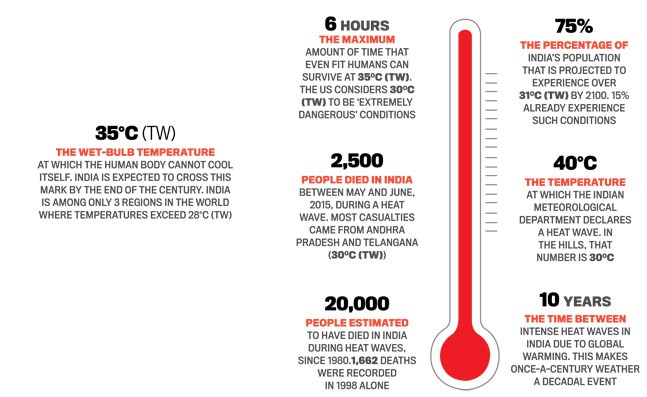

A study published this month in Science Advances, an American journal, shows that by the end of the century large parts of India may become uninhabitable due to a combination of heat and humidity. The study examined data based on rising wet-bulb temperatures (TW), a measure of the air temperature combined with humidity, to account for relatively cool days that feel hotter because of high humidity. Once a certain wet-bulb temperature is exceeded, the body can no longer cool itself. According to the study, at these temperatures, "exposure, for even a few hours will result in death even for the fittest of humans under shaded, well-ventilated conditions".

2021: unusual pattern

Priyangi Agarwal & Jasjeev Gandhiok, July 10, 2021: The Times of India

Heatwave conditions usually abate in the Delhi region by mid-June. This year, however, there were seven heatwave days in the latter part of June and early July, when usually there is pre-monsoon weather activity. The city did not record a single heatwave day in April and May and just one in Marchend. But the eight heatwave days recorded this year are the highest in the last seven years. Experts attribute the heatwave to lack of rain in June and July.

India Meteorological Department defines a heatwave day as one with when the maximum temperature is 4.5 degrees above the normal and the maximum is at least 40 degrees Celsius. A heatwave also occurs when the maximum temperature touches 45 degrees Celsius. A severe heatwave is declared when the maximum is 6.5 degrees and more above normal.

In Delhi, most of the heatwave days occur in April, May and the first week of June. However, this year not a single heatwave day was recorded between April and the first half of June. A severe heatwave day swept the capital all the way back in March, again unusual for that time of the year.

“A series of western disturbances and two cyclonic storms — Cyclone Tauktae and Cyclone Yaas — helped keep the mercury in check,” said a Met official. “Under the influence of Cyclone Tauktae, the city also recorded the highest single-day ever rainfall in May. Delhi saw thunderstorms and cloudiness on most days from April to mid-June and the temperatures mostly remained below the normal-mark.”

In July, the capital has recorded five heatwave days so far, the most in nine years, just short of the seven in July 2012. As IMD’s forecast says the onset of monsoon over Delhi is likely to happen soon, another heatwave is unlikely this year.

Abinash Mohanty, programme lead, Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW), says the 2021 summer will be seen as one of anomalies, characterised by consecutive heatwave days and increased wetbulb temperatures at June-end and early July. Mohanty explained, “The delayed onset of monsoon due to a complex interaction of westerly winds with moisture carrying easterly winds impacting the weather patterns and micro-climate. Globally, the rise in wet-bulb temperatures has led to mass mortality and can have severe repercussions on human health and productivity, industrial revenue and agricultural productivity.”

R.K Jenamani, scientist at IMD, said several western disturbances in April and May did not allow temperatures to rise significantly. “Generally, one gets 3-5 western disturbances in a month, but April and May saw even up to 11 in a month, which brought regular rainfall over the northern plains. Due to this, the maximum temperature hardly crossed 42 degrees Celsius,” said Jenamani, adding that even when the monsoon arrives at Juneend, it is generally weak and heatwave days in late June or early July aren’t so uncommon.

2022, till mid-June

Delhi: Heatwave days, , till mid-June

Priyangi Agarwal, June 14, 2022: The Times of India

From: Priyangi Agarwal, June 14, 2022: The Times of India

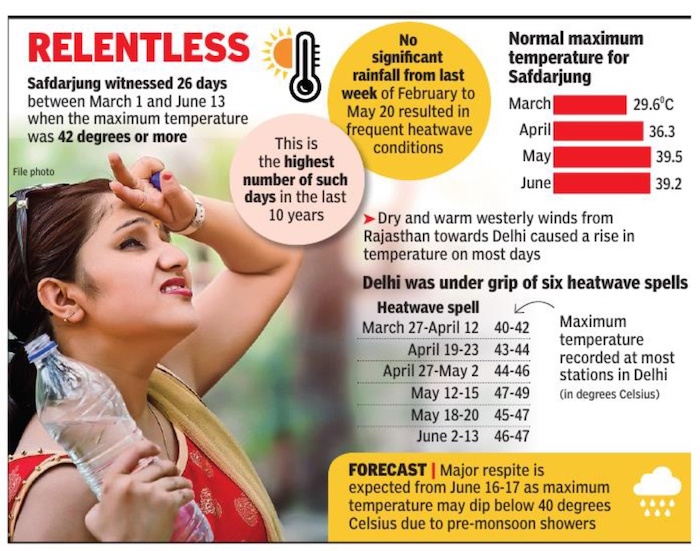

New Delhi: Safdarjung witnessed 26 days when the maximum temperature was 42 degrees or more between March 1 and June 13. This is the highest number of such days in the past 10 years. Safdarjung, the city’s base weather station, saw 30 such days in 2012.

According to India Meteorological Department, the normal temperature for March, April, May and June for Safdarjung is 29. 6, 36. 3, 39. 5 and 39. 2 degrees Celsius, respectively. An official said a temperature of above 40 degrees Celsius raises discomfort.

Data from the Met department shows that just six and three such days were recorded in 2021 and 2020, respectively, between March 1 and June 30 when the maximum temperature was 42 degrees Celsius and above. No such day was reported in 1953, 1954 and 1971. IMD said the summer of 2010 saw the highest number of such days (35).

The capital recorded six spells of heatwave this year. RK Jenamani, senior scientist, IMD, said, “Summer 2022 in northwest India, including Delhi, uniquely started and progressed. As no significant rain was recorded from the last week of February till May 20, it led to dry conditions, resulting in frequent days with high temperature. ”

“Two active western distur- bances hit north India from May 22 to 30, giving respite from heatwave conditions. Rain helped surpass the normal mark of rainfall for the entire month of May. However, dry spell has again continued from June 1. The maximum temperature at Safdarjung has been above 42 degrees Celsius since June 3. The prolonged heatwave has affected people, plants and animals,” added Jenamani.

A major respite from heatwave conditions is expected on June 16-17. “The ongoing heatwave spell, which began from June 2, may be the last major one of this season. From June 16, heatwave is predicted to abate from northwest and central India, including Delhi-NCR. Pre-monsoon showers are expected from this week, which may bring down the temperature to below 40 degrees Celsius by June 16-17,” Jenamani said.

IMD has forecast the maximum temperature to be around 39 degrees Celsius on June 17, which may come down to 36 degrees Celsius on June 19. The maximum and minimum temperatures on Monday at Safdarjung was reported at 43. 7 and 31. 6 degrees Celsius, respectively. Both temperatures were four degrees above normal.

Till late July

Vishwa Mohan, July 28, 2022: The Times of India

From: Vishwa Mohan, July 28, 2022: The Times of India

New Delhi: India reported one of its hottest summers in 2022 recording 203 heatwave days, which was the highest in the recent past. The maximum number of such episodes this year were reported from Uttarakhand (28), followed by Rajasthan (26), Punjab and Haryana (24 each), Jharkhand (18) and Delhi (17). The figure of 203 was arrived at after adding the average number of heatwaves that scorched states during the summer. Data on average number of heatwave episodes in states, shared by the ministry of earth sciences in LS shows the total number of heatwave days in the country this year was over five times more than such episodes (36) in 2021 with Punjab and Haryana reporting 12 times more number of heatwave days in 2022 compared to last year when these two states recorded only two heatwave days each. Data shows Assam, Himachal and Karnataka have not reported any heatwave day at all this year.

Region-wise

Delhi

The city recorded heatwaves in July in 2014, 2021.

Four heatwaves swept Delhi in a single year in 2014.

General

Most heatwave days occur between April 16 and May 31

2010- May 2022

June 7, 2022: The Times of India

From: Priyangi Agarwal, June 7, 2022: The Times of India

New Delhi : This summer, Delhiites experienced the highest number of heatwave days in 12 years. While the city’s main weather station, Safdarjung, has recorded 13 heatwave days so far, some stations have logged as many as 34 since March, as per IMD, reports Priyangi Agarwal.

The last time Safdarjung recorded a higher number of heatwave days during the same period was 20 in 2010. The stations that have reported 34 such days till June 6 are all new installations for which historical data is not available. Of these 34 days, these stations recorded heatwave conditions on five days in March, 18 days in April, eight days in May and three days in June so far.

2011- May 23

From: Priyangi Agarwal, June 8, 2023: The Times of India

See graphic:

Heatwaves recorded at Safdarjung, 2011-23, March, April, May, June

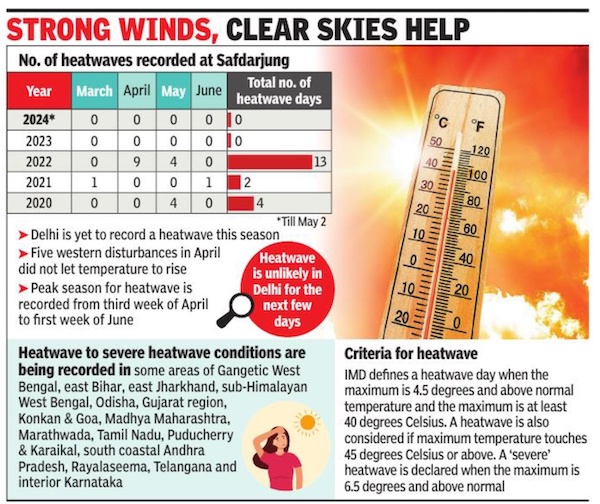

2020-2024 Apr

From: Priyangi Agarwal, May 3, 2024: The Times of India

See graphic:

Heatwaves in Delhi, 2010- Apr 2024

2011-2025: March to June

From: Priyangi Agarwal, June 21, 2025: The Times of India

See graphic:

Heatwaves recorded at Safdarjung, Delhi, 2011-25, March, April, May, June

Deaths caused

2000-21

Vishwa Mohan, Oct 26, 2022: The Times of India

From: Vishwa Mohan, Oct 26, 2022: The Times of India

NEW DELHI: The number of heat-related deaths in India among those over 65 years increased 55% from an average of about 20,000 deaths per year during 2000-04 to around 31,000 fatalities annually during 2017-21, and the period suitable for dengue transmission has gone up to 5.6 months each year from 1951-60 to 2012-21, says the latest Lancet Countdown report on the worsening global impacts of climate crisis on human health.

The report noted that globally such heat-related deaths had increased 68% during 2017-21, reaching 3,10,000 deaths annually. It said the death toll was significantly exacerbated by the confluence of the Covid-19 pandemic.

The report also underlined how the governments’ support to fossil fuel consumption through subsidies in many countries is creating problems globally and has led to deterioration of air quality, decline in food output and increasing risk of infectious disease linked to higher carbon emission.

The report flagged that over 3,30,000 people died in India in 2020 due to exposure to fossil fuel pollutants.

“The climate crisis is killing us. It is undermining not just the health of our planet, but the health of people everywhere — through toxic air pollution, diminishing food security, higher risks of infectious disease outbreaks, record extreme heat, drought, floods and more,” said UN secretary-general Antonio Guterres while reacting on the findings of the report.

2010-18

Heat waves killed over 6k since 2010, January 3, 2018: The Times of India

Over 6,100 people have died in India due to heat wave in the last nine years (2010-18) with the year 2015 alone recording nearly one-third such deaths. Among states, Andhra Pradesh had recorded the maximum casualties during 2013-15 period.

Analysis of the casualty figures shows that Andhra Pradesh, Telangana (after its formation in June, 2014), Odisha and West Bengal had together reported over 90% of total deaths due to heat wave during the period.

Sharing the nationwide cumulative figures in Lok Sabha, minister of earth sciences Harsh Vardhan on Wednesday said a latest study had showed that heat waves have increased in many parts of the country with these conditions being experienced generally during the period between March and July.

He, however, said the India Meteorological Department in collaboration with state health departments have started a heat action plan in many parts of the country as “an adaptive measure” to forewarn about heat waves and advise on preventive action to be taken. Figures show that 2,081 people had died due to heat wave in 2015.

2013-16

The Times of India, April 27, 2016

87 deaths take heatwave toll since 2013 to 4,204

As many as 87 people died between January and March 2016 owing to a heatwave, with the first three months of 2016 experiencing significantly abovenormal temperatures.

At 56, Telangana recorded the maximum casualties, followed by Odisha (19).Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka and Kerala witnessed one heatwave casualty each.

The deaths in 2013 take India's heatwave toll since 2013 to a staggering 4,204. In 2013, 2014 and 2015, heatwave killed 1,433, 549, and 2,135 peo ple, respectively. The figures were shared by earth sciences minister Y S Chowdary in the Lok Sabha on Wednesday in a written response to a question asked by over nine parliamentarians.

The number may go much higher if states do not take adequate precautionary me asures, as advised by IMD, in view of a forecast of higherthan-average temperatures for this year's summer (April-June). “Above normal heatwave conditions are very likely over central and north-west India during the 2016 hot weather season,“ Chowdary said.

2018

Sushmi Dey, ’31k heat-related deaths of 65+ in India in 2018’, December 3, 2020: The Times of India

India reported over 31,000 heat-related deaths of people older than 65 years in 2018, the second highest in the world after China (62,000), a new Lancet Countdown report on health and climate change shows, reports Sushmi Dey.

While heat-related mortality among people above 65 has increased by 53.7% globally during the past 20 years, it more than doubled in India. Globally, 2,96,000 deaths among the age group were reported in 2018.

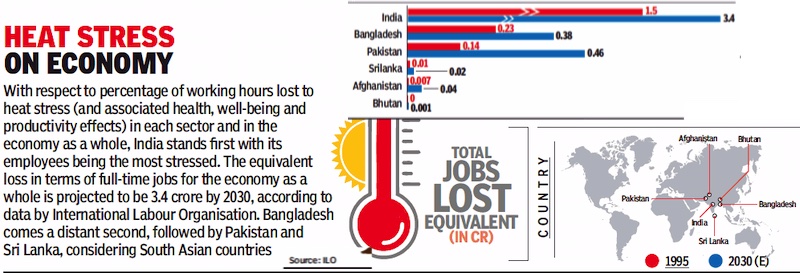

The report shows India accounted for highest productivity loss at 40% of the total 302 billion work hours lost during 2019.

India’s agriculture sector among worst-affected by heat: Report

The report underlines that livelihoods are at risk because heat is increasingly affecting people’s ability to work outdoors in developing regions with significant economic implications. “India and Indonesia were among the worst affected countries, seeing losses of potential labour capacity equivalent to 4-6% of their annual gross domestic product,” it says. The report highlights that India’s agriculture sector was among the worst affected.

“The pandemic has shown us that when health is threatened on a global scale, our economies and ways of life can come to a standstill,” Dr Ian Hamilton, executive director of Lancet Countdown, said. “The threats to human health are multiplying and intensifying due to climate change and unless we change course, our healthcare systems are at risk of being overwhelmed in the future.”

In 2019, India saw a record number of above-baseline days of heatwave exposure affecting people aged over 65. Eight of the 10 highest ranking years of heatwave exposure in India have occurred since 2010. “The changing climate has downstream effects, impacting broader environmental systems, which in turn harm human health,” says the report.

Impact on health

2012-16: 40m additional Indians affected

‘Heatwaves hit 40m more Indians in 5 yrs’, November 29, 2018: The Times of India

Climate change is hitting home. India saw an increase of 40 million in the number of people exposed to heatwaves from 2012 to 2016 (counting both years), a global report prepared by 27 leading academic institutions, the United Nations and inter-governmental agencies has said.

The surge in heatwaves in India posed a major danger to health and called for urgent action to develop and implement local heat action plans, according to the study.

The Lancet Countdown report on health and climate change, released on Wednesday, said average temperatures in India are projected to rise alarmingly. Between 1901 and 2007, India’s mean temperature rose by more than 0.5 degree Celsius. “While the world is bracing for an increase of around 2 degrees C over the 21st century, northern, central and western India may witness increases averaging 2.2 to 5.5 degrees by the end of the 21st century,” it said.

Heatwaves tied to exacerbation of heart failure, kidney injury

Globally, the Lancet report said, vulnerability to extremes of heat has steadily risen since 1990 in every region, with 157 million more people exposed to heatwaves in 2017 as compared to 2000.

The average person experienced an additional 1.4 days of heatwaves per year over the same period, it said. Low- and middleincome countries, India included, are likely to be worst affected by climate change, given weaker health systems and poorer infrastructure, experts said.

Heatwaves are associated with increased rates of heat stress and heat stroke, exacerbation of heart failure and acute kidney injury from dehydration. Children, the elderly and those with pre-existing morbidities are particularly vulnerable.

Dr K Srinath Reddy, an author of the India policy brief of the Lancet report, said identifying local heat hot spots through appropriate tracking and modelling of meteorological data is needed tackle the crisis.

“Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation has adopted a heat action plan, which necessitates measures such as building heat shelters, ensuring availability of water and removing neonatal ICU from the top floor of hospitals. It has helped bring down the impact of heatwave of vulnerable population. Similar action plan should be developed by other states also,” said Dr Reddy, who is also head of the Public Health Foundation of India.

The Lancet report shows 153 billion hours of labour were lost globally in 2017 due to heat, an increase of 62 billion hours relative to year 2000. The impacts, the authors on India policy brief note, vary with different sectors with the agriculture being most vulnerable as compared to the industrial and services sector.

“For India, whose large agriculture economy makes up 18% of the country’s GDP and employs nearly half the population, this translates into substantial climate-related impacts on the workforce and economy,” said Dr Reddy.

Overall, India lost nearly 75,000 million hours of labour in 2017, relative to about 43,000 million hours in 2000, an increase of over 30,000 million hours over two decades. “For a developing economy like India, this represents a substantial impact on individual, household and national budgets, necessitating urgent national and regional adaptation plans,” the report said.

Impact of heat on productivity

1995

From: July 5, 2019: The Times of India

See graphic, ' The impact of heat on productivity in Afghanistan, Bhutan, Bangladesh, India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka/ 1995 '

See also

January weather in India <> February weather in India <> March weather in India <> April weather in India <> May weather in India <> June weather in India <> Summers: India<> Heatwaves: India <>July weather in India <> August weather in India <> September weather in India <> Monsoons: India<> October weather in India <> November weather in India <> December weather in India <> Winter rains: India <> Winters: India <> Heatwaves: India